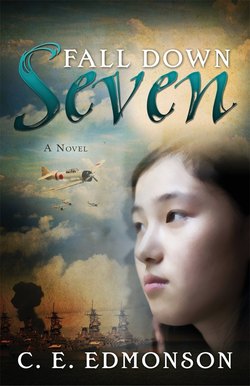

Читать книгу Fall Down Seven - C. E. Edmonson - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеIt didn’t take more than two seconds for me to realize I’d been completely naïve. Somehow, probably because I was desperate at the time, I had imagined the train being a place of refuge, a sanctuary. But the long passenger car we entered was really a trap. Our original strategy—keep moving—wouldn’t work there because there was no place to go. Oh, sure, we could change cars, but the second-class cars were all the same: long and narrow, with a row of dome lights running along the center, and luggage racks on either side. The people were all the same too. They regarded us with suspicious eyes as we stood on the platform with Officer Mackley. As we boarded the train clutching our suitcases, we were again on our own.

We made our way along the aisle to a pair of facing seats. Then Mom and I put the suitcases on the racks and we settled down, me and Charlie on one seat, facing backward, Mom on the other.

I stared at her for a moment. She wore a yellow scarf on her head, the scarf wet enough to appear almost transparent. I knew I didn’t look any better. My hair was a shade lighter than Mom’s jet black, and I could feel it clinging to my neck. I kept my hair fairly short, and I didn’t curl it into flowing waves—the style in the early 1940s. Now it lay plastered against my scalp like paint on the head of a doll.

I watched the Whizz look out through the window when the train began to move. Though he was as bedraggled as his mother and sister, he seemed unaware of his surroundings. Maybe he was still hoping our voyage would turn out to be an adventure.

The Whizz, like Dad, had always been an optimist. He looked more like Dad too. His hair was lighter than mine, and he even had a few freckles on either side of his nose. In Hawaii our mixed heritage had earned the Whizz and I the label of hapa, the Hawaiian word for half, or hapa haole, the Hawaiian term for half white. But here we were all Japanese. Observation wasn’t the Whizz’s strong point. He didn’t notice, for example, that the seats in front and behind us were empty, as were the seats to either side, even though the car was fairly crowded.

It felt to me at that moment like we’d been dropped into a pit. The glances we received—and everyone looked at us—were distinctly hostile. But nobody said anything, not just then.

The conductor came down and took our tickets a few minutes after we departed. He’d greeted each of his passengers along the way, but not us. After he moved on, the Whizz and I shrugged out of our wet jackets and laid them across the seat next to Mom. Then I somehow found the courage to fetch one of the suitcases from the rack, the largest one. I dug out a sweater for myself and another for Charlie. Mom looked at me and gave a slight shake of her head. She would endure.

I felt myself grow angry. At the end of the car, four soldiers lounged in seats across from each other. They were looking directly at us, their expressions a mix of hostility and contempt. I wanted to ask them why they were headed east, away from the fighting, while my dad’s ship roamed the Pacific in search of the enemy. The words were on the tip of my tongue, but my courage failed me at the last minute, and I sat.

“Here,” I said to Charlie, “put this on.”

A few minutes later, with the train entering the steep hills separating San Francisco from California’s central valley, a porter came down the aisle pushing a cart loaded with snacks. He wore a starched, snow-white jacket and a white cap with a stiff, black peak. He was short and thin, and the expression on his mahogany face was so unchanging it might have been set in stone.

The Whizz’s eyes fastened on a row of candy bars and didn’t move. Oh Henry!, Zagnut, Almond Joy, and Chuckles, arranged in little boxes. To say my younger brother had a pronounced sweet tooth would be to understate the reality by a mile. He sighed when Mom bought three hard-boiled eggs, three oranges, and a bottle of milk, but he didn’t argue. For once.

Mom bought a newspaper, too—the San Francisco Chronicle. Before Pearl Harbor, Charlie and I had paid no attention to the news. That was for grown-ups. I read the Sunday comic strips to my little brother and that was the end of it. Now, with Dad at sea, we followed the progress of the war as if knowing could somehow change the course of events—which needed changing because every day seemed to bring another Japanese victory. Hong Kong, Guam, Wake Island, Burma, the Dutch East Indies. We’d taken a stand in Singapore only to be brushed aside in a few days.

The headline across the top of the Chronicle’s front page on that day read: JAPS ADVANCE ON CORREGIDOR. A smaller article on the left side of the paper carried a familiar headline: “Japanese Atrocities in Bataan Verified!”

Mom glanced at the Chronicle and then turned it over to me. The Whizz, as usual, scooted across the seat to read over my shoulder. Only in second grade, he had to ask the meaning of every other word, and I sometimes became impatient. Not on that day, however. I wanted to keep my head down, to become so engrossed in the articles that I didn’t notice the four soldiers only a few rows away, or hear their comments about Japanese, or see them open a bottle that could only contain hard liquor and pass it around.

I started with the main article, the one I knew would affect our lives in Connecticut. Corregidor is a small island at the entrance to Manila Bay, on the southern end of the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Manila, the Philippine capital, had already been captured, and the American forces were making a last stand on Corregidor. Talk about a hopeless situation. The American commander, General Douglas MacArthur, had already been evacuated to Australia. But hopeless or not, Corregidor would play a central part in our immediate future.

Our final destination was the home of Ellen Hardy, Dad’s sister. Aunt Ellen didn’t have any children, but she did have a husband. Having graduated from West Point, Colonel Blake Hardy had been serving his country for twenty years. At the time he was in the Philippines, on the island of Luzon, fighting for his life.

Except for official messages transmitted in code, all communication with the American soldiers stationed on Luzon had been terminated a month earlier. Six weeks had passed without Aunt Ellen receiving a letter from her husband.

I knew all this because Mom had summoned me and the Whizz into our living room, which we rarely used, right before we had packed for the trip. She’d seated us on the couch, pulled a chair to within a few feet, sat, and folded her hands over her knees. We were accustomed to this ritual when Mom had something important to say. Our job was to listen attentively—even the Whizz, who couldn’t sit still for more than a few seconds.

“I want you to respect your aunt’s circumstances,” Mom had said after she’d explained the situation. “We must show her respect.”

As the Whizz and I understood Mom’s definition, respect meant keeping the noise down, no running through the house, picking up our clothes, and studying hard in school. This was a song we’d heard before, but then she had added, “We’re to be guests in someone else’s home.”

You couldn’t question Mom, and I didn’t. But I went to sleep that night thinking about the word “guest.” Guests were invited, right? And they could be asked to leave if they overstayed their welcome. Right? Suppose Aunt Ellen didn’t like us? Suppose she kicked us out? Where would we go? Back to Hawaii? We’d been authorized to travel from San Francisco to Connecticut, but there wasn’t a single word in the letter signed by Admiral Nimitz authorizing our return.

As the Whizz slowly read the article on Corregidor, I looked through the window at a landscape of fields that stretched to the horizon. The sky above was as blue as the skies in San Francisco were gray, the weather having cleared as we passed the steep hills east of the city. The fields were still brown this early in the spring, but the planting was underway. I watched a tractor move across a field. As it turned the earth, it threw up a great cloud of dust that hung motionless in the still air. A flock of crows trailed behind, fluttering down in twos and threes to feed on the suddenly exposed insects. This looked like a feast they enjoyed every spring.

The news from Corregidor hadn’t surprised me, simply because it was the same as the news on the previous day and the day before that. The fortifications were being continually bombed from the air and shelled by artillery. Food was in short supply. The garrison would not be—could not be—reinforced. The troops could surrender of course, but the allied soldiers who had surrendered at Bataan, according to the other story in the Chronicle, had either been massacred or were being worked to death as slave laborers. By the Japanese, of course.

The saddest part was that I had no reason to doubt the facts of the story. Japan had invaded China in 1931, a decade before Pearl Harbor, and advanced over time to occupy most of the country. The atrocities their armies heaped on defenseless Chinese citizens had been reported on for years.

The soldiers on the train grew rowdier as the bottle went around for the second time. Their tones sharpened, and the word “Jap” echoed through the narrow car. They laughed a lot too—hard laughter, the laughter of bullies who knew their victims couldn’t fight back.

Across from me, to my great relief, Mom began to straighten as though she’d made a decision—the only decision available. Her head came up, and she leaned toward us.

“These are bad men,” she told us. “You mustn’t listen to them.”

A good idea, but really hard to do because they were determined to disturb us. That was their goal. At one point they began to sing a popular tune, “It’s Taps for the Japs,” at the top of their lungs. A few minutes later, the conductor made his way up the aisle. He looked at the bottle, then from man to man.

“You need to calm down. You’re disturbing the other passengers.”

“The Japanese disturbed us pretty good at Pearl Harbor,” the loudest of the soldiers declared.

“You know where we’re going?” another soldier asked. “We’re headed to Fort Benning in Georgia for special training. Then it’s off to Germany.”

The conductor looked directly at us. An older man, his papery-white skin fell in soft folds along the sides of his neck. He didn’t seem any happier to be in our presence than the soldiers did, as if he’d been somehow soiled by our very existence. Nevertheless, he had a job to do.

“Fellas,” he finally said, “I don’t want no trouble on this train. If I get another complaint, the sheriff’s gonna be waiting at the station when we reach Sacramento.”

The soldiers did calm down a bit after that. Better still, they got off at Sacramento an hour later. I was hoping we’d seen the last of them, but they came back ten minutes later, and they had another bottle with them. Miraculously, they became more somber as they drank. Sooner or later they’d be off to fight, and they knew it.

Two hours later we stopped at a small town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Most of the passengers had left the train in Sacramento. The rest, including the soldiers, were asleep. I was trying my best to join them, only my eyes wouldn’t stay closed. I knew the soldiers would still be there when I woke up. I knew the next day would be a repeat of this one. Helpless is one of the worst feelings in the world, but that’s exactly how I felt. I couldn’t disguise myself, nor could I become invisible. People would see and judge me without my ever speaking a word. And there was nothing I could do about it.

Suddenly, the door at the far end of the car opened and a man entered, then closed the door behind him. He began to walk up the aisle toward us.

I shook Mom awake. “Someone’s coming.”

Mom turned to look then said, “It’s the porter.”

Only then did I recognize the man who’d pushed the snacks cart along the aisle after we’d boarded the train in San Francisco. He walked straight up to us and took our luggage down from the rack.

“Come with me,” he said.

Charlie woke up at that moment. “What? What?”

I felt like screaming out loud. Hadn’t we been put through enough? Now we were about to be evicted, dumped on a train platform in some town in the middle of nowhere. And with no explanation either. The porter simply marched off, our bags in hand, leaving us no choice except to follow.

We trailed behind like whipped puppies, but not to the platform. The porter led us to the car from which he’d come—a first-class car. He opened the door to a private compartment and put our bags on the luggage rack. Several blankets lay on the seats. A plate of sandwiches rested on a small, fold-out table.

“Y’all be more comfortable here, I believe,” he said.

The oddest part was that his grave expression didn’t change. The man’s full lips might have been molded from clay, and his firm jaw remained steady. His dark eyes stared straight ahead.

“Holy cow,” the Whizz said. “This is great.”

Mom had other ideas. “I’m so sorry,” she said with a little head bob. “We don’t have first-class tickets.”

“Don’t you worry. This time of year, the line runs pretty quiet. Ain’t but one compartment in use.” Then he smiled for the first time, a broad, mischievous grin that might have come from the Whizz. “Be right amusin’ tomorrow morning when them soldiers wake up to find you among the missin’.”

“What about the conductor?”

“Ol’ Simon? Bein’ as he’s already on probation for drinkin’ on the job, I don’t ’spect he’ll make no trouble. Fact, right now as we speak, Simon’s in the first-class compartment behind us, drainin’ a bottle of gin.”

“What’s your name?” I asked as he retreated to the door and the train pulled out of the station.

“Amos,” he said, tipping his hat. “Enjoy your trip on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Satisfaction guaranteed.”

Charlie was at the sandwiches before the door closed. I can’t say I was far behind. Even Mom ate. Afterward, I wanted to ask her why Amos had helped us, but I thought I knew the answer. That sign in San Francisco—the one about this being a white man’s neighborhood—excluded Amos and his fellow porters too.

What really mattered was my relief. I felt like I could breathe again. I felt as if I might float off the seat and hang in the air. Mom too. I could see it in her eyes. I wasn’t surprised when her practical side re-emerged. After we finished eating, she locked the compartment door, kissed each of us, and turned out the light.

The Whizz and I knew what she expected, but we didn’t go to sleep right away.

“Hey, look,” the Whizz said. “Snow!”

We’d been climbing the Sierra Nevada mountains since we’d left the station, and our view over a deep valley was as beautiful as it was foreign. A nearly full moon at the top of the sky bathed the cold, white peaks in the distance with a light so pure it took my breath away. Black in the moonlight, the pine trees in the valley huddled together as if defending against the cold, while clusters of stars framed the jagged peaks like diamonds in a royal tiara. At the far end of the valley, a light burned in the window of a house half buried in the snow.

“I bet it’s cold out there,” the Whizz said.

“Yeah, Whizz, it’s definitely cold.”

“Freezing cold?” When I didn’t answer, he said, “I bet nothing can live up there.” He pointed at a distant, snow-covered peak.

“What about the ghosts?” I asked.

“Ghosts?”

Mom spoke up then. “The ones that will get you if you don’t go to sleep.”

The Whizz took the hint. He drew a blanket to his throat and stretched out beside me. A few minutes later, he was asleep. For me, sleep was a long time coming. I couldn’t take my eyes off the vista outside our window. Every piece of it was foreign. The peaks of the Koolau Mountains on Oahu are covered with rain forest, not ice and snow, and they’re a full-time home to hundreds of species of birds. A thousand unnamed streams spill over cliffs to fall hundreds of feet to canopied pools choked with fish.

You’re not going back, I told myself. You can only go forward.

Forward toward what? I was thirteen years old. Growing up was challenge enough. Dad had instructed me to be strong. Fall down seven times, get up eight. Only there’s a difference between falling down and being knocked down.

“Emiko.” Mom reached her hand out to take mine. “Come, sit by me.”

Five minutes later I was asleep.