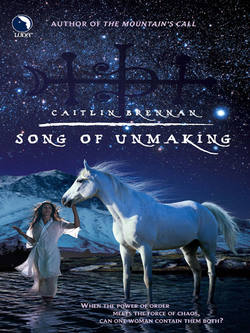

Читать книгу Song Of Unmaking - Caitlin Brennan - Страница 13

Seven

ОглавлениеKerrec lay motionless. Valeria was at last and mercifully asleep.

Her dream brushed the edges of his awareness. It was a dim thing, tinged with unease, but the white power of the stallions surrounded it. They guarded her even in dreams.

She could never know how much he wanted to turn and take her in his arms and kiss her until she was dizzy. But if he did that, he would have to open himself to her, and she would know.

She could not know. No one could. They had to believe that he was whole. He had to be. He could not afford to be broken.

During the day he could hold himself together. Much of what he did required no magic, or could be done with what little he had. He could still ride—that much had not left him. He could teach others to ride, and through the movements see the patterns that shaped the world.

The nights were another matter. He had to sleep, but in sleep were dreams.

At first he had been able to keep them at bay, even change them. His stallion had helped him. As winter went on, the dreams had grown worse.

Now he did not even need to sleep to hear that voice whispering and whispering, or to see the featureless mask of a Brother of Pain. Sometimes there was a stranger’s face behind it. More often there was one he knew all too well.

He never dreamed, awake or asleep, of the body’s pain. That had been terrible enough when it happened, and the scars would be with him until he died, but it was not his body that the Brother of Pain had set out to break. He had been commanded to break Kerrec’s mind and destroy his soul.

He had had to leave the task unfinished, but by then it was too far along to stop. What had been carried out of that place which Kerrec still could barely remember, had been the shattered remnants of a man.

The shards had begun to mend themselves. Kerrec’s magic had grown again, slowly but surely. He had dared to hope that he would get his old self back.

Then the healing had stopped and the edges of his spirit had begun to unravel. It was as if the Brother of Pain had reached out from the other side of the dream world and set his hooks in Kerrec’s soul again, even deeper than before.

Every night now, the whisper was louder, echoing inside his skull. What use is a dead prince in a living world? What purpose is there in this magic that you pride yourself in? What is order, discipline, art and mastery, but empty show? The world is no better for it. Too often it is worse. Give it up. Let it go. Set yourself free.

Every night he struggled to remember what he had been before. He had been a master of his art, endowed with magic of great power and beauty. His discipline had been impeccable. He had mastered the world’s patterns and could bend them to his will.

That was gone. The whole glorious edifice had fallen into ruin. All that was left was a confusion of shards, grinding on one another like shattered bone.

Very carefully he eased out of Valeria’s arms. It hurt to leave her—but it hurt more to stay. She was everything that he had been and more.

It was not envy that he felt. It was grief. He should have been her match, not a broken thing that she could only pity.

He was unprepared for the wave of sheer, raw rage that surged through him. The rage had a source—a name.

Gothard.

He could name the red blackness that laired in the pit of his stomach, too. It was hate. Gothard had done this to him. Gothard had given the Brother of Pain his orders. Gothard’s malice and spite had broken Kerrec’s mind and shattered his magic.

Gothard his brother, Gothard the half-blood, had nothing but loathing for his brother and sister who were legitimate as he was not, and for his father who had sired him on a hostage. He wanted them all dead—and he had come damnably close to succeeding.

He had escaped defeat and fled from the reckoning. No one, even mages, had been able to find him. But Kerrec knew where he was. He was in Kerrec’s mind, taking it apart fragment by fragment.

Somewhere, in the flesh, he was waiting. Kerrec had no doubt that he was preparing a new assault on everything and every person who had ever dealt him a slight, real or imagined. Gothard would not give up until they were all destroyed.

With shaking hands, Kerrec pulled on breeches and coat and boots. It was halfway between midnight and dawn. The school was asleep. Even the cooks had not yet awakened to begin the day’s baking.

In the stillness of the deep night, the Call grated on his raw edges. He had enough power, just, to shut it out.

He went to the one place where he could find something resembling peace. The stallions slept in their stable, each of them shining faintly, so that the stone-vaulted hall with its rows of stalls glowed as if with moonlight.

Petra’s stall was midway down the eastern aisle, between the young Great One Sabata and the Master’s gentle, ram-nosed Icarra. Kerrec’s friend and teacher cocked an ear as he slipped into the stall, but did not otherwise interrupt his dream.

Kerrec lay on the straw in the shelter of those heavy-boned white legs. Petra lowered his head. His breath ruffled Kerrec’s hair. He sighed and sank deeper into sleep.

Even here, Kerrec could not sleep, but it did not matter. He was safe. He drew into a knot and closed his eyes, letting pain and self-pity drain away. All that was left behind was quiet, and blessed emptiness.

Valeria knew that she was dreaming. Even so, it was strikingly real.

She was sitting at dinner in her mother’s house. They were all there, all her family, her three sisters and her brothers Niall and Garin, and even Rodry and Lucius who had gone off to join the legions. The younger ones looked exactly as they had the last time she saw them, almost a year ago to the day.

She was wearing rider’s clothes. Her sister Caia curled her lip at the grey wool tunic and close-cut leather breeches. Caia was dressed for a wedding in a dress so stiff with embroidery that it could have stood up on its own. There were flowers in her hair, autumn flowers, purple and gold and white.

She glowered at Valeria. “How could you run away like that? Don’t you realize how it looked? You ruined my wedding!”

“There now,” their mother said in her most quelling tone. “That will be enough of that. You had a perfectly acceptable wedding.”

Caia’s sense of injury was too great even to yield to Morag’s displeasure. “It was a solid month late, and half the cousins couldn’t come because they had to get in the harvest. And all anyone could talk about was her.” Her finger stabbed toward Valeria. “It should have been my day. Why did she have to go and spoil it?”

“I didn’t mean—” Valeria began.

“You never do,” said Caia, “but you always do.”

That made sense in Caia’s view of the world. Valeria found that her eyes were stinging with tears.

Rodry cuffed Valeria lightly, but still hard enough to make her ears ring. “Don’t mind her,” he said. “She’s just jealous because her lover is a live smith instead of a dead imperial heir. That’s how girls are, you know. Princes, even dead, are better than anything else.”

“Kerrec is not dead,” Valeria said.

“Prince Ambrosius lies in his tomb,” said Rodry. “It’s empty, of course. But who notices that?”

“That was his father,” Valeria tried to explain, “being furious that his heir was Called to the Mountain instead of the throne. He declared him dead and stopped acknowledging his existence until there was no other choice. Isn’t that what Mother has done to me? I’ll be amazed if she’s done anything else.”

“Mother knows you’re alive,” Rodry said. “She’s not happy about it, but you can hardly expect her to be. She had a life all planned for you, too.”

“So did the gods,” said Valeria. “Even Mother isn’t strong enough to stand in their way.”

“Don’t tell her that,” her brother said, not quite laughing. He bent toward her and kissed her on the forehead. “I’ll see you soon.”

She frowned. “What—”

The dream was whirling away. The end of it went briefly strange. It was dark, a swirl of nothingness. She dared not look into it. If she did, she would drown—all of her, heart and soul and living consciousness. Every part of her would be Unmade.

The Unmaking blurred into the bell that summoned the riders to their morning duties. Valeria sat up fuzzily. The dream faded into a faint, dull miasma overlaid with her family’s faces.

Kerrec was gone. He had got up before her, as all too usual lately.

She would be late if she dallied much longer. She stumbled out of bed, wincing at the bruises that had set hard in the night, and washed in the basin. The cold water roused her somewhat, though her mind was still full of fog. She pulled on the first clean clothes that came to hand and set off for the stables.

Half a dozen more of the Called came in that morning, and another handful by evening. There had never been that many so soon after the Mountain began its singing. Some of the younger riders had a wager that the candidates’ dormitory would be full by testing day.

That would be over a hundred—twelve eights. One or two wagered that even more would come, as many as sixteen eights, which had not happened in all the years since the school was founded.

“We’ll be hanging hammocks from the rafters,” Iliya said at breakfast after the stallions had been fed and their stalls thoroughly cleaned. The thought made him laugh. Iliya was a singer and teller of tales when he was not studying to be a rider. He found everything delightful, because sooner or later it would go into a song.

Paulus was as sour as Iliya was sweet. He glared down his long aristocratic nose and said, “You are all fools. There has never been a full complement of candidates, not in a thousand years.”

“There was never a woman before last year,” Batu pointed out from across the table. He was the most exotic of the four, big and broad, with skin so black it gleamed blue. He had never even seen a horse before the Call drew him out of his mother’s house, far away in the uttermost south of the empire.

Valeria, most definitely the oddest since she was the first woman ever to be Called to the Mountain, offered a wan reflection of his wide white smile. “Are you wagering that more will come?”

“That’s with the gods,” he said.

“More females.” Paulus shuddered. “Even one is too many.”

“Everything’s changing,” Batu said. “We’ll have to change with it. That’s what we were Called for.”

“We were Called to ride the white gods in the Dance of Time,” Paulus said stiffly. “That is all we are for. Everything leads to that. Nothing else matters.”

“I’m rather partial to wine and song myself,” Iliya said. He drained his cup of hot herb tea and licked his lips, as satisfied with himself as a cat.

Valeria was long accustomed to his face, but once in a great while she happened to notice that in its way it was as unusual as Batu’s. In shape and coloring it was ordinary enough, with olive-brown skin and sharply carved features, but he was a chieftain’s son from the deserts of Gebu. The marks of his rank were tattooed in vivid swirls on his cheekbones and forehead.

The Call had brought them here from all over the empire. They had passed test after test, and were still passing them—as they would do for as long as they served the gods on the Mountain.

She looked from her friends’ faces to others in the hall. Most of the lesser riders were there this morning. The four First Riders dined in their own, much smaller hall, usually with the Master of the school for company. Today Master Nikos was here, sitting at the head table with a handful of Second Riders.

He caught her glance and nodded slightly. Valeria’s existence was an ongoing difficulty, but after she had brought all the stallions together to mend the broken Dance, he had had to concede that she belonged among the riders. To his credit, he had accepted the inevitable with good grace—which was more than could be said for some of the others.

He was probably praying that all of this year’s Called were male. She could hardly blame him. They had troubles enough as it was.

She pushed away her half-full bowl and rose. The others had had the same thought. There was a classroom waiting and a full morning of lessons, then a full afternoon in the saddle.

Iliya danced ahead of her, singing irrepressibly, though Paulus growled at him to stop his bloody caterwauling. Batu strode easily beside Valeria. He was smiling.

It was a good morning, he was thinking, clear for her to read. Most mornings were, these days, though the school had come through a hell or two to get there.

Maybe there were more hells ahead. Maybe some would be worse, but that did not trouble him, either. Batu, better than any of them, had mastered the art of living as the stallions did, in the perpetual present.