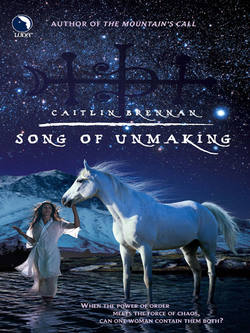

Читать книгу Song Of Unmaking - Caitlin Brennan - Страница 16

Ten

ОглавлениеIliya won his wager—almost. By the first day of the testing, sixteen eights of the Called had come in, less one. They had had to open one of the long-unused dormitories, and all the First and Second Riders were called on to oversee the testing of each eight and the final, anomalous seven.

There had never been anything like it. They were all male—that was a relief to the older riders—but they were not all boys or very young men. Some were older than Kerrec. One was a master of the sea magic. Several were journeymen of various magical orders, and some of those were close to mastery.

“The gods are in an antic humor,” Master Nikos said the night before the testing began.

He had invited the First Riders to dinner in his rooms. That was tradition, but this year the celebration was overlaid with grief. A year ago, three of the four had been Second Riders. Their predecessors had died in the Dance of the emperor’s jubilee.

Tonight they had saluted the dead, then resolutely put the memory aside. This was a time for thinking of the future, not the past.

“It’s good to know we have a future,” Andres said.

He was the oldest of them, and he seemed least comfortable in the uniform of a First Rider. He had been a Second Rider for twenty years and would have been content to stay at that rank for another twenty. His gift was for teaching novice riders and overseeing the Called.

He did not know how valuable he was. That was humility, Kerrec thought. Kerrec was sadly deficient in that virtue. He had not been born to it and he had shown no aptitude for it since.

Tonight Andres was more at ease than he had been since Nikos ordered him—on pain of dismissal—to accept his new rank. The Called were his charges, and he had come to know them all well. “They are remarkable,” he said. “There’s more raw power in them than I’ve ever seen.”

“More trained power, too,” said Gunnar. He had been a Beastmaster when he came, one of the few before this year who had had training in another order. He had just made journeyman when he was Called. “The Masters of the orders may take issue with it, if it seems they’re going to make a yearly habit of losing their best to the Mountain.”

“This may be an anomaly,” Curtius said. Next to Kerrec he was the youngest, but as if to compensate for that, he tended to take the reactionary view in any discussion. “After all we lost in the emperor’s Dance, the gods are giving us this great gift. Next year, maybe, we’ll be back to four or five eights each spring, and the usual range of ages and abilities.”

“Or not,” Gunnar said. “The world is changing. It’s not going back to what it was before, no matter how hard any of us tries.”

“You don’t know that,” said Curtius.

Gunnar glared at him under thick fair brows. He was a huge man from the far north. People there had accepted the empire, but they shared blood with the barbarian tribes. Some said they shared more than that—that they were loyal not only to their wild kin but to the One God who stood against the many gods of Aurelia.

Gunnar was a devoted son of the empire in spite of his broad ruddy face and his mane of yellow hair. “Have you been blind when you ride the Dance? Even in schooling, the patterns are clear. They’re not the same as before.”

“They’ll shift back,” Curtius said stubbornly. “They always do. We’ll make sure of it ourselves, come the Midsummer Dance.”

“Will we want to?” Gunnar demanded. “Think for once, if you can. We were locked into patterns that almost cost us the empire. It took a terrible toll on the school. Maybe we need to change.”

“Change for the sake of change can be worse than no change at all,” Curtius said.

Gunnar rose to pummel sense into him, but Nikos’s voice quelled them both. “Gentlemen! Save your blows for our enemies.”

“Gods know we have plenty of those,” Gunnar said, subsiding slowly. He kept a grim eye on Curtius.

Kerrec sat in silence. He had learned long since that wine did not blunt the edges. It made them worse. It helped somewhat to focus on the others’ voices, even when they bickered.

This would end soon enough. Then there would be the night to endure, and after that the days of testing. He did that now. He counted hours and days, and reckoned how he would survive them.

Master Nikos caught Kerrec as they were all leaving, slanting a glance at him and saying, “Stay a moment.”

Kerrec sighed inwardly. The others went out arm in arm, warm in their companionship. Watching them made Kerrec feel small and cold and painfully alone.

He stiffened his back. That was his choice. He had made it because he must.

Master Nikos had stood to see his guests out of the room. Once they were gone, he sat again and fixed Kerrec with a disconcertingly level stare.

Kerrec stayed where he was, on his feet near the door. He was careful to keep his face expressionless. So far he had evaded discovery, but this was the Master of the school. If anyone could see through him, it would be Nikos.

“You’re looking tired,” the Master said. “Will you be up for this? It’s a lot of candidates to test—and as skilled as the others are, they haven’t been First Riders long. It’s all new to them.”

“Not to Andres,” Kerrec said. “Gunnar is the best trainer of both riders and stallions that we have. They’ll do well enough.”

“And Curtius?”

Kerrec lifted a shoulder in a shrug. “He’ll rise to it. If he doesn’t, we’ll find a Second Rider who can take his place.”

The Master sighed. They both knew that was not nearly as easy as it sounded. But when he spoke, he said nothing of it. “There’s something else.”

Kerrec’s back tightened. Valeria, of course. The rider-candidate who could master all the stallions. The only woman who had been Called to the Mountain in a thousand years.

They had been evading the question of her all winter long. In the meantime she had settled remarkably well among the rest of the candidates of her year. Sometimes the elder riders could almost forget that she was there.

Now spring was past and the Called were ready to be tested. For that and for the Midsummer Dance that would follow, they needed their strongest riders. She was the strongest on the Mountain—not the most skilled by far, but her power outshone the greatest of them.

But Nikos said nothing of that. He said, “One of the guests for the testing has asked to see you.”

Kerrec had not been expecting that at all. Of course he knew that the guesthouses were full. So were all the inns and lodging houses. Half the private houses in the citadel had let out rooms to the friends and families of the Called.

They were all there to witness the final day of the testing. Kerrec could not imagine who would be asking for him by name. There were noblemen among the Called, but none related to him.

Maybe it was someone from his travels for the school, back before the broken Dance, when a First Rider could be spared to ride abroad. “So,” he said, “where can I find this person?”

“In the guesthouse,” Nikos answered. “The porter is expecting you.”

Kerrec bent his head in respect. Nikos smiled, a rare enough occasion that Kerrec stopped to stare.

“Go on,” said the Master. “Then mind you get some sleep tonight. You’ll be needing it.”

Sometimes, Kerrec thought, this man could make him feel as young as Valeria. It was not a bad thing, he supposed. It did not keep him humble, but it did remind him that he was mortal.

Once Kerrec had left the Master’s rooms for the solitude of the passage and the stair, he gave way briefly to exhaustion. Just for a moment, he let the wall hold him up.

He should go to bed. The guest, whoever it was, could wait until he had time to waste. He needed sleep, as the Master had said.

He needed it—but it was the last thing he wanted. In sleep was that hated voice whispering spells that took away yet more of his strength. Every night it was stronger. It seemed to be feeding on the Mountain’s power—but surely that was not possible. Apart from the white gods, only riders could do that.

Kerrec shuddered so hard he almost fell. If an enemy could corrupt the Mountain itself, even the gods might not be able to help the school. They would be hard put to help themselves.

Resolutely he put that horror out of his mind. The riders were weakened—perilously so—but the white gods were still strong. None of them had been corrupted or destroyed.

For now, he had a duty to perform. The Master had made it clear that he was to oblige a guest.

He straightened with care. If he breathed deeply enough, he could stand. After a moment he could walk.

Once he was in motion, he could keep moving. The guesthouse was not far at all, just across the courtyard from the Master’s house. A lamp was lit at its gate, and the porter was waiting as Nikos had said.

The old man smiled at Kerrec and bowed as low as if Kerrec had still been the emperor’s heir. “Sir,” he said. “Upstairs. The tower room.”

It was a nobleman, then. Kerrec wondered if he should be disappointed.

He bowed and thanked the porter, though it flustered the man terribly, and gathered himself to climb the winding stair. It was a long way up, and he refused to present himself as a feeble and winded thing. He took his time and rested when he must.

He was almost cool and somewhat steady when he reached the last door. The doors along the way had had people behind them, some asleep and snoring, others talking or singing or making raucous love. There was silence at the top, but a light shone under the door. He knocked softly.

“Enter,” said a voice he knew all too well.

His sister was sitting in a bright blaze of witchlight, with a book in her lap and a robe wrapped around her. She bore a striking resemblance to Valeria—much more so than he remembered. Valeria had grown and matured over the winter. Briana was some years older, but in that light and in those clothes, she could have been the same age as Valeria.

“What in the world,” Kerrec demanded, “are you doing here?”

“Good evening, brother,” Briana said sweetly. “It’s a pleasure to see you, too. Are you well? You look tired. How is Valeria?”

Kerrec let her words run past him. “You should never have left Aurelia. With our father gone to war on the frontier and the court being by nature fractious, for the princess regent to come so far from the center of empire—”

“Kerrec,” Briana said. She did not raise her voice, but he found that he had nothing more to say.

That was a subtle and rather remarkable feat. Kerrec had to bow to it, even while he wanted to slap his sister silly.

She closed her book and laid it on the table beside her chair, then folded her hands in her lap. “Sit down,” she said. “I suppose you’ve had enough wine. I can send for something else if you’d like.”

“No,” Kerrec said, then belatedly, “thank you. Tell me what you’re doing here.”

“First, sit,” she said.

Kerrec sighed vastly but submitted. Briana had changed after all. She was more imperious—more the emperor’s heir.

Once he was sitting, stiffly upright and openly rebellious, she studied him with a far more penetrating eye than Master Nikos had brought to bear. “You look awful,” she said. “Haven’t you been healing? You should be back to yourself by now. Not—”

Kerrec cut her off. “I’m well enough. I am tired—we all are. We lost a great store of power when our riders died. Now with so many of the Called to test, we’re stretched to our capacity.”

Briana’s eyes narrowed. He held his breath. Then she said, “Don’t push yourself too hard. You’ll make everything worse.”

“I’ll do,” Kerrec said with a snap of temper. “Now tell me. What brings the regent of the empire all the way to the Mountain when she should be safe in Aurelia?”

“I’m safe here,” she said. “I rode in with the Augurs’ caravan. There’s a flock of imperial secretaries camped in a house by the south gate. We’re running relays of messengers. And if that fails, there’s a circle of mages in Aurelia, ready to send me word if there’s even a hint of trouble.”

Kerrec had to admit that she had answered most possible objections—except of course the most important one. “The imperial regent is required to perform her office from the imperial palace.”

“The palace is wherever the emperor or his regent is.” Briana leaned toward him. “Come off your high horse and listen to me. I was summoned here. I had a foreseeing.”

That gave Kerrec pause—briefly. “You are not that kind of mage.”

“I am whatever kind of mage the empire needs,” Briana said. She was running short of patience. “I have to be here for the testing. I don’t know why—I didn’t see that far or that clearly. Only that I should come to the Mountain.”

“What, you were Called?”

“You, of all people, should not make light of that,” she said. “And no, I am most definitely not destined to abandon my office and become a rider. There’s something in the testing that I’m supposed to see. That’s all.”

Kerrec wondered about that, foolishly maybe, but maybe not. His power was broken but not gone. Flashes of understanding still came to him.

He let go his attack of temper. Much of it was fear, he had to admit. He was afraid for her safety and terrified that she would see what had become of him.

She saw no more clearly than anyone else—and as she had said, she was safe on the Mountain. He sighed and spread his hands. “Well then. You’re here. There’s no point in sending you away.”

“Even if you could,” she said.

He was sorely tempted, again, to hit her. He settled for a scowl.

She laughed. “You’re glad to see me. Admit it. You’ve missed me.”

He refused to take the bait. She kept on laughing, reminding him all too vividly of the headstrong child she had been before he was Called from the palace to the Mountain.

When finally she sobered, she said, “You should go to bed. You have three long days ahead of you.”

“I do,” he said. But he did not leave at once. It was harder to go than he would have thought. Even as annoyed as he was with his sister, he felt better than he had since he could remember.

“Listen,” she said. “Why don’t you stay here? It’s ungodly late, and there’s a maid’s room with no one in it. I promise I’ll kick you out of bed before the sun comes up.”

The temptation was overwhelming. He could think of any number of reasons to resist it. Still, in the end, weakness won. “An hour before sunup,” he said as the yawn broke through.

“An hour before sunup,” she agreed with a faint sigh. Maybe she was regretting her impulse.

Or maybe not. He never could tell with any woman, even his sister. Women were mostly out of his reckoning.

He knew already that with her there to watch over him, he was going to sleep well, maybe even without dreams. That alone was worth a night away from his too-familiar bed.