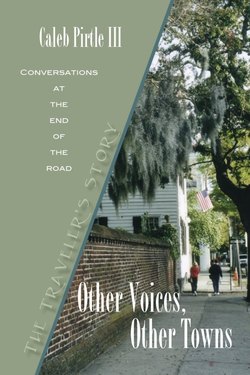

Читать книгу Other Voices, Other Towns: The Traveler's Story - Caleb Pirtle III - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Flat Rock, North Carolina Pop: 2,565

ОглавлениеThe Scene: Carl Sandburg had already become a Pulitzer-Prize winning author, a poet of national acclaim, minstrel, lecturer, and biographer by the time he moved with his family to a mountain farm in the Blue Ridge highlands of North Carolina in 1945. The estate was called “Connemara” and had been built prior to the War Between the States. It served as home for Christopher Memminger, the Secretary of the Confederate Treasury. But since the Confederacy had little money, there was little for him to do. He remained as a gentleman farmer, far removed from the fighting, during the bitter years of conflict.

The Sights: Sandburg’s twenty-two years at Connemara were productive ones. He published poems, children’s literature, fiction, non-fiction, and even earned his second Pulitzer Prize. He never got around to framing either of the awards. He worked most of the night while it was quiet and still, writing wherever his imagination carried him. He dealt with words while his wife raised goats on the farm. The Carl Sandburg Home is a National Historic Site, open every day except Christmas. The rooms are much as the Sandburgs left them, warm and inviting, inspiring and restful. Books and personal items are scattered throughout the house, and it appears as though the family may return at any moment from a morning or afternoon walk. The house, with seventeen thousand volumes of books from Sandburg’s own collection, is filled with the presence of a spirited man whose writing echoed loudly the voice of the American people.

The Story: His was a curious and a simple life. He would have it no other way. He was a common man who found a curious sense of belonging among common men in common places under common circumstances.

Hidden away among them, he discovered the uncommon rhythm of a life that possessed shape and form but little definition and hardly any meaning at all. He heard only the odd cadence of a nation’s voices, often as loud as thunder, sometimes as soft as a whisper, and they spoke to him, and he spoke for them, and very seldom did their diffident collection of words ever rhyme or need to.

His was a crooked road with twists and turns and crossroads, and he seldom knew which road to take, so he tried to take them all. He was a vagabond in the wayward midst of an aimless journey. It could have turned out far different than it did.

Carl Sandburg was a quiet and gentle little man who wandered adrift in a strange world even when he wasn’t lost, and he was never lost. He simply wanted to know what lay beyond the next bend in the road, around the next corner, over the next hill, and who might be waiting for him when the day ended and the bright city lights gave way to the soft glow of moonlight.

The narrow highway stretched out before him, and it was, as it had always been, a dead end. Like a fly in the ragged web of a spider, he seldom knew what to do next.

It was not the easiest of times. He had been born on a corn shuck mattress, the son of a Swedish blacksmith who could not write his name, not in English anyway. The birth certificate referred to the child as Carl August, and his family was determined for the boy to be far removed from the culture of the Old Country. He would speak the language of a bold new land. None would ever speak it with more eloquence.

But mostly, during those early years, Carl just listened, and the soul of those who fought and survived a hard life became his own soul, his own conscience. He wondered what God had chosen him to do with his life, and he found few options.

None of them dealt with a pen and paper.

It could have turned out far different.

The boy, at the mercy of a financial depression that swept the country in the late 1800s, quit school in the eighth grade. He never had a home for very long.

His father was always on the move.

A better job, a better day, a better life always lay somewhere ahead of him. He chased but never caught it.

Carl was abandoned with a scattered assortment of newspapers, magazines, and books to read. He crawled between their covers and closed the pages around him.

He had no other place to go.

Carl Sandburg dressed in old clothes even when he became famous, and fame was one of the few words that escaped his vocabulary. Given his choice, he preferred a simple meal of homemade soups and dark bread.

He had never been a stranger to poverty, and the bad times hardened him just as they had strengthened his father. As a boy, he dug his garden and raised vegetables. He delivered newspapers, scrubbed brick from demolished homes, and cleaned brass cuspidors in a barbershop.

He distributed handbills for twenty-five cents a day and worked as a milk slinger on a milk wagon route for twelve dollars a month and dinner on most nights. Carl washed bottles in a pop bottling plant, worked as a water boy for mules and men as they graded the hills where trolley cars would run, rented rowboats, stacked heavy blocks of ice in an ice house, and sponged down sweating horses at the gamblers racetrack.

Carl could have been discouraged. He wasn’t

Young, disconnected, and growing older, he was trapped in the midst of a great struggle. It was pulling him somewhere. He had no idea where the struggle would take him.

Carl asked for little. He expected little. He found much on a road that allowed him to watch the “fog come in on little cat feet,” witness “a sunset sea-flung, bannered with fire and gold,” and stumble across “a pier running into a lake straight as a rifle barrel.” He could not escape the scenes forged in the back reaches of his mind, and they would not leave him alone. He had no idea what to do with them.

It could have turned out far different.

Carl would always know “hours as empty as a beggar’s tin cup on a rainy day, empty as a soldier’s sleeve with an arm lost,” and he had seen “where the music goes when the fiddle is in the box.”

These became the sights he could not forget, the subtle sounds he heard, the pain he felt, the loneliness that gripped him on a road with no end. He was haunted by the memories of a face, a love, a thought he had somehow left behind. None of them, at the moment, were lines of poetry.

He scribbled a little now and then but generally had no use for writing pads. The unforgiving battle for survival was much more important to him. Maybe somewhere along the way from one small, out-of-the-way town to another, he would find a job, a trade, a livelihood that could put a dollar or two in a pocket that was mostly as empty as the streets he walked. A young man’s ambition never stretched farther than his next meal, which often seemed thousands of miles away.

Carl traveled with panhandlers, tramps, thieves, and hoboes that took one road, then another, found one day and lost another, worked for a dime, worked for a meal, and possessed a proud dignity because they endured when the odds had given them up for dead.

Carl said he left home with his hands free, “no bag or bundle, wearing a black sateen shirt, coat, vest, and pants, a slouch hat, good shoes and socks, no underwear, in my pockets a small bar of soap, a razor, a comb, a pocket mirror, two handkerchiefs, a piece of string, needles and thread, a Waterbury watch, a knife, a pipe and a sack of tobacco, three dollars and twenty-five cents in cash.” He considered himself a well-dressed hobo until the rains, dust storms, and railroad yards left his clothes as wrinkled and forlorn as his life.

His father scowled as he watched the boy walk away. His mother cried.

The road traveled in only one direction. It never brought anyone back. It would go forever or end at the edge of the earth. As he wrote: “I don’t know where I’m going, but I’m on my way.”

The education of Carl August Sandburg had begun. His teachers would become the great unwashed, the common man in common places, mostly with uncommon ideas.

He rode the rails, slept in train yards or fifteen-cent flophouses, watched the cities come and go, saw the countryside change from mountains to wheat fields, then fall away in the long shadows of thick forests.

The rails and the rivers led him on, always on, and he did not know where they would take him, or if they would take him anywhere at all. Carl chopped wood, picked pears and apples, had a fight or two, was thrown off a few trains, saw the inside of a jail cell from time to time, and shared coffee, stale bread, and burnt frankfurters with those huddled masses who warmed the campfires of a hobo jungle. They came from all parts of a struggling country, asking for little, expecting even less.

He listened to their voices, their stories, their hopes, their anger, and the hurt that dwelled deep inside their souls. Long before he realized it, their trials and their tribulations had become part of his own.

Twice he fell asleep while riding the bumpers of a train.

Twice he almost died. Many lay in unmarked graves along the side of the road, their names lost, their faces forgotten, their ambitions turning to ashes and dust. It was as though they had not traveled the road all.

Gone like the winds or the tides without anyone to mourn them.

Carl could have been one of them.

It could have turned out far different.

He wrote: “I was meeting fellow travelers and fellow Americans. What they were doing to my heart and mind, my personality, I couldn’t say then nor later and be certain. I was getting a deeper self-respect than I had had back home in Galesburg (Illinois) . . .

“What had the trip done to me, I couldn’t say. It had changed me … Away deep in my heart now I had hope as never before. Struggles lay ahead, I was sure, but whatever they were I would not be afraid of them.”

Carl still had no idea what to do with himself. Words and lines of free verse were forming in his brain. He had no idea what to do with those either. Why write them down? Who would ever read them?

He tried one trade, then another, and none really appealed to him. Carl drove a milk truck, sandpapered houses for a painter, and borrowed every book he could find to read.

While the burning, splintered remnants of the battleship Maine lay scattered upon the ocean, he enlisted in the army simply because President McKinley had declared war.

Carl wound up in Cuba by the time the fighting had ended. His was not a bloody tour, he said, but a dirty, lousy affair all the same. Long marches. Hard roads. Fifty-pound backpacks. Never-ending rains. Mosquitoes with blood on their faces, his blood. And graybacks in his uniform.

Carl stood tall during the most miserable and demanding of times and impressed his commanding officer so greatly that, with only an eighth grade education, he was nominated as a candidate for West Point.

That’s where his life changed for good.

Carl was still smitten with his “endless unrest.” He had spent years looking for a trade, a vocation, even a profession, and he remained on a hard, shadowed road that was leading him from one dead end to another.

Somewhere in the back of his mind, he began to concoct the idea that maybe he had the ability to put a pen and ink to paper and write. His free verse read like prose, his prose like poetry, full of strength and emotion.

The common man did not read poetry.

The common man would read Carl Sandburg.

It was as though he looked at the world through their eyes.

As his granddaughter said, “In his work, he turned often to the jargon of the people about which he wrote. His most poetic images and phrasing would not seem alien to a store clerk or a steelworker.”

But he wrote alone, preferred the quiet of the night, and remained a vagabond in search of himself. Carl bought bananas for a dime a dozen and a loaf of stale bread for a nickel.

He lived and ate simply. He traveled the back roads on a rented bicycle, pedaling from farm to farm and peddling stereoscopes throughout Wisconsin. Winding roads. Never ending.

As restless as always.

But the job did give him the freedom to wander alone and think, to sit beneath the trees in the shank of the day and read, to linger at roadsides and write all kinds of formal verse. The poems were not so good he always said, “but I had the lingering, and that was good.”

The lingering would never leave him. His curious journeys had shaped him. The common man molded him. He read so many words along the way, and finally he began to put his own words on paper. He wrote them his way, free and unstructured, powerful and filled with imagery that came from the mind and emotion of a man who saw America at its best, at its worst, and forgot nothing. It was his own style. He fit no other.

It could have turned out far different.

At the end of that unpredictable and circuitous road, Carl Sandburg found pen and paper and finally an old typewriter. He worked on newspapers and magazines, sat down and wrote the Rutabaga Stories for children, and, during the quiet solitude of a long night, began writing the free verse of his poetry.

He had possessed the soul of a poet all along.

Although a few holier than thou historians said that a poet’s pen should never meddle with history, Carl wrote the six-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln, which may well be the finest biography of them all.

His were the stories of a man, a President, and an age. He told his publisher that he thought the Lincoln book might be “a sort of history and Old Testament of the United States, a joke almanac, prayer collection, and compendium of essential facts.”

The final four volumes, The War Years, contained more than 1.75 million words, more than the Bible or the complete works of William Shakespeare.

His Lincoln biography, which took almost two decades to research and write, earned Carl Sandburg his first of two Pulitzer Prizes.

Carl Sandburg wrote with his old typewriter mounted atop an orange crate.

“Why not a desk?” he was asked.

Carl shrugged.

“Surely you can afford a desk.”

Carl Sandburg smiled. “If General Grant could command his troops from an old crate,” he said, “I can certainly write about it from one.”

So he did. Carl Sandburg championed the lost cause of “the Poor, millions of the Poor, patient and toiling; more patient than crags, tides, and stars; innumerable, patient in the darkness of the night.”

He celebrated the universal toil, blood, and dreams among lovers, workers, loafers, fighters, players, cowboys, factory workers, and gamblers. As he said at the end of his days, “If God had let me live five years longer, I should have been a writer.”

It could have turned out far different.

If, after his sojourn in the Spanish American War, Carl Sandburg’s nomination to West Point had been accepted, he might well have settled down to a military career as an officer and a gentleman.

His landscape would have been fogged by the gunpowder of two World War battlefields instead of defined by his poems.

Instead, Carl Sandburg became a poet. He had no other choice. West Point glanced over his application and rejected him.

On his entrance exam, Carl Sandburg failed grammar.

In Connemara, his Flat Rock, North Carolina Home, Carl Sandburg wrote his poetry in the late hours of the night with his typewriter perched on an orange crate.