Читать книгу Other Voices, Other Towns: The Traveler's Story - Caleb Pirtle III - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Elkmont, Tennessee. Pop: 0

ОглавлениеThe Scene: The Great Smoky Mountains National Park reaches out and touches the sky for eight hundred square miles. It’s big. It is overwhelming. There are both high roads and low roads into areas of virtual isolation, including seven hundred miles of hiking and horseback paths.

One of them is a rugged sixty-eight-mile section of the Appalachian Trail that stretches from Maine through Georgia. Many, however, prefer to stick with the paved roads. One winds thirty-five miles from the resort city of Gatlinburg, Tennessee, to Cherokee, North Carolina, and another twists its way through the high timbered ridges from Gatlinburg into the living history farmstead of Cades Cove.

The Setting: Elkmont is more or less a ghost town with a campground and historic district that showcases pioneer cabins dating back to the 1830s and ‘40s. The town was established by the Little River Lumber Company in 1908 as a base for its logging operations.

Four years later, the famed and notorious Wonderland Park Hotel was built on the crest of a hill overlooking Elkmont, and the resort became the favorite hideaway for Tennessee’s wealthy and socially elite. The town itself was located in a narrow valley that lay at the junction of Little River and Jake’s Creek. Many came; all left but one. He stayed on for a long time.

The Story: No one ever dropped by Lem Ownby’s place on their way to anywhere else. Lem Ownby did not live on the way to anywhere else. His gray, weathered cabin hunkered down in a little grassy hollow at the far end of a paved road that became a dirt road that became a pair of wagon ruts, then beyond the brush and over a ridge stopped for good.

Stooped and wearing faded blue overalls, Lem Ownby shuffled his way along the neat row of rain-stained beehives that stood like aging tombstones in a world he hadn’t seen for almost twenty years. The mountains, strong and forgiving, kept their burly arms around him. The creek out back soaked up his thirst. The bees gave him their sourwood honey in case anyone with a few extra dollars came down that paved road that became a dirt road, then stopped for good when the wagon ruts ran out.

The last time I saw him, Lem Ownby was ninety-two and alone. His shoulders were stooped, his voice gentle. He was wearing a broad-brimmed straw hat that had probably been new before the war, World War II. He kept the hat clamped down on his head to keep the rain off his face. He no longer needed it to keep the sun out of his eyes. The sun had not bothered his eyes for a long time. Lem Ownby was the old man of the mountains. He told me, “I sometimes take spells of being lonesome, but like a bellyache, it always passes.”

Behind him, the Great Smoky Mountains muscled across the timbered backbone of Tennessee, rising up into a blue mist that touched their wounded gorges like swabs of cotton and gauze. Until 1940, bib-overalled settlers, on farms beside country roads where no one hardly ever traveled, scratched out meager livings on scattered patches of soil mortised between stump and rock. “The land was so steep,” Lem told me, “you had to plow with one hand and hold on with the other.”

The sun rose above the mountains far too late in the day. It set beyond the mountains far too early. The tall country was creased with ravines and creeks, the slopes quilted with wildflowers. The earth was old. Pine, oak, hemlock, and yellow poplar all shadowed the wrinkled land that long kept mankind out of its hollows, then protected the few who dared battle their way in and stake claim to soil where only the courageous dared walk. In places, the mountains shut out the sky, and the pathways leading into the dark woodlands seldom found their way back out.

“Have you ever been lost back in this country?” I asked.

Lem Ownby glanced out across a fine purple mist that rolled atop the highlands. I knew it was purple. Lem had no idea. Lem had been blind for decades. He grinned, and said, “No, I don’t guess I’ve ever been lost. But I have been powerfully misplaced from time to time.”

The mountains themselves are ancient, the oldest landmarks on the face of the earth, having watched over Appalachia for two hundred million years, give or take a millennium or two. In 1940 the Great Smokies became a national park, and most families had to give up their raw acreage and move out. A few were allowed to stay. No others would ever homestead those mountains again. All of the original setters were gone.

Save one.

Lem Ownby was the last man on the mountain.

His grandfather had defied the mountains in search of gold, and his parents fought their way into the solemn refuge of the Smokies during the War Between the States.

They brought with them all they needed: a gun for hunting, a broad axe to cut the logs for a home, and a froe to slice the shingles that became a roof. Their philosophy had been a simple one: “If you can’t buy it, make it. And if you can’t make it, just do without it.”

In 1902, at the age of thirteen, Lem Ownby, swinging an axe as tall as he was, worked with his father to build the cabin that now sheltered him.

“It’s just back of beyond,” said the old man. He grinned a tired grin. “It was so far back in the woods, we had to go toward town to hunt.”

The Ownby family had neighbors up on Meigs Mountain and over on Blanket Mountain, where a bright red blanket had been hung atop a rusty wire to designate the official county line. It was seldom seen by anyone who didn’t belong in the high country.

“We did have an educated man come in here one time,” Lem remembered, “but he almost starved to death. He wouldn’t have made it if we hadn’t felt sorry for him and fed him. He was a college man.”

Lem Ownby rubbed his chin and leaned back on the old rocking chair beneath the picture on the wall, the faded photograph with images of a smiling mother and bearded father.

Maybe she was smiling because, in those days, old women knew how to get rid of worrisome warts without going to the doctor, which was good since there were a lot more warts than doctors back in those hard-rock Smoky Mountains.

“Just steal a dishrag,” she had told Lem, “then rub it over the warts. Hide it under a rock and never go back. When the dishrag rots, the warts will go away.”

The warts left. And, after a while, so did all traces of humanity. Only the chimney above Lem Ownby’s cabin mixed its ashen smoke with the blue mist of the mountains.

When the mountain farm boys stumbled awkwardly across the threshold of puberty, they diligently searched the corncribs from barn to barn. When someone found a red ear in the pile, he would have the pleasure and sinful distinction of being able to kiss the girl of his choice, provided he could talk her into such a provocative deed.

“We couldn’t be choosey about the girls,” Lem said.

“Why not?”

“There weren’t many of them.”

“How did you find a wife?” I asked.

“We took whatever was available.”

“And what if you married the wrong girl?”

“My daddy always said, ‘You’ve burnt a blister, now sit on it.’”

The mountains bred strong, self-reliant individuals. Lem Ownby called them stubborn. They were his neighbors, and they had been gone so long he sometimes wondered if he had ever really known them at all.

He remembered the day Ephraim Ogle and John Hampton went up the mountain together to bring down an old mule for plowing. “He’s stubborn and wild,” Ephraim said. “There can’t nobody ride him.”

`John Hampton snorted. He gritted his teeth and rubbed his hands on the back of his overalls. He spit once, then twice. “There ain’t never been a mule I can’t ride,” he said.

John Hampton mounted. The mule ambled slowly, even leisurely, on down the dirt road. John smiled. Nothing to it. He could ride anything. At the mud hole, the mule balked.

He laid his ears back, peeled his eyes, stopped, dug in his heels, and would not take another step. John Hampton yelled. Then he pleaded. Finally he kicked the mule in the ribs. A moment later, he was pulling himself, head first, out of the mud hole.

Ephraim ambled over and said loudly, “He threw you, didn’t he?”

John Hampton shrugged and wiped the mud from his eyes. “Well, he sorta did, and he sorta didn’t,” John replied. “I was aiming on getting off anyway.”

Down in the valley was the dastardly Ephraim Bales. He could hoe corn all day long, some said, without ever standing on Tennessee soil. Ephraim Bales would simply walk across the rocks, find a pile of loose dirt, press a corn kernel into the earth, then step on to the next stone. His was a hard life. But then, it was never easy living in a two-room cabin with a wife, nine children, and a mother-in-law. Ephraim Bales was known as the meanest man in the valley. He had his reasons. He was feared. He was cursed. Men rode miles out of their way to keep from passing his cabin.

No one mourned him when he died. Ephraim Bales was buried in the rich sod of his own backyard, and no one came to the funeral. The pews were as empty as his life had been. On Monday, Bales had stalked off into the woods and cut down a chestnut tree, then hauled it by mule to a sawmill. “Cut it up in planks,” he ordered.

He stacked the planks, threw them in the back of his wagon, and brought them home. “When I die,” he told his wife, “make my casket out of them chestnut planks.”

“Why?”

“So when I go through hell,” he said, “I can go through hell a-cracking.”

“God always did say he was gonna make the devil suffer,” Lem Ownby said as he rocked beside the potbellied stove, beneath a clock that no longer ticked. “He did. He sent Ephraim Bales to old Lucifer.”

As a boy, Lem Ownby made a stab at attending the one-room schoolhouse up on Meigs Mountain. “Mostly it was walking in the front door and out the back one,” he recalled. Crops stood in his way. So did the family chores. “It was hard to read books when you’re going hungry,” Lem said. “What I tried to do was keep from going hungry.”

He headed out into the Smokies and gathered a mess of greens: lamb’s tongue, old field mustard, field cress, crow’s foot plant, and poke shoots. He shrugged, “Daddy always said that if it don’t kill a cow, then it won’t kill us.” The garden was a struggle, and Lem Ownby could not recall any day he had been without a mule and a hoe. “Mostly we raised rocks,” he said. The Ownby family dug up potatoes in the spring and managed to shuck a patch of corn, provided, of course, the ground squirrels didn’t come out, either day or night, and steal a winter’s worth of cobs and kernels. The Ownbys always farmed the steep side of the Smokies, which was the only side they had.

Lem Ownby found that sometimes he could depend on the mule, and sometimes he couldn’t, and sometimes it wasn’t even worth the effort. “Mules have a bad habit of sitting down when they want to and taking themselves a rest,” Lem said, “and you wind up grabbing the blister end of an old hoe and working for yourself.”

The mountains gave him little mercy, when they offered him mercy at all, but they gave him a chance to survive. So Lem Ownby took his broad axe and with a pair of callused hands he almost scalped them bald. The loggers saw dollar signs growing tall and thick on the slopes of the Smokies. They hired men like Lem Ownby, tossed them an axe and crosscut saw, kept them in the timber and working for eleven hours a day, and paid them a dollar fifty every time the sun went down.

“How many trees did you cut?” I asked Lem.

“About a hundred and seventy-five a day,” he said in a quiet voice. “A good timber cutter could do a little better.”

“How selective were you about the trees you cut?”

“If they were on the mountain, we took them down.”

“Were they hardwoods?

“Durn right they was hard.”

So down came the maple, red cherry, buckeye, yellow poplar, and hemlock. “We cut one poplar that was nine feet in diameter,” Lem said proudly. “It was so durn big the flatcar couldn’t hold but one log.”

At first, a team of horses hauled out the timber along an old, dirt skid road. Then came the railroad, and it pushed the loggers higher and into rugged, treacherous terrain where even angels, provided they had good sense, feared to tread. The track finally ended within half a mile from the crest of Clingman’s Dome, playing out at 6,606 feet. The axe and crosscut saw, lethal weapons in lethal hands, left stumps and splintered scars across three hundred and thirty-nine thousand acres.

The Tennessee highlands were almost naked before anyone cried out in 1923 to save them. The government sought to buy the land, but lumber and paper companies did not want to lose their holdings. Those who lived within the hollows did not want to walk away from their homes, such as they were.

The Great Depression changed their minds. They saw the opportunity to pocket quick cash for their farms, and most had never even gotten a glimpse of opportunity before. Didn’t know what it looked like. Only knew it was there staring them in the face.

Some sold. Some went to court, lost, and had to take their money anyway. And a few – because of hardships and old age – were granted a reprieve and given lifetime leases on their homesteads even though the acreage lay deep within a new national park.

One was Lem Ownby.

The old-timers were handed a strict set of regulations. You can’t hunt, they were told. You can’t cut any green trees. And the law says you have to pay a dollar per acre per year. Violate the contract, and you forfeit your land.

A bear raided Uncle Jim Carr’s springhouse. Uncle Jim Carr shot the bear. Uncle Jim Carr was kicked out of the Smokies. Another old-timer cut down a tree in his yard. It had two forks, one dead and one green. He, too, was ushered out of the mountains like a common criminal. Age crept up on the rest.

Lem Ownby lost his neighbors.

He lost most of his land.

Finally he lost his sight. He missed most the voice of man.

Lem Ownby, leaning heavily on his cane, stepped off the front porch and shuffled back toward his fifty beehives. They swarmed his face and covered his hands. It was as though they did not exist at all. Lem Ownby did not rob the hives of their honey. The bees merely left it behind for him to find. He had taken care of them for years, and now they took care of him.

His was a tranquil place, at peace with itself, with the calm wind swinging through the trees and the white water creek singing to the rocks as it rushed out of the mountains.

“Have you ever thought about leaving this valley?” I asked.

“Sometimes.”

Lem Ownby stopped for a moment and leaned against a hive. He shrugged and grinned. “One of these days,” the old man said softly, “I’m gonna go up to where the mountains are higher and prettier, and you don’t get bee stung.”

For him it would be a long wait, a lonesome wait.

Five years later, he lay down one night, closed his eyes, and by morning, the mountains had changed their shape. Higher, perhaps. Maybe even prettier. The constant hum of the bees faded into silence.

Lem Ownby had left home and gone home.

Forever and ever.

Amen.

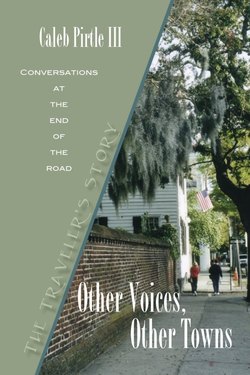

Lem Ownby, blind and alone, sits beside his mountain cabin in the Great Smoky Mountains.

(Photo: J Gerald Crawford)