Читать книгу Trail of Broken Promises - Caleb Pirtle III - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1: The Homes of Their Fathers

ОглавлениеTHE CHEROKEES LOOKED toward the west with diffident, somber eyes, darkened by the shadows of a sunset that had fallen beyond the edge of the earth. It was the land of lost souls, beckoning for the dead to journey back to the stars and fade forever into the night from whence they had come.

To the Cherokees, the east was the refuse of light and sun. They stared with doubt and dismay toward the land where the sun and the light disappeared. It was a fearful place, and they turned their backs to it.

The Cherokees had found peace in the fertile valleys where the earth was old, beneath the solemn, rugged face of Great Smoky Mountains forever veiled by a thin will-o-the-wisp haze that rose up from its hollows and touched the sky. And the Cherokees knew why: their Adawehis, their story tellers, had told them.

Selfishness had crept into the world, causing men to quarrel and fight. The Chiefs of two tribes counseled together, even smoked the pipe, then grew angry and battled for seven days and nights. The Great Spirit frowned, for men were forbidden to smoke the pipe until they had made peace. Men needed to be reminded of their obligations.

So, the Great Spirit reached down and turned the belligerent old men into gray-colored flowers, causing them to grow wherever friends and relatives had quarreled. He hung the smoke of the pipe across the mountains until all peopled learned to live together in peace.

The Cherokees prospered in the umbrage of their legacy, settled in the highlands of northern Georgia, central Tennessee, and among the misty peaks of the Carolinas. Buffalo, deer, and wild turkey ran within the thickets. And the countryside became a quilt-work of color, woven by the azaleas, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and magnolia.

The Cherokees had found peace in the land they called home. But they would fight to hold it, even if the smoke clung to the mountains forever.

Women spent their hours in the garden, slopping hogs, caring for the poultry, smoking venison, and tanning hides. The men prepared themselves for war. It was always near, as close as the thunder, and as deadly as the lightning that danced among the pines and hemlock.

As William Fyffe, a South Carolina plantation owner, wrote in 1761, “their greatest ambition is to distinguish themselves by military actions … Their young men are not regarded till they kill an enemy or take a prisoner. Those houses in which there’s the greatest number of scalps are most honoured. A scalp is as great a Trophy among them as a pair of colours among us.”

During the calm days, the Cherokee men fashioned bows, tomahawks, war clubs, and canoes. But when war stalked them, they painted their faces black, streaked with vermillion, and they adorned their hair with feathers.

It was a time, Fyffe recalled, when “there’s nothing heard but war songs and howlings.”

William Bartram, the American botanist who wandered at will through the Indian nations, wrote, “The Cherokees in their disposition and manner are grave and steady; dignified and circumspect in their deportment; rather slow and reserved in conversation; yet frank, cheerful and humane; tenacious of their liberties and natural rights of men; secret, deliberate and determined in their councils; honest, just and liberal, and are ready always to sacrifice every pleasure and gratification, even their blood, and life itself, to defend their territory and maintain their rights.”

Bartram also recognized that some of the younger women happened to be as fair and blooming as the ladies of Europe. He stumbled across a group of maidens who were wearing little or nothing at all as they picked strawberries.

Bartram always remembered them “disclosing their beauties to the fluttering breeze, and bathing their limbs in the cool, flitting streams.” Otherwise, he found them dressed in skirts and short jackets, sometimes wearing moccasins.

The Cherokees built their homes with logs, stripping away the bark and plastering them with a mixture of clay and dried grass. Inside were cane seats, baskets, and buffalo hide chests, all placed upon rugs woven from hemp and designed with the images of birds, animals, and flowers.

To such dwellings the Cherokee men brought their wives after a simple marriage ceremony. The husband would give the bride a ham of venison, his pledge to keep the home filled with game from the hunt. And the bride would hand him an ear of corn, her assurance that she was ready to become a good housewife.

The vows were short; the dancing would go on for hours.

The Cherokees were proud and independent. As Fyffe wrote: “Every warrior is an orator.” And they called themselves “Ani-Yun-Wiya,” the real people, the principal people. But none could read and none could write.

So, the white man called them savage.

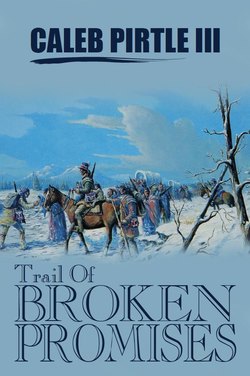

The sensitive wood sculpture of mother and child reflect the

peace and serenity of the Indians before white men came

to take away their cherished lands.

Five Civilized Tribes Museum

Muskogee, Oklahoma

Willard Stone, artist