Читать книгу Trail of Broken Promises - Caleb Pirtle III - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3: Keepers of the Swamplands

ОглавлениеTO THE SOUTH, down toward the great waters, down amidst the saw grass swamps and mangrove thickets, there roamed a scattered band of isolated Indians that the Creeks called Seminole, meaning “wild” or “people who camp at a distance.”

Theirs was a foreboding world that few dared to enter, and even fewer ever found their way back out again. The Seminoles had no identity. They merely misplaced themselves in a river of grass where the land was mostly sea.

They had their war villages and their villages of peace, but mostly they were exiles, fighting to hold on to their last outpost east of the big water that was known as the Mississippi. For a time, the Seminoles united themselves with the Lower Towns of the Creeks, even partaking of the glorious Green Corn Dance as though it were a communion of the soul.

Upon the sacred square they spread soil from the earth where no one had ever walked before. And every fire in town was doused, every floor swept and scrubbed, a way to rid the tribes of the old year and make ready for the new one.

For amongst the Creeks and Seminoles, the new year’s came down in the steaming heat of summer. The religious white drink – the liquid of purification – was brewed black in the kettles. Each family walked forward to secure fresh fire from the sacred flames in the square, and for eight days, the people danced and fasted and drank medicine and played ball as they gave thanks to the gods for the gift of corn, the gift of life in bad times, as well as in good ones.

Everyone was expected to attend the celebration. Those who could not reach the sacred square in time gathered a bundle of green corn, slashed it, then rubbed the juice over their faces and hands. If an escaped or wanted criminal could make it to the festival, he was immediately forgiven for his sins and his crime overlooked, if not forgotten.

War and a treacherous land had taken their toll on the Seminoles. The Spanish came, then the British, and finally the Spanish returned. Once the tribe had numbered 25,000. But by 1763, when they again heard the guns of Spain, only 83 fled from St. Augustine, 80 escaped from Southern Florida, and 108 slipped out of the port at Pensacola.

There were no more. They buried themselves deep in an untrammeled forest, sheltered, but not safe from the rattlesnakes and cottonmouths and malaria and dengue fever that lurked behind the cypress and tangled vines. In Congress, Virginia’s John Randolph turned to a colleague and remarked, “If I were given the choice of emigrating to Florida or to hell, sir, why then, sir, I should choose hell.”

William DuVal, an agent for the tribe, would even journey into the strange river of grass, then write: “I suffered much from drinking water alive with insects, from mosquitoes, intolerable hot weather . . . I have never seen a more wretched tract . . . No settlement can ever be made in this region, and there is no land in it worth cultivation . . . the most miserable and gloomy prospect I ever beheld.”

But it was home and it was good enough for the Seminoles. They only hungered for a place to rest, a chance for survival.

But the white men sought them out. And the white men called them savage.

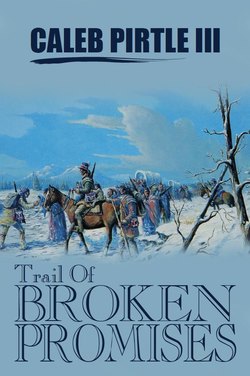

“Uprooted,” carved from a red cedar stump, symbolizes the Five Civilized Tribes that were torn away from their homes and transplanted in Eastern Oklahoma. Willard Stone, the artist, fashioned the carving from a stump, he said, because the tribes had been pulled away from the ground of their birth.

Five Civilized Tribes Museum

Muskogee, Oklahoma

Willard Stone, Artist