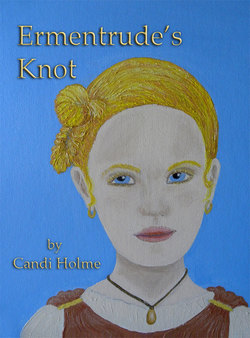

Читать книгу Ermentrude's Knot - Candi J.D. Holme - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter I Return to the Summer Festival 175 CE (Gothiscanza near the Wisla [Vistula] River in current Poland, home of the Gutthiuda tribe)

ОглавлениеI felt pain. It was in my heart. I stood at the fence waiting for him—my father, whom I called Att-a. It had been too long. I only remember snow falling—covering his horse’s tracks when he left with my brother. They had gone off to battle without us. I stayed with Mama. She was ill and needed me, as did my little sister.

Every morning, I stood by the fence, waiting for my father, hoping he’d return. It had been a long winter. Now, the first signs of green appeared on the branches. Tufts of green grass pushed through the snow mounds. Trickles of melting snow dripped from our home’s rooftop. I breathed heavily in the cold of the foggy morning. My breath puffed out of my mouth as I sighed—he’s not coming, I thought.

Hearing shouts, I craned my neck to see past the trees that stood near the river’s edge. Father usually followed the river home. I knew to look there. I was sure I heard shouts. Were they shouts of an enemy approaching? I ran inside to get my weapons. I stood guard. I listened again. I heard horses—more than two. I readied my spear and sword. I waited, tense, but hopeful that it was my father’s horse among others.

“Att-a!” I yelled excitedly, when I saw my father returning on horseback, with my older brother, Adalwulf. Two young men, whom I did not recognize, rode with them.

“You were gone so long! I was afraid you would not return to us. I thought you both were killed, or captured by skōh-sl (ghosts) in the forest.” I said.

I ran to them, as they rode up to our house, almost colliding with my father’s horse. Father looked at me, not having seen me for many months. He lifted me up, and put me on his horse, sitting before him. His arms felt strong as he hugged me.

“Ermentrude, you are prettier than ever,” he said.

I thought my father, Ansgar, was the bravest man in the village. My parents had lived in our village for many years. Father, was a handsome warrior with many scars, from battles in the past. I knew how much my mother missed riding off into battle with him. In the past, my mother, Ermien, always followed Father, to tend the wounded and rally the warriors in battle. She had witnessed the bloodshed that resulted from raids on other tribes.

Our fearless warriors would advance toward our enemy’s army and cavalry, holding their round, wooden shields and spears, or their short swords and their axes. Some of our warriors rode horses into the hoard of enemy soldiers; our artillery hurled heavy rocks onto the enemy’s advancing ranks. I imagined Father in battle when I was young, but shuddered at the thought of him wounded, or worse.

Our warriors fought to defend our land, or to retaliate for cruel deeds against us. We raided enemy villages, took their land, goods, and livestock for our own. Often, our warriors would capture the enemy, returning home with slaves.

We needed many slaves to help with chores around the farm, for there were many hardships. There was little time for pleasure, since clothes needed washing, sewing, and mending. Children needed to be educated in the use of weaponry. Livestock had to be fed, bred, and butchered to be eaten or sold.

There were meals to prepare. My Aunt Gunda, Mama, and I had roasted meat and cooked vegetables for the summer festival over a fire pit in the house, when Father and Adalwulf returned. When Mama saw Father dismounting his horse she let out a cry. Mama ran outside brushing the hair off her face.

“Oh, Ansgar! I missed you over the long winter months! Adalwulf . . . you look so handsome with your beard! You are older now. Soon you will take a wife and not be so eager for my kisses.” Mama embraced each of them.

My little sister, Ava, patiently waited, eager to be lifted high in the air and swung around onto Father’s shoulders. Adalwulf tousled Ava’s blond hair. She squinted up at him and the two young men beside him. She smiled at Father.

“Att-a! We thought you would miss the festival of the gods, and the summer solstice!” I’m glad you are here to share the roast pig and the festivities,” Ava said.

Ava reached up to Father’s chest, as he hugged her. He swung her up, on his shoulders as though she were a woolen cloak.

“Would you cry if we didn’t come?” Father asked. He lowered his gangly daughter of seven years to the ground.

“No, Att-a . . . never! I would only be sad. May I ride your horse, the way Ermentrude does, Att-a?”

“Of course you may! Up you go, but do not wander away. We have a feast to enjoy, and I intend to nibble on your toes, after the roast pig is eaten.” He enjoyed teasing her.

“You wouldn’t, Att-a!” Ava giggled.

Ava and I sat upon Father’s horse, staring at our brother and the two men talking to him. Our parents hugged and kissed, walking toward our home with us still riding Father’s horse. Adalwulf and his two companions dismounted their horses.

“How are my two pretty sisters? Surely you want to meet my two companions,” Adalwulf said.

“Oh, ja, Adalwulf, please tell us who you have brought home with you.” We giggled together, smitten with the two handsome faces gazing at us.

“This is Arnold, my friend,” hugging the taller reddish-blond haired man, “and here is Bertram, my other honorable friend,” slapping him on his shoulder, which awakened dust that had settled there during the six day ride home. “Arnold and Bertram are my closest friends. We have ridden far to arrive here for the festival, so hurry inside and ready our drink and victuals, lovely sisters. We are so hungry, we might bite your tender shoulder, Ermentrude, or your delicious toes, little Ava!” Ava pulled her foot away and screamed; I brazenly stuck out my tongue at him. Ava and I dismounted and headed toward the large wooden home, built by our father and uncles long ago, when I was a child. We entered the doorway to see my uncle and aunt sitting at the table in the kitchen. I moved toward the fire for warmth.

My loving aunt, Gunda, my mother’s sister, and my jovial Uncle Vaclav, with their five children, often sat inside our house around the table, sharing food and stories together. We were a close knit family, sharing chores and bread every day. Our midday meal, consisted of roasted meat, wild birds, and bread, with wild carrots or turnips. We drank fresh milk from our cows; the adults savored mead drawn from my uncle’s barrel.

Soon, my other uncles and aunts would join us, bringing other delightful treats for the meal. They had families, too—at least eight children of their own. So many mouths to feed—thirteen cousins and a couple on the way.

“Aah! There they are!” my uncle Vaclav shouted, as Att-a and Adalwulf appeared with their two guests inside the doorway. “We are so happy to see you at last! I almost cried last night, as a little girl would cry, when you did not arrive home.”

Ava frowned at her uncle. She did not want to be treated as a little girl who weeps for her absent father. Her small female cousins mimicked frowns, as well.

“Hmmm, who are these fine brave warriors you have brought home, Adalwulf?” Uncle Vaclav asked.

“Uncle, they are my most honorable friends . . . Arnold, with a keen eye for the enemy, and Bertram, with a raven’s wisdom for planning attacks,” Adalwulf said, “and this is my amusing Uncle Vaclav, who will try to trick you when you least expect it, so beware of him.

Everyone laughed at Uncle Vaclav, even his wife, Gunda. She had more precautionary advice, such as, what to do when using the latrine in the darkness of the morning. I knew she was trying to scare Arnold and Bertram just a little. They merely chuckled, with amused glances at Adalwulf and Uncle Vaclav.

Mama wrapped her arms around her sister and commented, “These warnings won’t frighten two brave men, such as Arnold and Bertram.” They both agreed with my mother.

“After fighting the enemy, sleeping out in the dark for months, enduring cold winds, Uncle Vaclav’s jovial pranks promise to be welcome amusement for us,” Bertram declared.

Father was excited that the family was together again, and in the company of Arnold and Bertram.

“Let us celebrate the victory of the Gutthiuda! May our summer festivities begin!” He raised his mug and drank a long draft of mead, to make up for his long absence from home. I settled for a long swig of milk with my aunt and her children.

Mama drank a generous amount of mead herself, feeling content to see her husband and son again. “Here’s to feasting on the midday meal! Let’s eat before the food runs out!” . . . just as my other uncles and aunts arrived with their brood of eight children.

“Oh ho! So you’ll not be saving some food for us, now?” shouted my Uncle Wolfram, as he entered the crowded room.

“What a sad welcome, to see all of you eating up the meal before our very eyes!” commented my third Uncle Reiner, who already looked as though he had eaten a cow, judging by the size of his paunch.

I hurried to serve my cousins portions of food on small platters set on stone seats as they gathered on the floor. The adults sat upon the benches at the large table, once they had grabbed a chunk of meat or the leg of a bird. Our faces were lit by the fire, with stains of grease and butter around our mouths. Crumbs stuck to the small faces of my cousins. I smiled at them, and they smiled back.

“Please help yourselves to anything you like, as long as it’s not my women!” Father said, “and be sure not to make off with sheep tonight, under the pretense of seeking warmth!” as he winked at Arnold and Bertram.

I glanced at them and noticed they were both discreetly stealing glances at me. I wondered what they were thinking. They were very handsome, with their strong, broad shoulders, and thick necks. I felt slight pleasure from their admiration but I was not familiar with them, and thought it would be wise of me to be cautious.

Arnold and Bertram were speaking to Adalwulf by the storage shelves. I returned to the conversation with my aunts, concerning preparations for the summer festival.

“Adalwulf, it has been a long time since we have had such good company and drink,” Arnold remarked.

“Your sister, Ermentrude . . . is she of age to become acquainted through conversation?” Bertram asked Adalwulf, with his head cocked to one side.

“Bertram and I are keenly interested in your sister. She is a beautiful girl. Is she clever? Does she have character?” Arnold wanted to know.

“You will be here long enough to become well acquainted. Ermentrude will be the judge of who she wishes to engage in further conversation,” Adalwulf said.

“Perhaps she will even agree to courtship?” Bertram eagerly suggested.

Adalwulf was surprised by their candidness. He didn’t quite think I was old enough at fifteen, to be courted by his two older friends. He had to think before he answered.

“Aah! Now the truth appears!” he said to his two friends, “You returned home with me just to meet my pretty sister!” He winked an eye at them. “I will agree to your speaking to my sister, only when I am present, you fiends,” as he laughed over a sip of mead. They clinked their mugs in agreement.

Adalwulf hooked his arms with theirs and slowly advanced toward me. He wagged his head sideways at me, which was the signal for me to excuse myself from the group of women and talk to him and his friends. I was nervous about talking to them and answering their questions.

“Adalwulf, do not bother me with your war stories. I want to enjoy myself without stories of bloodshed and mutilations,” I spoke earnestly.

“Ermentrude, I will not fill your head with stories of battle this time. I want to introduce you properly to Arnold and Bertram, since they wish to learn of your esteemed abilities. If you desire to reveal your passions and interests to them, I will not stand in the way, in any manner. What do you think, Ermentrude?”

“Hmmm . . . I suppose it would be agreeable to become further acquainted with them, but not too familiar, as to become improper. You should always be present during our conversations, Adalwulf,” I insisted.

Arnold and Bertram grinned at being allowed to entertain Adalwulf’s sister . . . me! I was uncomfortable, as I had no experience with them. I regarded them as strangers, despite Adalwulf’s familiarity with them. On the other hand, Father knew them and had agreed to their visit here. I thought it would be acceptable to talk to them.

“So, Arnold and Bertram, have you no families to return to after the war? I have never seen you around the Wisla River before. Are you Gutthiuda, or of another tribe? Are your families living near our village?” I thought to bombard them with questions, to determine from their answers, how much I would reveal about myself.

Arnold answered me first. “We are from a Gutthiuda village further up the Wisla. We will travel up the river next week to see them.

Bertram spoke next, “Ermentrude, we heard about your admirable qualities from Adalwulf. Your beauty is far beyond his descriptions of you. When we first saw you, we felt we must become better acquainted.”

My jaw dropped a little. “I am flattered, but I am merely a young girl of fifteen years. What do you want to know about me?”

“We only want to know you better, Ermentrude. What interests you? What are your passions? ” Bertram said, straining his voice over the noise of the family talking.

“I suppose we will have time to become acquainted, soon enough, lovely Ermentrude,” Arnold chimed in. “Let’s visit tomorrow when less family is about.”

Adalwulf seemed surprised at the attention I was receiving from his companions. He wanted me to have a proper suitor, and either of these men would be acceptable to both our father and himself. Adalwulf also knew that I was a free spirit and had no interest in any man, even though I was of age for betrothal.

I was more inclined to wander the land, on horseback, across the Wisla’s lowlands and through the forests of the Carpathian Mountains, than to settle down with a husband. I still had dreams of battling the enemy. I was not willing to stay at home anymore. I was trained with weapons just as Adalwulf was trained at a young age. I could defend myself. All women knew these skills, just as they knew how to sew and cook. I was quite young when I had held my first sword and shield.

My family talked and sang many songs of our ancestors’ brave deeds that night. We listened to stories, that a few of my younger cousins had never heard told before. Their faces flushed with excitement, and their eyes opened wide hearing stories about slaying an enemy. The next day, they would be eager to spar with their weapons.

Arnold and Bertram were shown to a corner bed, to share that night after the festivities. I attempted to sleep in bed with Ava, but I could only think of tomorrow.

Early, as the darkness crept away, I awoke to the sound of voices shouting outside. I listened; I thought I heard a hearty laugh. I noticed sounds of thumping wood and clashing weapons or tools, followed by more shouts and laughter. Being curious, I got out of bed, with my hair a mess, and stepped outside, with a woolen blanket wrapped around me. It was midsummer; it was chilly with a damp fog. Leaving the shelter of the house, I saw that it was beginning to grow light outside. I squinted to see what had caused all the noise. I could only see two pale figures over by the latrine, running around with something in their hands. Perhaps they were playing some strange tactical game with a hammer, sword, or ax? They each continued to utter beastly laughs, moving together, then apart, chasing each other.

Soon, the whole family stood outside, wondering what had disrupted everyone’s sleep. Ava was a bit frightened by the noise and clung to my blanket. Att-a walked toward the two unknown figures, with a sword in his hand, thinking they were intruders. His demeanor changed, when he recognized the two figures, as Arnold and Uncle Vaclav.

“Are you both trying to chase the skoh-sl (evil spirits) away, or awaken them?” Father shouted. They continued their antics, despite a short pause in their attacks on each other. “You both should be ashamed, acting as two wild men waking everyone!”

“We must determine the winner of this challenge, since Vaclav and I are eager to play pranks on each other!” Arnold exclaimed, almost breathless.

“Ja! Arnold thought I was a wild heathen, when he came outside to use the latrine. I leaped off the roof with my ax. He swung a club at me. You should have seen his eyes, when I jumped before him in the dark! I laughed so hard, I . . .” Uncle Vaclav said, as Adalwulf interrupted him.

“You men are so amusing, with only blankets draped around your waists, looking as though you are having the best time,” Adalwulf said. “Arnold, I see you left the house heavily armed.”

“That’s right, my friend! I dislike being attacked by a wild animal with my trousers down in the middle of this darkness and fog. When I saw it was Vaclav, I was determined to scare him in return!”

“Well, don’t go anywhere without your weapons, even in midday. Many dangers await you. You have not bathed in days, so your scent is ripe for predators, my good comrade,” Adalwulf added. Everyone laughed at that comment and returned to the house. Arnold and Uncle Vaclav shook hands and slapped each other on the back.

“Oh, to know Uncle Vaclav is to love him for his pranks,” I said to Ava with a cheery smile upon my face. “I remember when I was younger, Uncle came to our house, and hid behind my bed in the dark, scratching at the wood very quietly, as a small beast; ready to pounce upon me in the middle of the night. I yelled and cried for Att-a to find the beast. When Att-a found Uncle Vaclav there, he swept him out of his hiding place and let me hit him with the broom, all the way to the doorway, as Uncle yelped like a little dog. He is scary, but amusing.”

“I hope Uncle Vaclav never frightens me that way!” Ava noted. “I would tickle him, until he begged for me to stop.”

I hugged her and went into the house to help prepare a breakfast of sausages, bread with butter, and sticky porridge. We had to help with the laundry and feed the animals after breakfast.

At midday, when things had quieted, it seemed the men had nothing to do, except rest and talk amongst themselves; the women tidied up their houses and hung up the clothes to dry in the cool, midsummer breeze. It was Friday, so I was ready for an afternoon of leisure before cooking began again for the festival of the summer solstice. I reclined, with my eyes closed, on a pile of straw near the stalls, where we kept our pigs, cows, sheep, goats, and horses. I loved the smell of the animals nearby. Their familiar bellowing and neighing felt comforting.

“Ah! There you are, Ermentrude. We decided to keep you company,” Adalwulf announced. Arnold and Bertram were beside him. I sat up, startled.

“Oh! You came in suddenly—I wasn’t expecting you. What do you need, Adalwulf and friends?” I asked.

“We were looking for you, so we could talk,” Adalwulf said.

“You mean you want to torture me with endless questions!” I pouted.

“Ne, we just want to get to know you better, Ermentrude,” Bertram explained, “You said you wouldn’t mind.”

“Fine, what do you want to know, that isn’t your business?” I retorted, feeling bothered at the moment .

“For instance, you are fifteen. Have you ever thought of marrying someday?” Arnold inquired.

“Ne, not really. I have thought about marching off to battle with my sword, and perhaps marrying my horse!” I replied with my usual humor. “My wish is to wander about and see all of Middle Earth.”

“Well, you can do all that, er, except marry a a horse, of course!” Adalwulf declared. “You must seriously begin to think of marrying someone, Ermentrude. Our parents cannot afford to feed and clothe you forever.”

“Well, it seems they don’t mind feeding you; you eat more than me! Why haven’t you married, Adalwulf?” I answered, with a smirk.

“If you must know, I have plans to marry next spring . . . to Amalia,” he replied.

“Oh, I didn’t know, Adalwulf. That’s good news! Congratulations on your decision. Have you told Amalia, yet?” I asked.

“I haven’t, yet. As you remember, I was away from home. I am going to propose to her this summer. I will give her a wedding gift of amber beads from the coast. Do you think she will treasure it as a gift of my love?” Adalwulf searched my face for approval.

I smiled and told him, “Amalia will accept your proposal of marriage because she thinks you are quite handsome and brave.” He returned my compliment with a hug. Arnold and Bertram watched, hopeful that I would regard them with such affection someday.

Our conversation continued during the next hour. It was apparent that I had to persuade Arnold and Bertram to give up their thoughts of betrothal to me. I thought them handsome and charming, but dull.

Late in the day, I helped Mama to prepare a simple meal of cheese and bread, when she spoke to me of the day’s events. I told her about Adalwulf’s insistence that I marry one of his friends, Arnold or Bertram. I asked what she thought, before revealing my intentions. She grinned and disclosed that Father had already discussed the matter with her. She also told me that Arnold and Bertram each had a valuable gift for me if I accepted marriage to either of them.

“Your father secretly told me this . . . last night. Isn’t this exciting, Ermentrude? You may choose who you feel is better suited to you. You will marry a strong, handsome, noble man, either way. We have known their families for a long time. They have many cows, sheep, and go . . .” she was suddenly distracted by my tears. “What is the matter, Ermentrude? Surely you must be happy with tears?”

“Mama! How can you insist on my marrying a stranger? I don’t want to marry a stranger! I don’t want to marry anyone! I only think about leaving after the summer festival to help win battles against the enemy tribes. I only think of traveling far away from here. Perhaps, one day I will marry someone—someone I love in my own way,” I said, feeling betrayed.

Mama swallowed her words and turned away from me, as though I had extinguished the fire in her heart and the hope in her eyes. She would not speak to me of these dreams I had for myself. She thought only of her dreams. Did she not deserve little grandchildren running about the house?

She sighed, “Your father will decide what is best for you, Ermentrude.”

I gasped at her words, “Att-a will listen to me, Mama. He knows what is in my heart. I am sorry to disappoint you.” I turned and walked outside to find my father. I would soon learn of his thoughts.

Father was with the horses, speaking to them in quiet tones, soothing them, as they were disturbed by something outside the barn. I entered abruptly and spoke to him.

“Att-a, I must speak with you, please, Att-a.” He could see my tears and sense that I was upset.

“Yes, Ermentrude. You must speak, and I must speak as well . . . of your betrothal to one of your suitors. Have you decided who it will be? Who do you choose to marry?” he asked patiently, knowing that I was upset at being told to marry. “You have the choice of who you want to marry.”

I heaved a sigh in my breast and walked closer. I reached out my arms to embrace him, as I attempted to explain how I felt. His mind was made up.

He replied patiently, saying, “Ermentrude, I know marriage to a stranger is not easy for you, just as it will not be easy for us, when you leave us with a husband. You will learn to appreciate and maybe love the one you decide to wed. That is how it was for your mother.”

I looked up into his eyes and accepted my fate, at least for now. I hugged him again and left, disheartened. I think he was relieved that he didn’t have an argument with me.

“Let us know your decision, daughter! You must decide by summer’s end,” he said.

Turning back, I said, “I see that I have no choice, Att-a, so I will think hard upon this matter. I will tell you of my decision soon,” I assured him. I knew in my heart, what I would choose to do. I sent a message with a slave to my friend, Saskia, who lived in the next village an hour away.

Early next morning, I left home. I took the horse that my father had promised would be mine someday. I rode Brunhilda into the darkness and fog, to meet Saskia. After half an hour’s ride, I met Saskia at the river. We were both determined to live our own adventures.

“Saskia! I am very happy to see you! It was good that you arrived before the light of morning. Did you bring some food and water . . . warm clothing for the cool nights, and your weapons?” I excitedly asked.

“Ja! Of course I brought what is needed. Stop gabbing and ride with me now. We must ride far enough, so our kinsmen will not follow us. We must ride up the river bed, so our tracks cannot be seen. Let’s go, quickly!” Saskia was a fine horse woman and a sincere friend. She always told you what she thought and rarely changed her mind.

We both rode together finding our way through Middle Earth. We would search for a tribe to join, or a band of people going off to battle. We would find someone to love perhaps, but we would know their soul, and they would know our passions. We were sad to leave our homes and kin, but, we thought selfishly . . . only of ourselves.

“Ermentrude, let’s ride until we reach the forest upstream. We will make our breakfast and rest the horses,” Saskia said. The sunlight streamed through the lifting fog. “We must continue to ride, or we will be found and made to return.”

“I am so tired, but I will not fall asleep on Brunhilda.”

“I am so hungry, I could eat Brunhilda!” Saskia laughed. I always appreciated Saskia’s humor, but I quickly said, “No one eats Brunhilda! Not even the wild beasts in the forest.” We rode up the course of the rippling Wisla River, which flowed down from the Carpathian Mountains in the distance.

After several hours, we rested at the edge of a small forest near the Wisla. The great mountains rose above the vast, grassy lowlands. We could see for many miles, down the river from where we came. We unpacked our loaf of bread and cheese, gulped a bit of water with our meal, washed the dust off our faces in the cool river, and rubbed our sore behinds.

“Aaah! It feels wonderful to be off our horses with a bit of food and drink in our bellies, ne?” I said, as I swatted a fly from my brow. “Saskia, would you do me a kind favor?”

“Anything for you, my dear, best friend,” Saskia answered.

“Would you please tie my hair in a knot off my face? My hair gets in my eyes. I did not have time to tie up my hair when I left home,” I said. I was always conscious of my hair no matter where I roamed.

“Well, I didn’t have much time either, so I will first help you, and then you can help me with my tangled hair.” Saskia replied, shaking her reddish blond tresses. We quickly took turns tying each other’s unmanageable locks, for we knew we must ride for many hours before sleeping.

Mounted on our horses again, we traveled through the forest to gain some time lost in navigating the rocky river bed. We rode through a narrow and sparsely populated forest of trees, nothing similar to the dark, endless forests of the Albis (Elbe) River, which had been described by tribes that passed through our villages. We felt safe together with our swords and knives by our side.

Saskia brought an old ax that her mother had found buried years ago. It was probably from the early times when men first roamed the Middle Earth. Saskia thought it would be useful for chopping wood for a warm fire in the evenings. She was skilled in surviving the wilderness.

Her father had taken her along on many hunting trips and to a number of battles. He had no sons, so Saskia was treated as one. She was very independent. I tried to be as good as her, but I lacked some of her skills. She was a fine hunter. I was better suited cooking our meals, although I was a competitive fighter with my weapons.

We each knew many stories from our childhood. We spent the evening telling these stories to entertain ourselves, sitting around the campfire. The tales were of the brave warrior god, one-eyed Wodanaz, and of his wife, Frijjo, who was magical. Punaraz was the son of Wodanaz and Frijjo. Punaraz was known for his thunderous voice, and he wielded a hammer. The gods lived in Asgard, in Middle Earth, and one would have to cross a rainbow to get there. To the north, was Hal-ja, the land of the dead and giants. Another god, Loki could transform into any being, be it a creature or a man. Loki was the father of Hal-ja, the goddess of the dead.

These were the gods we worshipped and to whom we made sacrifices in our sacred groves. We carried their wooden effigies, the bear, the wolf, and the boar, into battle. We prayed to them for strength in battle and relief from floods and famine. They were involved in all aspects of our lives. Wodanaz was the ruler of Valhalla, where the brave warriors went in their afterlife. I hoped to go there in the end, as well.

The next day, we traveled safely past the Vandali people, a fierce tribe who lived upstream from the Gutthiuda. It was one of the tribes that had tried to take back our land long ago. We rode up into the highlands, just below the white-peaked Carpathians.

The summer air here was fresh and cool. That’s where we found a small tribe of people traveling along the upper Wisla. They were the Gepids, from what we learned from them. They were more peaceful than the Vandali, but still mighty in battle. They noticed us riding up behind them and looked startled at first, until they realized we were only two older girls. Our smiles won them over. They trudged slowly along on foot, and by horse and wagon. It was tough moving anywhere because of swampy bog and rocky outcrops on the steeper slopes. We decided to assist them in their journey uphill.

“Do you want us to give you help?” We asked with smiles that generated concern for their hardship. The people replied with warm smiles and nodded. We dismounted and let some children ride up on our horses, as we led them along the wagons. A younger man looked us over and saw that our weapons were not drawn, so he did not seem too concerned for his safety.

The men spoke the words of our tribe—“Gutthiuda?” they asked us. We nodded and walked on, telling them that we were from the Gutthiuda village at the fork of the Wisla River.

We gave the children some of our food, for they looked starved. They rode on our horses, four on each, hungrily shoving morsels of bread and cheese in their mouths. Their mothers raised cups of water for them to drink. The children’s eyes reflected the brightness of the sunny water in the river. They were very polite as they spoke, “Thaoks,” in our Gothic language.

“I wonder where they are going, Saskia?” I whispered.

“Probably returning home, since they live up here,” she answered.

“How do you know?” I asked her quietly.

“I have seen their villages before, hunting with my father. They are fun-loving people. They love to sing and dance in the evenings,” Saskia informed me.

“Maybe we will get to see them perform at their summer festival. Tomorrow night is the summer solstice,” I said.

“Wouldn’t that be thrilling . . . to experience another tribe’s festival?” Saskia said.

We walked on through the afternoon. It was late when we arrived in their village. The women helped us find some warm shelter, for in the mountains—it was still cold at night. Often there were storms that blew in, without notice. We were thankful for the women’s good care.

“I hope someday I can be a good mother to my children,” Saskia revealed. I always wanted little boys and maybe some girls. My sons will be heroes among our tribe. My father will finally have a grandson to take hunting.”

I was stunned that she thought of having a family someday. I thought she would never be remotely interested. I told her that I planned to marry when I was older and wiser . . . when I had seen more of the world. Saskia considered this and spoke wisely, “If you grow old, without the love of a husband, you’ll grow too old for children.”

Again, I was astounded at the thought of growing too old and never being able to have children. I had never thought about the age one had to be to have children. It’s true that some older women had healthy infants, but more than likely, not. Their children were different in their behavior and facial features. Often they became orphans when their older mother or father died. It was the kindness of relatives or tribe that took the children under their roof. I considered this revelation. I learned much from Saskia.

We slept soundly that night in the village of the Gepids. They were peaceful people. We slept until midmorning, when we were awakened by voices at our door. Three older men spoke in Gothic. Saskia and I got up and hurried to the doorway to speak to them.

“Come. The summer solstice has arrived. You must prepare with us, the slaughter of fresh meat for the gods. We must appease Wodanaz, so we will be safe in battle against the warriors who invade our land. We know you have weapons and great skill. Hurry and eat your breakfast. We must leave now for the stables and to the sacred white grove,” said one man with a commanding voice. “The prisoner must be carried to the sacred white grove. He will be sacrificed to Wodanaz. You will watch, as witnesses to his death.”

We swallowed our breakfast, and led our horses from the stable. We tied several goats to our horses, along with an old limping horse, to be led slowly to their demise. The prisoner was led in a wagon by two horses and several people. The whole tribe appeared in their doorways and soon followed up the trail to the sacred white grove, shrouded in fog.

In the grove, were many sacred white trees and wooden stakes, upon which, there were bleached skulls of animals. Huge wooden effigies of the gods, with carvings that displayed their eyes and male or female animal parts, also stood around the sacred grove. The women carried bowls of offerings to Wodanaz and placed them in the boggy mud at the entrance to the grove of sacred white ash trees.

Their priestess stood by a stone altar near the trees, where three eagles looked on with intense stares. One of the eagles shifted its weight and turned its head. It’s gold eyes watched as the animals were slaughtered on the altar and their blood collected in wooden bowls. The priestess chanted sacred words to bless and offer the sacrifice to the gods. Women sliced off the animal’s limbs and hung them in the branches. The carcasses were deposited on the roasting fire, for the tribe would partake of this food in celebration of their life and their enemy’s death. It would transfer Wodanaz’ power to them.

The prisoner was led to a sacred ash tree with the fresh limbs of animals hanging from its branches. On the altar near this tree, the prisoner’s life was solemnly taken, as an offering to our god; the priestess spoke to Wodanaz. The prisoner’s arms were cut off and hung in the tree. Blood seeped from the wounds and drenched the ground below. We were repulsed, but we knew it was necessary for our survival, as Gutthiuda and Gepids.

We chanted and sung songs of Wodanaz’ brave deeds. Later, we feasted upon the roasted meat of goats. The bonfires were lit, left to burn all night and into the next two nights to give strength to the sun. Couples leapt over the bonfires to determine how high their gardens would grow. The three released eagles soared over us for several days. We felt the power of our god, Wodanaz. He would surely protect us from death. Wodanaz would decide who lived or died.

In a week, we would travel to the battleground, into the villages of the enemy, to slaughter again, every man or woman that fought us. We would hold their captured children and women as slaves. We would seize their livestock and food, their treasures and weapons. Our enemy would suffer for their aggressions against the Gepids, our Gothic allies. Saskia and I looked forward to the battles—ones we have seen many times before. We would whoop, and the men would shout and chant, as they chased and hunted their opponents.

“Wodanaz, please protect our warriors—give them power,” we chanted with the other women.

“Wodanaz, mighty lord of death, give us life and victory over those who take our land,” shouted the men, who would soon frighten their enemies. Each of the men’s swords had rune markings etched into the blade. These markings transferred Wodanaz’ power to them with utmost certainty.

At the end of the festival, a great round wheel, tied with straw—representing the sun, was set ablaze at the top of a hill and rolled down the slope to extinguish in the pond below. This signified that the festival of summer was over. We could resume our daily preparations for our journey into war.