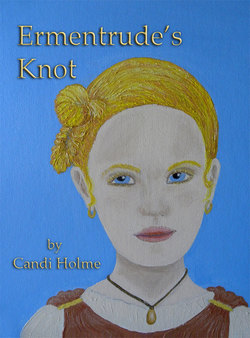

Читать книгу Ermentrude's Knot - Candi J.D. Holme - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter IV Captives

ОглавлениеThe morning came. I opened my eyes to see Saskia sitting on the edge of my bed. She smiled and leaned over to hug me.

“Saskia! You are here! They let you come! I asked Draga if I could see you. I am so happy! What happened to us?”

“Ermentrude, I thought I would never speak your name again! But here you are. I was brought here a while ago by Draga. She seems rather pleasant. What a difference from those brutes who brought us here! Do you know what happened to Anselm and Gerulf? she asked. “Are they here? Do you know?”

“I’m sorry, Saskia, I don’t know what has happened to them. I wish I did. How did we become captives when we had two guards all night?” I questioned.

“I awoke early, in darkness, to see if Erwin and Alfons were still guarding us. I thought they might have fallen asleep. I saw no one guarding our horses and camp. The horses were gone! I rushed over to Anselm’s tent, and found it empty. Gerulf was not in his tent, either. I started to panic, when I thought—where is my knife, and where is my sword? My ax was also missing.” Saskia brushed a hair from my face and continued. “I decided to quietly look around, when I tripped over a rock and fell. As I got up, a strong arm grabbed me around my waist. I kicked and tried to yell, but a hand stifled the sounds from my mouth. I even tried to bite the hand . . . but I missed. As I was being carried away kicking, I did see something behind a boulder. It was a foot. I could only think that our friends were surprised and killed. That frightened me. All I could think about was you, Ermentrude. You were still sleeping in our tent when I left. I prayed that you would be overlooked,” Saskia spoke urgently.

I hugged her and asked, “Saskia, I wonder if anyone survived, besides us? Do you think . . . that Gerulf . . . or Anselm . . . are dead?” I choked down my tears.

“Ermentrude, it must have been a small band of men that took us by surprise, so quietly. Bruno was a big, strong man, and so was Gerulf. It must have taken all their strength to subdue those two brothers. We can only pray to the gods that they are safe. Maybe they left the camp to go hunting early. If so, Gerulf and Anselm, or, someone, will track us to this place. I hope this is what happened, and that they have my weapons—my mother’s ax!” Saskia seemed hopeful. She leaned over to kiss me on my cheek and hugged me for comfort.

“Oh, Saskia, I really hope you are right. Maybe Draga will help us find out what happened to Gerulf and his comrades,” I presumed. “I must ask . . . were you in my room last night? Did you hear me scream?”

“Ja, you said a man was in your room. I heard you screaming, so I ran to your room. He must have left before I came. I never saw him.”

“So, it did happen. I thought I dreamt it. I must find out who he is and avoid him.”

“We’ll keep our eyes open today,” Saskia said.

A young girl, about eight years old, the age of Ava, came to my room to call us to breakfast. We smiled at her and followed her outside to a table with benches. Other people sat there, staring at us, as they ate their meal. We bowed our heads and sat at the end of the table, across from each other. Bowls of food . . . porridge, and bread, were passed to us. We thanked them. The people, servants or slaves, seemed as hesitant to speak, as we were to speak to them. Finally, one woman spoke to a young girl sitting beside her. The others spoke in quiet voices to each other. Saskia and I remained silent. We did not know what the people were saying to each other, but they sounded serious. Maybe they knew about the evil man who had come into my room last night. Could this have happened to them, when they first arrived?

After our breakfast, we were shown what to do around the main house. It seemed to be on a farm . . . a large farm. Saskia and I were told to wash the wooden and metal bowls, utensils, and cooking pots in a kitchen that was similar to my mother’s kitchen. We were told to make bread, as well as sweep the floor of straw, lay down fresh straw, and go outside to help with whatever was needed.

We left the house to see the overseer of the field slaves. I gasped and clutched Saskia’s arm when I saw him. He was the man who had entered my room last night. He spoke to us in a coarse manner.

“So, you are the new wenches—come into slavery, have you? You can expect to be busy here. You can pick weeds the rest of the day. There will be no resting out here. You will get water when you have finished. Get your hoes and get to work, you lazy heathens! When you have earned your meal, you shall have supper. Oh, and you . . . with the knotted hair, expect a visit tonight. Keep your mouth shut, and I’ll go easy on you. Say one word to Draga, and I’ll slit your throat while you sleep,” the man threatened. He turned to Saskia and said, “That goes for you as well! You scratch my itch, and you’ll survive! Tattle, and I’ll bite. Understand?”

We nodded and shivered with anger. We would not accept his conditions. We planned what to do next.

It had been a long, tiring day. Later that evening, when Saskia and I had retired to our rooms, Draga had entered quietly to ask me about my day.

“Ermentrude, you work hard. You. . . ask of your friends. I ask one man . . . took your friend . . . at camp. Man not tell me. He tell me . . . they kill; one of friends . . . blind with . . . knife . . . leave—for bear, or, wolves to eat,” she explained with a sad look in her eyes. My heart and stomach ached for the men she spoke of. Tears spilled down my cheeks onto my tunic. I sighed and tried to speak.

“I must thank you for telling me this, Draga. Did he tell you anything else about the blinded man?” I had hope that Gerulf was still alive. I hoped Draga could understand me.

“Ne. He—say—man . . . in tree, hide, throw ax. He fall, he look up, knife to eyes. They not want he to take revenge,” Draga revealed, “I sorry, I know not more.”

I held my hands up to cover my eyes. I did not understand clearly what Draga had told me, but I understood enough to know that Gerulf was blinded and left to die. His comrades were murdered—left to be devoured by the beasts that wandered the hills. My eyes were wet with tears. I had to let Saskia know that our dear friends were gone—especially Anselm. I had to let her know that soon, Gerulf would be dead, as well. Draga comforted me with her arms held around me. So, that’s why her eyes looked so sad. She had known what had happened to our friends. She didn’t want to tell us. I was glad to know though. It would give me the courage to revenge their deaths and suffering—somehow. Draga left, and I sat down and wept. I thought of how to get back at the cruel men who murdered and tortured the men we had grown to love.

That night, as I waited in bed, the evil man returned to my room. His eyes were dark and his hot breath upon my face made me feel uncomfortable. I breathed shallow breaths, waiting for him to touch me. His hand grabbed my breast. He leaned closer, as his legs climbed on me . . . a beast in heat. Suddenly, he moaned and rolled off me, trying to clutch at something behind him. Saskia withdrew her knife from his back, and we lifted him to the floor. After digging out the straw from my bed, we lifted him and buried him in the bed frame, covering him with straw and linen. He would not be found until the whole farm was searched. I slept in Saskia’s room that night.

“Saskia!” I whispered, as we went to breakfast the next morning. “I found out from Draga. She told me that all the brothers, maybe Anselm, were killed. They found one man who fell out of a tree—I think it might have been Gerulf. He was blinded and left for the wolves,” I hurried to tell her, squeezing her hand quite hard. She sobbed for the loss of Anselm and all the brothers. She imagined their deaths.

“What? How could this happen? They were armed! Oh . . . Wodanaz . . . you must help us revenge their deaths! What murderous heathens those men are . . . to do such a horrible deed! May a great flood spill over their land and drown them all . . . the rats!” Her eyes welled up with tears, and mine filled again. We paused by a stack of hay, to hug each other. Our grieving hearts would never recover from the pain heaving in our chests—oh, the unbearable ache! We could not sit at breakfast with the other slaves this day. We could only cry for our friends and hope that one of them was still alive. A dead man buried in my bed caused me to worry for our safety. We had to escape.

My thoughts were interrupted by a whinny in the distance . . . from a horse. We separated from our hug, sniffed our runny noses, and stared at each other for a moment. Together, we crept over to the open barn, where the animals were kept. I peered inside, to see whether there were any people around. Several horses, some goats, and swine, along with a young boy of ten or eleven years were in the barn. The boy was grooming a horse, speaking to it. He must be a servant or slave, I guessed.

“Should we talk to him to find out if our horses were captured and brought here?” I whispered to Saskia. She nodded her head.

“If we go together, he might help us find our horses . . . or he might tell us to leave!” she said. “We have to try.”

We walked quietly into the barn, carefully looking around for any other person that might object to us being there, but we didn’t see anyone, besides the boy.

Upon seeing our entrance, the boy stopped brushing the horse he was grooming and spoke, “You . . . want to help?” I had forgotten that he probably wouldn’t understand our language. So I attempted to demonstrate what we wanted with my hand language. I gestured with my hands, using voice, and facial expressions, to indicate that:

“We are looking for our horses—did you see two horses come . . . yesterday? Where are these horses, now?” With the final word, I pounded my closed fist on my other open hand. I thought that I was becoming really good at communicating this way.

The boy looked intimidated by us. He probably thought that I had demanded something of him. The boy seemed to capture the meaning a little differently from what I had intended. He smiled weakly and put down the brush, walking over to a storage chest to get two blankets, saddles, and leather stirrups, as he continued to ready the horses for us to ride. Saskia and I smiled at him and curtsied with much appreciation. We mounted the horses and rode away quietly. Once we had left the farm, Saskia and I burst out laughing!

“Can you believe how easy that was? We just rode away, and no one questioned us,” Saskia spouted with joy.

“I think we must keep our voices low and stay off the trail for a while, though. Eventually, someone will come looking for us. We murdered the overseer and stole two horses. We don’t have weapons, other than the small knife you took from the kitchen, nor do we have water and food. We must be careful. Saskia, do you know how to catch food without a weapon?”

“We can use rocks if we are quick. I could try a snare, as well. First, we must ride as fast as the wind, or we will be discovered with stolen horses. We would surely be killed for that, as well as, for escaping and murdering the overseer.” Saskia was always thinking ahead.

“Saskia, should we ride home, so we can get help? We need to find Gerulf, and we cannot do that alone, without weapons and supplies.”

“That’s exactly what I was thinking,” Saskia said. “Great women think alike!”

I smiled at Saskia, as we began our journey over the hillocks, around the lakes, through great rivers, and finally north toward the Wisla, where our families were probably waiting for our return. We stopped one night by a stream. Both of us threw rocks at some small creatures and at some fish, but we failed to hit either animals or fish. So we had no supper that night.