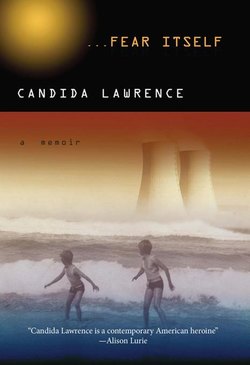

Читать книгу Fear Itself - Candida Lawrence - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SPRING 1946

CHAGRIN FALLS, OHIO

LOS ALAMOS, NEW MEXICO

ОглавлениеWe repack all our belongings in the Olds-mobile in early June, discharged after only nine months. We drive first to Chagrin Falls, Ohio, to visit our new friends, physicist Nat Ellis and his wife, Bette. There, under weeping willows, lying on grass so green it hurts my eyes, we talk hesitantly, for the first time, of atomic weapon development, its dangers, the association of atomic scientists that is forming to raise questions, force answers. Much of the men’s talk is difficult to comprehend, but Bette and I ask for simplification and they rush to explain, finishing each other’s sentences and laughing frequently at how eager they are to flush secrets from their minds. They are in civilian clothes, pale from winter light, but handsome again. We lie on our stomachs in the grass, and when the talk dies down, Bette turns towards Nat, climbs on top of him, hugs, kisses, smears him with red, red lipstick. I sit on my husband and tickle him, and then we play leapfrog over to the fishpond. We take off our shoes and socks and wade in the slimy water. We splash each other.

At breakfast, each man states, carefully, that he will not work ever again in weapon research. And then there is nothing more to say and I am left with a feeling of sadness that stings my eyes. Bette hugs me and promises to write. The men shake hands and quietly say good-bye. We wave our hands out the car windows. I cry for the next thirty miles. He asks why. I say I haven’t the faintest idea. I say maybe it’s because I feel so young and stupid and he is the same age and knows so much more and all that he knows is a pain to him. He squeezes my hand. He says forgetting much of what he’s learned is part of his plan for our future.

His honorable discharge and our medical checkouts restore to us a sense of bodily well-being. We aren’t sick. We make love again, slowly, giving it time and concentration. We enumerate blessings, naming especially his good fortune in not having been out there to be killed in a perhaps just war. We hope the returning soldiers and sailors can slip back into civilian life and forget their experiences. In an adobe eatery near our motel, we clink wine glasses and toast the future: good health, peace, prosperity. We allow ourselves to get a little drunk.

Still, on the long journey back to our friends and families on the California coast, I feel anxious. To myself, I call my condition “cosmic angst”—a wholly grand term that I learned from Nat Ellis, who said, “I am going to use my cosmic angst against those who do not feel it.” “Cosmic” is my favorite word for as large as you can imagine, and “angst”—defined loosely by Nat as “worry”—seems to contain the feeling of nervousness in the choking throat needed to pronounce it, as though I were suffocating in trying to express myself. I often look over at my husband, interrupt my reading to stare at him while he drives, and wonder where he figures in this new feeling. His mother thinks him “fragile,” not in a psychic sense—which would have been beyond her—but in his health, his prospects for remaining alive long enough to enter middle and old age. He has absorbed her worries as his own. I often say “Nonsense!” when he complains of a chill coming on, “It’s…” But I’m not about to give him my new certainty that all over the world something has snapped and that even small children can feel the difference. I don’t know any small children but I worry about them anyway.

We head home by way of Los Alamos to spend a weekend with our friends Pete and Kathy. Pete and I have known each other since childhood, our parents being friends. He is a junior physicist and produced plutonium in a Berkeley lab, like my husband, then was drafted and assigned to Los Alamos after the Bomb. When I was about eleven, we lived across the street from each other and one evening after playing kick-the-can, he kissed me. It was like kissing a baseball. His mother held dancing school in their house, and it was there I learned the tango, the waltz, and Doin’ the Lambeth Walk. Pete is another only child, sole son. He and Kathy have been married a year, and I can’t imagine what she sees in him, she so pert and pretty, he so mother-cocooned.

Kathy is the daughter of a Southern Methodist minister, and I’ve heard from her own mouth tales about how she got her revenge. She surrendered her virginity at eleven (willingly) to her cousin, made out with every available male thereafter, wore purple lipstick, no underpants, low-cut angora sweaters (she cut them down herself) and pointy bras. She smoked and drank anything offered her. I forget how she made her way to UC Berkeley where she met Pete, but he seems an odd choice. He obviously adores her, that petite figure, the dainty gestures and the crude mouth. She is the first woman I’ve known who seems to feel that every sentence should shock, if possible. Pete always sits upright nearby, a silly smile on his face. I believe she is his first woman and so different from his mother he probably believes he’s discovered a new species. He told us once that when Kathy addresses her mother-in-law, she always speaks like the English lit student she was.

So here’s the way it goes in Los Alamos. We are in their bungalow kitchen and Kathy is fixing dinner. And drinks. She is wearing a maternity smock, pink shorts, and her feet are bare. She lifts her glass to the three of us sitting at the kitchen table and says,

“So, now that our precious bomb-makers have made the fuckin’ world safe for bombs, let’s drink to their getting off their asses and reversing direction!”

We praise her tomato aspic salad, served first, and she says,

“Pick an ass, any ass. Oppie-ass. They wipe his behind and worship the stink.”

A cheese-noodle-mushroom casserole: “There’s enough plutonium in this glop to satisfy even their appetite for shit-eating.”

After her third glass of wine, she says, “The fuckin’ baby will arrive glowing blue.” Pete delicately backs up his chair. He says, “No, Kathy…” and invites my husband to join him in chopping wood while the women make iced coffee that we’ll drink on the screened porch. Kathy sips her fourth glass of wine and flings one last sentence at their backs: “It’s eighty-four degrees, but chopping is clean, loud, and the tree’s already dead.”

WOMEN OFTEN WAIT for their men to leave and then unload, but we clean up in silence. She is not glum and puffs contentedly on a cigarette hanging out one side of her mouth while her hands scrub the casserole dish with a coppery ball. I dry. I’m thinking she hasn’t been fair but can’t decide just how to say this. I am afraid of her tongue and even more wary of what seems to be an advanced position on issues I’ve kept fuzzy. I don’t understand the blue glow part, but her condition argues against asking her to explain.

After coffee on the porch swings, she curls up beside Pete and goes to sleep, her head in his lap. He strokes her silky brown hair and looks sappy. We drive out of town the next morning.