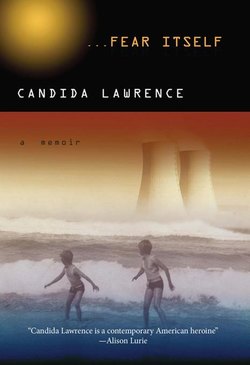

Читать книгу Fear Itself - Candida Lawrence - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1935

ECHO LAKE, THE SIERRAS

ОглавлениеI’m sitting on a large, flat, warm slab of granite high above our mountain cabin. Nearby is Saucer Lake, and far below me is Echo Lake and cabins and kids and parents and outhouses. I can see the lake, the shape curiously unfamiliar, and the motorboats looking like skeeters on the water. I’m not supposed to be up here alone because the adults have rules about hiking. You always have to go with someone, wear a hat, not eat much before or during, drink water sparingly, and chew gum—I forget why. Molly thinks I’m resting in my tent. It’s a rule that you rest after lunch. Another rule is that you can’t go swimming alone and not until two hours after eating. All I want to do is practice my swan dive, but I wouldn’t be doing that today anyway because another rule is that you can’t swim when you have the curse, which I have.

Yesterday was my first day and all of a sudden Molly told me about bleeding every month until I’m old and about sanitary napkins and belts to hold them up and how to dispose of the soiled napkins (wrap them in toilet paper, throw them down the hole in the outhouse, pour lime over them). It seems that my sister has been doing this every month and I never noticed, and it just occurred to me that Molly must do it too. So now there are three of us in our little cabin who bleed and it’s embarrassing for me that I can’t go swimming for four days. Everyone knows I’m devoting my summer to diving and now they’ll know I’m bleeding. The boys will know.

It’s peaceful up here but I’m twitching and trembling and I’m thinking I don’t want it to be a secret. I think it would be a good idea if we all just dribbled blood all over the pine-needle ground and the rocks, spilled the redness into the black waters I dive into. Molly asked me if there were any questions I wanted to ask but I couldn’t think of any. She patted my shoulder and left me alone in the outhouse with the “equipment.”

I lie flat on the warm rock and stare at the few clouds moving slowly across the sky. I wonder how many other girls are on their second day of bleeding and have gone off alone to think about it. This minute, this day, in the desert, in a Paris apartment, in African fields of grass? Did Meg, Amy, Jo and Beth have equipment? No, Molly said she used rags and had to wash them out and it was disgusting. Even so, there’s a population out there thinking thoughts much like mine, I’m sure of it. I wonder if they have to rest after lunch, or even if they have lunch, and can they fix an outboard motor the way I can? I can take the carburetor apart and clean it, fix a cotter pin, get the ratio of gas and oil just right, to say nothing of whizzing through the low-water channel without hitting a single rock.

And now suddenly I’m thinking about the ideas in an outboard motor—the propeller, the gas engine, the rope coiled around the wheel to start it, and I know I could never invent something like that. I can fix it when it’s broken but I don’t understand it any more than I understand why the flashlight I use under the covers at night lights up when you push up the switch, or why the batteries have to go this way and not that way. Last semester I read a whole book on electricity and I could see that if you knew something you might be able to control its power, but still it seemed they were using words like “current” instead of just admitting it was magic, mysterious stuff.

When you think of it, it’s both amazing and discouraging. People, mostly men, are sending talk via telephone across continents, flying everywhere, making radios, looking through lenses at a bacillus that causes TB, designing “equipment” for me, then making up the language that explains it all. And I’m imagining them in all their suits, in their buildings, with their tables and chairs and telephones, in their factories with noisy machinery producing more machinery and tiny parts just the right size and shape. I know I could never take part in all this rampaging invention. Two summers ago Daddy built a whole bedroom onto the cabin and I helped him. He built me my own tool chest with my name etched on top in copper nail-heads. I did what he told me to do. I pounded a nail where he said to and fastened hundreds of shingles. But I wondered every day how he knew what to do each moment. I mean he’s a newspaper columnist and yet seemed to know what would hold up what and why. Me, I might have started with the roof, built it on the ground and raised it somehow later.

People tell me I’m smart. I get As in school. But I know there’s buzzing, brilliant thought inside human beings, and all over the world people are learning things while I lie on this rock. Somehow I’m not part of it. The most I can do is think about it, wonder if we are all alone in the universe inventing and trying to understand. If we are alone and what Daddy says is true, that there’s no God directing us, then it seems so brave to be making roads, accordions, cotter pins, buttons, zippers, jeans with pockets, tennies, sanitary napkins and belts with a metal doohickey to hold them up, and at least five different brands of underarm deodorant. Chewing gum.

I sit up and take my green package of spearmint gum out of my jeans pocket with the brass rivets (why?) and stare at it. There’s an outer wrap and inside are five pieces of gum, each wrapped in green paper with lettering on it, and inside is the gum enfolded in tin-foil. This gum has come to me by boat (the delivery boy is real cute) from the store at the end of the lake. Molly writes an order each day and the next day he delivers everything in person. He has to carry the grocery box up the hill to our cabin. In Berkeley, I can buy spearmint lots of places, and once I asked a visitor to the house if you could buy this same gum in Paris. Yep. This inventing, packaging, selling, traveling of gum is much more amazing to me than the occasional fossil lizard print I find in granite up here above the cabin. The lizard doesn’t have a clue about becoming a fossil, but some human mind wants to be able to get spearmint to my mountain cabin in the summertime. I mean, this all started in one person’s head. He (it’s surely a man) knew that people like to chew, and he invented a substance that wouldn’t stick to your teeth or poison you if you swallowed it; then another person made a machine that formed it into thin rectangular shapes and wrapped paper around them; then someone else figured out how to roll it, fly it, float it all over the world into stores and homes. Amazing.

All these thoughts about people (men) all over the world inventing and manufacturing and selling are giving me a headache and I lie down again. I feel there should be Someone in control, to guide all this busy-ness, and it seems mighty strange that we’re all alone in the universe, the only creatures inventing gum, and it’s all an accident, as Daddy has said. He’s cheerful about the idea of accident. But sometimes he gets gloomy and tells me that human beings also thought up property and God and nations and invented weapons to kill each other when they fight about these things. He was an ambulance driver in the First World War but he doesn’t like to talk about it. Molly says he picked up bloody arms and legs and bodies for two years and was gassed. Someone invented gas.

I know I’ll never invent anything, and if that’s so, what am I going to do with the rest of my life? Especially the times of leak and wearing equipment.