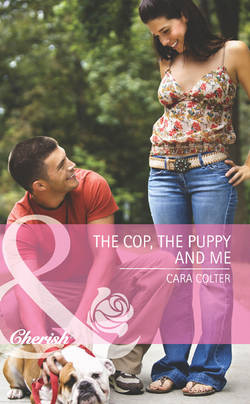

Читать книгу The Cop, the Puppy and Me - Cara Colter - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеOFFICER Oliver Sullivan looked at Sarah’s extended hand, clearly annoyed at her effort to make some kind of contact with him.

She knew he debated just walking away now that he had delivered his unfriendly message.

But he didn’t. With palpable reluctance, he accepted her hand, and his shake was brief and hard. She kept her face impassive at the jolt that surged, instantaneously, from her fingertips to her elbow. It would be easy to think of rough whiskers scraping a soft cheek, the smell of skin out of the shower.

Easy, too, to feel the tiniest little thrill that her life had had this unexpected moment thrust into it.

Sarah reminded herself, sternly, that her life was full and rich and complete.

She had inherited her grandmother’s house in this postcard-pretty town. With it had come a business that provided her a livelihood and that had pulled her back from the brink of despair when her engagement had ended.

Kettle Bend had given her something she had not thought she would ever have again, and that she now could appreciate as that rarest of commodities: contentment.

Okay, in her more honest moments, Sarah knew it was not complete contentment. Sometimes, she felt a little stir of restlessness, a longing for her old life. Not her romance with Michael Talbot. No, sir, she was so over her fiancé’s betrayal of her trust, so over him.

No, it was elements of her old life as a writer on the popular New York–based Today’s Baby magazine that created that nebulous longing, that called to her. She had regularly met and interviewed new celebrity moms and dads, been invited to glamorous events, been a sought-after guest at store openings and other events. She had loved being creative.

A man like the one who stood in front of her posed a danger. He could turn a small longing for something—excitement, fulfillment—into a complete catastrophe.

Sarah reminded herself, sternly and firmly, that she had already found a solution for her nebulous longings; she was going to chase away her restlessness with a new challenge, a huge one that would occupy her completely. Her new commitment was going to be to the little community that was fading around her.

Her newfound efforts at contentment relied on getting this town back to the way she remembered it being during her childhood summers spent here: vital, the streets overflowing with seasonal visitors, a feeling of endless summer, a hopeful vibrancy in the air.

So, handshake completed, Sarah crossed her arms over her chest, a thin defense against some dark promise—or maybe threat—that swirled like electricity in the air around him.

She wanted him to think she was not rattled.

“I have a great plan for Kettle Bend,” she told him. She had interviewed some of the most sought-after people in the world. She would not be intimidated by him. “And you can help make it happen.”

He regarded her long and hard, and then the tiniest of smiles tickled the corner of that sinfully sensuous mouth.

She thought she had him. Then …

“No,” he said. Simple. Firm. Unshakable, the smile gone from the corner of that mouth as if it had never been.

“But you haven’t even heard what I have to say!” Sarah sputtered indignantly.

He actually seemed to consider that for a moment, though his deeply weary sigh was not exactly encouraging.

“Okay,” he said after a moment, those dark eyes shielded, unreadable. “Spit it out.”

Spit it out? As an invitation to communication, it was somewhat lacking. On the other hand, at least he wasn’t walking away. Yet. But his body language indicated the thread that held him here, in her yard, was thin.

“The rescue of the dog was incredible. So courageous.”

He failed to look flattered, seemed to be leaning a little more toward the exit, so she rushed on. “I’ve seen it on the internet.”

His expression darkened even more—if that was possible—so she didn’t add that she had watched it more than a dozen times, feeling foolishly compelled to watch it again and again for reasons she didn’t quite understand.

But she did understand that she was not the only one. The video had captured hearts around the world. As she saw it, the fact he was standing in her yard meant that she had an opportunity to capitalize on that magic ingredient that was drawing people by the thousands to that video.

“I know you haven’t been in Kettle Bend very long,” Sarah continued. “Didn’t you know how cold that water was going to be?”

“If I had known how cold that water was going to be, I would have never jumped in.”

That was the kind of answer that wouldn’t work at all in the event she could talk him into being a participant in her plan to use his newfound notoriety to publicize the town.

Though that possibility seemed more unlikely by the second.

At least he was talking, and not walking.

“You must love dogs,” she said, trying, with growing desperation, to find a chink in all that armor.

He didn’t answer her, though his chest filled as he drew in a long breath. He ran an impatient hand through the thick, crisp silk of his dark hair.

“What do you want from me?”

Her eyes followed the movement of his hand through his hair, and for a moment the sensation of what she really wanted from him nearly swamped her.

Sarah shook it off, an unwanted weakness.

“Your fifteen minutes of fame could be very beneficial to this town,” she said, trying, valiantly, and not entirely successfully, not to wonder how his hair would feel beneath her fingertips.

“Whether I like it or not,” he commented dryly.

“What’s not to like? A few interviews with carefully chosen sources. It would take just the smallest amount of your time,” she pressed persuasively.

His look of impatience deepened, and now annoyance layered on top of it. Really, such a sour expression should have made him much less good-looking!

But it didn’t.

Still, she tried to focus on the fact that he was still standing here, giving her a chance. Once she explained it all to him, he couldn’t help but get on board!

“Do you know what Summer Fest is?” she asked him.

“No. But it sounds perfectly nauseating.”

She felt her confidence falter and covered it by glaring at him. Sarah decided cynical was just his default reaction. Who could possibly have anything against summer? Or a festival?

Sarah plunged ahead. “It’s a festival for the first four days of July. It starts with a parade and ends with the Fourth of July fireworks. It used to kick off the summer season here in Kettle Bend. It used to set the tone for the whole summer.”

She waited for him to ask what had happened, but he only looked bored, raising an eyebrow at her.

“It was canceled, five years ago. The cancellation has been just one more thing that has contributed to Kettle Bend fading away, losing its vibrancy, like a favorite old couch that needs recovering. It’s not the same place I used to visit as a child.”

“Visit?” It rattled her that he seemed not to be showing the slightest interest in a single word she said, but he picked up on that immediately. “So you’re not a local, either?”

Either. A bond between them. Play it.

“No, I grew up in New York. But my mother was from here, originally. I used to spend summers. And where are you from? What brings you to Kettle Bend?”

“Momentary insanity,” he muttered.

He certainly wasn’t giving anything away, but he wasn’t walking away, either, so Sarah prattled on, trying to engage him. “This is my grandmother’s house. She left it to me when she died. Along with her jam business. Jelly Jeans and Jammies. You might have heard of it. It’s very popular around town.”

Sarah was not sure she had engaged him. His expression was impossible to read. She had felt encouraged that he showed a slight interest in her. Now, she was suspicious. Sullivan was one of those men who found out things about people, all the while revealing nothing of himself.

“Look, Miss McDougall—”

She noticed he did not use her first name, and knew, despite that brief show of interest, he was keeping his distance from her in every way he could.

“—not that any of this has anything to do with me, but nothing feels or looks the same to an adult as it does to a child.”

How had he managed, in a single line, to make her feel hopelessly naive, as if she was chasing something that didn’t exist?

What if he was right?

Damn him. That’s what these brimming-with-confidence-and-cynicism men did. Made everyone doubt themselves. Their hopes and dreams.

Well, she wasn’t giving her hopes and dreams into the care of another man. Michael Talbot had already taught her that lesson, thank you very much.

When she’d first heard the rumor about Mike, her fiancé and editor in chief of Today’s Baby, and a flirty little freelancer named Trina, Sarah had refused to believe it. But then she had seen them together in a café, something too cozy about the way they were leaning into each other to confirm what she wanted to believe, that Mike and Trina’s relationship was strictly business.

Her dreams of a nice little house, filled with babies of her own, had been dashed in a flash.

No accusation, just, I saw you and Trina today.

The look of shame that had crossed Mike’s face had said it all, without him saying a single word.

Now, Sarah had a replacement dream, so much safer. A town to revitalize.

“Yes, it does have something to do with you!”

“I don’t see how.”

“Because I’ve been put in charge of Summer Fest. I’ve been given one chance to bring it back, to prove how good it is for this town,” she explained.

“Good luck with that.”

“I’ve got no budget for promotion. But I bet your phone has been ringing off the hook since the clip of the rescue was shown on the national evening news.” She read the answer in his face. “The A.M. Show, Good Night, America, The Way We See It, Morning Chat with Barb—they’re all calling you, aren’t they?”

His arms had now folded across the immenseness of his chest, and he was rocking back on his heels, watching her with narrowed eyes.

“They’re begging you for a follow-up,” she guessed. She wasn’t the only one who had been able to see that this man and that dog would make good television.

“You’ll be happy to know I’m not answering their calls, either,” he said dryly.

“I am not happy to know that! If you could just say yes to a few interviews and mention the town and Summer Fest. If you could just say how wonderful Kettle Bend is and invite everybody to come for July 1. You could tell them that you’re going to be the grand marshal of the parade!”

It had all come out in a blurt.

“The grand marshal of the parade,” he repeated, stunned.

She probably should have left that part until later. But then she realized, shocked, he had not repeated his out-and-out no.

He seemed to realize it, too. “No,” he said flatly.

She rushed on as if he hadn’t spoken. “I don’t have a hope of reaching millions of people with no publicity budget. But, Oli—Mr.—Officer Sullivan—you do. You could single-handedly bring Summer Fest back to Kettle Bend!”

“No,” he said again, no hesitation this time.

“There is more to being a cop in a small town than arresting poor old Henrietta Delafield for stealing lipsticks from the Kettle Mug and Drug.”

“Mug and Drug,” he repeated dryly, “that sounds like my old beat in Detroit.”

Despite the stoniness of his expression, Sarah allowed herself to feel the smallest stirring of hope. He had a sense of humor! And, he had finally revealed something about himself. He was starting to care for his new town, despite that hard-bitten exterior.

She beamed at him.

He backed away from her.

“Let me think about it,” he said with such patent insincerity she could have wept.

Sarah saw it for what it was, an escape mechanism. He was slipping away from her. She had been so sure, all this time, when she’d hounded him with message after message, that when he actually heard her brilliant idea, when he knew how good it would be for the town, he would want to do it.

“There’s no time to think,” she said. “You’re the hot topic now.” She hesitated. “Officer Sullivan, I’m begging you.”

“I don’t like being impulsive.” His tone made it evident he scorned being the hot topic and was unmoved by begging.

“But you jumped in the river after that dog. Does it get more impulsive than that?”

“A momentary lapse,” he said brusquely. “I said I’ll think about it.”

“That means no,” she said, desolately.

“Okay, then, no.”

There was something about the set of his shoulders, the line around his mouth, the look in his eyes that he had made up his mind absolutely. He wasn’t ever going to think about it, and he wasn’t ever going to change his mind. She could talk until she was blue in the face, leave four thousand more messages on his voice mail, go to his boss again.

But his mind was made up. Like the wall in his eyes, it would be easier to climb Everest than to change it.

“Excuse me,” she said tautly. She bent and picked up her rhubarb, as if it could provide some kind of shield against him, and then shoved by him. She headed for the back door of her house before she did the unthinkable.

You did not cry in front of a man as hard-hearted as that one.

Something in his face, as she glanced back, made her feel as if her disappointment was transparent to him. She was all done being vulnerable. Had she begged? She hoped she hadn’t begged!

“You should try the Jelly Jeans and Jammies Crabbies Jelly,” she shot over her shoulder at him. “It’s made out of crab apples. My grandmother swore it was a cure for crankiness.”

She opened her back screen door and let it slam behind her. The back door led into a small vestibule and then her kitchen.

She was greeted by the sharp tang of the batch of rhubarb jam she had made yesterday. Every counter and every surface in the entire kitchen was covered with the rhubarb she needed to make more jam today.

Because this was the time of year her grandmother always made her Spring Fling jam, which she had claimed brought a feeling of friskiness, cured the sourness of old heartaches and brought new hope.

But given the conversation she had just had, and looking at the sticky messes that remained from yesterday, and the mountains of rhubarb that needed to be dealt with today, hope was not exactly what Sarah felt.

And she certainly did not want to think of all the connotations friskiness could have after meeting a man like that one!

Seeing no counter space left, she dumped her rhubarb on the floor and surveyed her kitchen.

All this rhubarb had to be washed. Some of it had already gotten tough and would have to be peeled. It had to be chopped and then cooked, along with all the other top secret ingredients, in a pot so huge Sarah wondered if her grandmother could have possibly acquired it from cannibals. Then, she had to prepare the jars and the labels. Then finally deliver the finished product to all her grandmother’s faithful customers.

She felt exhausted just thinking about it. An unguarded thought crept in.

Was this the life she really wanted?

Her grandmother had run this little business until she was eighty-seven years old. She had never seemed overwhelmed by it. Or tired.

Sarah realized she was just having an off moment in her new life.

That was the problem with a man like Oliver Sullivan putting in a surprise appearance in your backyard.

It made you question the kind of life you really wanted.

It made you wonder if there were some kinds of lonely no amount of activity—or devotion to a cause—could ever fill.

Annoyed with herself, Sarah stepped over the rhubarb to the cabinet where she kept her telephone book.

Okay. He wasn’t going to help her. It was probably a good thing. She had to look at the bright side. Her life would have tangled a bit too much with his had he agreed to use his newfound fame to the good of the town.

She could do it herself.

“WGIV Radio, how can I direct your call?”

“Tally Hukas, please.”

After she hung up from talking to Tally, Sarah wondered why she felt the tiniest little tickle of guilt. It was not her job to protect Officer Oliver Sullivan from his own nastiness.

“And so, folks,” Sarah’s voice came over the radio, in that cheerful tone, “if you can spare some time to help our resurrected Summer Fest be the best ever, give me a call. Remember, Kettle Bend needs you!”

Sullivan snapped off the radio.

He had been so right in his assessment of Sarah McDougall: she was trouble.

This time, she hadn’t gone to his boss. Oh, no, she’d gone to the whole town as a special guest on the Tally Hukas radio show, locally produced here in Kettle Bend. She’d lost no time doing it, either. He’d been at her house only yesterday.

Despite that wholesome, wouldn’t-hurt-a-flea look of hers, Sarah had lost no time in throwing him under the bus. Announcing to the whole town how she’d had this bright idea to promote the summer festival—namely him—and he’d said no.

Ah, well, the thing she didn’t get was that he didn’t care if he was the town villain. He would actually be more comfortable in that role than the one she wanted him to play!

The thing he didn’t get was how he had thought about her long after he’d left her house yesterday. Unless he was mistaken, there had been tears, three seconds from being shed, sparkling in her eyes when she had pushed by him.

But this was something she should know when she was trying to find a town hero: an unlikely choice was a man unmoved by tears. In his line of work, he’d seen way too many of them: following a knock on the door in the middle of the night; following a confession, outpourings of remorse; following that moment when he presented what he had, and the noose closed. He had them. No escape.

If you didn’t harden your heart to it all, you would drown in other people’s tragedy.

He’d had to hurt Sarah. No choice. It was the only way to get someone like her to back off. Still, hearing her voice over the radio, he’d tried to stir himself to annoyance.

He was reluctant to admit it was actually something else her husky tone caused in him.

A faint longing. The same faint longing he had felt on her porch and when the scent from her kitchen had tickled his nose.

What was that?

Rest.

Sheesh, he was a cop in a teeny tiny town. How much more restful could it get?

Besides, in his experience, relationships weren’t restful. That was the last thing they were! Full of ups and downs, and ins and outs, and highs and lows.

Sullivan had been married once, briefly. It had not survived the grueling demands of his rookie year on the homicide squad. The final straw had been someone inconveniently getting themselves killed when he was supposed to be at his wife’s sister’s wedding.

He’d come home to an apartment emptied of all her belongings and most of his.

What had he felt at that moment?

Relief.

A sense that now, finally, he could truly give one hundred percent to the career that was more than a job. An obsession. Finding the bad guy possessed him. It wasn’t a time clock and a paycheck. It was a life’s mission.

He started, suddenly realizing it was that little troublemaker who had triggered these thoughts about relationships!

He was happy when his phone rang, so he didn’t have to contemplate what—if—that meant something worrisome.

Besides, his discipline was legendary—as was his comfortably solitary lifestyle—and he was not thinking of Sarah McDougall in terms of the “R” word. He refused.

He glanced at the caller ID window.

His boss. That hadn’t taken long. Sullivan debated not answering, but saw no purpose in putting off the inevitable.

He held the phone away from his ear so the volume of his chief’s displeasure didn’t deafen him.

“Yes, sir, I got it. I’m cleaning all the cars.”

He held the phone away from his ear again. “Yeah. I got it. I’m on Henrietta Delafield duty. Every single time. Yes, sir.”

He listened again. “I’m sure you will call me back if you think of anything else. I’m looking forward to it. No, sir. I’m not being sarcastic. Drunk tank duty, too. Got it.”

Sullivan extricated himself from the call before the chief thought of any more ways to make his life miserable.

He got out of his car. Through the open screen door of Della’s house—a house so like Sarah’s it should have spooked him—he could hear his nephews, Jet, four, and Ralf, eighteen and half months, running wild. He climbed the steps, and tugged the door.

Unlocked.

He went inside and stepped over an overturned basket of laundry and a plastic tricycle. His sister had once been a total neat freak, her need for order triggered by the death of their parents, just as it had triggered his need for control.

He supposed that meant the mess was a good thing, and he was happy for her, moving on, having a normal life, despite it all.

Sullivan found his sister in her kitchen. The two boys pushed by him, first Jet at a dead run, chortling, tormenting Ralf by holding Ralf’s teddy bear high out of his brother’s reach. Ralf toddled after him, determined, not understanding the futility of his determination was fueling his brother’s glee.

Della started when she turned from a cookie sheet, still steaming from the oven, and saw Sullivan standing in her kitchen door well. “You scared me.”

“You told me to come at five. For dinner.”

“I lost track of time.”

“You’re lucky it was me. You should lock the door,” he told her.

She gave him a look that in no way appreciated his brotherly concern for her. In fact, her look left him in no doubt that she had tuned into the Tally Hukas show for the afternoon.

“All Sarah McDougall is trying to do is help the town,” Della said accusingly.

Jet raced by, cackling, toy high. Sullivan snagged it from him, and gave it to Ralf. Blessedly, the decibel level was instantly reduced to something that would not cause permanent damage to the human ear.

Sullivan’s eyes caught on a neatly bagged package of chocolate chip cookies on the counter. His sister usually sent him home with a goodie bag after she provided him with a home-cooked meal.

“Are those for me?” he asked hopefully, hoping she would take the hint that he didn’t want to talk about Sarah McDougall.

His sister had never been one to take hints.

“Not now, they aren’t,” she said sharply.

“Come on, Della. The chief is already punishing me,” he groaned.

“How?” she said, skeptical, apparently, that the chief could come up with a suitable enough punishment for Sullivan refusing to do his part to revitalize the town.

“Let’s just say it looks like there’s a lot of puke in my future.”

“Humph.” She was a woman who dealt with puke on a nearly daily basis. She was not impressed. She took the bagged cookies and put them out of sight. “I’m going to donate these to the bake sale in support of Summer Fest.”

“Come on, Della.”

“No, you come on. Kettle Bend is your new home. Sarah’s right. It needs something. People to care. Everyone’s so selfish. Me. Me. Me. Indifferent to their larger world. What happened to Kennedy? Think not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country?”

“We’re talking about a summer festival, not the future of our nation,” he reminded her, but he felt the smallest niggle of something astonishing. Was it guilt?

“We’re talking about an attitude! Change starts small!”

His sister was given to these rants now that she had children and she felt responsible for making good citizens of the world.

Casting a glance at Jet, who was using sweet talk to rewin his brother’s trust and therefore get close to Bubba the bear, Sullivan saw it as a monumental task she had undertaken. With a crow of delight, Jet took the bear. She obviously had some way to go.

If she was going to work on Sullivan, too, her mission was definitely doomed.

“Why on earth wouldn’t you do a few interviews if it would help the town out?” Della pressed him.

“I’m not convinced four days of summer merriment will help the town out,” he said patiently. “I haven’t been here long, but it seems to me what Kettle Bend needs is jobs.”

“At least Summer Fest is an effort,” Della said stubbornly. “It would bring in people and money.”

“Temporarily.”

“It’s better than nothing. And one person acting on an idea might lead other people to action.”

Sullivan considered his sister’s words and the earnest look on her face. Had he been too quick to say no? Strangely, the chief going after him had not even begun to change his mind. But his sister looking at him with disapproval was something else.

It was also the wrong time to remember the tears sparkling behind Sarah McDougall’s astonishing eyes.

But that’s what he thought of.

“I don’t like dealing with the press,” he said finally. “They always manage to twist what you say. After the Algard case, if I never do another interview again it will be too soon.”

Something shifted in his sister’s face as he referred to the case that had finished him as a detective. Maybe even as a human being.

At any other time he might have taken advantage of her sympathy to get hold of those cookies. But it was suddenly there between them, the darkness that he had seen that separated him from this world of cookies and children’s laughter that she inhabited.

They had faced the darkness, together, once before. Their parents had been murdered in a case of mistaken identity.

Della had been the one who had held what remained of their family—her and him—together.

She was the one who had kept him on the right track when it would have been so easy to let everything fall apart.

Only then, when she had made sure he finished school, had she chosen to flee her former life, the big city, the ugliness of human lives lost to violence.

And what had he done? Immersed himself in it.

“How could they twist what you had to say about saving a dog?” she asked, but her voice was softer.

“I don’t present well,” he said. “I come across as cold. Heartless.”

“No, you don’t.” But she said it with a trace of doubtfulness.

“It’s going to come out that I don’t even like dogs.”

“So you’ll come across as a guy who cares only about himself. Self-centered,” she concluded.

“Colossally,” he agreed.

“One hundred percent pure guy.”

They both laughed, her reluctantly, but still coming around. Not enough to take the cookies out of the cupboard, though. He made a little bet with himself that he’d have those cookies by the time he left here.

Wouldn’t that surprise the troublemaker? That he could be charming if he chose to be?

There it was. He was thinking about her again. And he didn’t like it one little bit. Not one.

“You should think about it,” his sister persisted.

It occurred to him that if he dealt with the press, his life would be uncomfortable for a few minutes.

If he didn’t appease his sister—and his boss—his life could be miserable for a lot longer than that.

“I think,” Della said, having given him ten seconds or so to think about it, “that you should say yes.”

“For the good of the town,” he said a little sourly.

“For your own good, too.”

There was something about his sister that always required him to be a better man. And then there was a truth that she, and she alone, knew.

He would do anything for her.

Yet she never took advantage of that. She rarely asked him for anything.

Sullivan sighed heavily. He had a feeling he was being pushed in a direction that he did not want to go in.

At all.