Читать книгу Sporting Blood - Carlos Acevedo - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Last Goodbye THE RIVALRY BETWEEN ROBERTO DURÁN AND ESTEBAN DEJESÚS

ОглавлениеHe came a long way to see his nemesis, Esteban de Jesús, in his dying days, out to Río Piedras and to a converted milk factory where the malarial sunlight filtered in through grimy windows overlooking sickbed after sickbed. Now wraithlike, 90 pounds, and seeking solace from a future afterlife, de Jesús had been an addict, a killer, a convict, one of the top lightweights in the world, and, for a little while at least, a national hero, the first man ever to beat Roberto Durán.

◆ ◆ ◆

With José Torres retired and Carlos Ortiz, the gifted ex-champion whose prime began during the West Side Story–era, nearing the end of a creaky comeback, New York City was ready for another Puerto Rican star. In 1972, Esteban de Jesús, born in hardscrabble Carolina, Puerto Rico, debuted at the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden, stopping George Foster in eight rounds. A stablemate of Wilfred Benitez and trained by Gregorio Benitez, de Jesús was a precise counterpuncher with a ruinous left hook and enough dark secrets to last a lifetime. After building a record of 33-1, de Jesús, already dabbling in the nightlife, set his sights on bigger targets—and the temptations that often accompany such ambition. In New York City he had impressed the afición with his sharpshooting skills, but not many believed he would be a threat to young Roberto Durán, the recently crowned lightweight champion stalking greatness.

If New York City was impressed by de Jesús, it was wonderstruck by Durán, who coldcocked Benny Huertas in his Madison Square Garden debut in September 1971 and less than a year later trampled stylish Ken Buchanan for the lightweight championship of the world. Even after building up an insurmountable lead on the scorecards, Durán could not resist his own malicious nature. A split-second after the bell ending the thirteenth round, “Hands of Stone” buried a shot below the belt that left Buchanan writhing on the canvas in agony. Poor Buchanan was ruled unable to continue, and Durán was declared the TKO winner, beginning a reign of terror that would last for the rest of the decade. Brash, bold, and brutish, Durán reveled in his reputation for savagery.

Durán, born in 1951, was too old to have benefited from the social programs of Omar Torrijos, the Panamanian strongman who seized power in 1968. As a child, he hustled around on the dusty streets of El Chorrillo, a Panama City slum that could have doubled as the setting for a Graham Greene novel. For the rest of his life, Durán would be hungry—for money, for women, for celebrity, for combat. In the years to come, he would kayo a woman who charged him after a fight, brawl with opposing trainers during gym sessions, turn press conferences into impromptu melees, and publicly greet Juanita Leonard—married to Sugar Ray, boxing royalty in his heyday—with a middle finger. Most infamously, perhaps, Durán chilled a national audience when he spoke disdainfully about Ray Lampkin, still in distress and soon to be carried out of the ring on a stretcher after Durán had nearly decapitated him with a wrecking ball hook. “I was not in my best condition,” he told a live television audience. “Today I sent him to the hospital. Next time I will send him to the morgue.” But winning the title had given Durán a chance to satiate some of his pangs, and his gluttony would cost him the next time he fought in Manhattan.

Because Durán and de Jesús both had reputations in New York City, where boxing-mad Latinos supported their countrymen as a matter of national pride, a matchup between them was inevitable. They met in a nontitle scrap on November 17, 1972, before a partisan crowd of 9,144. Less than three weeks earlier, de Jesús had scored a ten-round decision over journeyman Don McClendon in San Juan. Now, for $10,000, de Jesús was about to headline Madison Square Garden—still the fight capital of the world—against a rampaging lightweight with unlimited potential.

What was supposed to be a mere distraction from carousing turned into a nightmare for Durán within thirty seconds of the opening bell, when de Jesús landed a snapping right hand that stung him and followed up with a sweeping left hook that nailed Durán flush on the jaw. Stunned, Durán crashed to the mat for the first time in his career. When referee Arthur Mercante completed the mandatory eight-count, Durán dove into the fray again, but he could never claw his way back into the fight.

By feinting and making himself a moving target, de Jesús kept Durán off-balance from round to round, peppering the future legend with jabs, hooks, and the occasional cross. At the sound of the final bell, a disgusted Durán turned away from de Jesús with a defiant gesture of his glove. The unanimous decision went to Esteban de Jesús.

Over-the-weight fights against top contenders were holdovers from the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, and Durán manager Carlos Eleta continued the tradition by denying de Jesús an immediate rematch for the title. “After that fight, we went with [trainer] Ray Arcel to a restaurant and Durán was crying,” Eleta told Christian Giudice, author of Hands of Stone. “I told him you don't win the fight in the ring but in training. . . . He wanted the rematch immediately, but I postponed that fight so that he could get out of this feeling. I waited until he was ready and then I told him that he would fight de Jesús again.” Years later, Freddie Brown, who co-trained Durán alongside Ray Arcel, broke down the upset succinctly to Sports Illustrated. “He had just won the title and he was having a lot of fun celebrating. He didn't take de Jesús seriously. It didn't mean anything to him. He came to New York to play.”

After scoring the biggest win of his career, de Jesús went on to post a pair of decisions over contender Ray Lampkin and a knockout over former super-lightweight champion Alfonso “Peppermint” Frazer. Durán, meanwhile, released his raw fury in successful title defenses against Jimmy Robertson, Hector Thompson, and Guts Ishimatsu. It took a career-high payday of $125,000 to lure him into a rematch against de Jesús—this time in Panama.

On March 16, 1974, de Jesús and Durán squared off before nearly sixteen thousand spectators at the Gimnasio Nuevo Panama in Panama City, where the dry season guaranteed temperatures of over one hundred degrees at ringside. After a grueling struggle to make weight, de Jesús was so drained that Gregorio Benitez tried to postpone the fight under the pretext of a cut de Jesús suffered in sparring. A $40,000 purse convinced de Jesús to enter the ring under unfavorable circumstances. For his part, Durán was training harder than ever before. Not only was he scheduled to face the only man who had ever beaten him, he was also worried about supernatural forces. Even for boxing, with its near-surrealist air, such a concern seemed beyond the pale. According to Christian Giudice, de Jesús had gathered warlocks in his camp in order to hex Durán.

If de Jesús was worried about the inferno-like conditions, he seemed oblivious to them when the opening bell rang. Both men forced a torrid pace in the dizzying heat. Durán, well prepared for his only conqueror, fought with the trademark frenetic style he had been unable to muster in the first bout. Still, de Jesús seemed ready for the onslaught, and for the second time in as many fights, he toppled Durán with a lashing hook barely a minute into the first round. For Durán, who jumped to his feet quickly, the possibility of having been the victim of bad juju must have seemed all too real as he took the mandatory eight-count.

From that point on, Durán and de Jesús—the best lightweights in the world—warred toe-to-toe until one of them began to wilt. It was de Jesús who succumbed. With less than a minute remaining in the seventh round, a clubbing right hand dropped de Jesús to his knees. He beat the count but took more punishment over the next few rounds, and at the end of the tenth, he told Benitez that he could go no further. Unmoved, Benitez pushed de Jesús out of the corner for one last stand, which lasted less than thirty seconds. Sensing the kill, Durán moved in on a wobbly de Jesús with both hands churning. A looping right sent an exhausted de Jesús crashing to the canvas, where he took the full count on his knees.

Although de Jesús had absorbed a beating from Durán (as well as one from Antonio Cervantes in losing a decision for the WBA super-lightweight title in May 1975), he rebounded by outpointing Guts Ishimatsu for the WBC lightweight title in Bayamon in May 1976. In winning the WBC championship, de Jesús became part of a unique geographic renaissance. From 1975 to 1978, Puerto Rico, an island with the population of Wales at the time, produced a slew of world champions, including Angel Espada, Sammy Serrano, Wilfred Benitez, Alfredo Escalera, and Wilfredo Gomez. Before Gomez skyrocketed to the kind of fame that bordered on religious mania in the late 1970s, it was de Jesús who captured the imagination of Puerto Rico. During that era, Wilfred Benitez was recognized for his eccentricity as much as he was for his precocious ability, and Alfredo Escalera, although popular, was admired chiefly for a crowd-pleasing style emphasized by his habit of carrying a snake into the ring with him. De Jesús, on the other hand, exuded class. His neat counterpunching style, mixed with nimble footwork and an accurate jab, was the blueprint from which Gomez and future champions such as Edwin Rosario and Victor Callejas plotted their own nifty moves.

De Jesús defended his WBC title three times in Bayamon, turning back Hector Julio Medina, Buzzsaw Yamabe, and Vincent Mijares—all by stoppage. Finally, nearly four years after their last meeting, the scene was set for de Jesús and Durán to renew their hostilities, this time for the undisputed lightweight championship. A few months after beating de Jesús in Panama City, Durán spoke to the Miami Herald about his toughest foe: “I would not like to step into the ring again with Esteban,” Durán said, “but if it comes to it, I will knock him out again.” According to promoter Don King, staging the rubber match was just short of hard labor. “It was a job just to get the two managers of the fighters to even think about a match,” King told Sports Illustrated. “They had fought twice and neither wanted to fight a third time. First I convinced de Jesús. But the hard part was convincing Eleta. Then, when we did agree, trying to find a site that pleased him was almost impossible. One place was too cold; the next too hot. A third place, somewhere in Africa, was OK, but then Eleta didn't think he could get Durán's money out. He finally said yes to Las Vegas.”

Except for a few heated insults exchanged before their previous fights, Durán and de Jesús were fierce but not enraged competitors. In the days before their unification match, however, Durán made his feelings about de Jesús clear. “I don't like him for a lot of reasons,” Durán said, “mostly because he is the only man ever to beat me. And he is the only man to ever knock me down. I don't like him for a lot of reasons, but I have to respect him for them.” Their rivalry reached critical mass at the weigh-in when both camps took part in a scuffle that made the usually unflappable Don King jittery about the possibility of having to postpone the fight.

On January 21, 1978, Durán and de Jesús met at Caesars Palace in a bout broadcast nationally by CBS. Already hollowed out by a drug habit that predated his championship reign, de Jesús looked slack during the prefight instructions. He entered the ring a 5-7 underdog that afternoon, but the truth was that de Jesús, at twenty-six, was only the latest nostalgia act to hit the Vegas strip.

To make matters worse for de Jesús, he was now facing a Durán at his absolute peak. Durán, a juggernaut when he flattened de Jesús two years earlier, answered the opening bell by jabbing and circling. By adding guile to his attack, Durán ensured that de Jesús never had a chance at victory. Although he boxed well in spots, de Jesús was forced into the uncomfortable role of aggressor for most of the fight. In the twelfth round, he closed in on Durán, who connected with a trip-wire right hand—half cross, half uppercut—that dropped de Jesús in a heap. Showing remarkable courage, de Jesús crawled across the ring and hauled himself upright with the aid of the ropes. When the action resumed, Durán battered his bruised adversary with both hands until the fight was finally halted.

A year after unifying the lightweight title, Durán would abandon his title to focus on the welterweight division, where in less than two years he would notch his greatest achievement: a stirring win over Sugar Ray Leonard in the first superfight of the 1980s.

For de Jesús, losing to Durán in their rubber match accelerated his downward spiral. Manny Siaca, who trained de Jesús in the last stages of his career, told the New York Times that de Jesús no longer believed his career could be salvaged. “He felt depressed, that it was the end for him, that he didn't have it anymore.”

In his last fight, de Jesús challenged Saoul Mamby for the WBC super-lightweight title in Bloomington, Minnesota, far away from the bright lights of Las Vegas and New York City, and as chief support to the main event featuring Larry Holmes–Scott LeDoux. On July 7, 1980, Mamby stopped de Jesús in the thirteenth round.

In retirement, de Jesús began making headlines for all the wrong reasons. Long considered a tropical Arcadia after years of travel brochures, celebrity cruises, and sun-washed tourism commercials, Puerto Rico has always had a dark heart at its center. As a hub between South America and the United States, Puerto Rico has been a drug-running stopover for trafficking, with the inevitable tragic consequences. Even now, on the verge of being a failed state, Puerto Rico is suffering from a heroin scourge that has left thousands of lives in tatters. Now adrift among the junkie subculture in Puerto Rico, de Jesús saw his drug habit grow worse. He was arrested during a raid in San Juan and charged with possession of heroin. Then, on November 27, 1980, fueled by a potent combination of heroin and cocaine, de Jesús turned a road-rage incident into a tragedy when he shot and killed an eighteen-year-old after a high-speed chase on an expressway. He was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. At Rio Piedras State Penitentiary, de Jesús became a preacher, and daily prayer meetings became part of his routine. In 1985, when de Jesús found out that his brother (with whom he shared needles to inject heroin) had died of AIDS, he had himself tested by prison officials. The result was a death sentence: de Jesús tested positive for HIV.

Within a few years, de Jesús was so ill that his sentence was commuted on the condition that he remain in an AIDS clinic for treatment. “The doctors tell me that I have anywhere from one to four years to live,” de Jesús said in a television interview in February 1989, “but I hope God will support me longer.” There would be no reprieve for the magnificent lightweight whose troubles—combined with his losses to Durán —would permanently overshadow his career. Three months later, he was dead.

A few weeks before he died, however, an ailing de Jesús received a visit from Roberto Durán, whose empathy brought him to Puerto Rico from hundreds of miles away. Durán met his ex–rival for the fourth and final time in a weathered milk factory converted into a makeshift sickbay.

During the late-1980s the growing AIDS epidemic sparked a national panic. Before that, however, before the number of AIDS deaths spiked from hundreds in 1982 to more than fourteen thousand in 1989, AIDS was virtually a taboo subject. It took the death of Rock Hudson, ex-Hollywood leading man, to bring sharper national focus to the AIDS crisis. Best known for his roles in Douglas Sirk melodramas and Doris Day comedies in the 1950s and ’60s, Hudson was the first recognizable face of a mystifying disease too often thought of as the bane of the underclass. Hudson, rich, famous, and preserved forever on celluloid as a handsome young man, died in 1985. By the late 1980s ACT UP, playwright Larry Kramer, Elizabeth Taylor, and the Aids Memorial Quilt (unfurled in front of the White House in 1988) raised awareness of an illness that had a near-apocalyptic air about it. Even then, however, AIDS victims suffered discrimination and the process by which the disease spread was still shrouded in ignorance. Under any circumstances, it seemed, AIDS was something to fear with almost pathological intensity. But Durán immediately moved in to embrace de Jesús. “When I see him there so thin,” Durán told Christian Giudice, “my tears run out because he used to be . . . a muscular guy. I start crying and I hug him, and I kiss him and I tell my daughter to kiss him.”

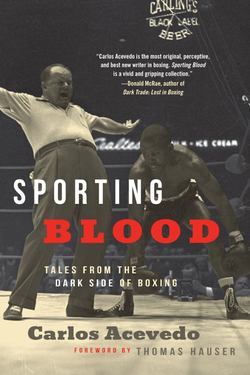

This act of compassion was captured in a photograph that was distributed worldwide by the Associated Press. In stark black and white, it reveals two warring selves, now achieving another kind of glory, an acknowledgment of human frailty and the bonds between us all, a haunting memento mori.