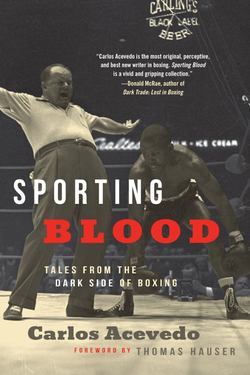

Читать книгу Sporting Blood - Carlos Acevedo - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Right on for the Darkness ON AARON PRYOR, 1955–2016

Оглавление“One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche

◆ ◆ ◆

From the beginning, Aaron Pryor, who died on October 9, 2016, was at odds with the world. Or, perhaps, the world was at odds with him. One of the most exciting fighters during an era when action was a prerequisite for fame, Pryor matched his unbridled style in the ring with an apocalyptic personal life that kept him in boldface for over a decade.

Pryor was an at-risk youth before the term came into vogue. Dysfunction was in his DNA. He was born—out of wedlock—in 1955 in Cincinnati to an alcoholic mother whose moodiness could lead to impromptu gunplay. Sarah Pryor, née Shellery, who gave birth to seven children by five different fathers, occasionally whipped out the nickel-plated hardware when some of her brood became unruly. Years later, she wound up shooting her husband five times in the kind of supercharged domestic dispute in which the Pryor clan excelled.

◆ ◆ ◆

Pryor had a family tree whose branches were gnarled by tragedy and whose roots were blood-soaked. One of his brothers, Lorenzo, was a career criminal who escaped from Cincinnati County Jail and eventually wound up doing hard time for an armed robbery conviction in Ohio. Another brother, David, became a transsexual hooker, while his half-brother was shot and paralyzed by his father. His sister, Catherine, stabbed her lover to death. As if to solidify the epigenetics involved in the Pryor family—and to concretize the symbolism of the phrase “vicious cycle”—Sarah Pryor had seen her own mother shot and murdered by a boyfriend when Sarah was a child.

◆ ◆ ◆

As an eight-year-old already at sea in chaotic surroundings, Pryor was molested by a minister. Shame was never far beneath the surface of a man who would eventually earn millions of dollars and worldwide fame as one of the most exciting fighters of his era. On the streets of Mount Auburn and Avalon—where race riots in 1967 and 1968 left bloodstains caked on the sidewalks—Pryor was left to his own devices in a time and place where social services barely existed. As a young boy, he was virtually homeless for years, couch surfing when he could, sleeping in doorways or under awnings whenever his mother locked him out of the house. He was an Over-the-Rhine dead-end kid before finding refuge in a boxing gym as a teenager.

◆ ◆ ◆

After losing a decision to Howard Davis Jr., in an Olympic trials box-off in 1976, Pryor returned to Cincinnati at loose ends. That same year, he made his debut, as a late substitute, and earned a payday of $400 against an ex-kickboxer. By contrast, Davis Jr., had a contract from CBS in hand worth nearly $300,000 before he had ever stepped into a pro ring. The TV gold rush had begun, and Pryor had no chance to stake a claim. Soon Pryor became the hired help—as a sparring partner—for the stars who had left him behind: Davis and Sugar Ray Leonard.

◆ ◆ ◆

Not long after signing Pryor to an exclusive deal, Madison Square Garden—in those days one of the top promotional firms on the East Coast—called a press conference to announce that “The Hawk,” then a lightweight, could not get a meaningful fight. So in 1980 Pryor turned to the Robin Hood of prizefighting, Harold Smith, for help. Smith, with money embezzled from Wells Fargo, managed to lure WBA super-welterweight champion Antonio Cervantes to Cincinnati, where Pryor rebounded from an early knockdown to overwhelm and eventually stop the defending champion, who had as many successful title defenses under his belt as Pryor had fights.

◆ ◆ ◆

Like Leon Spinks, the ditzy man-child sent careening through short-lived fame, Pryor often received press coverage that bordered on mockery. It was Spinks who became the target of talk-show hosts and a Richard Pryor skit, but Pryor was no less susceptible to lampooning than “Neon” Leon. His pre–hip-hop Kangols, Cazals, and Day-Glo tracksuits were ready-made for ridicule. Malapropisms popped out of his mouth like Mentos. The bad press he received, he said, was due to “misrepresentation of my personality.” Later, he removed the gold cap from one of his front teeth, began wearing suits in public, and even toted a briefcase from one press junket to another.

◆ ◆ ◆

What made Pryor appealing was a fierce ring style seemingly at one with a personal outlook that bordered on madness. Pryor scored five consecutive stoppages in defense of his junior welterweight title and in the process astonished viewers with his frenzied performances. For Pryor, being knocked down often meant popping right back up to charge at his opponent before the referee could issue the mandatory eight-count. Gaetan Hart, Lennox Blackmoore, Dujuan Johnson, Miguel Montilla, Akio Kameda—all were worn down by Pryor and his cyclone attack.

◆ ◆ ◆

As much chaos as Pryor surrounded himself with between fights—he made headlines in 1980 for being shot by his then-girlfriend Theresa Adams—in the ring, everything was a strange kind of zen. “Controversy is still going to come, because that is my style and some people still don't like me,” Pryor once told KO Magazine. “I don't care, they just want to see me get beat. I still got something to prove to those people. I still want them to say, ‘That nigger's crazy,’ about me.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Three world titles into his career, Alexis Arguello finally broke into the mainstream after stopping heartland teen idol Ray Mancini in a 1981 lightweight title defense. After scoring a brutal thirteenth-round TKO, Arguello captured the imagination of a national television audience by consoling Mancini with a tenderness antithetical to the general mores of a blood sport. You could not ask for a saintlier contrast to Aaron Pryor.

◆ ◆ ◆

November 12, 1982—The Orange Bowl, Miami, Florida: Aaron Pryor TKO 14 Alexis Arguello

Before the bell rang, Pryor shadowboxed, paced, flurried with intensity. As he was being announced, he pointed his gloved fist at Arguello and held his pose, glowering, for nearly a minute. “I intended to make Alexis believe that I was going to . . . kill him,” Pryor later recalled. Soon the men met at ring center and nearly twenty-four thousand spectators watched, spellbound, as Pryor and Arguello abandoned themselves to bloodlust.

◆ ◆ ◆

“After the fight was stopped, Arguello was stretched out on the floor with an oxygen mask held to his face. For the moment, he was not an athlete, not an admirable public figure, but the victim of an accident, as if he had been hit by a drunken driver, or a coal mine roof had fallen on him.”

—George Vecsey

◆ ◆ ◆

There would be no salvaging either man. For both Pryor and Arguello, the future would be an illusion. “After I beat Arguello is when I started to lose myself,” Pryor once recalled. “I didn't know quite who I was for a long time.”

◆ ◆ ◆

At last, Pryor had earned the respect and distinction he had craved his entire life. Or had he? Within hours, his greatest accomplishment was eclipsed by the actions of his trainer, Carlos “Panama” Lewis. Twice—after the first round and after the thirteenth—Panama Lewis instructed Pryor to drink from a mysterious black bottle—“The one I mixed.” “The Black Bottle” was not black at all, in fact, but a strange Robert Ryman off-white. Grainy video reveals that it seemed to be wrapped in athletic tape as if to hide its contents.

Panama Lewis would go on to serve a prison sentence for removing the padding from the gloves of Luis Resto in a 1983 fight against Billy Collins Jr. “I had seen Panama Lewis getting to do this with Aaron one time,” recalls Frankie Sims, former co-trainer of Pryor. “He was getting ready to cut the inside of the gloves and take the pads out. I looked right at him and shook my head. ‘Don't do that man.’ He knew I was dead serious, and so he didn't cut out the pads, but he was very crooked in my opinion. He didn't help Aaron's reputation at all.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Pryor essentially trained himself for the rematch with Arguello in 1983. Sparring numberless rounds sans headgear, Pryor was hospitalized for a thunderous migraine. Under-conditioned, surrounded by chaos, and already battling a drug addiction that would leave him on the brink of death more than once, Pryor battered Arguello in Las Vegas, scoring a tenth-round TKO and leaving the limelight for a life on the margins.

◆ ◆ ◆

After being introduced to crack by his wife, Pryor spent the next ten years in a perpetual haze. A Sports Illustrated profile in 1985 revealed Pryor, death-in-life, gray and skeletal, his surroundings as dreary as those of a drifter wandering the streets from day to dire day. For Pryor, nothing mattered now except the rush. He placed his life and his career on a funeral pyre. “Miami is the drug capital of the U.S. There are drugs at every other door. Living in that environment, I reached out for some help,” Pryor recalled. “My wife had divorced me. I was so hurt by rumors of the black bottle that I had no energy. I reached out and certain people did not give me their right hand. They gave me drugs.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Pryor rallied in 1984, against limited Nicky Furlano in Toronto, where he labored to a fifteen-round decision and revealed in the process a fighter—a man—who was beginning to fray. A year later, in 1985, Pryor struggled to a narrow points win over Gary Hinton in Atlantic City and disappeared, undefeated, into a permanent midnight.

◆ ◆ ◆

“I ain't The Hawk now. The Hawk is dead. I'm a ghost.”

—Aaron Pryor, 1985

◆ ◆ ◆

The mid-1980s, neon and glitz for some, were some of the bleakest years for Pryor. He was divorced for a second time. In October 1986, he was arrested for assaulting his mother. In 1987 he was shot in the wrist and held hostage by a pair of baseheads and his mother tried to have him committed. In 1989, he was arrested for possession of drug paraphernalia. There were more lawsuits and canceled fights than can be remembered. He went through trainers, managers, and promoters the way a hanging judge went through outlaws in the West.

Finally, after the lost years passed him in a blur, Pryor was sentenced to six months in prison for drug possession. For more than one court appearance, Pryor, who appeared indefatigable in the ring, overslept and arrived late. Recalled Pryor: “I immediately became a night person. There's no such thing as a crackhead being a ‘day person.’ The crackhead is up all night and sleeps all day. I also became very undependable. Whenever anyone asks a crackhead to do something, they'd better not hold their breath waiting for it to happen. The person using the crack only thinks of themselves, how something will benefit them, and the next time they are going to get high. They're not thinking about picking up the kids from school, meeting the in-laws for dinner, or having a family get-together on Sunday. It's all about getting high.”

◆ ◆ ◆

This was not the kind of habit that led to a few weeks in the Betty Ford clinic or could be overcome by an intervention. It was Do the Right Thing, J Is for Junkie, Night of the Living Baseheads deterioration. For loose change, a shambolic Pryor shadowboxed on street corners. Occasionally, he even sparred against neighborhood toughs in alleys and backyards. He shuffled from one crack house to another, took beatings from conscienceless thugs, suffered sexual degradation, and slept on curbsides under harsh lamppost light. Every urban wasteland was a mirror image of another during that era. Crack vials shattered beneath feet, abandoned buildings were repurposed for shooting galleries and smoking dens, crosswalks were ruled by vicious sentinels wearing Timberlands and waving Glocks. All blue hours were splintered by the pop-pop-pop of gunshots, the nonstop wail of sirens, and the falling, booming bass beat of Jeeps cruising the risky streets. Then the sun would rise again on chalk outlines, spent shells, sidewalks caked in flaking blood. But you would never think to find someone as accomplished as Aaron Pryor in that netherworld.

◆ ◆ ◆

“One time, a dope dealer thought I was so high that he could manipulate me into believing that I owed him $5,000. I argued with him and he pulled a gun on me and started firing at me point blank. I pulled out my own gun and started firing back. In a flash, there were two other guys by his side firing automatic weapons at me. It was a good old Wild West show. The bullets were whizzing by me and putting holes in my car. We must have been only twenty feet from each other. When I emptied my gun, I got in the car and drove off. That was the kind of madness I was living in.”

—Aaron Pryor

◆ ◆ ◆

In 1987, more than two years after his last fight, Pryor faced hard-hitting ex-prospect Bobby Joe Young at the Sunrise Musical Theater in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. It was too much for a disintegrating Pryor. Years of squalor had left him with a gray pallor. His vision, suspect for years, may have deteriorated to the point where he should not have been allowed in the ring. Before the fight began, Pryor had his mouth bloodied in a scuffle with Young's trainer, Tommy Parks. Young scored a knockdown in the first round, staggered Pryor repeatedly, and dropped the ex-champion hard in the seventh with an overhand right. As the referee tolled the mandatory eight-count, a wobbly Pryor dropped to one knee and made the sign of the cross. The referee reached ten.

◆ ◆ ◆

His umpteenth comeback, in 1990, was a travesty. A fly-by-night promoter named Diana Lewis decided that Pryor would be enough of a sideshow attraction to make the harsh phrase “blood money” a remunerative reality. Nearly blind in one eye, Pryor was granted a license to fight in Wisconsin, whose Department of Licensing and Regulation ruled that denying the tattered Hawk the right to fight was tantamount to discrimination. Pryor stopped Daryl Jones, his pal of many years, in three farcical rounds and returned to the streets.

◆ ◆ ◆

“I got so depressed, I contemplated suicide. Plenty of times. Not because the money was gone or even that I had wrecked my life. I wanted to die because I couldn't find a way to live. I didn't know how to start a new life.”

—Aaron Pryor

◆ ◆ ◆

“All of it had to do with drugs. With crack. He has been assaulted—mentally, physically, sexually. He's been beaten, not just with fists, but with guns, sticks, bats. Some of these leeches have taunted him to shadowbox for them. They have mocked him, humiliated him, threatened him. All for what? A little rock of cocaine? For that trash, they've made him beg. Made him do unimaginable . . .”

—Cincinnati trainer Mike Brown, 1993

◆ ◆ ◆

Lying in a crack house, seemingly on the verge of death, Pryor had an epiphany. He was rushed to a hospital with bleeding ulcers and underwent surgery. When he was released after two weeks—now sporting a long scar across his stomach, the last of several life marks—he headed straight for a church and to a new beginning, one that lasted for more than twenty years. Pryor became a deacon and a motivational speaker. He trained amateur fighters in Cincinnati. Aside from a few national television appearances alongside his son, Aaron Pryor Jr., a journeyman super-middleweight, “The Hawk” no longer had the spotlight on him. This new anonymity was a sign of serenity—something Pryor had earned with blood and sweat. The same way he had earned his Hall of Fame status in the ring.

◆ ◆ ◆

“I've had a phenomical . . . just a phenomical life.”

—Aaron Pryor