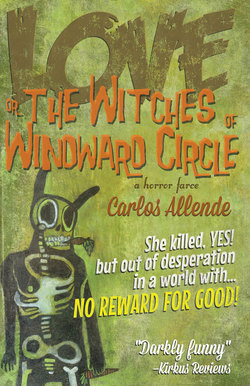

Читать книгу Love, or the Witches of Windward Circle - Carlos Allende - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

In which we meet the mother

and her three daughters

Once upon a time, there was an evil witch that lived in a small town by the sea.

She was a very perverted woman, this witch. Wicked, at her best behavior. She took pleasure in causing distress to her neighbors, killing their pigs and poultry, stabbing onions with a rusty knife, or ruining their crops and shindigs with hail and heavy rain, which she caused by peeing inside a hole dug in the sand and throwing more sand inside. She was a mean and hateful enchantress, with no sympathy for the dim or the silly.

She attended the Sabbath every Wednesday and Friday at the midnight hour sharp, where she reveled in the most vicious and depraved anti-Christian acts: blasphemy, sodomy, and infanticide. She was always the gayest and the most heavily bedecked at these balls, and when it came to presenting her master, the Prince of Darkness, with a list of her evil deeds, she was the first to approach his circle of sinful seducers, and the one who brought them the fattest children, too.

Twice a year, on the eve of May the first and on the eve of All Hallows Day, on October thirty-first, she renewed her vows of eternal fidelity to Satan with a sacrifice of her own flesh—a tooth, a pint of blood, or a finger nail. On Sundays, however, she wore a veil and attended Catholic mass. This is not uncommon among witches, to live a double public life, pointing the specks in the eyes of their neighbors, while carrying a log of hatred and shame inside. She received Communion, sang the Sanctus, and offered the sign of peace, just as Christian women commonly do, so well pretending to be afraid of the Church’s promises to prize the just and punish the vile with the agony of fire in the afterlife, with such an apparent conviction of her faith, that she fooled each and every one of the parishioners—all of them! From her husband, a rather ninny fellow and a drunk, to the priest, a quick-witted gentleman, well-traveled and not too old; from her sisters, rather femsy little dames, to her neighbors, rather proud; from her neighbors’ friends, rather stony, to her sisters’ husbands, rather boring, and—everybody! Except, of course, the One That Can See All, our Lord. Yet, He preferred to remain silent, neither deaf nor blind but consensual to free will and to the fact that it is human nature to sin and to be tempted.

Now, just as virtue brings along its own reward, evil brings its own penance. As time went by, the vileness in the witch’s soul and the constant sacrifices of blood took their toll on her constitution. She grew weaker and bitterer with the years, and eventually she fell ill. One morning, her bones felt so brittle that her legs didn’t have the strength to carry her out of bed, not even to go take a piss in the garden. A day later, she found she couldn’t raise her head from her pillow.

That day, Saturday, September 7, 1912, a sunny day perfumed by the honeysuckles, a day that called for sliced fruit and a lazy stroll by the water, the woman said to the youngest of her three daughters, with the conviction of a born-again Christian when questioned about the veracity of his faith: “I am dying.”

The born-again Christian would have said, “I believe,” instead of I am dying, and then condemned the way others conduct their own private business, but what we want to portray is not the ways of those who are ready for the rapture, but the similarity in the certitude of her tone to that of a man in possession of an unequivocal truth: “Me estoy muriendo,” the woman said in Spanish, her mother language, and that’s indeed what was happening. She was bound to leave this earth.

The young girl looked at her mother. Her little face furrowed with grief, but not a peep came out of her mouth. She feared that the sound of her voice would hurt her mother’s ears just like her mere presence hurt most people’s eyes. She was ugly. As ugly as her mother’s crimes: Too much hair and too much nose. A turnip for a chin. Toad-like eyes, teeth like a picket fence in the wake of a windstorm. A mouth as big as a purse. Her age? Unknown. Between twelve and fourteen. She looked ten. Raised with little love and many beatings, fed sporadically and poorly, she had grown rachitic and feeble.

“We have a nice house,” the woman said next, missing the desolation of the poor bedroom. Other than her bed and the chair her daughter was sitting on, a bare light bulb hung from the ceiling and an old armoire whose door refused to close was all the furniture the room consisted of. “Not as nice as the ones they’re building by the beach, perhaps, but much better than the old one, remember?”

The young girl nodded. For an instant she wondered whether the woman was speaking to her or to the invisible spirit of an unknown dead relative; her mother’s tone had never been so affable.

“After I die,” the mother continued, “this house will be for your sisters. You’ll stay if they let you stay; you’ll leave if they ask you to leave.”

The young girl nodded again.

“My two angels. In their white summer dresses. Call them. I want to see them.”

No more was needed. The young girl dashed out of the house through the kitchen and climbed the exterior staircase two steps at a time up to her elder sisters’ bedroom on the second floor.

The two of them were still in bed.

Eighteen-year-old Victoria dismissed her words as just rubbish. “Today is Saturday,” she complained, pulling the sheets over her head. She sounded like a morning bird.

Rosa nodded in agreement. “Nobody dies on a weekend.” She stretched her arMs. Her voice was the tinkling laughter of a brook.

She was sixteen.

“Tell her that we need to sleep.”

“Tell her we’re tired.”

The young girl’s heart shriveled with disappointment, but she dared to make no comment. Her sisters needed rest. Would it be too imposing to wait for them by the door? She slid her fingers over the chest of drawers and surveyed the room. Her sisters had such nice things! Lace curtains, a Chinese lamp, and colorful cards and illustrations pinned to the walls. And they were beautiful, indeed; they were as pretty as a dollar sign, as pretty as to force a stranger passing by to compliment their looks with a whistle, as pretty as to drive a man insane if they were kind enough to regale him with a wink. Brown eyes, dark and silky hair; mouths shaped like little roses, with teeth as white as pearls and lips as red as ripe tomatoes; noses like a pinch of fresh dough, and hands so delicate as if made to pull the feathers off a hummingbird without disturbing its flight. Not one freckle.

Victoria farted.

The young girl closed the door and hastily returned to her mother’s bedroom.

Neither of her sisters cared to go downstairs until it was time for breakfast, an hour later. The young girl was serving them at the table when they heard the mother howl a second time: “I don’t want to die!”

Rosa spilled some of her coffee.

Victoria’s fork fell to the floor.

“If I die, I will be dragged to Hell and remain there forever!”

The young girl rushed to clean the spill with a cloth napkin and then provided Victoria with a clean fork.

“For God’s sake, Mamá!” Rosa hollered. “It’s only a cold. We’re having breakfast!”

But the mother wouldn’t stop. She kept wailing and crying until the two sisters left the table and entered her bedroom, ready to give the woman a couple of strikes on the temples for ruining breakfast. Upon seeing the gray in the woman’s face, the purple spots under her eyes, and feeling the stench of blood and vomit coming from a bucket by her side, they were convinced about the seriousness of the matter, however. The witch was dying.

“¡Mamá!” The two sisters cried at once, throwing themselves to the woman’s bed, and the one that received the blows was their younger sister, for not having alerted them sufficiently.

Without their mother, they reckoned, they’d be the same as orphans.

“We cannot count on Papá!”

For their father was a ne’er-do-well drunkard whom no one had seen in the past three days.

“We’ll be all alone!”

And neither had felt the need to go look for him at the dives the man frequented.

“What will become of us without our mother?”

“Who will look after us?”

Tears were shed, kisses, snot, and saliva were exchanged, until they reached a point when timid smiles followed sniffles of resignation.

Rosa and Victoria almost canceled their going out that day to stay home instead, and cry by the side of the soon to be departed. It was Saturday, though, and there was going to be a derby at the pier.

“And then lunch with the girls from the water-plunge!”

“And King Neptune is going to be crowned at sunset!”

“And then there is a ball at the auditorium!”

The same ball to which the judges of the Miss Venice Pageant, Summer of 1912, they had been told, had been invited.

Consequently, the two of them elected not to stay, even if it would break their hearts to miss their poor mother’s passing.

And who could blame them? September was a great time to be in Venice. Not the Venice in Italy, where the stench coming from the canals makes it impossible to live during the hottest weeks of the summer, but the Venice of America, where the sea breeze keeps the air pure and the weather mild for the entire year; the Coney Island of the Pacific, full not of crumbling palazzos and dusty churches, but of elegant hotels, expensive souvenir shops, and casinos, built not of marble and stone, but of brick, wood, and plaster; the Venice with a twelve-hundred-foot long amusement pier, complete with an auditorium, a Ferris wheel, a ship-restaurant, and a dance hall; the Venice with a swimming lagoon and two roller-coasters; the Venice that attracted tourists by the tens of thousands every weekend; the Venice of scantily dressed women holding umbrellas promoting real estate by the beach; the Venice where oceanfront mansions, multiple-story apartment buildings, and rows and rows of miniature, tent-like houses along the man-made canals were being built every day, each one more exquisitely crafted than the other.

Their own house was one of these little cottages facing the Linnie Canal. It wasn’t much, but it had a nice front, an entry hall big enough for a coat rack and an empty bookshelf; a living room with a sofa and a small dining table; a kitchen with a six-burner stove that ran on coal so they never had to worry about burning their bangs in the fireplace, and a washbasin. There were only two bedrooms: one downstairs, for the mother and her mostly-absent husband, and one upstairs, with its own private entrance, for the two eldest daughters. The youngest slept in a toolshed in the backyard.

“Don’t let me die alone,” the mother begged again.

“We won’t,” Victoria responded.

“Our little sister will stay behind to take care of you,” said Rosa.

They said their goodbyes and Rosa and Victoria went back to their bedroom, dragging along the young girl to do their grooming.

“I wish she’d stop,” lamented Victoria, closing the window so they wouldn’t hear their mother’s wailing.

“We know she’s dying, all right,” said Rosa, standing on a low stool while her little sister mended the hemline of her dress. “We don’t need to be reminded every second.”

“We’re not insensitive beasts.”

“If she makes me cry again,” Rosa bent down, so she could see herself at the vanity table, “I’ll have puffy eyes and I will look horrible at the derby. And I don’t want to give O’Leary that pleasure—you were supposed to be taking care of her,” she rapped the young girl’s head with a knuckle. “It is your fault she’ll die.”

The young girl hunched her head down and continued sewing. She felt a lump form inside her throat, but did her best not to cry. When she cried, the beating was harder.

Rosa and Victoria left the house shortly afterwards, transformed into two red-lipped baboons, not by the miracle of magic, but by the tragedy of makeup too liberally applied. The young girl returned to her mother’s side and remained there for the rest of the day, wordless, but not less loving, combing the moribund woman’s hair with her hand and wetting the woman’s pillow with her tears.

The two mean sisters returned from the ball a little before midnight. What an adventure! The best day of their lives! They had drunk and danced and teased and left so many unfortunate young men brokenhearted. O’Leary had seen the holes in the soles of their boots and made some unpleasant comments. Her lackey, that imbecilic Triggs, had called them greasers. They were jealous. In their hearts the two sisters knew they had been a success. They were the two most beautiful girls in Venice. Any time soon, each would catch a good husband. And what a pair of wonderful husbands they’d be!

“Rich!”

“Handsome!”

“A prince from a foreign land and his cousin!”

They were all titters and giggles as they climbed the stairs one step at a time, holding themselves from the railing, commenting on the promises of eternal love they had pulled from a married man, when their younger sister summoned them again into their mother’s bedroom.

“Please,” the mother begged with a raspy voice, “go call a priest. I want to die in contrition.”

A priest? For a witch? More tears, laments, and runny noses! And the promise that, even if it would be the last thing they did in their lives, they would get a priest to their mother.

But the two of them had drunk copiously. They fell twice, once trying to get out of the house and then when they stepped into the rowboat—through the canals, Victoria had insisted, it would be much faster.

Rosa ended up falling into the water.

“My dress!”

No time to lose! Her mother wanted to die in contrition. The young girl helped her sisters back into the house, then jumped onto the boat and rowed herself towards the Grand Canal, guided by the lights and the music coming from the Race Thru the Clouds roller coaster; under several bridges, by the Bath House and through the big lagoon, all the way to the Venus Canal in the limit with Ocean Park—it would have been faster to run, she realized, puffing, but she didn’t stop rowing. She reached Second Avenue, then ran to the house of the only Catholic clergyman she knew, on Fourth Street. The fireworks coming from the pier illuminated her way. She rapped on the door insistently, until the priest’s maid answered. Between sobs, the young girl explained to the woman her desperate situation. She waited a good fifteen minutes for the maid to come back, accompanied by the priest, still getting dressed and reprimanding the woman for letting the child wait in the cold. The man checked the contents of his valise, put a couple of consecrated hosts inside, and followed the girl back to the boat.