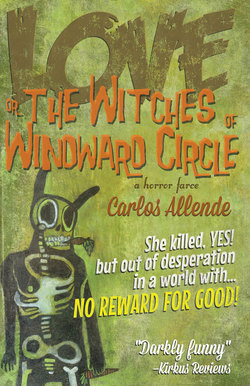

Читать книгу Love, or the Witches of Windward Circle - Carlos Allende - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

In which we are told how the third daughter was conceived

The witch explained:

“I had a niece whom I once cured of scabies by rubbing the fat from a skunk on the red spots in her privates while she recited the Lord’s Prayer backwards. Because of this, she came to suspect that I practiced witchcraft. However, she couldn’t tell that to her parents for fear of revealing how she had gotten sick in the first place. Thus, she only shared her suspicions with the boy that had given her the disease originally. This was a putty-faced fifteen-year-old lad with long limbs that made him resemble a walking windmill, a pointy chin, the fever of a dog and, apparently, the brains of one, for he decided to visit my home not to get rid of his itch, but to request a magical misdeed.

“What the boy wanted was a hand of glory, a lamp made from the amputated hand of a man hanged for stealing, whose purpose is not to disperse the shadows in a room when lit, but to immobilize people, and unlock any door the porter came across. What couldn’t he do with such a thing? Spy on young ladies when they took a bath? Steal the wallets from their husbands?

“The boy had learned of the five-finger candelabrum from a carny, and thought that if I were, indeed, a witch, I would be able make such a lamp for him if he provided the material.

“Coincidentally, a close relative of the boy had just died in a neighboring town, suspended by a rope for thieving cattle. Considering that a dead person needs not two hands to rest in peace, especially if one can be reused as a master key, he chopped one of the mitts from the body. ‘¡Perdón, papá!’ he said, and consoling himself with the thought that heaven would provide the deceased with a pair of white wings in the afterlife, he trudged the long way to the beach with the bleeding hand wrapped in a pall.

“He arrived at my house by nightfall. A thick layer of fog had settled onto the marsh. He knocked on the door three times. No one answered. He spied through the windows, but couldn’t see anything inside. He walked around the house and found the black goat that served me as my familiar sleeping on a pile of hay. The fiend had promised to stay home all night and watch my two girls and my drunken husband, sleeping it off inside, while I attended the Devil’s Ball.

“The boy decided to sit down and wait. To pass the time, he started throwing rocks at the goat. The beast wouldn’t move. It looked so tamed, the boy thought of mounting it as if it was a horse, just because, to have some fun. He grabbed the buck by the horns and passed a leg over its back. All of a sudden, he found himself traveling through the air, faster than a bullet, high above the clouds, high and high above, until he and the goat landed thousands of miles away on top of a hill where the Master of all Badness presided over an infernal ball, seated on a wooden stool thirteen feet in height.

“That night was Halloween, and hundreds and hundreds of bare-breasted women danced around the Devil, singing hurrays to his evilness, spitting on the Christian cross and celebrating mayhem and mischief as others celebrate friendship and love in May, while double the number of spirits flapped their wings above them.

“Such a vision would have scared the bravest soldier on this Earth, but to the boy, an orphan used to sleeping in stables, with no better place to go than jail, the smell of roasted pork—a child being broiled alive on a stick, he’d reckon later—the abundance of wine and liquor, the beating of the drums, the crying, the howling, the stomps, and the vision of half-naked women running around the throne, some on all fours, pointing their bottoms up, some walking backwards, like a crab, arching their backs to the ground, sweeping the grounds with their hair and thrusting their hips upwards, the vision of all this, convinced the boy that the place he landed in couldn’t be such a bad place after all, and he joined the unclothed merriment in good spirits.

“He had been drinking and dancing for a while when he saw me, at that moment surveying the ground for dandelions, my head bent down and my rear end pointing upwards. Feeling aroused, the boy approached me from behind. Thinking, on my part, that it was a demon-friend who so unexpectedly claimed my body, for it is not uncommon that, during the feast of Sabbath, when the abundance of fumes and liquor has driven women to the edge of sanity, witches engage in the sport of fornication with all sorts of aerials, as well as with other witches, male and female, and even with animals or elongated objects, like pokes or door knobs—thinking it couldn’t be but a fiend, the one that courted me so unforeseenly, one with the noblest of intentions, for as mean as Satan worshippers are, they’re never so inconsiderate as to make a witch a mother without her knowledge and permission, I rushed to pull my knickers off and salivate my parts. I closed my eyes, tightened my fists and bent to my lowest.

“As said, whenever my husband wanted to have intercourse with me, I presented to him the wrong conduit, so as to not become pregnant. This time, however, thinking it was a fiend who poked me, I offered the attacker what a poet would have called my rose—I feared the cold, scaly member demons have, and how painful it can feel inside the anus. Yet, the thing that the boy stuck inside of me felt rather warm, and it hurt much less than a demon’s instrument. I became concerned… ‘Why, I didn’t know a woman’s smell could be stronger than a dog’s!’ the boy exclaimed aloud. Hearing this, I confirmed my suspicion: the one inside me was a mortal man.

“I tried to pull off, Father, but the chap held me even tighter. He told me not to worry, that he would do as Judah’s son, Onan, and pull out at the last minute. I resisted at first, I said I didn’t want to, but the rhythm was not unpleasant; rather appealing. And the music was wild. And the air was inviting. And I had drunk so much, I had smoked so much, I had danced so much, and I had suffered so much for so many years at the hands of a man that didn’t love me, a man that battered me at the least provocation, a man that smashed my face against the wall should I dare to speak before I was spoken to, that I simply let go…

“I became expectant. That would have been it for the boy, but about a month later, before I realized I was with child, he got invited a second time to the Sabbath, so popular the ardor of a fifteen-year-old lad can be among certain women. He mounted the goat again and flew across the space, high and high above, to land on top of the hill of sin and idolatry in the middle of a party to mischief, and clumsily as he could walk with his trousers to his knees, he chased witch after witch, hag after hag, promising to please them all with his teenage vitality.

“He made a trip like that once more, on the eleventh night after Christmas, and after that he stopped. He had a rather fertile disposition and not one, but four of us had become pregnant, and so much in trouble were we now, one being the niece of a bishop, the second the servant of a devoted clergymen, the third the sister of a Cardinal, and the fourth, your humble servant, Father, an active member of my parish who wanted no more cheeky, impertinent gamines to make my life more difficult—so heavily in disgrace were we, that we decided to punish the felon cursing his parts with a disease so bad that he would feel no desire to be with a woman ever again. His manhood started to squirt a putrid squim when he peed, and began getting smaller and smaller, until one day, six weeks afterwards, it disappeared. As much as the boy looked for it within his bush, he could find no trace of it.

“He decided to visit my house a second time and ask for a cure for his lost virility. He knocked on the door three times. I peered through the window. It was the time of the day when the shadows grow longer and the cicadas start chiming. Seeing my enemy outside, I thought first of not opening the door, but I had just finished with my chores for the day and I had nothing else to do before supper. I lifted the latch and asked the boy what he wanted.

“The boy wasn’t angry. He presented himself in a very gentle manner, identifying himself as one of my previous lovers, assuming that after him there would have been many more, perhaps, and that I might have some difficulties in keeping track of the number, and as the son of so-and-so, related to the Talamantes, from nearby.

“‘What do you want?’ I growled, impatiently. I cared not for his relationships and now that my belly had grown to the size of a watermelon, I had little patience for this sort of impertinences.

“The boy admitted his guilt and kindly expressed his remorse for getting me pregnant, but that he deserved not to be punished so severely, when he had pleased me and many more so greatly.

“I replied that I didn’t know what he meant.

“‘I lost my dick,’ the boy said.

“‘Did you?’ I asked, trying to suppress a smile of derision.

“‘And I’d like to have it back,’ the boy insisted.

“‘Well,’ I said brusquely, ‘now that I am so fat, I cannot clip my own toenails.’ And, indeed, Father, I looked as big then as if I was about to explode with triplets.

“The boy responded with an offer to do it himself.

“I shouldn’t have accepted, Father, I know that now; but I did. I went back inside the house to fetch a nail clipper. When I came back, I gave him the clipper and sat on the doorstep. The boy took my shoes off, then my stockings, then he clipped off my toenails; first the left foot and then the right foot, and when he finished, he started massaging my knuckles.

“‘That feels good,’ I remember I said, closing my eyes and letting my head fall to one side in a blissful gesture.

“‘Let me do something that will feel much better,’ said the boy, who, despite the corns and callouses on my feet, but much in accordance to a male his age, had become aroused, and started licking my toes.

“I let him do so for a moment. But then I feared that letting him kiss my feet would lead to some other business. I took the clipper back, put my shoes on, and commanded the boy to leave. I pointed to the faces of my girls inside, spying through the window.

“‘I’m still cross at you,’ I said. ‘Because of what you did to me.’ I pointed to my belly. ‘Now I can’t walk straight without waddling like a boat amidst the sea.’

“I hated that baby just as much as I hated my husband, Father. I couldn’t wait for it to be born and get rid of it. And now this boy was kissing my feet and wanted to lay with me in front of my two daughters and insult my honor?

“The boy got upset and responded that I should be grateful, if anything, for I would be a mother for the third time and that no one but him, a ‘handsome man of wits and not a half-cut clown,’ which was a clear reference to the miserable state of my husband, was to thank. He also said that babies are a gift from God, whatever the circumstances in which they are conceived, and that I should have naught but words of affection for the one inside me.

“I attended mass regularly, for sure, Father, every Sunday, yet I still found the mention of God offensive. I got mad. But I had thought of something. I responded to the boy that an elegant reasoning like that deserved to be prized, and let him inside my house… You can see that we’re poor, Father. Neither my girls nor I have ever known any riches. Back then, when we still lived in the old house, we were even poorer. Poorer than a rat cornered by the cat of a pauperized widow. The interior of that house was as sad as you could imagine: a table and a couple of chairs by the fireplace, a bed with a cast-iron headboard, a cupboard against the wall, and in the middle of the room, a galvanized tub full of dirty water.

“‘Show me,’ I said to the boy.

“The boy pulled his pants down.

“‘Here it is,’ I said, searching under the hair in his crotch and pinching between my fingers a little bulb the size of a lentil.

“My two little girls approached to see what their mother had found in the young man’s body. I showed them and they laughed giddily.

“‘It’s been there all the time,’ I said, to the boy. ‘You never lost it. However, I am afraid there is no solution to its size.’

“‘There must be one!’ the boy cried, pulling up his pants.

“‘Is there one to mine?’ I asked, pointing to my swollen belly. ‘Is there one to my grief?’

“The boy grabbed me by the neck. ‘You whore!’ he cried. ‘Unless you give me back my health, you shall die at my hands!’

“I didn’t expect that, Father. I only wanted to see him suffer. I got scared and so did my two daughters. They jumped against the boy to help their mother. One punched the boy’s bottom repeatedly, while the other tried to bite his leg. He kicked them off with a swish, but lost his grasp of me. I hurtled across the room, trying to reach a poker.

“Now the boy held my daughters by their braids, one on each hand. He lifted them up from off the floor and asked: ‘Which one of your daughters should I kill first?’

“I must say this, now, Father, in the boy’s defense. He was just as frightened and upset by how far things had gone as my daughters and I were. He snorted like a beast cornered by a hunter. His face was red and his eyes filled up with tears. He had reason to be upset. A man’s tool is a man’s pride. The girth and the length of a man’s bone are the girth and the length of his honor. He had been complimented often on the bulbous, mushroom-shaped head of his cock and the upward curve of his shaft and he wanted it back. But back then I didn’t see that; what I saw was that he was shaking my two girls as if they were rag dolls. I got terribly scared. I didn’t think that things would turn violent. All I wanted to do was to see him suffer. To make him pay for everything I had suffered in the hands of my husband. I begged the boy to stop, but he wouldn’t.

“The Devil came to my rescue. I saw the goat spying through the window, and inside my head I heard the voice of the Little Master whispering instructions.

“He told me to pretend to be defeated and then to open the back door of the house and point to a fig tree full of fruit that I had planted the year of my marriage. I did as told and to my surprise, instead of fruit, from the branches of the tree now grew male organs.

“‘Climb up,’ I repeated to the boy the Devil’s instructions, ‘and choose the one that fits best.’

“The boy let go of the two girls, who scrambled to hide underneath the bed. He stepped outside and climbed the tree…there were so many different members hanging from that tree! You would have found it very interesting, Father. There was one of every length, shape, and color as there are men of different sizes, shapes, and colors on this Earth. It took the boy some effort to find which one would be the most appropriate replacement for the one he had lost.

“His first choice was one with a big mushroom head, like the one he used to have. Repeating what the Devil instructed, I said: ‘You must not take that one; it belongs to a parish priest.’

“The boy chose another one, thick and veiny, much more so than the one he had before. As he was climbing down with it, I said: ‘You mustn’t take that one either, for you will get his flaws, which were many.’

“Not wanting to be ill again, the boy let the member fall to the ground. He climbed up again and reached for a third one, rosy and slick, like a dog’s penis.

“He said: ‘I think I want this one.’

“‘That will be then,’ I replied, ‘but that is the tool of a dog,’ and it truly was, Father, you could tell that easily, ‘and so a dog you will be.’

“And as I finished pronouncing these words, the tree withered. All the leaves fell off and all the fruits shriveled up and disappeared, as if winter had returned in an instant. The branch where the boy had been standing snapped, he fell down, and, the moment his body touched the ground, the boy was transformed into a small brown pup.

“I grabbed the dog by his scruff and handed it to my daughters, who sprung out of their hiding as if they’d been offered gold. They laughed, sucking up their snot, same as any child when they see their tantrums rewarded, that much they liked their present. Yet, instead of petting the pup and blowing kisses on its snout, as most children would do, they started to pull its tail and ears, and to pinch it.

“‘What are you going to call it?’ I asked, laughing.

“‘Nothing,’ said Victoria.

“‘It’s just a dog,’ replied Rosa.

“‘Dogs shouldn’t have names. They’re only animals!’

“‘They do not feel, they do not speak, they don’t have a soul. They’re worth nothing!’

“You could tell that the little pup felt terrified in his new form. He wailed and trembled, afraid of my two daughters. Eventually, he found consolation in the fact that it was better to be a complete four-legged beast in the hands of three witches, than an incomplete man in the hands of ill fortune. Now he had a home. He had none before. Now he could bark at the cows, chase the cranes and the seagulls by the shore, he could run on the sand, and do all the fun stuff canines do. I dare to say he remained happy in his new condition.

“The fact that my seducer had become a beast didn’t make me less pregnant, however. Twelve weeks later, I gave birth to my third daughter. Being the offspring of two humans, this one had a human face, a human body and two complete feet with ten chubby little toes, just as human babies ordinarily do. Yet, being the offspring of a rather plain woman, as I am, and a rather ordinary boy, as her father was, full of bumpy whiteheads and freckles, she came out a rather unattractive baby. Just look at her, Father. She’s quite ugly…”

One more time, the priest turned his head towards the door, this time to check on the third daughter. The young girl hunched up, embarrassed at her own ugliness.

The old witch went on: “Everyone that saw her commented on how poorly suited for terrestrial life she was, and recommended to instill in her from a very early age the idea of joining a convent. Even her godfather, a vampire with no intention of teaching her the ways of virtue, agreed to this. Can you imagine, Father? The daughter of a witch making a vow of celibacy to Jesus? Had she been a boy, I would have drowned her. But I thought that I might as well offer her in matrimony to the Little Master when she came of age. Alas, he too rejected her.”

The priest exchanged another look with the young girl, this time full of compassion. She was, admittedly, quite unsightly. To the poor gifts of nature—the hair, the mouth, the bulbous nose—you had to add the embarrassing gifts of adolescence: her face was covered with pimples. The girl reminded him of a featherless baby crow fallen from its nest to the ground, left to be eaten by the insects.

“What is her name?” the good man asked.

“Dumb-fuck?” the witch responded, trying to suppress a laugh. “Stupid girl? You-little-piece-of-shit? She doesn’t have one name, but many. Whatever insult is in vogue, whatever mockery sounds fit, whatever noun seems degrading and mortifying enough, whatever makes her cry and wish she had never been born, that is her name for the day. She was christened inside a church and wearing the family’s baptismal robe of white embroidery, an heirloom from before the Mexican war that had been in my family for generations, and she was given a name, in honor of the saint of the day of her birth; yet, nobody ever used it. The sad appellatives came from the beginning. Outside our family, everyone refers to her as Antonia’s third daughter, or as Rosa and Victoria’s little sister, or plain and simply with a contemptuous ‘you!’… ‘You!’ is what the nuns used to call me when I was a girl, during catechism class on Saturday mornings. ‘You, naughty little girl,’ they said, before swatting the back of my head with a ruler, ‘why can’t you be more like your brothers and sisters?’”

A coughing fit forced the woman to make a pause. The priest took advantage of the interruption to steal another look at the three girls. Rosa and Victoria had fallen asleep on the floor next to the young girl, who had hunched up as small as she could behind the door. The comparison couldn’t be crueler. The two elder were two angels, two swans, two diamonds; as selfish and ill-mannered as they were, they could only be easily loved and forgiven. The young ugly girl could only be hated. Why, she was as ugly as a tadpole! She was a reptile! Who could be so brave as to say he loved such a miserable creature? Not even the most heroic man on this Earth.

The priest guessed, and guessed correctly, that not one I-love-you had ever been dedicated to the poor girl. She was repulsive.

Yet, someone had loved her once.

“Only the little brown pup seemed to care for her,” the mother said, “wagging his tail, barking friendlily whenever he saw her approaching. He used to do the same with my two other daughters, if they were willing to play, and he used a similar type of bark to demand food from me as he used to demand it from her, if he was hungry, but no one else could approach his plate without being growled at; no one else could hold him in her arms and rock him like a little baby without getting bitten.

“Was it because he knew she was his daughter? I cannot say. After his transformation his thoughts became the thoughts of a canine. Maybe his devotion was only instinctual. Maybe because he was the only one below her, he was the only one to whom this unfortunate dummy didn’t shrug and frown but offered instead a smile, an ugly smile of missing teeth and green snot running down her nostrils, but still a smile; maybe he found her pretty, without really being so. Maybe it was just because of that silly insistence of dogs to love anything that seems remotely human.”

The priest noticed that the face of the young girl had brightened up as the witch spoke about her father.

“Love needs no spoken words,” contends a sentimental. We agree. The dog loved the little girl; one can tell these things with dogs, can’t you? Love can be expressed with a wet nose and tail-wagging, without the need of words. And the young girl had always known he was her father. The mother never hid from her or from her sisters the facts of their origins. “Give this to your dad,” she would say, handing her a bone, and the little girl knew well that her mother referred not to the sot sleeping it off by the stove, but to the dog scratching fleas on the porch.

For the most part, the little girl was nice to him. You could have said she loved him back. Every now and then, she held him tight, especially if it was cold and she had been left outside by her sisters; so tight, the poor dog needed to fight his way out to breathe, but once the air returned to his lungs, he licked her face gaily.

Sometimes, she scratched his belly and blew a kiss on his snout, or she searched his coat for ticks, or let him chase her down the shore until they ended up rolling on the sand, laughing. Yet, at other sorrowful, unhappy times, the little girl tied a rusty wire around the dog’s neck for a leash, or she pinched him, or she poked him with a stick, or she pulled his ears badly, as if to tear them off his little body, just because, out of boredom, for nothing else but vileness and lack of compassion had been taught to her by her parents; more so when she was mad than when she was happy, because her sisters had been mean to her, because the drunkard that thought himself her father had dragged her out of the house by the hair, or because her mother had slapped her, or sent her to feed the pigs without breakfast, all of which happened pretty much every morning. The little girl dared not fight her sisters, who doubled her in size, and she wouldn’t talk back to her parents, who smacked her at the least provocation, offensive as her little person was, but she could well abuse the beast, and she did so often, even if the little brown pup had proven to be her only friend.

That is the way of the world. The one you love will hurt you most.

Still and all, no matter how much harm the little girl could do to the little dog, he curled up next to her at night and licked her tears and boogers off whenever she cried.

“Oh, yes,” the witch resumed her confession, “that little brown pup endured the unendurable, with no more complaint than a high yip where other pets growl and show their teeth, until one time when, resentful because her two sisters had gotten candy after Sunday mass and she, instead, had gotten a box in the back of her head, the stupid girl took a heavy stone and let it fall upon the little pup while he rested. Luckily he saw it coming and slipped out just before the stone could smash his skull, although he couldn’t move fast enough to pull away completely; the rock fell on one of his back legs, breaking the bone in two.

“My husband had grown fond of the dog and made a splint out of two pieces of wood to save his leg. He knew how to immobilize a limb because he had broken Victoria’s arm once and learned from watching the doctor work how to fix it. The bone didn’t heal properly, however, and the poor beast lost the ability to stretch his leg all the way down and step on it. He was never able to walk on all fours again. Even so, he didn’t seem to care for the little girl any less. He continued curling up close to her at night and licking her tears whenever she cried; he still chased her down the beach barking gaily as if nothing had happened, same as before. The only difference was that the little girl now had to run more slowly.

“After her harrowing attempt at murder, she occasionally yanked his ears or threw dirt in his water bowl, but she never tried to kill the little pup again. For one thing, because she truly cared for him—he was her only friend—but especially out of fear, because the one time she had tried and broke his leg, my husband grabbed her by her neck and shook her head so rashly, she thought he would break her body in two, and she knew well that no one, not even the loyal little brown pup, would know how to make a splint to fix her.”

“What happened to the dog?” the priest asked, realizing he had yet to meet the man turned into a sack of fleas.

“He died a couple years ago,” the witch responded. “A pack of coyotes killed him. He was old, and very small, and with only three good legs he couldn’t run too fast. He was easy prey for the wild canines. My two elder daughters laughed so hard when they learned how the poor dog had died that they slightly wet their undergarments. I laughed, too. It’s hard not to laugh when they do; their laughter is like lilting water. But I felt his passing. I too had become fond of him. He had a name. We called him Skinny.”