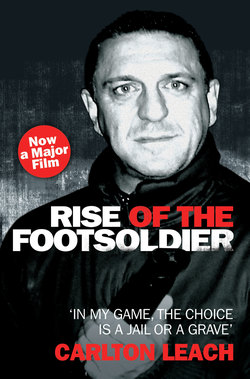

Читать книгу Rise of the Footsoldier - In My Game, The Choice is a Jail or a Grave - Carlton Leach - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Birth of a Footsoldier

I’m a great believer in fate and aura. I think what’s meant to be is what’s meant to be. I think about Tony and I think if I was meant to die that night in the Range Rover I would have done. We’re all born with a card and there’s a date on which we are going to die. There’s not much we can do about it.

I don’t know how my card is marked, but I know what colour it is: claret and blue. You could see West Ham’s grounds from the maternity hospital where I was born. I was born 1 March 1959, I’m a Pisces and I’ve always been a bit of a dreamer.

My childhood was full of music and parties. I grew up with the Beatles and I’ve got every single album. My mum preferred Elvis and so did all the aunts. I ended up being a bit of an Elvis impersonator as a kid. Then there was football, of course. I remember watching the World Cup in 1966 on a black and white telly. Vivid memories.

We weren’t badly off. The family went on holiday to Spain when I was eight or nine while other kids’ families were still going to holiday camps in the UK. But I was always aware that what I had in material things, I lacked in simple love. My mum, Audrey, was totally focused on her career. She ended up working on the administrative side of Barclays Bank and went as high as she could go in her department. She earned more money than my dad. I felt quite sorry for him sometimes.

Norman, my dad, had been in the Merchant Navy and he came out with quite a lot of money. That was important to him. He was a working-class boy from Dagenham and he’d lost his mother when he was 14. His dad, my grandfather, left the kids after she died and I always hated him for that. These days the kids would have been taken into care but Dad became a purser on the QEI and went around the world twice. He looked after stars like Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor and Robert Mitchum. He was prepared to work for a nice life.

Back home, during the Sixties, he and my mum opened up cafés. One is still going in Ilford, the Mocha – my dad gave it the name. Their customers included boxer Billy Walker and he and his brother and friends would come over after finishing their work as doormen at the Ilford Palais. They’d hang out and listen to the jukebox. When I was a baby I would be sat on Billy’s lap and he’d hold me up and say, ‘I’m going to teach him to look after himself.’

Then it all went pear-shaped for Dad’s business and he blew all his money. He laboured by day and studied at night until he qualified to be an electrician. We ended up moving from Ilford to a bungalow on Canvey Island and then finally settled in Forest Gate when I was two or three years old. Dad was a sparks until I was about nine or ten, when he decided to emigrate to Australia.

We had all the vaccinations, he sold all the furniture, booked places on a boat and the house sale was agreed. The purchasers, however, came back and tried to knock the price down by a massive amount. Dad refused and got another job in order to buy more furniture for the house to tide us over. In the end, the furthest we moved was East Ham, when I was about 13.

With both my parents doing overtime, we kids were quite often left with babysitters or sometimes with the people next door. I’d watch the other kids sitting on their parents’ laps, cuddling and kissing. I didn’t even see my parents when they came back home: they’d just cook dinner and I would be going to bed. Without that affection, I had to rely on myself and I started to develop a bit of inner steel. I just got on with life, but I never enjoyed having to stay away from home. Sometimes I’d say that Mum wanted us home earlier and I’d get into our place by sliding down the old coal chute that went into the cellar of the old Victorian house and let my sister, Tracy, in the front door. I looked after us and by the time I was seven I could sew, cook and iron.

Tracy was 18 months younger than me and my only sibling. Most of the families in the area were bigger and I always wanted an older brother, someone to rescue me when I was in trouble. I thought about how together we’d go down the road and we would have a fight and stand together as a family – see, that’s the day-dreamer Pisces. Instead, my friends became the brothers I never had.

My mum herself had two brothers, Rodney and Tony. Tony was an army man and I idolised him – he was my first icon. His regiment was based in the Tower of London and, when we drove past there when I was a kid, I used to say, ‘My uncle lives in a castle!’ It was like a fairytale and I was so proud of him. I remember seeing him for the first time in the Tower with a tattoo on his arm of an eagle going through a cloud. He was a big influence in my life and I later ended up getting an identical tattoo to his.

Mum’s family were a big clan from Southern Ireland. My great-grandmother came over with 13 of them: five brothers and seven sisters, including my nan, Florence. Flo met my granddad, Gerorge Aves, over here. He was of Belgian descent – our ancestors had a Romany gypsy side and all of them had the dark hair and the green eyes: they were a good-looking family. Meanwhile, my paternal grandfather was Jewish mixed religion, which caused friction with the Catholic branch of the family.

I think Mum had a bit of anger in her; she rebelled against the faith and she was very impatient. She couldn’t handle me at all. Tempers run in the family – it must be all that Irish and gypsy blood. My great-grandmother, Nanny Kate, was in her seventies and she walked around with her cane that she’d swing at you. If you misbehaved in front of any of them, you’d get a clip round the earhole. My dad was more the calming influence. He’s lovely, my dad, he’s my best friend now, probably the greatest man I’ll ever meet, I’ve realised that as I’ve got older. But he was Church of England and when he married my mum that basically made her Protestant. Florence always wanted my sister and I to be brought up Catholic and we went to so many of their weddings and funerals, we practically were.

I was very close to nanny Flo and my other grandparents and great-grandparents. I was the first great-grandchild, I was the first grandchild and I was the first son, which in a large, extended family is a big deal and I was spoiled rotten by everyone. I liked staying in Flo’s house, even though going there meant I would be sleeping in a bed under the shadow of her crosses and gloomy pictures of the Virgin Mary.

I loved my granddad as well, at least the one on my mum’s side. I don’t even know the name of my dad’s father, the man who walked out on him. He saw me just once when I was a baby and then he went out of my life until I was 14 when he was dying of cancer and came over to pay a last visit to us. I barely spoke to him.

My granddad George was completely different. He was a park-keeper in Bermondsey and, when I was eight or nine, I got up early every Saturday to visit him in his park-keeper’s hut. Inside, we listened to the radio while I ate sandwiches. My granddad was nearly blind but he used to do all the flowerbeds himself and they were beautiful – he was brilliant. Those were some of the happiest times of my childhood.