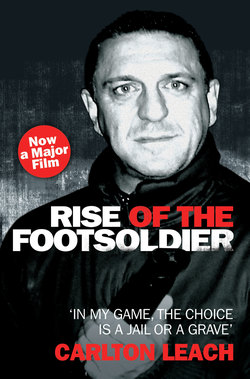

Читать книгу Rise of the Footsoldier - In My Game, The Choice is a Jail or a Grave - Carlton Leach - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Street Fighting Boy

I forced myself to get up. It hurt, but the one thing I’d had enough of was being pushed around by older boys at school. They were jeering, ‘Ain’t you had enough?’

I was 11 years old and starting to fight back – and I would never stop. I could easily have shrunk into myself, but that day I stood up and said, ‘That’s enough.’

The kid that started it said, ‘Right, after school,’ and we ended up going around the corner to sort it out. Before long, I was fighting boys two or three years older than me and I became very good at it, but to begin with I got into battles because I was teased about the way I looked.

I was very conscious of my image. My eyesight wasn’t great and I had to wear glasses from the age of seven. There were no designer glasses for kids in those days, it was either the round NHS specs or the ones I went for, Buddy Holly-style.

Kids are kids and you tended to get a bit of abuse at school, even at seven. It got much worse when I passed my 11-plus and went to Stratford Grammar, even though it was the best school in Newham and highly regarded throughout the East End.

By then I was aware of fashion. It was the era of the skinhead, the end of the Sixties. Ben Sherman, mohair, chinos, Dr Martens… but at school, we ran the risk of getting sent home if we didn’t wear flannel trousers and the regulation shirt and a tie. That was bad enough even without the glasses, particularly as I’d started noticing girls and they had started noticing me. So I sat at the front of the class where I could see the blackboard without my specs.

There were more geeky kids at this school than in other schools because it was a grammar – and that brought out the bullies. I didn’t like bullies then and I still don’t like them today. I began to be one of the targets, as did the school in general – it attracted trouble because it was the best in the area, with more intelligent people who had different ways of doing things. Needless to say, the other kids in the area didn’t like that.

By the time I was 13 or 14 I’d been fighting back for a while and I’d started to find myself and build a reputation. I looked more like I was 18 and hung around with older boys, which meant I could get into nightclubs where I would tell the girls I had a job. I left my childhood behind before it had finished. I could feel a new phase of my life beginning. I had learned to stick up for myself and I stuck up for my friends as well.

I had a couple of mates who I felt sorry for because they were bullied at school. They hero-worshipped me but it got a bit weird when I went out to buy some item of clothing and the next day they’d have the same thing: same make and same colour.

When I got to 15 I was supposed to take 14 mock O levels but I was far more into girls, bunking off school – often to see West Ham – clubbing and getting myself into trouble. It was the start of my rebellious phase and I became Jack-the-lad. The only exams I did well in were cookery, art, history and English language. I couldn’t really give a fuck about the rest of them. They should have given out O levels in fighting because I had established myself as one of the top boys.

I found my first real love that year with Theresa. We ended up having a kid while we were still just 16. In those days it was quite naughty and she had to take a break from school to have the baby. I really wanted to keep him, but her parents pressurised her relentlessly to give him up for adoption. They made her say that her education was more important and that she couldn’t give up her life. In the end I went along with it, telling myself that, if nothing else, at least we could stay together. I signed away my own son when I was hardly an adult myself. We had to fill out all the paperwork before she even had the baby. It was awful. Theresa was a week in hospital with him and I got to see him every day. Even the nurses were saying, ‘Oh, what a beautiful baby.’

I kept saying, ‘Keep him, Theresa, keep him.’ My parents were behind me and told us we could come and live with them and that they’d help to bring him up. My mum even said that she would give up the work that meant so much to her in order to bring him up while I went to work. Then the authorities came along and took him away. It was one of the saddest moments of my life. It was a long time ago, a different mentality then. I wouldn’t see him for another 25 years.

Theresa couldn’t stop crying. I thought it was the kid but eventually she told me the bad news. ‘My parents don’t want me to see you any more,’ she sobbed.

I was stunned. We’d been through so much. For the last three months of the pregnancy she had been hidden around at my house and she sneaked back home late at night – all so her parents’ neighbours wouldn’t see. I thought of everything that we had been through and I went mad. I ended up having a fucking big row with her dad and I offered him out. I thought it was really cold and callous.

‘Why can’t your daughter see me?’ I demanded.

‘’Cos you’ll make her pregnant again.’

‘Well, surely, after all we’ve gone through, she’s given the baby up ’cos of you. Wouldn’t it be better that she stays with the same person all her life? At least if there’s that one person, you know they’ll learn by their mistakes.’ But he wouldn’t have it. They stopped her seeing me. It was all fucked up.

We became secret lovers and I continued to see her for a long time. Then I met Karen and we fell in love. I wanted to get engaged. Even though I always loved Theresa and I wanted us to get back together again, all the creeping around was ridiculous. We’d been doing it for 18 months. I told Theresa it was over.

‘Oh, no,’ she said. ‘But I was going to tell me mum and dad that I’m seeing you.’ It was too late by then. I was 17, it was a couple of years down the line and the time had passed. Things with Karen were good, she was a really nice girl and I thought, I’m not going to fuck this relationship up. I didn’t want to be the bit on the side. I got engaged to Karen and I got a job down the docks.

You had to have a relative or know someone to work at the Royal Albert Dock. Luckily, Dad had a mate in the ship repairers Green and Silley Weir Ltd – their offices were where London City Airport is now. I had an apprenticeship lined up. My dad said I could be a welder, an electrician or a panel-beater – in the end I went for engineer.

‘That’s a good choice,’ said Dad. ‘Get your City and Guilds, get a trade, because you’ll always be able to fall back on that, whatever else you want to do in life.’ That was easy: the only thing I wanted to do was be a footballer.

I wasn’t bad as a kid. I played with Poplar Boys and we won our league. We got to go to West Ham and play a trial against their Colts, the kids who had already made it. It was my Pop Idol moment, only instead of performing in a glitzy studio in front of Simon Cowell, we played in front of West Ham scouts on a rain-soaked, muddy pitch at the Chadwell Heath training ground. It didn’t matter. I wanted more than anything to play for West Ham, even for a day – pull on the shirt and walk out in front of the crowd at Upton Park. Just imagine. It’s a dream I’ve never lost.

I usually played up front, but they told me to take fullback and I marked a kid a year older than me. He was unbelievable. He fucking turned me inside out. I was on my arse most of the game. I couldn’t get near him. He was playing midfield, coming down the right and he fucking slaughtered me. I trudged off the pitch and I knew that was my chance gone. His name was Alan Curbishley and he’s now the West Ham manager after a stellar career as a player. So I like to say that it’s Curbishley’s fault I didn’t get in. In reality, I know that, if I’d been that good, I’d have made it as a professional footballer anyway.

So I did my apprenticeship in the docks – and what a great life. The characters in the docks were proper old school, lots of comedians. I learned a lot in those four years of my life. I passed my City and Guilds and went to college for a year. I ended up as a maintenance engineer at Queen Mary’s Hospital.

I’d left home, bought my own house, married Karen and, with daughter Carly on the way, I subsidised my earnings as an engineer with door work. I never had big ambitions, I just wanted enough – but it wasn’t long before I realised that I could earn more money being a doorman than going to work seven days a week. My life was about to change in a big way.