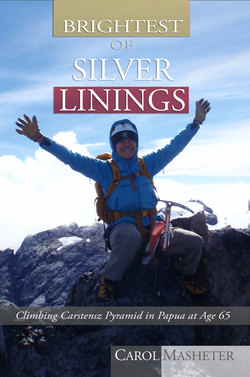

Читать книгу Brightest of Silver Linings: Climbing Carstensz Pyramid In Papua At Age 65 - Carol Masheter - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Off My Rocker

ОглавлениеI was furious. I paced in tight circles under a large gazebo near a cluster of posh shops and restaurants outside the gritty town of Timika in Papua, Indonesia. I had moved away from my companions to avoid spattering them with verbal acid. I had flown half way round the world at considerable expense to climb Carstensz Pyramid, a steep fin of limestone that rises to 16,000 feet elevation in mountainous jungle. After many delays and “guarantees” that failed to deliver, my companions and I had gotten nowhere near the mountain. The climb was over before it had begun.

I had heard that climbing Carstensz Pyramid could be challenging. Many things could go wrong and often did go wrong. However, lots of mountains are challenging. Take Mount Everest for example. Hundreds of people have died on Everest, since Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay summited it in 1953. Yet every year Everest lures hundreds more. As the highest mountain in the world, it has a certain cache, and many people have heard of it. Why, then, would anyone bother to climb a little-known, troublesome peak like Carstensz Pyramid? The short answer is the Seven Summits.

In the early 1980s a wealthy Texan businessman and amateur outdoorsman, Dick Bass, came up with the bold idea of climbing the highest peak in each of the seven continents, which he called the Seven Summits. However, some members of the mountaineering community have regarded the highest peak in Australia, Mount Kosciuszko at 7,310 feet elevation, as more of a hill than a mountain. The legendary mountaineer, Reinhold Messner, proposed that Carstensz Pyramid in Papua, Indonesia, a steep limestone fin of over 16,000 feet elevation, which he argued was the highest peak on the same tectonic plate as Australia, replace Mount Kosciuszko in the Bass list of the Seven Summits. In recent years increasing numbers of Seven Summiters have tried to climb the more challenging and inaccessible Carstensz Pyramid instead of Mount Kosciuszko. For additional details, please see the Appendix of this book and mountain guide Mike Hamill’s recently published book, “Climbing the Seven Summits.”

Why would a woman in her mid-60s who is afraid of heights risk life and limb to go to a troubled part of the world, like Papua, to climb a mountain? Why not stop with Mount Kosciuszko? Why climb at all? This book describes my reasons for wanting to climb Carstensz Pyramid, my preparation for the climb, the climb itself, and lessons learned along the way. It is based on entries in my travel journal as well as experiences as best as I can remember them. My companions may have experienced the same events and conditions differently.

I discuss some of the reasons for my involvement in high-altitude mountaineering in more detail in my first book, “No Magic Helicopter: An Aging Amazon’s Climb of Everest.” Briefly, when my life fell apart at age 50, I went to the Bolivian Andes for a break from the stress, loss, and anger I was experiencing. There I learned to climb and began to heal. I have learned some of the most powerful and valuable lessons of my life in the mountains.

One climb led to another. At age 60, I climbed Aconcagua, the highest peak in South America and my first of the Seven Summits. I had no plans to climb the entire list at that time, but the idea of climbing the highest peak in the Western Hemisphere intrigued me. Then I climbed Kilimanjaro as a test of a new fitness program I was using to prepare for trying Everest. Summiting Everest six months later was the happiest day of my life. When I returned home, a local TV reporter asked me, “You don’t look like the kind of woman who would be content to sit in your rocker. What’s next?” I mumbled something about the Seven Summits, more to have some kind of answer than out of real commitment. I was thin, tired, injured, and still getting my head around the fact I had summited Everest at age 61 and had survived. I thought I was done with climbing big mountains.

About three months later, after I had recovered from Everest, a strong urge to climb returned. I thought, why not try the rest of the Seven Summits? Denali in Alaska and Mount Elbrus in Russia followed. Three months after turning 65 years of age, I stood on the summit of Vinson Massif in Antarctica, my sixth of the Seven Summits. Only one more remained. I asked myself, would it be Mount Kosciuszko or Carstensz Pyramid?

What I had heard about Carstensz Pyramid both intrigued and frightened me. Certainly Mount Kosciuszko would be safer and cheaper. I was concerned about recent violence in Papua, the rigors of several days of strenuous hiking through mountainous jungle to reach Carstensz Pyramid, and the steep climb to its summit. However, I was not sure I would be content with finishing my Seven Summits with a hill instead of a mountain. Besides, since childhood, jungles have fascinated me. During my 20s, I signed up for a trip down a remote part of the Tana River in Kenya in dugout canoes. I imagined a Tarzan jungle with tropical trees and flowers, exotic birds, and chattering monkeys swinging through the forest canopy. However, the trip was cancelled. Maybe now, over 40 years later, was my chance to fulfill a longstanding dream to experience a jungle. Also, I am not proud of this, but I did not want others to say, “She couldn’t do Carstensz Pyramid, because it was too hard for a 65-year-old woman.” I decided to go for it.

In spite of its scary reputation, expeditions to climb Carstensz Pyramid tended to fill quickly. In the fall of 2011 I contacted Adventure Consultants, the mountain guide company with which I had summited several of the Seven Summits. This company’s guides had been supportive of me as an older female mountaineer. They knew me, and I trusted them.

I applied for a place on their expedition to climb Carstensz Pyramid in March, 2012. Applying for such a climb with a reputable mountain guide company is a bit like applying for a job. Applicants send their climbing resume, listing which climbs they have done with which guides. The purpose of the application is to screen applicants for appropriate skills, experience, and fitness level, so each applicant is an asset rather than a liability to the expedition.

Though I had climbed with Adventure Consultants before, I was nervous about whether they would accept me for this particular climb. A couple weeks later, notification of my acceptance arrived. I floated in a happy cloud of relief and anticipation, as I signed a contract and paid the expedition cost of 18,500 U.S. dollars (USD), which included climbing permits, payment for mountain guides and porters, transportation costs and some lodging expenses within Papua, food and cooking fuel for the hike through the jungle, and other local expenses. I was in!

In late January, 2012, I had returned from a wonderful climb of Vinson Massif in Antarctica. After a few days to recover from a cold I had caught near the end of that trip, I began to prepare for Carstensz Pyramid. With just five weeks before my departure for Papua, my preparation began with reviewing the Adventure Consultants gear list for the Carstensz Pyramid expedition. My gear for previous climbs was designed for very cold, dry conditions: a down sleeping bag rated to minus 25 degrees Fahrenheit for Everest Base Camp, a second down sleeping bag rated to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit for the camps above Base Camp and which I had used for Denali, Mount Elbrus, and Vinson Massif, a thick down parka and huge down pants that made me look and feel like a stuffed toy, and bulky, three-layer Millet mountain boots.

Most of this gear would not be suitable for the hot, humid jungle hike to and from the peak and a very long day of climbing, possibly in freezing rain and snow. The Carstensz Pyramid gear list specified a synthetic-filled sleeping bag rated to 15 degrees Fahrenheit rather than a down sleeping bag. I already owned several down bags. I was reluctant to purchase yet another bag with my dwindling funds, but I understood Adventure Consultants’ reasoning. When down gets wet, it loses its ability to keep a sleeper warm. Once wet, down is difficult to dry, especially in wet and humid conditions. Carstensz Pyramid was located in a jungle with daily rains year round. I found a synthetic-filled sleeping bag rated to 15 degrees Fahrenheit at Backcountry.com and bought it.

For clothing, I had suitable, lighter weight base layers and mountain boots, but I needed thinner climbing pants, jackets, and gloves. The equipment list also included two complete rain suits, the reasoning being that thorns in the jungle and the sharp limestone of the climb would shred our rain gear. I sold some of my old mountaineering gear and found most of what I needed at my favorite local climbing shop, IME in Salt Lake City. Polly Wiessner, an anthropologist acquaintance, who has done field work in Papua New Guinea, recommended Edgewater’s knee-high, insulated mud boots for the hike through the jungle, so I bought a pair online.

For my fitness program, I gradually increased my workouts to promote strength and endurance. At a local gym, I worked with free weights and did pull ups to strengthen my upper body. I used resistance machines to strengthen my abdominal muscles and legs. For endurance, I gradually increased the speed and distance of my runs. For the summit climb, I went to a climbing gym and practiced, first in rock shoes, then in the boots I planned to use on summit day, my La Sportiva Evo Nepal mountain boots. I took yoga classes for flexibility, balance, and core strength. I continued to ride my mountain bike around town, when the winter roads were not too icy. When the avalanche risk was not too high, I snowshoed and backcountry skied in the nearby Wasatch Mountains for longer training sessions. All was going according to plan.

I looked for flights from Salt Lake City to Denpasar, Bali, where I would meet the guides and the other team members. Using the Internet, I tried to find cheap round trip airfare. Even the fares on websites, like Travelocity and Expedia, were very expensive. I tried contacting travel agents who had helped me in the past, but they did not return my emails. I tried the Internet again, finally found a good buy, and bought my plane tickets on February 1. Pleased with myself, I checked off that task from my to-do list.

The day after I had paid for my airline tickets, Adventure Consultants emailed me. They wanted an additional 2,000 USD for the Carstensz Pyramid trip. Also, they had changed the expedition meeting place from Denpasar, Bali, to Timika, Papua, which would cost me at least another 1,200 USD in additional air travel. Perhaps some of the other expedition members had dropped out, so Adventure Consultants needed more money from the rest of us in order to run the trip. However, I did not have the additional 3,200 USD. I had retired from my last profession on January 1, 2012, in order to climb Vinson Massif and then Carstensz Pyramid. I had paid for both climbs, while I was still working. As a new retiree, my retirement income had not started. I was living off financial fumes.

I asked Adventure Consultants for other options. Very graciously, they mentioned that Mountain Trip, a company based in Ophir, Colorado, was also running a Carstensz Pyramid climb in early March, 2012. I had not heard of Mountain Trip, so I Googled them. Bill Allen, one of the company’s owners, had run six Carstensz Pyramid trips in recent years. On five of those trips, expedition members had summited. Their safety record looked OK. Their Carstensz Pyramid trip was shorter than Adventure Consultants’, 14 instead of 17 days, but the price was the same. Mountain Trip’s expedition cost included the flight from Denpasar to Timika as well as helicopter access to the base of the actual climb, avoiding the strenuous jungle hike.

I was surprised. Several other mountain guide companies had provided helicopter access recently, but they now claimed that such access was unreliable, and they no longer offered it. A few other climbers I knew had hired drivers to take them through the Freeport Mine. However, access to the Mine road has been controlled by a complex and unreliable web of influence. A guide friend of mine tried to sneak through the Mine a decade ago, was caught, and held prisoner in a large metal container. He escaped, was recaptured, and eventually had to pay a substantial bribe for his freedom. Driving through the Mine did not seem to be any safer or more reliable than helicopter access.

For the next few days I weighed the pros and cons of Mountain Trip’s Carstensz Pyramid expedition. Part of me balked at the helicopter option. I had psyched myself up for Adventure Consultant’s jungle hike. I had already bought special mud boots and had been training for the hike. Flying in a helicopter from Timika at sea level to Base Camp at nearly 14,000 feet elevation would not provide the gradual acclimatization of walking several days through the jungle to Base Camp. Climbing another 2,000 vertical feet within a day or two after arriving at Base Camp would be at best very strenuous and at worst put members of our team at risk for altitude sickness. Also, daily rain storms and rugged terrain made flying dangerous, especially for helicopters.

On the other hand, flying by helicopter was seductive. The flight to Base Camp would avoid rumored dangers of the jungle hike -- the possibility of being kidnapped by tribal warriors, porters going on strike and abandoning us, being injured or becoming ill in the jungle, to name a few. Also, the jungle hike to Carstensz Pyramid Base Camp sounded really strenuous. Maybe I had done enough strenuous things in my life. Now that I was nearing age 66, there was no shame in taking the easier way to the mountain, I told myself and my friends. Besides, I had never flown in a helicopter and wanted to see what it would be like.

The positive aspects of the Mountain Trip expedition outweighed my concerns. A few days after I sent my application for their Carstensz Pyramid climb, Mountain Trip accepted me. Adventure Consultants graciously transferred what I had paid them to Mountain Trip. Frustration and anxiety shifted to happy relief. I was back on track to climb Carstensz Pyramid.

Within a few days Mountain Trip sent me a list of names and email addresses of the guide and two other client climbers. Mountain Trip suggested that we contact each other and tell a little about ourselves. This seemed like a good idea. I composed a short email, hoping I sounded friendly and competent but not too cocky. I pictured the guide and the other climbers as being leaner and younger than myself. I hoped I would be able to keep up with them. Kevin Koprek, our expedition leader, and Carina Raiha (pronounced KahREENa RYEya), the other woman climber on the trip, each sent friendly replies. I received no reply from the other climber, Dennis Uhlir. Perhaps he is busy getting ready for the trip, I told myself, but I felt a little rejected.

I looked up each of the team members on the Internet. Kevin had experience with high-angle rescues, skills I found reassuring for our steep climb. Carina was the first Norwegian woman to summit Everest. Dennis had summited Everest recently with Adventure Consultants. I looked forward to meeting them and sharing our Everest experiences. Our guide and my fellow climbers seemed well qualified to climb Carstensz Pyramid.

A couple of weeks later the Mountain Trip staff asked whether I wanted to share a hotel room in Bali and Timika with a newly added, fourth member of our team, whom they described as a young man from Malaysia. Sharing a room with a stranger sometimes works, but it sometimes does not. If he had different expectations than mine about what sharing a room meant, that could be awkward. Since I had not yet met him, I decided against it. I scraped together another 400 USD and paid Mountain Trip for a single supplement, so I could have my own hotel room.

As departure day approached, emails from Mountain Trip changed in tone. While they still seemed confident that they could provide helicopter access, they advised us to come prepared for the jungle hike as Plan B. Fine, I thought. I had been running, bicycling, snowshoeing, and hiking in preparation for the possible jungle hike. I already had knee-high mud boots. I would bring them in case we went with Plan B.

March 1, 2012. Today was the day before departure day. My former colleague, Tom Hudachko, had released a news advisory about my goal to become the oldest woman in the world to climb the Seven Summits. Tom had suggested that I be available for interviews from 4 to 5 p.m. at my home today. I was not sure what to expect, but I tidied up the usual chaos that takes over my house, when I am packing for a foreign trip. Just before 4 p.m. a reporter with a scraggly, gray pony tail and big belly showed up. He asked me to sit in my rocking chair, something I never do, while he asked me questions and videotaped my answers. He had me hold up some of my climbing gear and a copy of my first book for the camera.

In contrast to my previous encounters with reporters, this guy seemed uninterested and just going through the motions. I told myself, one bored reporter is better than no reporters. I compensated for his low energy by answering his questions with extra enthusiasm. At least I’m having a good time, I tried to convince myself, but in fact I felt awkward and a bit silly. This is the unglamorous side of being “a little bit famous,” I thought wryly.