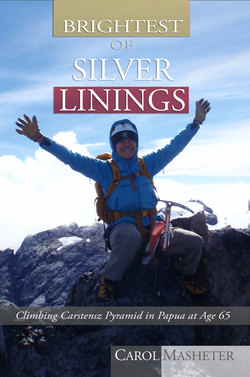

Читать книгу Brightest of Silver Linings: Climbing Carstensz Pyramid In Papua At Age 65 - Carol Masheter - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Blessings in Disguise

ОглавлениеBack home in Salt Lake City I tried to reframe my disappointment and frustration about the aborted Carstensz Pyramid climb. If the other team members and the guide had been so reluctant to try the jungle hike, perhaps they had saved me from myself and my compulsion to complete a project, I reasoned.

A few weeks later Mountain Trip refunded less than half of what I had paid them. My anger bubbled up again, pulling me back into frustrations I had just started to move past. Mountain Trip claimed they had had “expenses.” I was sure the trip had cost them something, but I did not see how these “expenses” could add up to 9,500 USD. I considered suing them. However, I did not want a reputation among mountain guide companies as a trouble maker. I was angry, but I was also ready to put this experience behind me and try to find another Carstensz Pyramid expedition to join.

I learned that Adventure Consultants was planning a Carstensz Pyramid expedition in August, 2012. When I emailed them, they replied that their expedition was already full, but they could put me on a waiting list. This was too ironic. Their March trip had collapsed, after climbers had dropped out. Now I could not get on their August trip.

I wanted more certainty than being wait-listed, so I did an Internet search for other Carstensz Pyramid expeditions. International Mountain Guides (IMG) had a Carstensz Pyramid expedition beginning in early July, 2012. I had climbed both Aconcagua and Kilimanjaro with IMG in 2007. Both climbs had been good experiences. When I emailed IMG, they said they had room for me on their July Carstensz Pyramid expedition. I was back in the game!

IMG offered only the jungle hike option. Like Adventure Consultants, they had tried the helicopter option and had found it to be too unreliable. IMG described the jungle hike as a “real adventure.” On my March trip to Papua our guide’s descriptions of the jungle hike’s dangers had filled me with dread. Yet pictures on the IMG website intrigued me. Images of exotic forests, their trees furred with emerald green moss, climbers caked with mud grinning for the camera with barefoot Papuans fanned the embers of my decades-old dream of having a jungle experience. Clearly, IMG’s marketing of the jungle hike worked on me.

With only three months to prepare, I got right on it. I sold enough mutual funds to pay for the IMG expedition. I found airline tickets to Denpasar, Bali, where the expedition members would meet, at a good price and bought them. I read IMG’s training notes written by Jason Edwards, who had led several Carstensz Pyramid expeditions via the jungle hike. Jason wrote:

“Think of Carstensz Pyramid as the ultimate CrossFit or adventure challenge course in the world....we will jump, leap, slip on roots, drop suddenly hip deep into mud, have to balance on 30 foot historic stick bridges, which present opportunities for unexpected twists, strains, over-stretching, and various soft-tissue injuries. Being flexible is one of the most important things you can do to prepare for travelling through this kind of terrain.”

My anxiety began to resurface. I was not sure my 65-year-old body was up to the challenges Jason described. I had a bit of wear-and-tear arthritis and tendonitis in my knees as well as facet arthritis in my lower back. My balance and agility had diminished over the years. Deterioration in my depth perception had compromised my ability to estimate distances, especially while down climbing and jumping across gaps. Would I be able to keep up with the rest of the team through the jungle? I wondered. Are my rock climbing skills good enough to reach the summit?

Jason’s experience gave him a lot of credibility, so I took his training suggestions to heart. To counter my anxiety, I trained regularly at a local gym and increased the difficulty of my workouts. I added an agility drill of my own design to help prepare myself for the jungle hike. At the gym I set a bench-press bar crotch high, then practiced climbing under and over it as quickly as possible, first in my running shoes, then in my mud boots and while carrying my climbing pack loaded with increasing amounts of weight.

For the summit climb I sharpened my skills on actual rock. Starting in late spring, when my friends started climbing outside, I joined them. My climbs were embarrassingly awkward and unskilled. I was shocked by how much I had forgotten about climbing rock, something I had done regularly a decade previously. What had happened? How had my skills deteriorated so much? Duh, I reminded myself, when I had not practiced speaking the little French, Spanish, or Hindi I knew, it had slipped into less accessible corners of my mind. Why would rock climbing be any different? I realized that the opportunity to climb outside on rock before another try at Carstensz Pyramid could be a blessing in disguise from the failed March trip.

My climber friends were patient and did not seem to judge me, as I crept timidly up easy climbs. When climbing once a week did not improve my skills, I hired Anna Keeling, a local, certified mountain guide. Anna and I were about the same height, but she was leaner, more muscular, stronger, and at least 20 years younger than I. Though I was fit and strong for a woman of my age, next to Anna I felt like a weakling with too much fat around my middle. Friends later told me that Anna was a nationally rated mountain bike racer and expert skier who certified other professional guides. She was too modest to mention these impressive accomplishments.

Anna was patient with my hesitant climbing. On one steep wall, I gouged my knee, as I lunged for a hand hold. The knee bled, dripping down my leg and onto the rock face. It was not serious, just messy, but that day it freaked me out. I froze, unable to get my mind in gear and find holds I could trust. My anxiety grew from a dull buzz to a shrill scream inside my head, I’m scared, I can’t do this, I hate climbing, why am I doing this!? Though I had not said a word aloud, Anna read me like a book. She called down, “Carol, you have to get your game face on and just do it.” She was right. I clinched my teeth and made a move, then another, and another. It wasn’t pretty, but I got up that climb.

Over the weeks, my confidence waxed and waned like some kind of weird moon. During the waning phases, I felt unqualified to climb Carstensz Pyramid and wondered whether I had been nuts to sign up for it. During the waxing phases, I told myself, I just need to tell the negative self-talk to shut up and get on with my training. A new climbing friend, Ellen Leis, and Anna both said my climbing was slow but okay. Their assessment helped prevent my self-doubt from overwhelming me.

My short rock climbs helped refresh my skills, but I needed a dress rehearsal for the long day of climbing on summit day. I wanted to practice wearing the leather belay gloves and the mountain boots I planned to use on Carstensz Pyramid, which would be too cold to climb with bare hands and light-weight rock climbing shoes. The West Slabs on Mount Olympus in the Wasatch Mountains near where I live was a logical choice. Though this route was rated only 5.5 according to the Yosemite rating system, and was easier than the normal Carstensz Pyramid route, the West Slabs ascends 1,600 vertical feet and could take all day, like Carstensz Pyramid. About two weeks before I left for Papua, I arranged to climb the West Slabs with Alex LeMieux, another local, certified guide, as Anna had already left for New Zealand, where she, her husband, and their young son lived for six months of the year.

Alex and I started early in the morning. Our approach to the climb involved a bit of bushwhacking and route finding. After a couple of minor wrong turns, we scrambled up a shady couloir (a narrow, mountainside gully) with patches of hard, steep snow, then to the base of the climb, where we each tied into a 60-meter rope. What I could see of the route looked less steep than it appeared when viewed from the valley floor. Much of it had cracks and edges for feet and hands, yet some sections looked quite smooth. As Alex and I began our climb, I was not sure whether my mountain boots would stick to the smooth rock.

Alex led the first pitch, while I belayed him. A pitch is a section of the climb, up to the length of the rope between climbers, to a safe place, where the lead climber can belay the following climber. Belaying is a technique of managing the rope to protect a climbing partner during a fall. When it was my turn to climb, I was pleasantly surprised how well my boots stuck to the rock, even when I used only the very tips of my toes. I felt like a ballerina en pointe creeping up the rock. On subsequent pitches, I looked for smaller holds and steeper lines to test my boots’ limits.

After our 10th pitch, Alex and I untied from our rope, coiled and loaded it into his pack, and scrambled up to the ridge. The summit was not much further up the ridge’s spine to our left, but we each had summited Mount Olympus many times before, so we decided to descend, before it got too late.

We rappelled down the slabs. Alex scrambled down first to locate the first rappel anchor, a sling around a big tree with a steel ring through which to thread our rope. Rappelling is a technique in which the climber backs down a steep rock wall, feet flat against the wall, while controlling the feed of the rope through a friction device attached to the climber’s harness. Alex, then I, managed each of several successive rappels smoothly. We were scrambling down the couloir off rope, when I slipped and lost my foot holds. Hanging by my fingers from a rocky ledge, I froze, paralyzed with fear. Alex helped me get my feet back on the rock, so I could climb down safely. I felt like a fool, but Alex did not treat me like one. Even after that embarrassing moment, I was pleased to have climbed the entire day carrying a climbing pack and wearing the boots and gloves I planned to use on Carstensz Pyramid.

The IMG training guidelines suggested hot yoga to increase core strength and flexibility. In recent years heat and humidity had made me feel weak, unmotivated, and even unwell, so I had avoided trying hot (or Bikram) yoga, though several friends had enthusiastically recommended it. During my last practice climb with Anna, she told me about a special deal at a local yoga school, 10 continuous days of Bikram yoga for 20 USD. I decided to give it a go. Twelve days before I left for Bali, I signed up.

While I was still employed with the Utah Department of Health, I had practiced YogaFit yoga regularly for about seven years in our in-house fitness room. I had even taught a basic yoga class there once a week for two years. YogaFit teaches us to be patient and kind with ourselves. I had found the gentle, YogaFit approach to be a beneficial counterpoint to the traditional, no-pain, no-gain fitness training I had used for decades.

At my first Bikram yoga class I made a timid entrance. Very lean guys wearing only fitted black trunks padded barefoot in the lobby. I felt self-conscious, as I wrestled my yoga matt, towels, water bottle, and gym bag into the semi-dark studio. Heat hit me like a blast furnace. In a rear corner, I stripped down to sweat band, jog bra, and running shorts, resisting the urge to compare my aging body unfavorably to the bodies of lithe, younger yoga practitioners. Sweat ran from every pore, trickling through my hair, down my chest, back, arms, and legs. Let it go, I coached myself. You have sweated before. Not this much, my inner whiner whimpered, as sweat saturated my sweat band and poured into my eyes. Other practitioners were lying on their backs with their eyes closed on their mats. That looked like a good idea, so I did the same.

Lying there staring at the ceiling, my usual pre-yoga meditation took over. I relaxed, deepened and slowed my breathing, and quieted my mind. Curiosity replaced some of my anxiety. What would this first Bikram yoga class be like? What would I learn?

Suddenly someone opened the studio door. Bright lights came on and stung my eyes. A male voice rang out. “Welcome! I’m Stan. Stand up! Is anyone new to Bikram yoga?” I scrambled to my feet and timidly raised my hand along with a couple others in a sea of experienced practitioners. “Follow along, and do what you can,” Stan advised us. “If you need to, stop and rest a moment.” I can do that, I thought. I relaxed a little.

Then we began. Unlike YogaFit classes, which consisted of long, slow flows accompanied by the instructors’ gentle coaching, “If it hurts, don’t do it; don’t bounce, don’t lock your joints,” Stan barked militaristic commands, “Bend back, way back, fall back; now bend forward, more, lock your joints, more, bounce! Lock your joints!” Stan signaled the end of a pose or stretch with a sharp hand clap like a gun shot, which made me flinch.

Within minutes, sweat stung my eyes and blurred my vision. I thought my eyeballs would drown. I clawed sweat from my face at every opportunity simply to see. When I tried to stand on one foot, lift, and grab the other foot as instructed, my foot slipped out of my hand like a greased fish. The constant drip, drip, drip of my own sweat drove me nuts. Let it go, it’s only sweat, I reminded myself repeatedly.

Several times I was tempted to stop and rest, but I took a deep breath instead and kept going. Finally, all the poses, flows, and breathing exercises were done. Lying on my sweat-soaked towel in final relaxation pose, I felt a quiet sense of triumph. I had survived my first 90-minute Bikram class. I would be back tomorrow. As the days passed, the classes became not easy, but easier. My flexibility improved more than I expected in such a short period of time.

Meanwhile, IMG emailed a link to a video of Papuans demonstrating for more autonomy from Indonesia (see www. youtube.com/watch?v=2qonI4-5iA8). The video showed large parades with some Papuans wearing tribal regalia and carrying traditional spears or bows and arrows. Others carried separatist flags and banners. Though the parade appeared to be peaceful, the video was unnerving, as Indonesia had a recent history of ruthlessly suppressing even peaceful demonstrations like this one. The political situation was out of my control, so I tried to focus on factors I could control, like my fitness training, to prepare for this trip.

Time sped up and slowed down erratically, as my departure day approached. Unexpectedly, John Pieper with Gregory, a locally owned company that makes packs, found the only size small of a canary-yellow, 50-liter Alpinisto climbing pack in North America and got it to me before my departure day. I had admired Alex’s copy of this pack, when we climbed the West Slabs on Mount Olympus. Alex must have told John about me. This new pack was perfect, as our Carstensz Pyramid guides wanted us to wear bright colors in the jungle, so we would be easier to see in the dense, dark foliage. I was delighted and grateful for John’s last-minute gift.

June 29, 2012. I woke up early, unable to sleep. The first of my series of flights from Salt Lake to Bali was in the evening, so I had the day for last-minute preparations, before the airport shuttle picked me up. I rechecked and repacked my gear for the last time, trying to get my jungle hiking and climbing gear down to the 44 pounds we would be allowed for the final flight from Timika to Sugapa. I failed spectacularly. My gear weighed 97 pounds. Why do mountain guide companies do this? I grumbled. They insist we bring every item on their equipment list, but then my baggage always weighs too much. On past trips, the guides had helped me decide what to bring on the climb and what to leave behind during the gear check, before we left our last hotel. That thought eased some of my annoyance and anxiety.

I would carry my mountain boots and knee-high mud boots in my new yellow climbing pack as my carry-on bag. To conserve space, I stuffed each boot with other items that would be difficult to replace if lost, such as my prescriptions and digital camera. Around the boots, I crammed my journal, a small bag of toiletries, passport, cash, travel documents, and debit card. Everything else, I divided evenly between two duffels, so if one went missing, all items of a particular kind would not be lost.

To calm my pre-departure jitters, I went to my gym for a short, easy workout. There would be few opportunities to exercise during the long flights and lay overs in airports. After a light lunch, I picked spinach from my garden and gave bags of it to my neighbors. I watered my lawns, vegetable garden, and fruit trees one last time. I tried to nap, hoping to stockpile sleep before the trip. No luck. I kept remembering things that needed to be done and jumped up to do them. I had to smile at this familiar pattern of pre-trip restlessness. I was turning down the air conditioning, when the airport shuttle pulled into my driveway. I shouldered my climbing pack and grabbed my two duffels, wrestling them through the front door into the hot, summer evening. Preparation was over. The trip had begun. A familiar sense of relief swept over me.