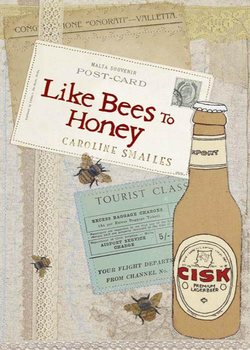

Читать книгу Like Bees to Honey - Caroline Smailes, Darren Craske - Страница 12

Sitta

Оглавление~six

Malta’s top 5: About Valletta

* 1. The Knights of St John

Valletta is indebted to the Order of the Knights of St John, who originally designed the city as a sanctuary to tend to wounded soldiers during the defence of Malta against the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century. Before this, the order was situated in a little watchtower, named St Elmo, the only construction on Mount Sceberras, which lies between two harbours. The valiant conqueror of the Great Siege, Grand Master La Valette, understood that for his order to uphold its grip on Malta they would have to build sufficient fortifications. A plan was devised for the fortified city which was given the name Valletta, in honour of La Valette.

The air steward’s voice is monotone, floating over the bustle of the tourists.

‘Please stay seated until the aircraft is stationary.’

They do not, of course.

within the minute the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal is heard.

People stand, push into the aisle, pull coats and bags down from the overhead lockers.

The stairs are being attached. The door opens.

I squeeze into the queue in the aisle, clutching my handbag and my shawl to my chest. Christopher follows, pinching in behind me, invading my personal space, again. We do not move.

I am impatient.

I want to be off the plane, I need to be in the open space, breathing in the dust of Malta. I want to scream. I want to tell the tourists to move out of my way.

We begin to move.

We take small steps, we shuffle; I do not let other passengers step in front of me. I avoid eye contact. I ignore the pregnant woman, I ignore the goodbye from the air steward; I walk down the metal steps.

the heels of my boots clip clap.

~cl – ip.

~cl – ap.

~cl – ip.

~cl – ap.

but there is no blast of heat, no warmth from my Lord’s smile, not today.

the heavens are spitting, spatting.

~sp – it.

~sp – at.

~sp – it.

~sp – at.

I lift my face up to creation. The sky is grey, sullen, moody.

His rain falls onto me. He spits on my face.

My Lord blesses my soul.

Merba.

~welcome.

I walk in my Lord’s spit, following the trail of people, staying in between the yellow guide lines that direct into arrivals. We are close to the terminal, no bus is needed.

I hear the engines thrusting their whirs.

they whirl.

~wh – irrrr.

~wh – irrrr.

~wh – irrrr – llll.

The airport is calm, quiet. I wait for my suitcase to churn around on a conveyor.

I feel a chill. I shiver shiver, shiver shiver.

My bones are cold.

The airport smells of popcorn.

I am hungry; the sweet airport air has increased my need. I cannot remember when I last ate. My stomach churns. I am famished in Malta.

I lug, I wheel my suitcase. I do not collect a metal trolley.

I walk through customs, nothing to declare, I step onto the escalator. I travel down, slowly. I look onto the crowd that stands waiting for people to arrive. My eyes search, in vain.

I walk, I stagger through the crowd and out, into His rain.

I queue for a taxi.

Christopher follows, several steps behind me. He does not speak.

We are in a taxi, going to Valletta, my suitcase is in the boot. It will take twenty-five minutes, I think. We are going to my mother’s house, home. I dwell on the word home.

I long for a home.

I watch through the taxi window; the island rushes, blurs past my eyes with colours, with whites, with greens. The sandstone constructions are greying through the drizzle, they look weary, lost. I watch cars slip and slide past us, some are shiny, promising wealth and importance; they dance in the rain. We travel along a new road, an unknown journey. I search for familiarity, I need familiarity. I could be anywhere, any Mediterranean country, any foreign soil.

I seek acquaintance, for something to connect me to my roots. My eyes rest on golden arches, McDonald’s.

Time has altered my island.

‘John Lennon lives in Malta.’

My son says. I laugh, ha ha ha.

‘Oh Christopher! Who told you that?’ I say.

‘Jesus did.’

My son tells me.

‘I’m hoping to meet with Jesus,’ I say.

The taxi driver looks in his rear-view mirror, his dark eyes meet with mine. I smile at him, I raise one eyebrow. He looks away, quickly, back to the road.

‘Geordie shares Cisk with him in Larry’s bar.’

~Cisk lager was first available in Malta in 1928. It has an alcohol content of 4.2 per cent.

‘Geordie?’ I ask.

‘Elena’s husband.’

‘Elena?’ I ask.

‘Geordie’s a spirtu, a spirit, like me. He’s waiting for Elena to pass over. She’s your mother’s aunt, lives in Newcastle.’

Christopher is right. I recall, the words connect, ignite.

I have heard the stories of Elena, the family shame, the ostracism. She met Geordie, an English soldier in Malta, during the war. The family rejected her union. I do not know the full story. I know only fragments.

‘Geordie told me Jesus sent me back to help with your grief.’

My son breaks my thoughts.

‘Well his plan backfired, didn’t it?’ I say. ‘And I’ll tell him so when I see him.’

The taxi driver tuts.

Christopher does not speak for the rest of the journey. We travel in silence. The taxi driver switches on the radio; it crackles, interference. I hear a voice, loud, clear, through the rustles, through the static.

Jesus: Welcome home, my Nina.

The taxi driver does not speak.

I am unsure if my mother knows of my arrival. I suspect that Christopher may have told her. He tells me that he visits her, often.

He tells me that he can do that.

He says that he can be with different people, in different places, at the same time.

He tells me that he is like God, but very different. He tells me that he is like God because God can also be in so many different places at the same time.

I believe in Christopher more than I believe in my Lord.

The taxi drops us outside of the walls of Valletta. The driver keeps his eyes down as he speaks of the money that I must pay.

I fumble with my purse, with my euros.

The taxi driver does not move from his seat. He presses, something, inside of the car. There is a click. The boot springs open, slightly. The taxi driver waits, in his seat. I struggle with the boot of his car and then with my suitcase.

Christopher has not the strength to help me.

I wobble with my suitcase.

~cl – ip.

~cl – op.

across the bumpy pavements.

I am clumsy, I walk.

I walk through the City Gate and into Valletta, il-Belt.

~the City.

My heeled knee-length boots feel awkward, clumpy.

The roads and the pathways of my Capital, of Valletta, are uneven. I wobble over them; I am cautious, fearful of falling. Malta could never be smooth, perfect without blemish, there is too much history, there are too many marks, injuries, scars. Today, I am fearful of the cracks swallowing me.

I walk, gracelessly, slowly, as the Renaissance streets open up before me.

I.

~cl – ip.

~cl – op.

along the side of the road, pulling my suitcase behind me, watching my son lead the way.

Last time I walked these cobbles I was with Matt and with my five-year-old Christopher. The memory stings. I remember our walking through the City Gate and into Valletta. I remember the blistering warmth. I remember that Christopher was tired, the early morning journey and the high temperature were taking their toll. I remember Christopher was dragging behind us, no hand to hold, no comfort to be found. I remember Christopher asking me why the Opera House was broken. I remember ignoring his question, walking up again, then down again. I remember that it was busy, packed with tourists wearing as few clothes as possible, yet still dripping in sweat. I remember that Christopher moaned with each step. He wanted to go home. I remember that Matt did not complain, that Matt never complained.

I look up, I feel His spit on my skin. I look to the buildings. They embrace the past, leaning to me, crumbling, neglected. The details speak of disregard, of bombardment.

I turn right, I.

~cl – ip.

~cl – op.

past the broken down Opera House, up again.

‘It was bombed,’ I tell Christopher.

‘I know, Nanna told me.’

He says.

I turn, left, down again. The course is familiar, instinctive, unchanged. I have walked this route before, alone, with others, with my sisters, with my mother, with my father, with cousins, with Matt, with Christopher.

All streets slope down to the harbour.

It is morning, spitting, cold and busy. Tourists still visit in February.

I bump my suitcase down each of the stone steps, making my way down the slant of the steep street. The roads are narrow, the buildings tower, built to provide shelter from the overpowering heat of the summer. Today they would say that it rains lightly, I would say that my Lord spits, but the narrow streets of my home offer protection, of sorts.

I am wet, cold in my bones, shiver shiver, shiver shiver.

I reach my mother’s green front door.