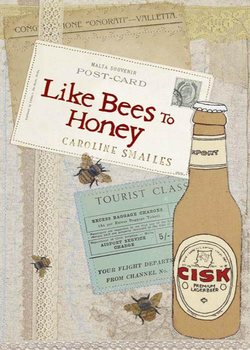

Читать книгу Like Bees to Honey - Caroline Smailes, Darren Craske - Страница 8

Tnejn

Оглавление~two

Air Malta is not only committed to provide you with a comfortable journey, but also to give that extra personal touch…

The doors have been closed, security measures have been explained. I did not listen or watch. Christopher is virtually on my knee, squashing in between me and the passenger next to me. He is fidgeting, wriggling, annoying.

‘Sit still,’ I tell him.

He looks at me but does not speak. We both know that the plane is ready to lift us from that ground.

the engines are whirring.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

and as my head falls back to the headrest, the engines whir some more.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

then the plane darts forwards, upwards, it tickles into the back of my throat. I swallow, forced gulps.

I look out through the small oval window, the houses and cars become insignificant. I see the clouds. I am flying over the clouds. I am flying over a blanket of greying white that separates and joins. I am in the air, higher and higher.

And then I realise.

I am gone from his England.

I wrap my large shawl around my shoulders. I bring the two ends together, up to my face. The shawl has tassels, the tassels tickle me, annoy, remind me. I wore this shawl when Molly was a baby, before she began toddling. I can remember her curling into me, fiddling with the tassels, rolling them between her tiny plump fingers, pulling them up to her mouth.

I want the smooth material close to my face.

I am sobbing.

~s – ob.

~s – ob.

~s – ob – bing.

into my shawl.

I am dripping.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip – ping.

snot and tears into my shawl.

The plane continues to move higher and higher above the clouds. I continue to sob, muffled sobs.

I have become the flight maniac. I want to apologise to the passenger beside me. He is dressed in a casual suit, creased slightly; his shoes are shiny, polished and buffed. I want to tell him about my life and my loss, but I do not. Of course I do not.

I am the flight maniac.

telling him my story, loudly, over the sound of the whir.

~wh – ir.

~wh – irr.

whirling engine, would only make things worse.

And so I continue to stifle my sobs. And the passenger beside me turns away, his left shoulder protruding, twisting awkwardly.

Christopher does not speak. I think that he may be sleeping.

The seatbelt sign goes off.

the plane is filled with the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal.

And within the minute, there is a queue for the toilet, four men and one woman line from the drawn curtain and down the centre aisle. She looks pregnant, the woman. Her stomach is large, egg shaped; her palm is resting on it. I wonder if she is having a girl or a boy.

I want to talk to her. I need to talk to her. She must be able to smell food.

I really should buy her food.

I grew up on the island of Malta, in a close neighbourhood, with open window and open door. The community liked to cook and the odours of our foods were rich. They decorated, they floated in the air, breads, sweet pastries, baking potatoes, spice-filled macaronis, soups that celebrated local vegetables. This meant that a pregnant woman, whoever she might be, would smell the food and that with that smelling her baby would feel a desire, a need. And so, in Malta, without request, all from the community would know to take a dish of any food being prepared to any pregnant neighbour. It was almost a law, I think. It is said, in Malta, that the food will feed the desire of the baby. If a pregnant woman does not have, does not eat all that her baby craves, then it is said that the child will be born with a birthmark, a mark with a suitable shape.

I remember that my mother had a notebook.

She would write down the names of our pregnant neighbours and I remember that when one of our neighbours was heavy with her fourth child, my mother, she told me, ‘Nina, listen, take this to Maria.’ She told me, ‘I do not like her but her baby must have what it desires. Take her this.’

I remember looking down to see my mother holding a dish of minestra.

~a vegetable soup containing local or seasonal vegetables, potatoes, noodles.

We had many mouths to feed with our daily food, yet still we would feed a baby of a neighbour. The bowl was hot, my mother’s vegetable soup sloshed as I walked down the slope to Maria’s house. I remember that it was summer, the tall houses sheltered from the burning sun, the cobbles were cool under my naked feet, the dust swirled from recently brushed doorways. The smell of the minestra, so rich and sweet, danced and twisted up my nostrils. I remember the liquid spilling onto my fingers, burning and my longing to taste the food, but, of course, I would not, could not even. I had learned not to deprive a baby; I could not even lick my fingers. I remember walking the cobbles, slowly, slowly down the slope and I remember Maria answering the door.

She told me, ‘I will not eat the food of your mama’ and then closed her front door, with a slam. I knew better than to return home with the minestra and so I left the bowl to the left of her step, where she could not trip over it. And I shouted loudly, told Maria that her baby’s food was outside.

Three months later my mother told me, ‘Nina. Go look. Maria’s baby has the mark of a broad bean.’

I stare at the swollen stomach of the tourist on the plane. The queue is slow. She is leaning now, against an aisle seat. I look to her face. She is young, she appears tired.

I remember how tired I was when pregnant with Molly.

I push Christopher off me, slightly; he continues to sleep. I stand, place my shawl onto my seat and walk to her. I do not like walking on planes. My feet seem too light, like I have marshmallows on the tips of my heels. I squish my way to her.

I reach her.

‘Are you hungry?’ I ask.

‘Sorry?’ She looks frightened.

‘Can you smell food?’ I ask.

‘Sorry? No. Please.’ She is frightened.

‘You must eat whatever you smell,’ I say.

I turn, I walk from her, squishing my marshmallow-tipped heels, not looking back. I find my seat.

I move Christopher to one side; I sit.

I look to the pregnant woman. She is talking to the man in front of her; they are looking at me. She is full of fear. I need to reassure her. I know that she is frightened, but she must eat.

I mouth words to her.

I mouth, do not worry.

I mouth, I do not have the evil eye.

I mouth, you must eat what you smell.

I wonder what shape birthmark her child will have.

and then I realise that I have started.

~s – ob

~s – ob

sobbing, again.

I really am the flight maniac.

I have woken Christopher with my moving about, with my sobbing.

‘Iwaqqali wii l-art.’

~you embarrass me/you make my face fall.

I stare at him, stopping my sobbing, allowing tears to trickle and snot to drip, but no sound.

‘Iwaqqali wii l-art.’

~you embarrass me/you make my face fall.

‘Who taught you that? Who taught you that?’ I demand.

‘It’s ilsien pajjii.’

~mother tongue.

‘How? Tell me how,’ I demand, again.

Christopher does not answer.

The small television screens come down, a graphic of a toy plane is edging slowly over the UK, heading South. The air steward tells us that headsets can be bought, the film starts. Live Free or Die Hard, I am glad that I cannot hear the words. Christopher is watching the screen.

A child, across the aisle, says, ‘For fuck’s sake.’

I turn. He is twelve, maybe younger. His mother smiles at me, briefly.

And I think of Molly, again.

tears drip.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip.

again.

It is nearly 6 a.m. I think of her getting dressed. I wonder if Matt will send her to school. I think of her hair and of how Matt cannot manipulate bobbles, cannot bunch or plait. He may use the wrong brush, tug at her tats, not hold the hair at the root. I think of her crying out with pain.

I think of the mums in the school playground, of how the news will spread in hushed tones. I think of how they will fuss around Matt, eyes full of pity, of how they will never understand what I have done. I think of how he will have to excuse me, talk of grief, and how they will say that six years of grief is excessive.

And I know that they are right.

I think of Molly’s pink sandwich box, of routine, of her tastes, her quirks. I think of Matt struggling to find clean uniform, to dress, to juggle his work and his Molly. I know that he will be late for work if he waits for her to be clapped into school from the playground.

My thoughts are confused, jumbled, whirling.

I can still hear her sobbing.

I hope that Matt keeps her from school today, just today. He will need to go in to see the Headmistress, or telephone her, or both. The teachers will have to be told what an evil mother I am, of how I have abandoned my daughter and run away to a foreign country with my only son. But I know that any words exchanged will be missing the purpose, the point, that they will never fully understand why. I know, I appreciate, that people will be quick to judge me. I would hate me too. But, still, leaving my Molly, leaving my beautiful girl is dissolving any remnants of my remaining heart.

I think of her.

And then, suddenly, I am missing her, too much.

My sobbing vibrates through my body; it causes me to snort snot from my nose. My sobbing causes tears to stream.

and my shoulders shudder.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

beyond control.

I am out of control.

I pull my large shawl tighter around my shoulders. I bring the two ends together, up to my face, again. I bring the smooth material onto my face, until it covers my eyes, my nose, my being.

I breathe into my shawl.

I wonder if my Lord is laughing at me.

She wakes me.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’

I forget; for a moment, I am unsure where I am.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’ she repeats.

I look at her trolley. I see tiny bottles in a drawer.

‘Two whiskies, please,’ I say.

‘Ice?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘A mixer?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Anything else?’

I look to Christopher, he is absorbing the film; I wonder if he is reading lips, if I should buy him a headset. He seems to be on another planet, not really with me today, an outline.

‘Do you want a coke?’ I ask him.

Christopher looks at me then shakes his head.

‘Nothing else,’ I turn, I tell her.

‘Sorry?’ She is confused.

‘Nothing else,’ I repeat, louder, almost a shout. She nods, takes the drinks from the metal drawer; she does not question me any further.

‘That’ll be five pounds.’ I hand her Matt’s money, as she pulls down the table clipped onto the chair in front and places the drinks before me.

The whisky burns my throat but at least I feel something.

I stare out through the oval window, watching, waiting.

I see the sea, the deep blue sea.

The seatbelt sign goes on.

within minutes the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal is heard.

‘Cabin crew, ten minutes till landing,’ he says but we all hear.

And then, the plane is descending, rocking, bowing, dipping, shaking, swaying.

And then, I see Malta.

I see my Malta.

The island looks so tiny. I look through the small oval window. I see white, grey, green, blue. The natural colours dance before my eyes, they swirl and twirl and blend.

And as the plane dips, the colours form into outlines, then buildings, looking as if they have been carved into rock, into a mountain that never was. A labyrinth of underground, on ground, overground secrets have formed and twisted into an island that breathes dust. An island surrounded in, protected by a rich and powerful blue. I know that there is so much more than the tourist eye can see.

Quickly, the plane bows to my country, the honeypot of the Mediterranean.

And then, the wheels hit tarmac.

Merba.

~welcome.

I am home.