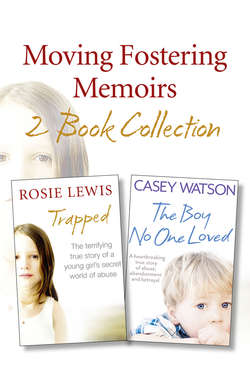

Читать книгу Moving Fostering Memoirs 2-Book Collection - Casey Watson, Casey Watson - Страница 16

Chapter 9

ОглавлениеBeing at home with Phoebe had me in a constant state of the jitters. All my senses were on high alert, ready to absorb the sudden high-pitched screams or defend myself against unannounced air-borne crockery. Besides lobbing dangerous objects, Phoebe had an unnerving habit of creeping up on me. I’d be in the kitchen washing up or bending to retrieve a tin from the food cupboard when a prickling sensation on the back of my neck signalled that I wasn’t alone; I would turn to find Phoebe standing there, watching me.

I decided it might be easier being out. Our trip to the park the previous day had passed by peacefully enough, barring a few stares and pavement dodgers, so I rose early and packed a picnic. It was such a lovely bright spring day that it felt wrong not to make the most of it and besides, I figured the time would pass a lot quicker if we were out keeping ourselves busy. As an added bonus, Emily had decided to take a break from revision for her mocks and join the rest of us, so it was with a feeling of optimism that we set off towards Dunham Massey, a Georgian house run by the National Trust.

It was a long drive but Phoebe was surprisingly calm throughout the journey, and so by the time we pulled into the stunning entrance to the grounds we were all relaxed and eager to explore the magnificent deer park before making a tour of the old house. In the idyllic setting Phoebe seemed to blossom, skipping and laughing as we ventured through a large wooded area and down to the lake. It was at times such as this when fostering felt like a genuinely rewarding, enjoyable experience. Besides the satisfaction that comes with building happy memories for a child under stress, I was able to enjoy visiting new places alongside them. Halfway through the morning a group of us gathered by Dunham’s Mill for an Easter egg hunt organised by the staff. Phoebe was beside herself with excitement and yet there was no arm flapping or strange limps as she walked over to collect her clues. From the confines of my mind a voice was whispering to me, trying to tell me something about the randomness of her behaviour, but for some reason I couldn’t quite turn the volume up enough to grasp what it was. Phoebe sat with Emily and Jamie, sucking on the end of her pencil with a look of utter concentration on her face, only distracted briefly by one of the stewards, whom she labelled a ‘fat bitch’. She scribbled away intermittently, and I was surprised to find that, although her writing was sprawled untidily across the page, it was definitely legible.

By lunchtime we were all ravenous, so I decided to treat us to some warm chips to go with our picnic sandwiches. The restaurant was located inside a converted stable with cosy seating areas built into each block, where horses had once slept. Large oak beams were a reminder of the building’s previous life, as well as the wrought-iron feeding troughs still fixed to the wall, now filled with geraniums and trailing ivy.

Jamie grabbed a tray and scanned the menu that was written on blackboards behind the counter. ‘Do you serve chips on their own?’ I asked the young girl by the till, closing my eyes and releasing a groan as Phoebe began retching behind me.

Emily and I exchanged glances. ‘It’s alright, Mum, I’ll take her outside and try to find a spare table.’

By the time I left the restaurant, with a tray with four bowls of chips balanced on my outstretched arms, Phoebe had worked herself up into a frenzy. ‘I WANT PORRIDGE!’ she screamed, stamping her feet. ‘Not chips or sandwiches or any disgusting stuff, just PORRIDGE!’

‘You can have porridge when we get home,’ I said soothingly, disguising my horror for Jamie and Emily’s benefit. I didn’t want to draw any more attention than we already had and the pair of them looked mortified. ‘For now, just try to nibble some chips, or even just a piece of bread.’

Two women planted their bags on a table a few feet away from the one Emily had claimed and gave us a cool inspection. They were well-dressed in trendy clothes, each with a patterned scarf arranged in evenly sized loops around her neck. I was accustomed to cupped whispers and double takes when I was with foster children, whether it was because of their bad behaviour, outlandish names or unusual physical appearance, but most people made a half-hearted effort to disguise their stares. But not this pair, with their flared nostrils and narrowed lips: they were looking at us as if we smelled bad.

I remembered the looks I got when I took three-year-old Alfie out. With patterns shaved into his number one crew cut, the centre of each eyebrow removed and a silver stud in one ear, we never failed to gain negative attention.

‘No, blwah.’ Phoebe doubled herself over, making a show of retching loudly. Although she had genuinely gagged in the past, I was beginning to suspect this current drama was an act.

There was a tensing in the posture of the two women as they each lowered an immaculate-looking toddler into a high chair, an indiscreet exchange of glances. I tried my best to ignore them, ushering the children to sit around our table. The two women drew out their own chairs and sat down, making sure they positioned themselves to get a good view. Their open-mouthed, unblinking expressions unnerved me but the more they stared, the less I felt like moving. I wasn’t going to be cowed into abandoning our table just to suit them. They continued to size us up as I finally managed to persuade Phoebe to take a seat next to me.

As if their smug superiority needed any more fuelling, Phoebe suddenly raised the stakes, angrily sweeping our bowls of chips from the table, then throwing her head back, screeching with alarming force.

One of the women winced at the sound, as if her eardrums had been physically twanged. Then, leaning in, the pair huddled together and spoke in loud whispers. A light wind masked their voices so I only caught the tail end of the sentence. ‘… people really need parenting classes … allowed to breed like that,’ said one. Her friend nodded in wholehearted agreement, shooting me a sharp look.

I drew a deliberately long breath, wanting to correct them but resisting the urge. My own pride shouldn’t come into it, I told myself. Phoebe had as much right to be there as they did, I thought, surprising myself with the strength of protectiveness I felt towards her. ‘I’m sorry for the noise,’ I called across to them, although it was clear that they weren’t interested in pleasantries from ‘someone like me’. What I really wanted to say was that they were in danger of indigestion with all the air they were sucking in through their gaping mouths.

‘That’s quite alright,’ one woman said airily, with the patronising air of an accomplished mother confronted with apparent Slummy Mummy. In spite of the politeness in her tone, I knew there was no genuine warmth there. I could have told them then that I wasn’t Phoebe’s mother, but suddenly I had no urge to do so. It was perverse, I suppose, but withholding information from them gave me a sense of satisfaction – I didn’t care, let them judge me.

In that moment I could understand why people sometimes behaved in outlandish ways as a form of protest, perhaps by having offensive tattoos or pierced body parts. It was a strangely pleasurable power, being able to irritate the snooty women simply by being there.

Later in the afternoon, as we were queuing for an ice cream, we encountered the same two women: they joined the queue just behind us, their toddlers standing patiently by their sides, still looking remarkably spotless.

‘Can I just have some chocolate, Rosie?’ Phoebe asked. ‘I don’t like ice cream, blwah, yuck!’

There was a quizzical cast to their eyes as they ran over our hotchpotch group, finally settling on Phoebe. One of the women opened her mouth to say something but perhaps she noticed a reserve in my stance because she faltered and closed it again.

‘Yes, OK, honey,’ I said, still aware of the woman’s internal battle. She was probably unsure as to whether to risk having a conversation with a mother so disgraceful as me. A moment later and curiosity had evidently got the better of her.

‘So, do your children not call you “Mummy” then?’ she asked, her face contorting like she was chewing a wasp; she couldn’t disguise her disapproval.

‘I’m a foster carer so, no, she doesn’t call me Mum.’

As soon as I uttered the word ‘foster’ they both noticeably thawed. One of them clapped her hands to her face: ‘Oh, I could never do that! Could you, Celia?’

I cringed, wondering how on earth Phoebe must feel being spoken about as if she was a hot potato that no one wanted to be left holding.

‘Oh no, I just couldn’t!’ Celia cried. ‘I’d get too attached.’

Somehow I doubted that to be true. The pair of them hunkered round to include me and suddenly I was part of a triangle. Shifting uneasily, I turned back to the children, trying not to notice that I was being rewarded me with benevolent, apologetic smiles.