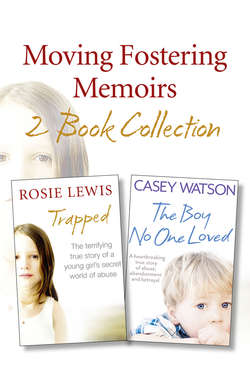

Читать книгу Moving Fostering Memoirs 2-Book Collection - Casey Watson, Casey Watson - Страница 18

Chapter 11

ОглавлениеPhoebe was withdrawn when I drove her home from hospital later that day. She sat listlessly in the back of the car, her head resting against the interior of the door. Her face was still pale, although now I realised this was probably more down to shock than anaemia. The emergency paediatrician had kindly reassured me that blood loss from the deep cut she had scored into her arm was unlikely to have been more than a few dessertspoons, despite the scene of massacre in her bedroom. She’d been lucky, though: if she’d hit on an artery it could have been a different story. I shuddered at the thought.

‘You must be exhausted, honey,’ I said, glancing at her reflection in the rear-view mirror. It was the first time I had actually willed her to mimic me. She didn’t, hardly reacting at all. Her blue eyes stared glassily ahead. I wasn’t even going to attempt to discuss what she’d done to herself, not yet. She needed time to recover physically before I drained her further, I felt. But how long to leave it? I wondered. And would she even remember doing it by the time we spoke?

I winced as I cast my mind back to the early morning, ambulance men negotiating their way through the decapitated teddies to reach the injured patient. Phoebe lay in a hysterical heap on the floor, spurred into life by the sight of strangers in her room. I watched as the paramedics knelt beside her, trying to examine her wounds, her fending them off with wild kicks and ferocious screeches. All I felt then was relief; at least she was conscious.

The police had interviewed me while Phoebe’s injury was glued together by a doctor. It was only a formality and yet I couldn’t help but feel responsible for the whole episode. Upon interrogation from nursing staff, Phoebe had admitted to stealing a pair of scissors from the kitchen while I was washing up. Children in foster care often become experts in subterfuge and although I never suspected that she was likely to self-harm at such a tender age, I felt I should have been more alert to the possibility.

Sneaking the scissors up to her room, she had stowed them under her pillow and slept with them there all night. That revelation in itself was shocking enough but the realisation that an eight-year-old girl was disturbed enough to gouge a hole in her arm on waking rocked me to the core.

I realised it would be difficult ever to relax with Phoebe in the house; I would have to stay continually on guard. Once indoors I planted Phoebe in front of the television. Absorbed deep in a world of her own, she sank into a beanbag and stared blankly at the screen.

I was about to call my mother and arrange to collect Emily and Jamie from her house when the handset vibrated in my hand: it was Lenke. I walked into the garden where we could talk in private, watching a listless Phoebe through the glass of the patio doors.

‘How is she doing now?’

Hearing the social worker’s reproving tone, I instantly bristled. ‘She’s a bit withdrawn but physically there’s no long-term damage, thank goodness.’

‘Hmmm. Have you reviewed your safeguarding procedures? Her parents are furious that this happened in the foster home, as you can imagine. They’ll try and use this to discredit the local authority, of course.’

‘It was an ordinary pair of household scissors, Lenke. If I’d had any idea at all that Phoebe was vulnerable to self-harm I would never have allowed her access to them. As it is I’ve had to hide the washing up liquid and soaps, all the toiletries, even toothpaste – she devours it all.’

There was a moment’s hesitation. A cough. It was then that the realisation dawned on me.

‘You knew,’ I said slowly, feeling a prickle of heat. ‘She’s done this sort of thing before, hasn’t she?’

‘Well,’ another pause, then, ‘the school mentioned some risky behaviour in the reports but we’ve only just had time to read through them.’ She offered this information in a casual tone, as if it were an amusing anecdote that might set me off chuckling. I wondered why the school hadn’t mentioned anything to me, then I realised what her teacher must have meant when she referred to ‘a few frights along the way’.

‘You knew she was a self-harmer? Why wasn’t I told?’

‘Like I said, we’re still sifting through the information but we need to make sure that nothing like this happens again.’

‘How do you suggest I do that – handcuff her to the bed?’ Admittedly it wasn’t the subtlest of replies but I was in no mood for diplomacy.

‘There’s no need to take that attitude.’

‘I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said that but I’m afraid there’s no way I can guarantee her safety, Lenke. Her problems are too severe. As it is I can’t take my eyes off her in the day, not for a minute. How am I supposed to keep her safe during the night – lock her in a padded room? And don’t you think it’s time to bring CAMHS in now? Something has to be very wrong for her to feel the need …’

Lenke interrupted me. ‘Phoebe is already under the consultant for the autism.’

I gripped a handful of hair and pulled it back from my forehead as I listened to her, pacing the patio with impatience. ‘Self-injury is common in sufferers and the hospital have no concerns about her home life. I’ve discussed this with Mr Steadman and he said that her symptoms were bound to be more troublesome during times of change or stress. He says that is all the more reason for the foster carer to be extra vigilant.’

Sighing, I stopped mid-pace and leaned my head against the glass, shielding sunlight from my eyes to get a clear view of the living room: the beanbag was empty. With a sinking feeling, I yanked the door open in one swift motion, hurrying from room to room.

‘So anyway, since we’ve discussed Phoebe on the phone, I’ll log this call as one of my visits, yes?’

‘Fine, yes,’ I agreed quickly, saying a hurried goodbye before I realised what she was actually asking. Where on earth was Phoebe? Charging up the stairs, I finally found her standing stock-still in the middle of her room, a guilty grin spread across her face.

‘What have you been doing up here, Phoebe?’

‘What have you been doing up here, Phoebe?’

I sighed, not realising that in less than 10 minutes I would find out why she was looking shamefaced.

Even in the context of the last, difficult week, when I went downstairs and opened the post the kicking, smearing, mimicking, even the self-harming, paled into insignificance next to the contents of one of the letters. The envelope was hand-written and so, as I knew it was unlikely to be a bill or circular, it drew my attention immediately.

I tore it open, immediately registering the signatures at the bottom of the page: Will and Carolyn x.

It was Tess and Harry’s new parents, who had recently adopted the two toddlers I had fostered. A slow nausea rose in my throat as the words, ‘very sorry’, ‘clean break’ and, ‘really feel it’s for the best’ jumped out at me. Confused, I scanned the letter over and over again, trying to take in its contents. Slowly the message surfaced – they had come to the ‘difficult’ decision that it was best not to allow me to stay in touch with the children.

Will and Carolyn had been advised not to cut ties with me when they adopted the siblings since children can suffer lifelong depression if early attachments are severed. Scrutinising the letter again, I began to absorb their apologetic reasoning. It seemed Tess and Harry had spent their first few weeks searching for me – in cupboards, behind doors – unable to take in their loss. Now, five weeks later, they finally seemed to accept their circumstances and their new parents were concerned that seeing me would set them back and start their grieving process all over again.

Sinking into the sofa, I gripped the letter in my hand and held it to my chest. It was horrible to think that the children I had cherished for nearly three years had been searching for me. A wire of guilt passed through me at the thought of them feeling so abandoned. In turmoil, I tried to absorb the prospect of never seeing the siblings again.

Sensing someone near, I looked up and noticed Phoebe hovering in the doorway. She was staring at me strangely and I assumed she was confused by the look on my face. Slowly, she drifted into the room and sat beside me on the sofa, close enough for me to feel the warmth from her thin body. Was she seeking comfort after the tribulations of this morning or had she somehow intuited my despairing mood? Whatever the reason, I was touched and grateful for her gentleness. Instinctively I responded, wrapping my arm around her shoulder.

It was then that she slipped her hand into my own, tilting her face up to smile at me. The grotesqueness of her twisted features hit me first, before I registered the slippery feel of her palms against my own and the dank, acrid smell rising from my lap.

Phoebe had soiled in her own hand, catching me completely unawares.

By dinnertime my nerves were so shredded that when Phoebe made a grab for Jamie’s fork I felt my hackles rise. ‘Put that down,’ I snapped. ‘You only need a spoon for porridge.’

‘Fuck off!’ she spat.

I raised my finger and, waggling it in front of her face, I burst out: ‘Don’t talk like that in this house,’ oscillating emotions making my voice quiver. It wasn’t the swearing that unsettled me so much as the look in her eyes. Not simple defiance, something far more disturbing: pure, unequivocal hate. ‘Now, go to your room and stay there. Do you hear me?’

Her gaze remained bold and challenging but I was relieved to see that she wasn’t going to put up a fight. She slipped quietly from her chair and left the room.