Читать книгу Moonrise - Cassandra King - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSUMMER FOLKS

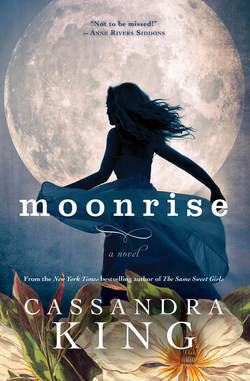

It’d make more sense for me to start at Moonrise and work my way around to Laurel Cottage, but I don’t. Never have. Old habits die hard, and I’d druther end up at Moonrise. Completes the circle, I reckon. Another of my foolish notions, Momma would say. She only had Moonrise, though, not the slew of houses I have. Sometimes I wonder what she’d think about me having my own property management company, with so much responsibility. Momma wasn’t what you’d call ambitious. She was content with Moonrise, content to have me end up a housekeeper like her. It was her lot in life, something a good Christian woman like her would never question.

I know that Momma’d understand why I clean the houses at Looking Glass Lake myself, even though I’ve turned the other places over to my crew. Boss lady does the lake houses, I hear the girls telling one another. Most of them don’t speak much English, but they’re good girls, and good workers. Truth is, I do only three of the lake houses—Laurel Cottage, Moonrise, and the Varners’ cabin—and all have plaques out front saying they’re on the National Historic Register, which makes me proud.

The fourth of my lake houses, Kit Rutherford’s, I’ve started sending Carlita to clean. Thank the Lord that Carlita pleased Kit ’cause I never could. Duff still works for her, though, which gets my goat. She’s snippy with my helpers yet lets him get by with anything: sloppy work, showing up half crocked, borrowing money, whatever. I tease him, saying it’s those tight jeans and wide shoulders of his. I let Duff think he’s hot stuff, but in truth, I don’t worry about Kit flirting with my fellow. That woman likes her men rich, with one foot in the grave and the other on a banana peel. After Kit’s latest husband, Al Rutherford, kicked the bucket, she contested his will, and took his kids to court. Even though Al had left her well-off, she wanted more. No one expected the judge to take the Rutherford house away from those poor kids and give it to Kit, but that’s exactly what happened. Next thing you know, she sent bulldozers in to tear up the yard with its beautiful old gardens so she could fix her some new ones. Folks in town are still wagging their tongues about that!

If I’m gonna finish today before everybody gets back from their outing, I better shake a leg. I don’t like cleaning houses while the owners are home, getting in my way, talking to me, and normally it’s not a problem. This summer, though, everything is different. Maybe it’s because my folks have been here about a week and haven’t settled into all the changes that’s taken place since last year. And there’s been plenty of changes besides that ugly house and torn-up yard of Kit’s. Noel and Tansy arrived fussing and snipping at each other, worse than ever. But most of all, Emmet showed up with a new wife, then Linc in a walker. (Wish he’d been the one with a new wife.) Linc’s doing much better than I expected, though, good enough that his friends were able to take him out sightseeing today.

Even though I hope to finish all three places before sundown, I can’t hurry through Laurel Cottage. Too many antiques and whatnots, which I take my time dusting and cleaning. Every room in the house—even the bathrooms—has pictures hanging on the walls, and Oriental rugs on the floors so old they’re about to fall apart. I’ve never counted, but I bet those hutches in their dining room hold three hundred pieces of china each. One time I asked Tansy if they had that many dishes in their Atlanta apartments, and she said, “Honey, you wouldn’t believe it.” She’s right; I probably wouldn’t.

It don’t take me as long to finish Laurel Cottage today because Noel keeps everything nice and clean when he’s here. Funny, him being more persnickety about neatness than Tansy is. Laurel Cottage originally belonged to Noel’s family, though Mr. Clements left it to him and Tansy both. Momma didn’t hold with gossip much, but she did tell me all about that situation. She said Mr. Clements didn’t have to do such a thing, since he only courted Tansy’s mama instead of marrying her, but that was the kind of man he was. Good-hearted and decent, despite him being rich as a lord. Mr. Clements treated Tansy like the daughter he never had. You’d think Noel would resent sharing his house with somebody who’s not blood kin, but no. Momma always said that Noel was every bit as fine a man as his daddy. “Fine” has a different meaning these days, and Noel Clements is sure that, too.

Noel and Tansy have the most peculiar relationship of anybody I know, and that’s saying a lot among the summer people. They live together, but not really. They date other people, or each other, and it don’t seem to matter to them which. Both have been married to other folks, and neither came to Highlands much during those days. Well, Noel couldn’t, I reckon, since he married a Frenchwoman and spent a lot of time overseas. Tansy’s tied the knot twice, both times to men old enough to be her daddy. Seems like one—or both—of her husbands died recently. One of them was funny, I recall—“funny” like in homo, and Noel teases her about it. Not about the guy being homo—Noel’s not like that—but about Tansy marrying him and not knowing. Peculiar as they are, though, Tansy and Noel are sure entertaining to be around.

Laurel Cottage is the prettiest of all the houses I manage, even Moonrise. Moonrise is more famous, but it’s creepy to me. Plus Moonrise is cold all the time, even in the summer. Laurel Cottage is more what a house in the mountains oughta be, but in a good way, not like those gussied-up ones with pictures of bears on everything, even furniture. Summer folks actually think bears are cute. You won’t see any bear stuff at Laurel Cottage, cute or otherwise. It’s been written up in a lot of decorating magazines, which Tansy frames and hangs on the walls.

Standing at the kitchen sink of Laurel Cottage, I arrange a bunch of white dahlias in a heavy antique vase. It’s a personal touch of mine, fixing flowers from the owners’ gardens after I clean their houses. I’m halfway up the stairs with the vase in my hands when my cell phone rings. Probably just Duff, aggravating thing. He knows I’m at work, and he’s supposed to be.

I’ve just put the vase on Tansy’s dresser when my phone goes off again. I pull it out of my pocket, and sure enough, it’s Duff. “Hey. Whatcha doing?” he says.

“I’m at the Old Edwards Spa, Duff, getting my toenails done while I wait for the hundred-dollar massage,” I snap. “What’d you think?” With an exasperated sigh, I add, “What’d you call for? I don’t have time for your foolishness today.”

“Just to remind you about us singing at the prayer meeting tonight,” Duff says.

“You think I’ve gone senile?” I ask him. “We’ve been singing at every prayer meeting for a year now. Though all your churchgoing ain’t done you a bit of good, far as I can tell. Every night you’re not in church, you’re at the juke joint.” Then, hearing him sucking on a cigarette, I sigh again. “And you’re smoking, ain’t you?”

He tries to deny it but starts coughing, bad. “Naw. I quit, like I told you,” the liar says.

“I’m going now,” I tell him meanly. “I’m not listening to no more of your lies. After that doctor said you might lose your voice, I thought you might straighten yourself out.”

I slam the little phone shut, cussing. But before I can get it tucked back into my jeans, it’s ringing again. This time it’s Helen.

“Willa?” she says, and I reply, “Yep, it’s me.” Then I worry that they’re on their way home, and I haven’t even made it to Moonrise yet. But they’re still touring the Biltmore Estate, she tells me. “Listen,” she says, “I called to see if you’d do me a favor when you get to the house.” No surprise, she wants me to make sure the oven’s off. They’d only been here a day or so when Helen smelled gas and had the gas company come out in a hurry. She’d turned the oven on, the guy told her, without making sure the pilot light was lit. Helen had a fit, swearing she did no such thing—she hadn’t even been in the kitchen. It was pretty obvious that no one believed her.

I tell Helen not to worry, I’ll check it out. “I didn’t touch the oven this morning,” she says with a nervous laugh, “but still. And Willa? I’d appreciate you not saying anything about my call, okay? Can’t have everyone thinking I’m scatterbrained.”

Another little laugh, and she’s gone. We hang up, and I start back downstairs, shaking my head. Lord, that poor woman! Bless her heart. Last month, when she called to say she and Emmet had decided to spend the summer in Highlands, she asked if I could get the house comfortable for them. I wanted to tell her that I was the property manager, not a miracle worker. If there’s anything comfortable about that old-timey place, I’ve yet to find it. Turns out she meant having it wired for the Internet and stuff, which was at least doable. She and Emmet couldn’t stay, she said, unless an office could be fixed up for both of them, since they had a lot of work to do this summer. A working holiday, she’d called it, which tickled me.

Helen seems so earnest and is trying so hard to be liked, but I have my doubts. I like her fine myself, but she’s gonna have a hard time fitting in here. I’ve been knowing these folks all my life, and they’re not an easy bunch. I love ’em to death, and they’re good to me, but they’re strange. Linc’s the best of them, but he’s a college professor, and half the time he uses big words I don’t understand. That Yankee wife of his thinks she’s better than everybody else, especially me. I pure-tee cannot stand her. Noel and Tansy couldn’t be nicer to me, but they talk crazy and act the fool. Kit Rutherford is a snot, though she tries to act like she’s sweet as pie. Then there’s Emmet. Momma used to say that Rosalyn Harmon was the only woman who could be married to Emmet Justice because she knew how to handle him. I find him pretty scary myself. Not mean scary, but scary the other way. He stares at you with those clear-colored eyes of his, then fires questions your way like he’s interviewing you on his TV show. It makes me nervous, and I avoid him as much as I can. All I can say is, poor Helen’s got her work cut out for her.

I got another worry besides Helen, though. Driving down the road to the Varners’, I wonder what I’ve got myself into by promising to help out with Linc. I start next week, after that wife of his gets on her broomstick and flies back to Alabama. I love Linc to pieces but have problems with Myna. I can’t figure out what Linc ever saw in her, even if she is a big-shot writer. All those years he’d been a bachelor, then Myna comes from New York City to speak at Bama, and next thing you know, she’s got her hooks into him. And her not even pretty! Everything about her is sharp—elbows, collarbone, chin, eyes, and tongue.

Only good thing is, Myna don’t like Highlands, so she won’t be around much. Never is. She goes someplace—Maine, seems like—where her people have a summer home. She’s always telling Linc how his house don’t measure up to her family’s “compound.” If I was him, I’d tell her to keep her skinny ass up there, then. Although the Varner house is an authentic, old-timey log cabin, and sits right on the edge of the lake, Myna complains that it’s dark, cramped, and smells like a fireplace. Shoot, that’s what I like about it! Actually, Linc’s cabin is a lot like the old homeplace I was raised in, which belongs to me now. Both of them have the same pointy tin roof, blackened chimneys on the sides, and laurel rail porches. And each has chinked log walls and fireplaces made of rocks from the Cullasaja River. Only difference is, mine is the one without the brass plaque.

Linc hadn’t been to Highlands since his stroke, but the cabin has handicapped rails and stuff now. Myna sent me a list of how she wanted things done, but not many of her orders were carried out. One weekend Noel met me there and changed everything on her list. Just between us, he told me with a wink, and brought in his own workmen. He was damned determined Linc’d be comfortable here, he told me. Noel won’t say nothing bad about Myna—not to me, anyway—but it’s obvious how him and the others feel about her. It tickles me the way they all pretend to like one another, regardless. Summer folks are bad about that, I’ve noticed.

I brought some of Tansy’s dahlias to Linc’s house, so I go outside to get fillers, maybe a little buddleia and oxeye daisies. Summer people love their flower gardens, and all over Highlands are the prettiest, showiest ones you’ve ever seen, with statues and waterfalls and goldfish ponds. Odd thing is, men and women alike work in their flower beds. Duff can’t believe that the men belong to garden clubs just like ladies do, but he thinks all summer people are weird. And most of the locals feel the same way.

I gather a handful of buddleia from Linc’s butterfly garden, but gotta get the sprinklers going next—Linc’s not happy with his garden, and neither is Tansy with hers; least they know I’ve done the best I can. Western North Carolina is in such a bad drought that the lakes are all down, and some of the waterfalls nothing but trickles. The governor’s been asking everybody to pray for rain. The Lord’s liable to tell us we can’t keep on using up everything He gave us, then holding out our hands for more.

Linc’s yards are different from everybody else’s. He’s one of those professors who studies butterflies and teaches his students about them, so his garden’s like a science lab. Used to, if you needed to find Linc, look in the yard. Day and night, he’d be squatting out there taking notes and pictures of caterpillars and cocoons. Wonder how much he’ll be able to get around it now, with him in that walker. Part of my job will be taking him for walks to build up his legs, then he can start using a cane instead. Most of our strolls will be through the butterfly garden. I ’spect it’s going to be tough, seeing him wanting to squat down and study things, and not being able to. Maybe taking notes is something else I can do for him.

Driving down the dirt road that circles Looking Glass Lake, I catch myself humming a little song. I can’t help myself, being excited about the arrival of summer. Winters here are so gray and dreary. Seems like spring will never get here, then it’s gone as quickly as a cheating boyfriend. Only excitement we have in these parts is when the summer folks roll in. Everything, and everybody, picks up then. Highlands is a small town, just a few blocks of downtown storefronts, but you’d never know it come summer. The newspaper wrote that the town swells with tourists, and that’s what it feels like. Swollen, like a big ripe persimmon about to burst open. Excitement fills the air the first week of June, and it don’t leave till the cold winds of winter blow back in.

The road leading up to Moonrise isn’t much wider than a pathway, and I pray I won’t meet another vehicle. If so, nothing to do but back out. The road winds through a laurel and rhododendron forest where pink-and-white blooms hang so thick and heavy overhead that you can’t see the sky. Not seeing is good at certain spots, where the road hugs the side of the mountain. Looking down is not for the faint of heart. The drop-off’s not near as bad as some, but it’s still plenty scary. Sure hope Emmet’s warned Helen about driving on mountain roads, especially after what happened to Rosalyn. Helen told me she’d never spent any time in the mountains, nor been around anything higher than a sand dune.

Suddenly the rhododendrons clear out, and there’s Moonrise. Big old ugly thing that it is, it never fails to take my breath away. The way it looms out of the clearing is a surprise, with its rooflines of different heights, and the round turret like a fairy castle. The walls are made of local river rocks, but they’re about covered with ivy. Takes all me and my crew can do to keep it cut back so it don’t cover the windows—why it’s so dark inside. Everything here looks good, though, long as you stay in front. The back’s another story. I kept telling Emmet how bad Rosalyn’s gardens had got, but he won’t let my crew, or nobody else, work back there. He don’t want them moon gardens here, not ever again. Let them go to rack and ruin, he said, and they up and obliged him.

I brought more of Tansy’s dahlias here, too, not wanting to wade through the overgrown gardens looking for blooms. I leave the front door open to catch the breeze blowing up from the lake, which is sharp and pine scented. No matter how often I air it out, the inside of the house is always musty and damp. And cold as a well digger’s ass.

Even though it’s broad daylight, I go around turning on lamps. My work boots sound like a mule clopping on the slate floor of the entrance hall, but I don’t mind. It’s way too quiet here. Always is. Turning on the lamps don’t help much because they either have painted globes or dark, fringed shades. Not a plain, ordinary lamp on the premises, but then, it’s not an ordinary house. After Momma got too sick to work here anymore, I took over. That’s when Rosalyn showed me how to take care of everything, way more information than I gave a fig about. When the house was on garden tours and things like that, Rosalyn was the guide. She insisted I tag along until I learned the history of the house.

When I asked Rosalyn how come the furnishings were so fancy, she told me they were Victorian, as though that explained it. All I know is, the Victorians couldn’t leave anything alone. Every dang thing in the house is gussied up with fringe, ribbons, scrolls, scallops, embroidery, flowers, feathers, or beads. Worse of all is the furniture. The tables, chests, and sideboards are as big and heavy as coffins, with deep carving you can’t half dust. The fabric they used isn’t easy to clean like the kind we have nowadays, either. Oh, no—nothing would do them but velvet and satin and linen and lace. If I was Helen, I’d yank down all these brocade curtains and let in some light! Then I’d get someone to haul off every last piece of the furniture, even if it did belong to Rosalyn’s family.

I head down the hallway to the kitchen, carrying my basket. The stove’s cold as a stone, with no smell of gas, but Helen was right to double-check. As old as that thing is, it could spring a leak, I reckon.

I notice that Helen’s using the glassed-in porch as their sitting room now. The TV, something most summer folks don’t even have, is in the back parlor. Rosalyn had to put one in for Emmet, who never misses the news. Unlike most kids, Annie wasn’t bad about watching TV, but she wasn’t here much. Always off at some horse-riding camp. Now she’s grown into a young woman I barely know. She’s nice enough, but kind of a hippie chick. I wonder if she’ll visit here, get to know Helen. Even before her mama died, Annie and her daddy didn’t get along so hot. He was always fussing about her dropping out of college, and not doing anything with her life. Last I heard, she’s living in Boone and working on a horse farm.

I put my basket of homegrown tomatoes on the counter, and some fresh eggs in the fridge. I felt bad for Helen when she first saw the kitchen, and her a cook on a TV show. She tried to play like everything here was “quaint” and “charming,” but didn’t fool me none. I knew good and well that Emmet hadn’t told her how old-timey it was, or how Rosalyn wouldn’t change anything. Helen told me how she’d be trying out recipes for her new cooking show this fall, and how she’s writing a cookbook to go along with it. She sure won’t get much cooking done unless she fixes up this god-awful kitchen. Rosalyn didn’t cook because they either went out to eat, or had stuff catered from town. It’s obvious that Helen’s gonna be a lot different, but especially in the kitchen.

Upstairs, I lay the wood in the marble fireplace of the master suite, then turn back the covers on the bed. The mahogany half canopy is draped in heavy old lace, and looks like it was made for the bride of Dracula. So does every other dark, ugly thing in here, including the wallpaper. Poor Helen was going to use another room until she saw this was the only one with a shower. She had a hard enough time talking Emmet into coming here, she told me with a sigh, to make him go down the hall to bathe. So she was stuck with it. After placing a vase of yellow dahlias on her night table—trying to brighten things up—I skedaddle out of there.

Coming down the shadowy hallway, just before I get to the landing, it happens again. I’ve never told nobody, but there’s a reason this house spooks me. Even before Rosalyn died, I had some strange experiences here. I’d be by myself, maybe downstairs in the kitchen, and I’d hear something upstairs plain as day, clomping around. For the longest time I didn’t think nothing about it, so I’d go barreling up the staircase like a fool, thinking a squirrel or coon had gotten in. I never found a thing, not even in the attic. What was more peculiar, the noises didn’t happen for a while, and enough time went by that I forgot about them. I’d come and go without looking over my shoulder for shadows, or jumping at the least little sound from dark, empty rooms. That changed last year, after Rosalyn died. Her funeral was held at a big fancy church in Atlanta, but the next day, the family and her friends came to Moonrise for a smaller service. They wanted to bury her ashes in the garden she’d loved. I’d only been to burials in the cemetery, not a person’s backyard. But I was raised to pay my respects to the dead, so I went.

The service turned out to be real nice instead of weird like I expected. They didn’t have a preacher, but Linc read a passage from the Bible and a pretty poem. Each of them said something nice about Rosalyn, then threw a handful of her ashes into the hole Noel had dug for that purpose. It’s way in the back of the gardens, beneath a magnolia that Rosalyn planted. When everybody finished, Noel refilled the hole, then put some rocks on the mound so it wouldn’t look so raw. Afterward, Emmet had a catered supper for everybody. I didn’t stay for that but came back the next day to straighten up. I was wiping the kitchen counters when I heard it again, upstairs in one of the empty rooms. Thump, thump, thump. That did it. I just threw down my dishrag and hightailed it out of there. And didn’t go back for several days, either.

Since then, there was only one other time I thought I heard the haints, and that was the day I first met Helen. It was over a week ago now, the official beginning of the summer season. I’d been on the phone with Helen on and off all day, tracking her trip from south Florida to Highlands. She and Emmet were driving separately so they’d both have their cars up here, and Helen had a couple hours’ head start. She didn’t know Emmet’d asked me to be at Moonrise when she got here. A house that old had too many quirks for anybody to figure out on her own, he said, especially after such a long trip. So when Helen called to say she’d cleared Atlanta, I headed over here. No cleaning since I’d done so already, but I brought her a welcome basket and some zinnias from my yard.

As I did earlier today, I’d laid a fire in the master bedroom and started down the hall when I heard a noise. Since I hadn’t heard anything strange here since the day after Rosalyn’s service, my knees went weak and my breath caught in my throat. I stood just short of the stair landing while a shiver ran up and down my spine. Oh, great, I thought. The new wife will be here soon, and who shows up to welcome her but those dad-blamed ghosts?

That’s when I realized the noise was coming from outside the house, not inside. From where I stood on the landing, I could bend down and see beneath the stained-glass inset over the front door. And when I did, I felt like a pure-tee fool. A car was parked out front, behind my truck, and what I’d heard was the slamming of car doors. It was a little gray Honda, and a woman stood beside it, peering all around. She must’ve made that racket getting something out of the trunk. Even though it was a tad earlier than I expected her, the new mistress of the house had arrived.

I remember how I watched her curiously, glad to have a chance before opening the front door and meeting her eyeball-to-eyeball on the steps. It turned out to be a stroke of luck, because it gave me time to put on my best poker face. One thing for sure: Helen wasn’t anything like I expected. Despite Kit and Tansy’s gossiping, I expected her to be more like Rosalyn. I couldn’t have been more wrong. At my first sight of Helen Honeycutt, I knew she was as different from the last lady of the house as any two women could be.

For one thing, she looked almost like a teenager standing there, the wind from the lake blowing hard enough to flatten her clothes against her, toss her hair every which way. Not many women could wear their hair that way, cut short and choppy with streaks of blond shot through it, but it suited her. She had a dark tan and a really good figure, like she exercised a lot. I expected her to be pretty and she was, but in a whole different way from Rosalyn. Rosalyn held herself like a queen, and turned heads wherever she went. I figured Helen turned a few heads, too, but for different reasons.

When people don’t know they’re being watched, they act more like themselves. That afternoon, Helen stopped just before she got to the stone steps leading up to the front door, and I got a better look at her. In spite of her sassy swing, she looked so anxious that I pitied her. Her sunglasses were pushed to the top of her head, and she was staring at the house with real curiosity. By the way her face lit up, I figured she was thinking, Good Lord, what a mansion. If she’d had any idea what she was getting herself into, though, she should’ve been thinking, Oh, shit. Get me out of here!