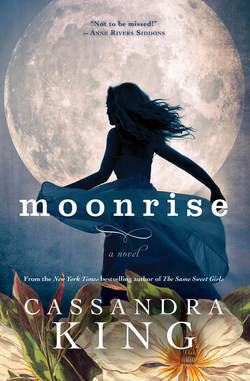

Читать книгу Moonrise - Cassandra King - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMOON GARDENS

Isit up with a start, my heart pounding. A noise like the scraping of a chair against the wooden floor wakes me, and for a brief moment, I have no idea where I am. The fire has died out, and a melancholy whiff of woodsmoke lingers in the cool air. Woodsmoke and something else, like the pungent aroma of sage. Pushing aside the crocheted coverlet, I swing my legs over the side of the bed, a bed so high that my feet barely touch the floor. I wait for a minute and listen for the noise again, but the room is quiet and still. The only sound is the soft snoring of my husband, who always sleeps like the dead. His back is turned my way, and I watch the gentle rise and fall of his bare shoulders. He is not one to be disturbed by things that go bump in the night.

I slip out of bed and stumble through the darkness toward the tall arches of windows just beyond the fireplace. Not once since we’ve been here have I closed the heavy brocade curtains, nor do I intend to. The lace panels provide just enough privacy for me to walk around in my nightgown, or wrapped in a towel after my bath. Tonight, however, I want light more than privacy, so I push the lace panels open. Like everything else in this place, the lace is antique, beautiful but fragile, liable to come apart in my hands if I’m not careful with it.

With the windows uncovered, the bedroom is bathed in moonlight, and I breathe a sigh of relief. Hugging my bare arms against the cold, I glance toward the bed to see if the moon, or the movement of the curtains, disturbed Emmet. Oblivious, he sleeps on, and I turn back to the window. Every night that we’ve been here, I’ve had disturbing dreams, or been awakened by strange noises. Even the wind rustling through the treetops sounds like someone calling my name.

It’s different in the daylight. I don’t jump at shadows, or imagine ghostly voices whispering my name. A couple of nights ago, I’d worked so late in my makeshift office that Emmet came downstairs to check on me. I lost track of time, I’d told him, and he had leaned against the doorframe, smiling an indulgent smile. Our eyes locked, and Emmet lingered. Come to bed, sweetheart, he’d said finally, his voice husky. When I muttered that I still had lots of work to do, he frowned. He wasn’t used to me turning away from him, or averting my eyes to avoid his gaze. Eventually he shrugged his shoulders and went upstairs alone. Because he’d think I was crazy, that he’d made a terrible mistake marrying me, I didn’t tell him the truth: I have to wear myself out before I can go to bed. It’s the only hope I have of sleeping.

The problem is, this is not my house, and won’t ever be. Everything here, including Emmet, belonged to another woman before I came along. Foolishly, naively, I thought that wouldn’t matter. I wanted so desperately to be welcomed and embraced that I believed I could make it happen. Wouldn’t it be obvious that I not only loved Emmet but also everything else: this old house with its ruined gardens, the gently lapping lake below, the cloud-shrouded mountains surrounding us? I’d expected to be loved in return, and to be entrusted with their care. What I didn’t expect was to remain apart, separated by a barrier of mistrust and suspicion. Instead I’m the outsider, the one who doesn’t belong. And it’s making me a bit crazy, especially at night, in this room. Her room. At times I even imagine she’s the one who calls my name.

With a sigh, I lean into the window frame and stare down at the shadowy gardens below. They were once magnificent, I’ve been told. In their glory days, the gardens were known far and wide for their unique beauty. Pebbled walkways formed intricate paths through flowering beds, around fountains and statuary, beside koifilled ponds before tapering off to terraces extending halfway down the mountain. Now the pathways are overgrown and indistinguishable from the weed-choked flower beds. Neglected, the koi have died, and the fountains dried up. Since the untimely death of Emmet’s first wife, the once-glorious and much-heralded gardens tended for generations by her family have gone to ruin.

In stark contrast, the grounds in front of the house remain intact, the lawns manicured, the formal beds and topiary pruned to perfection. You can approach the house from the lake without even being aware of the ruined gardens in back. I certainly wasn’t, when I got here at the beginning of summer. Coming up the long driveway through a leafy tunnel of rhododendron, you emerge to find the house suddenly looming in front of you. Set in the midst of wide lawns and stately hemlocks, the stone house with its ivy-clad walls appears to have sprung from the mountainside. It’s a sight that once drew flocks of tourists to this area.

I had heard little of the history of Moonrise before I came here. Maybe I wouldn’t have been so eager to come if I’d known more, though that’s pretty unlikely. I’ve always been overly imaginative, and way too romantic for my own good. It’s a part of my nature that has caused me not just a lot of disenchantment but also considerable grief. From the first moment I heard about Moonrise it became an obsession. Emmet grew alarmed when he saw my obsession taking hold, and who could blame him? After all, I was asking him to take me to a place he didn’t want to go, a place and time he’d tried to put behind him. I think he finally agreed to bring me here as a sure way of curing me . . . or so he thought.

Maybe Emmet deserves some of the blame, too. If only he’d told me more about his former life, things might have turned out differently. I might not be huddled by the window, shivering in the cold after being chased out of my bed yet again by the night noises. I would’ve known more of what to expect here. Although Emmet is a verbose newsman known for his in-depth interviews, he clams up on personal matters. At first I was suspicious, sure he was hiding something from me, something too terrible to discuss. My overactive imagination caused me to wonder if I’d come to hate him after discovering whatever it was—a crazy wife in the attic, or a murdered one at the bottom of the lake. Then I wondered if I was being insensitive. Was his grief simply too raw, and his reluctance to discuss it only natural?

Emmet stirs in the bed, and I hold my breath until he settles back into sleep. I don’t want him to catch me prowling around in the dark again. He’s growing impatient with me, and I can’t blame him for that, either. I was the one who insisted we spend the summer at Moonrise. He tried to talk some sense into me. Let’s give everyone a little more time to get used to the idea of us, he’d said. His late wife had been dead less than a year, and our marriage had been sudden, unexpected. Everyone would come to love me, he was sure, but we should expect a bit of reticence at first. It was only natural, considering. At the end of August, said my sensible, reasonable husband, he’d take me to Moonrise for a week or so. Would that appease me?

No, it would not. Looking back, it astonishes me how stubborn I was, and how insistent. I’ve never been that way before. Like most women of my generation, I was raised to be a pleaser. Southern women don’t make many demands, especially of their men. But I made it clear that I wanted the two of us to spend the summer at Moonrise, and refused to settle for less.

At home in Fort Lauderdale, I presented my case: A summer away from the miserable heat of south Florida would be good for both of us. Since Emmet had never lived in Florida, he had no idea how brutal our summers could be. And I’d never spent any length of time in the Blue Ridge Mountains. It’d be cool at Moonrise, blissfully so, and wonderfully peaceful. Everything I’d heard about the little town of Highlands, where Moonrise was located, enticed me. And the house, I’d been told, had been vacant too long. The gardens were in ruins and the house was showing signs of neglect. Give us three months, and I felt sure we could restore everything to its former glory.

At that point in my argument, Emmet had placed his hands on my shoulders and turned me to face him. “Helen,” he’d said with a heavy sigh, “I wish to God you’d never found that damned photograph album.”

I couldn’t help myself. I laughed and embraced him, the tension between us dissipating as it always did when we held each other. He was right; that damned album had started it. I’d found it in a box of his things I unpacked when we moved in together, a collection of photos his late wife had begun putting into a scrapbook. Only a few pages at the beginning were filled; the rest were conspicuously, tragically blank.

Emmet’s response to my discovery of the album had caught me off guard. I’d been so sure he’d be pleased by my find that I’d barged into his office, something I never did. When we first married, I’d asked for photos in order to put faces with the names of his family and friends, whom I had yet to meet. Although I’d force-marched him through all of my family albums, his only contribution had been a few framed pictures of his daughter. With a shrug, Emmet told me that everything from his former life had either been put away or given to his daughter. When I found the album and photos I assumed he’d forgotten, he flinched but tolerated my questions. Yes, that was Rosalyn by the lake, on the dock sunbathing, pulling weeds in the gardens. And the others, their friends of so many years; couldn’t I guess who was who by the descriptions he’d given me? His eyes softened at an old picture of his daughter on her pony. She was ten in the picture, Emmet told me with a smile, and that pony turned out to be mean as hell. Horses, it was always horses with Annie, even then. But that was the extent of his indulgence, and he pushed away from his desk abruptly.

No question, finding the album started my obsession with Moonrise, the grand old estate with the wonderfully romantic name. Until then, I’d known little about the place, just that it was where Emmet had “summered” in his previous life, before he moved to Florida and met me. Located in western North Carolina, the property had belonged to the family of Emmet’s late wife, Rosalyn, and had become his by default when she died. I didn’t know anyone with a cabin in the mountains, much less an estate. It shames me now to remember how impressed I was, and how thrilled at the thought of having a mountain home of my own. I admitted to Emmet that it was something I’d always dreamed of having. Florida does that to you, I think. Living in a perpetual state of summer makes you long for changing seasons.

Only after we married did Emmet admit that Moonrise was an albatross around his neck, a burden he didn’t quite know how to handle. A magnificent estate in its day, it had lapsed into a sorry state after Rosalyn’s death. The property was tied up in a trust that barely provided for its upkeep, yet made unloading it next to impossible. He couldn’t afford it, nor could he bear to give it up. Although Moonrise held nothing but bad memories for him, Emmet wanted it for his daughter. And her mother would’ve wanted that even more. It had been Rosalyn, not Emmet or Annie, who had loved Moonrise so fervently, much more so than their home in Atlanta. Foolishly, carelessly, Rosalyn had not anticipated that Emmet, a few years older and in a highly stressful career, would outlive her and end up burdened with her beloved estate. If so, surely she wouldn’t have brushed off her lawyers’ pleas to take care of things lest the unthinkable happened.

Alone, poring over the snapshots in the album, I decided that Emmet had taken the pictures. Not only was he into photography, the pictures were black and white, his favorites to shoot. Most of them were taken from a distance, which I found so frustrating that I finally took a magnifying glass to study them more carefully, especially the ones of Rosalyn. This I did without a smidgen of guilt or morbidity, sure that any new wife would do the same. After all, this was the woman whom the man I loved had spent most of his life with, the woman he had loved with all his heart, by his own admission. She had died tragically, and too young. Naturally I was curious about her; who wouldn’t be?

In most of the photos Rosalyn’s face was obscured by a floppy hat or big sunglasses, but in one, Emmet had caught her perched serenely on the edge of an Adirondack chair with her fingers intertwined in her lap. She was smartly dressed in crisp white linen, a V-neck tunic over cropped pants, leather sandals on her shapely feet. This much was obvious: My predecessor was not a thing like me. That surprised me a bit, since I’ve been told that men tend to go for the same type. The only similarity I could see between Rosalyn and me was the color of our hair. Like me, Rosalyn had abundant dark blond hair, though hers was longer and a shade darker than mine, without the highlighted streaks. She was quite lovely, fine boned with long, elegant fingers and the graceful air of a prima ballerina. Her expression was serene if somewhat bemused, as though she and the photographer shared an intimate secret. Which, assuming it was Emmet, I suppose they did.

When I’d asked Emmet what his late wife was like, he’d given me a surprising answer. “You would have liked her, Helen. Everybody did. She was a wonderful woman.” That part didn’t surprise me; it was what he said next, after studying me for a long moment: “The two of you might look a bit alike, but you aren’t, really. Rosalyn was more . . . delicate, for lack of a better word. You’re a much earthier woman than she was.”

Now what did that mean, I wondered. The image it conjured wasn’t exactly appealing. I thought of big-boned peasant women bundling straw in the fields, or barefoot hippies, tiptoeing through the tulips. His observation sent me back to the photo album with my magnifying glass. Since Emmet was so reluctant to talk about his late wife, I’d had to piece things together on my own. Several weeks after our marriage, I’d finally met Emmet’s daughter, Annie, who was in her early twenties. Naturally I’d been curious about her, wondering if she took after her mother, but Annie was more like her father in both appearance and temperament. As for Rosalyn and Emmet’s close friends, I’d had phone conversations with them, but Rosalyn was rarely mentioned by any of them. Out of politeness, I’m sure, but their reticence only added to my curiosity.

Even if I hadn’t figured out that Rosalyn Harmon Justice had been born into wealth and privilege, it would have been apparent from the photos. In every likeness of her, good breeding was as obvious as a birthmark. The way she dressed, the tilt of her chin and jaunty lift of her shoulders, her understated beauty—all spoke of class. But it was more than that. It was also obvious that she possessed an enviable air of confidence, and an innate poise. I say “enviable” because confidence is something I sadly lack, and what little poise I possess is as hard earned and slippery as the proverbial eel. Poise, confidence, social ease; all are qualities I admire and have worked hard to cultivate, even though they remain elusive at best. Not only am I ill-bred, I’ve always been gauche and graceless, never at my best in social situations. No wonder I studied the photos every chance I got. Rosalyn was everything I’ve always wanted to be.

What I didn’t see in Rosalyn’s pictures was anything suggestive of fragility or delicacy. Why Emmet would refer to her as delicate was a mystery to me. Unless he meant ethereal, or otherworldly, but those terms were even more confusing. Based on her unwavering gaze into the camera, Rosalyn appeared to be the no-nonsense type. A woman secure in her own skin, there didn’t seem to be a thing hesitant or uncertain about her, unimaginable to someone like me.

Although I focused most of my attention on Rosalyn, I was almost as curious about the others in the album, the two men and three women who were Rosalyn and Emmet’s closest friends. All of them had summer homes in Highlands, and lived in Atlanta the rest of the year, as Emmet and Rosalyn had done. When Emmet and I first started dating, he told me about his friends, as lovers do while getting to know each other. Everything I heard about them—by all accounts a rowdy, fun-loving bunch—made me eager to meet them on one hand, and nervous on the other. After our marriage, they had called me to offer their congratulations, which made me even more eager to know them.

With the photo album in hand, I could put a face with a voice on the phone, or with one of Emmet’s anecdotes. There was one really good group picture of the six of them, dated the summer before Rosalyn’s death. I’d later learn that Emmet had taken it at Bridal Veil Falls, a sixty-foot waterfall near Moonrise. The group was posed together with the falls a stunning backdrop, like a silver scrim. I studied the photo and better understood the reason it pained Emmet to talk about those lost days. Everyone in the photo looked so happy, with no way of knowing that tragedy was about to tear them apart.

It seemed appropriate that Rosalyn stood in the center of the group, her arms stretched out as if to embrace everyone. In this photo she wore the large, face-obscuring sunglasses, the sun against her blond hair creating a halolike glow. Again she was in fashionable summer whites: knee-length shorts with a hooded top, the sleeves casually rolled to her elbows. On her right was the woman Emmet pointed out as Rosalyn’s closest friend, Kit Rutherford. Kit was the only one of them I hadn’t spoken to yet, and the others made a point of telling me she’d been traveling a lot. Even though Kit’d sent me a congratulatory card, I wondered if the real reason for her silence toward me was an ongoing grief for her best friend. After all, acknowledging the presence of a new wife meant coming to terms with the former one’s absence, and maybe she wasn’t able to do that yet.

Because Kit was turned partly sideways and in profile, I couldn’t tell that much about her. She, too, wore large sunglasses, and although her windblown hair obscured her face, she appeared to be quite attractive. She was a widow, Emmet told me, her much-older husband having died a couple of years before Rosalyn did. Kit and Rosalyn had been like sisters, he added, childhood friends who’d been inseparable since the day they met. As I’d suspected, he verified that Kit’d had the hardest time coming to grips with Rosalyn’s death.

In front of Rosalyn was a scholarly couple, Dr. Linc and Myna Varner, he a highly respected professor at the University of Alabama, and she a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet. Emmet winced when I showed him the picture because it showed Linc partly kneeling, one leg extended for Myna to sit on. Things have changed drastically for the Varners since then. On the eve of his fifty-sixth birthday, Linc—who’d always been in perfect health—had suffered a debilitating stroke. Since it happened only a few months after Rosalyn’s death, it was a further blow to the close-knit group. Although Linc’s tanned and agile in the photo, Emmet explained that he was now frail, and dependent on a walker. When I asked if the Varners were the most normal of the group, Emmet snorted and said that normality was a relative factor with that bunch.

The man and woman on the other side of Rosalyn, Noel Clements and Tansy Dunwoody, were the ones I found the most intriguing—and certainly the most attractive. According to Emmet, the two of them had been together as long as he’d known them, yet they weren’t lovers, and never had been. They were a stunning couple, especially seen next to each other. Noel was sunbright and tawny, a striking contrast to the dark-eyed, sultry Tansy. He had an arm crooked around her neck, and she was contorted in a playful pose. Despite their movie-star looks, it was their relationship that interested me. In Atlanta they lived at the exclusive Reid House, where each had their own flat (as they were called at such a ritzy place). In the summer, however, they shared a house together, right below Moonrise. And they’re not lovers? I’d asked skeptically. Emmet had waved me off in exasperation and said they’d have to explain their relationship to me. And if they did, could I kindly let him know because it’d never made a damn bit of sense to him, either.

Another photo showed a young woman who didn’t fit any of the descriptions of the folks I’d heard about. Judging by her startled expression, she’d been caught unaware as she hung a bird feeder from the eaves of a porch. Dressed in a flannel shirt, jeans, and work boots, this woman was strikingly different in appearance and demeanor from the rest of Emmet and Rosalyn’s sophisticated group. When I asked Emmet about her, he frowned as he took the album from me for a closer look. “Oh, that’s Willa McFee,” he said as his face relaxed into a fond smile. “I’d forgotten taking it. Probably the only one we have of her, she’s so camera-shy. A lot of mountain folks are.” Handing the album back, he explained. “Willa’s like family. Her mother was the housekeeper at Moonrise; now Willa’s taken over. Well, not as housekeeper—she’s the property manager, runs her own company. Matter of fact, she takes care of all of our places off-season, and does some housekeeping for us when we’re there. Nice girl. You’ll like her.”

The remaining pictures were of Moonrise, and I couldn’t get enough of them. Emmet told me that the estate was on a mountainside a couple of miles outside Highlands, and that it overlooked a lake. Looking Glass Lake, the original settlers of the area had called it, because of the way the water mirrored everything around it, or on it, so exactly. My favorite picture of Moonrise was one taken from the lake, looking up at just the right angle. Gothic in style and majestic in scope, Moonrise had the gabled roofs and turrets of a storybook castle. And the setting! A lifelong resident of south Florida, I peered longingly at the formal layout of shrubs and trees, many of which were unfamiliar to me. The foliage I was accustomed to was lush and tropical. Although I knew nothing about gardening, I could only imagine the upkeep of such majestic grounds.

A photo of the back of the house proved to be my downfall. Although I’d vowed not to bother Emmet with anything else about Moonrise, I had to know more about that one. The gardens in the back of the house had been photographed at night, in the light of a full moon. It was an eerily beautiful scene, unlike anything I’d ever seen. Although the leafy foliage of the garden was dark and mysterious, the moon illuminated white blossoms that grew everywhere—in every bed, border, shrub, and tree. Arbors hung heavy with flowering vines; pale blossoms encircled fountains and statuary; moonlit blooms lighted the graveled pathways like torches. I’d heard of moonflower vines and night-blooming cereus, of course, but I’d never seen anything like this. Those gardens had clearly been designed to be nocturnal, seen only by the light of the moon. Then it hit me. Moonrise! Did the name come from the garden, or was it the other way around?

I could hardly wait for Emmet to get home to ask him about the photo, and he was surprisingly patient in responding—initially, anyway. No, he hadn’t taken that one. He didn’t have the equipment for night photography, so Rosalyn had hired a professional. The photo was taken a few years back, when she needed one for a poster advertising one of her garden tours. And I’d guessed correctly; the house got its name from the moon gardens planted by Rosalyn’s great-grandmother, the original mistress of the house. Rosalyn took great pride in maintaining the unique gardens, a skill that had been passed down from her mother. The maintenance was so much work that few gardeners would’ve undertaken it without an extensive crew. At that point Emmet’s face changed and took on that guarded, remote expression I’d come to dread. “But all that died with Rosalyn,” he stated bluntly. “You’ve met Annie, so you know that, too. Rosalyn wasn’t able to pass her skill on to her daughter because Annie never had the interest. Maybe later, she might’ve come around.” He stopped himself and took a deep breath. “It would be better for all of us, Helen, if you’d let go of this obsession of yours. You’re stirring up a lot of things from the past that are better left alone. Trust me on this one, okay?”

And I might have done so, if it hadn’t been for a conversation I had with Noel Clements later that same night. It was early April, and I was still smarting from Emmet’s abrupt end to my probing into the life he led before I became a part of it. I’d answered the phone reluctantly, and even more so once I recognized the voice on the other end. Funny, I chatted freely with Linc Varner whenever he called, but was uncomfortable talking with Tansy and Noel. They were too glib for me, their urbane banter off-putting. With Tansy, I stammered like an ignorant Cracker and said the most embarrassing things imaginable. “I can’t wait to meet you, Tansy. I’m sure we’ll be the best of friends!” My blabbering would be followed by awkward, deadly silences. Finally, mercifully, Tansy would drawl, “I can’t wait to meet you, either, Helen. Ah . . . when did you say Emmet would be home?”

My conversations with Noel were worse, if possible. It never failed; I ended up gushing like a schoolgirl, then cringing at the sound of my voice. “Noel? Oh, hi! Hi! When will we ever meet face-to-face?” Noel was obviously the quintessential Southern gentleman, for he always made gallant attempts to rescue me from my blunderings. That evening, however, he had a ready comeback. Make Emmet bring you to Highlands this summer, he said, then all of us can meet the new bride. Not only would Moonrise fall apart if Emmet didn’t soon take care of it, so would their group.

“Tell the son of a bitch that we miss him,” Noel added gruffly. “The rest of us are taking the summer off, and we’re spending it in Highlands, just like the old days. That way we can have one last summer together before we all lapse into senility and old age.” Before he hung up, Noel threw in one last caveat. “And, Helen? If Emmet balks, tell him I said to think about Linc. We’ve lost one of our group, and come close to losing another. The truth is, none of us knows when our last summer will be. Tell him he owes it to Linc.”

When I repeated Noel’s message to Emmet, he dismissed it without further comment. He hadn’t been back to Highlands since Rosalyn’s death, though he’d halfheartedly promised to take me. But in dismissing Noel’s request, Emmet made the mistake of using our jobs as an excuse, not realizing how I’d pounce on that. Seeing how badly I wanted to go, he hedged, he’d be tempted if only we weren’t tied down to our work.

I began plotting the very next day. Surely if I set everything up with our jobs, made it easy for the two of us to get away for an extended period, Emmet would have to agree. Both of us worked at the same TV station, on the same show, even, which made it easier than if I’d had to deal with two different situations. Besides, Emmet was such a big shot at the station that they’d never deny their prized newsman anything. I moved quickly, and everything fell into place. I was given permission to tape my cooking segments in advance, and Emmet could do his news commentaries from an affiliate network, whichever one was closest to Highlands. Everything worked out so well I convinced myself that it had been intended. By the end of May, our town house had been sublet and our bags packed. We would be spending the summer in Highlands, North Carolina.

Yet here I am, several days into the summer I was so determined to have at Moonrise, huddled in the darkness and wondering what’s wrong with me. I can’t sleep; I’m hearing voices, and I lie to Emmet every time he asks me if I’m happy that we’re here. He doesn’t question my lies, and why should he? From his point of view, I’d wanted to be at Moonrise so badly that I was blind to the risks involved.

What he can’t know is, I had known the risks; I’d just ignored them. The thing was, I’d just gotten through a really bad time in my life when I met Emmet Justice. It was a meeting that turned both of our lives around. He and I had little in common, and neither of us was looking for a relationship. Yet we’d fallen so deeply in love that we’d hastily—and some might say foolishly—cast our lots together. We were just settling into our lives with each other, and we were happy, goofily, giddily so. I was more at peace than I’d been in a long time, maybe ever, and I believed Emmet to be also. So what did I think I was doing, bringing Emmet back here? Here, of all places, where the ghosts of his past lived on? No wonder I was so restless. Emmet had been right. By bringing us to Moonrise, I’ve stirred up things that would have been better left alone.