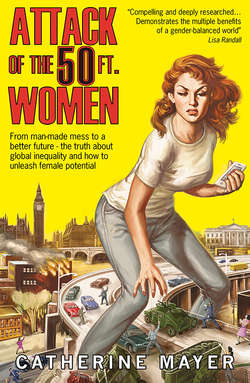

Читать книгу Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: From man-made mess to a better future – the truth about global inequality and how to unleash female potential - Catherine Mayer - Страница 8

Chapter One: Gate-crashing the club

ОглавлениеDOWNTRODDEN PEOPLES CLAIM superior qualities to compensate for inferior status. Women cling to a belief in essential, female difference. We are emotionally intelligent. We are nurturing. We work together rather than against each other. We can multitask. Want something done? Ask a busy woman.

The early months of the Women’s Equality Party appeared to reinforce this thesis. Each successive gathering of our newly formed steering committee brought a banquet to the table, of energy, ideas, sweet concord and food – so much food.

Sandi came with herrings: pickled herrings, herrings in a sweet mustard and dill sauce, herrings in soured cream, and pumpernickel already cut to carry satisfactory consignments of herring from plate to mouth without need of forks. Others baked cakes from scratch. I supplied alcohol.

Each meeting also brought long lists of tasks completed without reminders, despite multiple commitments tugging at sleeves. One of the most time-consuming jobs involved answering the unstanchable flow of emails that news of WE had triggered. Volunteers often worked through the night, their exhaustion mitigated by the enthusiasm of the correspondence.

‘Thank you for giving me something to believe in again.’

‘At last, something to get excited about in politics!’

‘For the first time in my 14 years of not bothering to vote I am inspired.’

‘I am 16 years old and passionate about feminism. I would love to be a bigger part of the worldwide fight for women’s equality!’

‘I am so excited about this party – I’ve waited my whole adult life for it.’

‘YES PLEASE, this is just what we have needed for such a long time. I’m on board, we have much work to do, please delegate.’

To delegate, you need a structure. We created an organisation from scratch and then scrambled to update it as needs and priorities changed, sprouting subcommittees to formulate policy and deal with press, social media, outreach, fundraising, finance and the demands that bureaucracy ladles onto the political process.

Britain is generous with its portions of red tape, far more so than many other nations. In July 2015, I met up with Sunniva Schultze-Florey, who had also co-founded a new political party four months earlier. Inspired by Sweden’s Feminist Initiative, she and a small group of friends started a Norwegian offshoot, Feminist Initiative Bergen-Hordaland, and they were already preparing for their first elections, for local government, in September. They didn’t need to do much more to make the party official than to announce its existence; they didn’t have to raise money for deposits to run, just collect a certain number of signatures. Norway’s proportional voting system meant the entry level for new parties didn’t seem too daunting – only a few thousand votes to win a council seat.

As our Norwegian counterpart plunged into campaigning, we jumped through hoops just to secure the right to campaign, an exercise as questionable as a dolphin show at a water park – and as anachronistic. Politics in the UK doesn’t just look and sound like a club. It is a club, with rules designed to exclude the wrong type of person as defined by the type of person who already belongs to the club. A new party cannot open for membership or put up candidates for election until registered with the Electoral Commission. That involves writing a constitution and rules of association and appointing officers. You must also establish a company and then find a bank willing to accept your business, because a party is also an enterprise. Quite a few bankers sucked pens and stared skywards when confronted by a start-up enterprise without a business plan or guarantee of income.

You can see why they might worry. The club rules ensure it’s hugely expensive to do politics. There are deposits to be paid for each candidate – £10,000 to stand for Mayor of London! A further £10,000 to appear in the official brochure that goes out to voters! Turn again, Whittington: the road to London’s City Hall is truly paved with gold.

Campaign costs are eye-watering, especially in first-past-the-post elections such as Westminster’s, where the overall number of votes across the UK matters less than the concentration of votes in individual constituencies. In the May 2015 general election, UKIP picked up one in eight votes, almost 3.9 million in total, but won only a single seat. The Scottish National Party gained 1.5 million votes and 56 seats. To successfully challenge old parties, newcomers must finance not only profile-raising marketing and PR campaigns but also street-by-street, door-by-door drives, reliant on volunteers and paid expertise, and underpinned by pricey technologies.

There’s another way in which money talks. One reason politics is dominated by affluent men in suits is that candidacy is expensive and risky. It’s far easier for people with private incomes or salaried jobs that grant leave of absence to run, and that’s assuming they aren’t caring for children or elderly relatives. The Women’s Equality Party wanted to support women to become candidates, not only by paying their deposit money but also by providing bursaries to help with childcare and other costs.

So we were eager to open for membership as soon as possible to establish the revenue stream necessary to do this – any of this. We needed funding just to collect funds. The Electoral Commission allows political parties to accept donations over £500 only from permissible donors: UK-based companies and individuals registered on a UK electoral roll. The regulations are intended to stop foreigners and tax exiles from buying influence in British politics – no representation without taxation, as it were – but do nothing of the kind. Any global corporation with a UK subsidiary is entitled to donate, no matter how breathtaking its tax-minimising schemes. Any person rich enough to stash wealth offshore is probably also rich enough to find channels to donate.

Yet WE risked penalties if, say, a British national living in the UK but not registered to vote gave a series of small donations that in total breached the £500 threshold. The only way to guard against such accidents is to check would-be donors against the electoral register, which inevitably isn’t a conveniently centralised electronic list, but a series of lists held by local authorities. Sian McGee, a new law graduate and youngest member of the original steering committee, became WE’s first paid employee, hired to perform these checks. She immediately spotted a potentially dodgy transaction. The party had launched a time-limited founding membership scheme, ranging from £2 a month to £1,000 and upwards for lifetime membership. Sandi enrolled online for the latter option but Sian could find no Toksvigs on the electoral roll. She could not know that Sandi’s information is withheld since a stalker broke into her house. Sian diligently rang Sandi to query her eligibility to help found the party she had founded.

The final hurdle to gaining official party status involved seeking the Electoral Commission’s approval for our logo and slogan for use on ballot papers. Two wonderfully talented designers, Sara Burns and Jeanette Clement, volunteered to produce a logo for us. They had never met before joining the steering committee, but instantly devised a way of working together, and celebrated that collaborative spirit, and the party’s aims, with a design that turned the E of WE into an equal sign. They chose a palette not in use by any other party – green, white and violet, the colours of the Suffragette movement. The committee then voted on a range of slogans and landed back on the one I had written for the public meeting back in March: ‘Because equality is better for everyone.’

This book aims to test that proposition. It might appear that the only point of debate relates to men and whether by ceding their dominance they would really gain more than they lose. The rest seems self-evident.

Inequality is yawning and its impact is disfiguring. The gap between rich and poor countries, and between rich and poor, is widening. One per cent of the global population owns more wealth than everyone else on the planet combined. Not even the one per cent look happy about this state of affairs as they transfer from one hermetically sealed bubble to the next, ringed with security lest real life accost them. In rich countries, the poor struggle daily to survive. As many as a fifth of Britons live below the poverty line, as do more than 15 per cent of Americans. Social mobility is stalling. Social unrest is deepening. Conflicts spill across borders and reach out violently into distant city centres. Many of the people displaced by those conflicts, some 65.3 million on current estimates, seek shelter in countries already lacking resources; 86 per cent of the world’s refugees are lodged in the developing world. Migrants reaching Europe should expect a mixed reception. Any dreams of universal live-and-let-live tolerance are dissipating as populist hate-mongers and extremist movements find, in their supposed polarities, common cause against liberalism.

Surely if we successfully dismantle the patriarchy, the biggest structural injustice of all, other structural injustices must also begin to crumble. Surely a more gender-equal world will be a more equal world in other ways too.

Yet from the start of WE, easy assumptions frayed. Our first steering committee meeting took place at my central London flat, in my kitchen. We sat around an extendable table owned by my family since 1933, when my widowed great-grandmother started dealing antiques from her front room in a Chicago suburb during the city’s Century of Progress International Exposition (a World’s Fair with the motto ‘Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Adapts’). The table tells a story not just of female entrepreneurship, but of comfort. My middle-class family, émigrés to the US, not refugees, lived in homes large enough for such a table.

There were ten of us at the first steering committee meeting. Not every woman (and neither of the men who joined us) had been born to the same level of advantage, and none of us had problem-free lives. Between us we wrestled with disability, physical and mental health issues, had experienced racism, homophobia, ageism and abuse. Still, we all enjoyed the luxury of political activism. Entry to the steering committee rested on two qualifications: an enthusiasm for the idea of the party and a commitment to getting it started. Many women are too busy with low-paid work or unpaid caregiving to spend time trying to fix the problems of women in low-paid work or unpaid caregiving. Our participation in the committee defined us as an elite, and we knew that to build a representative party we needed to be a representative party at the core. It would take us longer to appreciate the scale and complexity of that task.

As the committee recruited additional members, and culinary contributions became more elaborate, we had to look for other venues. The size of my table wasn’t the issue. Mandy Colleran, an actor and activist, used a motorised wheelchair that could not navigate the narrow doorway to my flat. Other members volunteered to host, but every alternative venue revealed structural impediments that able-bodied residents hadn’t appreciated. A lift in one apartment block proved too small. Another disabled committee member offered her flat but its front steps defeated Mandy’s chair. There are degrees of disability as there are degrees of inequality. Many impediments are visible only to those whose path they block.

Mandy is a coruscating speaker, painfully and often hilariously direct in her opinions. She spoke up at our first public meeting and again at the second, held at Conway Hall, since 1929 the home of the Ethical Society and a fulcrum of liberal activism. Its CEO, Jim Walsh, had quickly decided to support the nascent Women’s Equality Party by making the auditorium available to us for events at low rates with deferred payment. Unfortunately, Conway Hall’s precarious income and listed building status meant that, although it is fully accessible for audience members in wheelchairs, there is no ramp to the stage. We decided against using the stage for that event and anyone who wanted to speak did so from the floor. Sometimes equality is about finding a level that works for everyone. A lot of the time, it’s more complicated than that.

At first we plundered our own address books to grow the party but our London base risked a London bias. It has been exciting to watch the idea spread to other parts of England and to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and in each context to define different sets of priorities within our unified commitment to change. Committee members’ combined circles encompassed a wide range of professions and experiences, even if they were a little heavy on entertainment, media and politics. My friends and contacts came in all shapes, sizes and flavours. If asked, I might well have described them as diverse.

That’s because it’s easy to misunderstand diversity. One friend, a senior figure in the media, explains it well. He is hugely talented, but knows that the fact he ticks some ‘diversity boxes’ made the companies that employed him look good without actually challenging their culture. He speaks and acts like a member of the establishment club despite a mixed-race heritage and comprehensive-school background. He learned to minimise differences, to put people, including people like me, at ease. ‘Frankly, as one black friend who has risen a long way in politics put it to me, we don’t frighten the horses,’ he says. The point he is making is that for organisations to benefit from diversity, be they corporations or political parties, they must accept and value the discomfort of difference. It’s pleasant when your colleagues agree. It’s often more productive when they challenge.

Diversity isn’t always visible, and, as my friend pointed out, visible diversity is by no means enough, but it does matter. Groucho Marx famously sent a telegram to a Hollywood club: ‘Please accept my resignation. I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member.’ Most people aren’t by instinct Marxists. They care to belong only to clubs that appear to accept them.

Women aren’t just excluded from politics by a lack of time and money. Many are put off by the way it looks and sounds because they cannot see or hear themselves in its monotone braying. In launching a political party that took as one of its core objectives the equal representation of women – that itched to throw open the doors of public institutions and of private enterprises not just to more women but to a wider range of women – we needed to ensure we didn’t replicate the deficiencies of the existing system. This couldn’t be just a party for friends and friends of friends, for like-minded people who felt comfortable together. We had to incorporate visible and invisible diversity, to attract the widest possible engagement, and to engage as an organisation with all of those perspectives.

One form of diversity you can’t see is that of political allegiance. By having people of divergent political persuasions around the table and opening our membership to members of all other democratic parties, we intended to identify the tracts of common ground between those parties on gender equality, and either work with them or, by winning votes away from them, spark them into copying our policies.

It wouldn’t be enough to be a broad church – and we were anyway unlikely to become one – if we failed adequately to address the issues that divide the women’s movement within itself and from other movements. ‘When feminism does not explicitly oppose racism, and when anti-racism does not incorporate opposition to patriarchy, race and gender politics often end up being antagonistic to each other and both interests lose,’ wrote American academic and civil rights activist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1992.1 She had coined a term, ‘intersectionality’, to describe the ways in which disadvantages such as race, gender, class, religion and age intersect and intensify, and she also proposed frameworks to enable collaborative and mutually beneficial advocacy among disadvantaged groups. Her observation was both true and prophetic, in good ways and bad. America’s 2016 elections highlighted deep splits among female voters, and the sharpest related to race. Ninety-four per cent of black women voted for Hillary Clinton; 53 per cent of white women voted for Donald Trump.6 Black women needed no coaching to understand the dangers a Trump presidency represented to them. Large numbers of white women succumbed to a cocktail of ingrained misconceptions and prejudices. They – we – are taught throughout our lives that white men have a grip on power and wealth and that the easiest way to share in those benefits is to align with them. We are inculcated with the lie that equality is like a cake: if you take a piece, there is less for me. We also absorb the propaganda that calls into question the abilities of our own sex to lead, just as we will all have picked up racist attitudes.

No wonder feminism divides along these lines – and how urgent it is that white women learn, fast, to recognise where our true interest lies, in building a world that works better for all women and, indeed, for all genders. Kimberlé Crenshaw created an essential framework for thinking about how we should do this. The most effective organisations combatting misogyny and racism take an intersectional approach, but women of colour are apt to recoil from the embrace of white feminists who presume to speak for them rather than giving them the floor.

Long before white women helped put Trump in the White House, anger at clumsy patronage, and at the allied phenomenon of wealthy women presuming to understand the priorities of the poor, had become so intense in corners of feminism that the phrase ‘white, middle-class feminist’ emerged as a potent insult. In 1983, the novelist Alice Walker coined the term ‘womanist’ as an alternative to white feminism. ‘How can you claim the label of those who would oppress you to see their goals realised, even when commonality exists in some areas?’ asked the blogger Renee Martin three decades later, in an essay explaining why she, as a black woman, rejects the term ‘feminism’.2 Commonalities are not enough to stop movements that can only succeed through cohesion and volume from splintering.

Sandi and I – undeniably white, irretrievably middle class and irrevocably feminist – of course drew fire. The criticism helped us to focus on the issues underpinning it. Just as men lack a visceral understanding of the female condition, so women leading reasonably comfortable lives may not automatically grasp what it is to suffer multiple oppressions. How could we as activists in our own flurry of activity avoid taking up space that others, less privileged struggle to claim? Were we entitled to found a party or was this action proof of entitlement, in the negative sense of the word?

The answer – or at least one answer – is that it depends what the party does and achieves. Another is that the appropriate response to critics of white, middle-class feminism cannot be for every white, middle-class feminist to down tools. That would be to fall into a similar trap as the white, middle-class anti-feminists who deny the evident and urgent need for greater gender equality at home because there are more acute examples of misogyny elsewhere. Nimco Ali, one of the first members of the steering committee, was attacked in some quarters for joining the Women’s Equality Party, and later subjected to particularly vitriolic abuse during her 2017 general election candidacy for us. She points out that the black, Asian and minority-ethnic population of the UK stands at less than 12 per cent. This means, she says, that ‘there are going to be women at the forefront who are white, but it’s how they use their privilege and platform to have that conversation.’3 To acknowledge that some women need less help than others is not to deny that all women need help. The question is how to be helpful.

I got to put that question to Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw herself in May 2016. She had come to the UK as a guest lecturer at the London School of Economics, on furlough from an extraordinary range of jobs and commitments: her law professorships at UCLA and Columbia, and the recently formed Congressional Caucus on Black Women and Girls, as well as from her executive directorship of the organisation she co-founded, the African American Policy Forum (AAPF), and from #SayHerName, the campaign she and the AAPF had started the previous year with other organisations to draw attention to the black women killed by police and overlooked by the Black Lives Matter movement. She’d arrived in London just two days before but managed to lead me to one of the few good, tourist-free bars in Covent Garden.

She laughed at my question, then sighed. ‘Well, you have your work cut out for you,’ she said. ‘I think there has to be a lot of work on all sides and that’s the work of coalition and that’s hard.’ She gave generous, practical advice about how to do the work, and much encouragement, but also slipped in a warning. ‘I’m suspicious of privileged women who just go: “Yes, you’re absolutely right.” And have nothing to say beyond that. You have to engage deeply. I want people to ask and question if they don’t feel it, so that you can have the fight, you can try to resolve it. So, it’s kind of about having to find some agreement among those of us who feel Othered and are Othered: What is it that we want to see? What is it that we want to find agreement on? What is it that shapes our agenda?’4

It took an effort of will not to respond ‘you’re absolutely right’, for the sake of the gag and because she absolutely was. It would never have been possible to build an effective organisation from my kitchen table. We had to go out and reach out, involve an ever wider demographic and, crucially, find ways to create an internal democracy that gave full weight to each of those voices without slowing momentum or losing sight of the reasons for starting the party in the first place.

We’ve made progress but nowhere near enough. Pushing for diversity isn’t the same as achieving it – an obvious point but one that bears repeating because of the frequency with which organisations quote their diversity policies as supposed evidence of diversity. The process can be long and is littered with obstacles that I have come to understand much better

Right at the beginning, perhaps two days after proposing the party, I called a friend and fellow journalist, Hannah Azieb Pool, and attempted to persuade her that she should lead it. My thinking was simple – to the point of naivety. I asked myself ‘would I vote for her?’ and the answer was a resounding yes. Would she appeal to voters of all genders, classes and ethnicities? I thought so. Eritrean-born, adopted by a white family in Manchester, she was in a position to speak to the universalities of female experience and to the specifics of intersectionality – the ways in which that experience is changed or impacted by other factors.

Hannah thanked me, and said she’d ponder. A few days later she declined, with expressions of regret. She had too much going on, too many commitments. Straining to hear her as I stood in a noisy airport, phone clasped to ear, I tuned out the background hum of things unsaid. It was only recently that I summoned up the courage to ask her if she had spared me a more brutal response. She explained that the reasons she gave were genuine but that the deciding factor had been risk – and the risks would always be greater for black women. The animus she’d attract from trolls and anti-feminists would comingle with racism, while some strands of black activism would inevitably label her a sell-out.

WE represented a leap in the dark and, while she trusted Sandi and me, she couldn’t be sure how the party would evolve around us. After working at the Guardian, she knew that organisations sometimes mistake good intentions for good practice. I also hadn’t factored in the economic hit she’d take in spending time party-building. If we asked her now, she might be more inclined to say yes, she added kindly.

There were other barriers to overcome. Some people who came on board kept their support quiet because they were members of parties less enlightened about collaborative politics. Even so, every day brought a fresh crop of outrageous talents to my kitchen table. This, we realised, is what politics might be if it weren’t such a narrow club. All the candidates WE has fielded so far are new to politics, extraordinarily gifted and extraordinarily different to each other. The steering committee crackled with ideas and energy.

Even in this crowd, Sophie Walker was an obvious standout. I had invited her to speak on equal parenting at our first ever public meeting. She held the attention of the room in a way that only natural communicators can do. In April 2015 the steering committee elected Sophie leader. The vote was unanimous and unanimously enthusiastic. In August, on the day she came to work at the party full time, leaving a job at Reuters to do so, she and Sandi and I lined up for a joint portrait in the King’s Cross offices of the Guardian.

We might have been re-enacting the ‘Class Sketch’. First performed in 1966 on David Frost’s satirical TV show, The Frost Report, the skit featured tall, gaunt John Cleese peering down his nose at the shorter, stockier comedian Ronnie Barker. ‘I look down on him, because I am upper class,’ Cleese says. Barker returns his gaze: ‘I look up to him, because he is upper class. But …’ He swivels to stare at five-foot-nothing Ronnie Corbett. ‘I look down on him because he is lower class. I am middle class.’ ‘I know my place,’ deadpans Corbett.

Sophie, at well over six foot and skinny, is Cleese to my Barker and Sandi’s Corbett. Stand us next to each other, and the effect is pretty funny. Some of our critics laughed at us, rather than with us. They depicted the Women’s Equality Party as a joke and the joke was that we were all middle class. ‘Sandi Toksvig’s Women’s Equality Party is a middle-class ladies’ campaign group doomed to fail,’ read one headline.

That neatly summarised the message of the Guardian feature that accompanied the photos, written by a journalist called Paula Cocozza.

We arrived for the interview and photo shoot after a full morning of meetings in my kitchen. We’d strategised our approach to a fundraiser that evening and discussed Stella Duffy’s proposals for extending our reach beyond our initial catchment. The first person to sign up to the party on Facebook, and an original member of the steering committee, Stella was our branch-builder and queen of email-answering, directing the enthusiasms of would-be supporters into practical steps, and often pulling all-nighters as she attempted to combine her commitment to WE with her work as an author and the founder of the community arts and science project, Fun Palaces.

A chunk of the morning before the Guardian interview had also been devoted to making progress on policy, a consultative process harnessing the input of our rapidly expanding branches, grassroots organisations, campaigners and experts. We ran through a to-do list that included pinning down the date and detail of our autumn policy launch, and figuring out the logistics for a series of membership and fundraising drives, including a potential partnership with the producers and distributor of the movie Suffragette. We discussed merchandising possibilities too. We needed money, we needed staff and we needed offices.

The flow of emails, far from slowing, had multiplied and diversified. In addition to offers of help and declarations of enthusiasm, we now received endless press bids, queries from organisations working in overlapping fields, and approaches from politicians from other parties wanting to scope us out. Many of these communications betrayed false assumptions about the size and resourcing of WE. Correspondents complained if they didn’t get a response within 24 hours. One group asked us for a donation.

We were certainly more organised than we had been. Our subcommittees still relied heavily on volunteers, but this situation was clearly unsustainable – for the party and the exhausted volunteers. In addition to Sian, we now had a fierce and forensic Treasurer, Samantha da Soller, and a secret weapon, Polly Mackenzie, a Liberal Democrat who had until the recent elections served as Deputy Director of Policy at 10 Downing Street for the coalition government and had come to us as a consultant. Marketing and public relations support came from Andrea Hartley and her company Skating Panda. She had apologised to me after the March public meeting: she loved the idea of the party but didn’t have time to help. A few days later she emailed to say she didn’t have time to help but would do so anyway.

In Sophie we had that most precious of assets – a leader, a natural and inspirational leader. When she spoke, people listened and wanted to listen. She could run meetings, an underrated skill essential to an evolving organisation. She had already cut her campaign teeth pushing for better treatment for her daughter Grace, whose Asperger’s Syndrome went undiagnosed for years, in part because the condition is assumed not to affect girls. Sophie had become a potent advocate and activist, and ran marathons to raise money for autism charities. In her blog, Grace Under Pressure, later published as a book, she documented struggles with public services and schools, and her daughter and herself. Running had also helped to rescue her from depression. Divorced from Grace’s father, and for a considerable time a working single mother, she remarried, acquiring two stepsons and a second daughter. She spoke at the first WE meeting about her experiences of juggling work and family in a system and society that sees childcare as a matter for mothers alone.

Her parents attended university, the first members of working-class families to do so. After state school in Glasgow, Sophie also went to university, Reading. She found a way into Reuters via a short-term contract and remembers her conversation with her future boss when the company decided to move her onto permanent staff. ‘I’m always interested in people who get in by the back door,’ he told her.

Cocozza didn’t see in Sophie a woman who got in by the back door. If the author’s impressions aligned with her expectations, we carried some of the blame – literally. Three ‘white, middle-aged, middle-class’ women, we arrived with bags of white, middle-aged, middle-class food.

Sandi, handing out Pret A Manger sandwiches, appeared to Cocozza’s eyes ‘mum’, whereas I defined myself as ‘the most obvious politician of the three’. This is not a compliment, nor is it ever the business of the Guardian to dole out compliments.

That didn’t stop us from wincing as we read the piece because it reinforced precisely the narrative we’d been hoping to change. ‘Listening to Toksvig, Mayer and Walker, clues arise that suggest they may not be able to hear how their assumptions can shade into complacency,’ Cocozza had written. ‘Their language is encoded with a privilege they appear not to notice … It all suggests difference of the wrong kind: that the life experiences of Mayer, Toksvig and Walker may be alienatingly divergent from the people they want to reach.’5

On the day of publication, membership applications skyrocketed. The only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.

While Cocozza and others, ourselves included, worried whether we were too privileged to pursue politics effectively, another school of thought predicted the Women’s Equality Party would dissolve into a puddle of sugar. An article in Spiked greeted our founding with a call for an end to feminism under the headline ‘The Women’s Equality Party: for ladies too nice for politics’. ‘Women’s Equality Party needs a strong dose of Nigel Farage’, advised the Telegraph. ‘The Women’s Equality party has a problem – no one hates it’, a second Guardian piece declared.

If any of us resented these accusations – how dare they call us nice! – we bit back the responses that might have punctured our ladylike image. Several of us had tweeted our criticisms of Cocozza’s piece and then regretted doing so. For one thing, we were determined to treat journalists with courtesy, and not only because some of us were journalists. We were setting out to do politics differently and to develop a style and sensibility distinct from the male-dominated old guard. That difference showed itself in small touches. Sandi accepted the title of ‘MC’, a role hitherto absent from party politics. Would she be master or mistress of ceremonies, I asked her? ‘It depends on the day,’ she replied.

More ambitious was our desire to resist the combative culture that simultaneously unites and divides Westminster hacks and media managers. Like most members of the parliamentary lobby, I’d learned to expect abusive calls and texts from special advisers as part of my job. Parties often employ human attack dogs who attempt to secure the coverage they want by shouting or threatening to remove access. After reading Cocozza’s piece, I couldn’t help laughing at a memory that bubbled to the surface. In 2008, I’d gone to the pub after putting to bed my first long TIME cover story on David Cameron. The feature explained that the Conservative leader looked set to become Prime Minister, but his rise in the polls and a recent by-election win by a posh Tory candidate did not mean that his gilded past had lost the power to haunt him. I’d tracked down a contemporary of Cameron’s in Oxford University’s Bullingdon Club who described a night on the tiles with the wealthy student and his similarly privileged fellow members as ‘Brideshead Regurgitated’. ‘Champagne memories and social deprivation could make for an uneasy juxtaposition, especially in such tough times. Can someone marinated in plenty viscerally understand what it feels like to be poor or excluded?’ I wrote. ‘[Cameron] brushes the question aside with visible irritation. “I don’t have this deterministic view of life that you can only care about something if you directly experience it,” he says. “You can’t walk a mile in everybody’s shoes.”’6

Before leaving my office, I’d emailed a copy of the cover image, but not the text, to Cameron’s then director of communications, former News of the World editor, Andy Coulson. In UK editions, the cover would run with the gnomic headline ‘Behind the Smile’. Outside Britain we’d chosen a more direct line, assuming people might not recognise our cover star: ‘David Cameron: A Class Act’. Coulson didn’t like the pun at all. He called me to deliver a long ticking off. I recall standing outside the Fox and Anchor as his voice issued tinnily from my mobile phone: ‘Class no longer matters to voters!’

At the Women’s Equality Party, we resolved to handle media politely but also firmly. One of our core objectives is equal treatment by and in the media, a huge and urgent issue for women and for democracy that I’ll explore in depth later in this book.

A small but significant part of that objective relates to the ways in which political coverage skews against women. The gladiatorial contests that broadcasters prefer over reflective, conversational interviews benefit neither politics in general nor women in particular. Why should politicians be judged on their ability to withstand a barrage of questions, or the same question repeated as the interviewer attempts to extract an answer that he – aggressive interviewers are most often men – likes better? Do we prefer leaders who speak quickly or think deeply? This style of journalism reflects male priorities, male socialisation, and even women skilled at debating are always at a disadvantage. Studies show that audiences react quite differently to men and women taking the floor. Men gain respect, women attract animosity.7

Hillary Clinton speaks more softly than either Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump, yet she was accused throughout her presidential campaign of shouting. As Secretary of State, Clinton’s popularity ratings were high. They dropped as soon as she confirmed her run for the White House.8

This response wasn’t confined to male voters. Women are products of the same sets of social messaging, programmed in varying degrees to defer, to support, and that’s only the start of the problem. The harder we try to slough off patriarchal programming and determine for ourselves what it means to be female, to be a woman, the more our synapses begin to fry. Where does biological sex end and constructed gender begin? What are intrinsically female qualities?

We know that it is an insult to be called ‘nice’ in the political context, yet in that same context, as feminists, many of us would go to the barricades to assert our niceness. We assume it is the superpower the new breed of 50-foot women could bring to bear. We imagine Equalia would be a nice place because a gender-balanced society would enable men to relax and discover their own niceness in a gentler, feminised culture.

The ease with which the steering committee achieved consensus at its earliest meetings seemed to bear out this notion. Then came an argument. We tussled over the future shape of the organisation, and afterwards everyone around the table looked stricken. In raising our voices to defend beliefs, we had inadvertently challenged one of the unspoken shared beliefs that brought us together. True, the disagreement led to better decisions, but maybe the sexes weren’t so different after all.

Did we, as women, really bring something unique to the table? The next chapter looks at what happens if those tables are not kitchen tables but Cabinet tables.