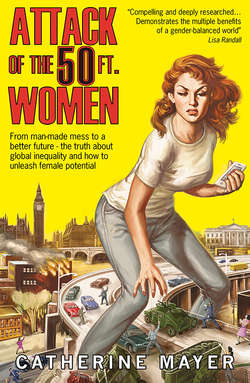

Читать книгу Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: From man-made mess to a better future – the truth about global inequality and how to unleash female potential - Catherine Mayer - Страница 9

Chapter Two: Votes for women

ОглавлениеIN 2008, A YOUNG Labour Party activist from London travelled to Raleigh, North Carolina, to help Barack Obama win the White House. Hannah Peaker believed in descriptive representation – that it isn’t enough to elect lawmakers to advocate for us; at least some of our representatives must also share characteristics and perspectives with us if legislation is to be properly attuned to our needs. The Democratic primaries posed a quandary in this respect. Did the United States more urgently require a black President or a female one? Both firsts seemed long overdue, and the debate had quickly descended into rancour.

‘Gender is probably the most restricting force in American life,’ wrote Gloria Steinem in a piece arguing for Hillary Clinton.1 This sentiment from one of the most prominent leaders of second-wave feminism kicked off a self-mutilating game of Who’s More Oppressed Than Whom. After it rumbled on for nearly a month, Kimberlé Crenshaw co-authored a riposte with the author of The Vagina Monologues, Eve Ensler, pointing out the false polarity. ‘We believe that feminism can be expressed by a broader range of choices than this ‘either/or’ proposition entails ... For many of us, feminism is not separate from the struggle against violence, war, racism and economic injustice.’2

Hannah did not believe that misogyny trounced racism or that getting any woman elected would inevitably help women. Her view was that descriptive representation creates better democracies by more closely reflecting the complexity of the voting populations. However, she had already witnessed in British left-wing politics the magical queuing system that keeps gender from ever reaching the head of the line. She had also seen women held to higher standards than men – and judged more harshly than men – because of their rarity. She wasn’t enthused by Hillary Clinton, but she didn’t think Clinton deserved the venom spat in her direction. In choosing to help Obama, Hannah hoped to support a politician who seemed as if he might, in Crenshaw and Ensler’s terms, ‘work to abolish the old paradigm of power’. Patriarchy lies at the core of that paradigm.

By the time Hannah headed to the States, Obama had defeated Clinton and teamed up with Joe Biden. They were rising in the polls against the Republican Party’s John McCain and his surprise choice as a running mate, Sarah Palin. Obama’s ground campaign looked impressive. Hannah arrived in North Carolina with just a change of clothes and an address on a piece of paper. Within 24 hours, she had digs in a house loaned to Obama’s local team by supporters, a bellyful of barbecued meat from a fundraising cookout, boxes of Obama t-shirts, hats, stickers and leaflets, and an itinerary. She would be working in Raleigh campaign headquarters but her new colleagues wanted her to meet the voters first.

‘They sent me out canvassing because they thought this whole thing was hilarious: this British girl knocking on people’s doors,’ says Hannah. ‘People just couldn’t understand what on earth I was doing there. Why had I come to campaign for their President? There’s very little travel outside of the state much less the US.’ Door-knocking in North Carolina held dangers she had never encountered on the other side of the Atlantic. After a brace of gun-toting Republicans bared their teeth and set their dogs on her, she approached the task with circumspection.

When yet another red-faced man answered the door with a shotgun in the crook of his arm and dogs circling his legs, Hannah instinctively began backing away. Still she delivered her opening line. ‘Hey, sorry to disturb you. Are you going to be voting for Obama?’

‘He’s like “What?”’

‘Are you going to be voting in this election, sir?’’ Hannah mimics herself, the question starting softly and tapering to a near-whisper. ‘He’s like “You with Obama?” I’m like “Yeah”.’ She mimes cowering. ‘I was wearing an Obama jumper and baseball cap.’

She had started to calculate the time it would take to sprint from his porch to the gate when he spoke again. ‘So me and my boys, we’ve voted Republican our whole lives. But Sarah Palin is on the ticket. I said to them “Would you want your wife to be President?” And they said “Hell no.” So we’re going to be voting for Obama.’

‘OK,’ Hannah replied, simultaneously relieved and horrified. ‘Have a badge. Welcome on board.’

This attitude wasn’t isolated. The racism that flamed so fiercely throughout Obama’s two terms of office sometimes tried to mask itself during his initial run at the presidency, even in North Carolina, a state that between 1873 and 1957 operated 23 so-called Jim Crow laws enforcing racial segregation. On the doorsteps, people avoided talking directly about race, although they regurgitated racist conspiracy theories that Obama might be a secret Muslim or lack a US birth certificate. They made no effort to cloak their hostility towards women in politics. ‘The gender stuff you could be explicit about. You could just be anti-women,’ Hannah says.

She stayed in Raleigh until the election and watched the count in a funeral parlour hired as campaign headquarters by the Democrats ‘because it was the cheapest thing on the block. The night of the election I passed out on the floor of the embalming room with a bottle of scotch. It was the absolute best feeling in the world.’ Back in the UK, she wanted to recapture that feeling and, more than that, find a way to open up politics to women. She successfully applied for a Kennedy scholarship, and spent a year at Harvard researching the topic she had pitched: the feasibility of a women’s equality party.

Five years later, back living in London and working for the Cabinet Office after stints helping the Labour Party to get more female candidates elected, she went with friends to the Women of the World Festival at the Southbank Centre, but all the events that interested her were sold out. ‘So we drank lots of wine and had this massive discussion. “WOW is great but this has to move into the political space. How do we do that and should we act on that?” It didn’t go anywhere and a couple of weeks later someone said to me “This party’s been set up”.’ Hannah laughs at the memory. ‘I was really cross and sulked.’

Her partner persuaded her to send an email offering to help out. She started volunteering, writing a strategy paper, and in October 2015 joined the Women’s Equality Party as Chief of Staff. ‘It was my dream job. The rest is history.’ She pauses. ‘Or not. In fact, it’s absolutely not history. It’s not even near to being history yet,’ she says.3

This chapter addresses a flurry of questions about women in politics – and about history. The United States rejected its first serious female candidate for the Presidency. What does this mean? Clinton had seemed poised to lead the charge of the 50-foot women. Instead history did that repeating-itself thing for which it’s renowned. Women have often made strides only to fall back. One lesson could not be more clear or more urgent: We must fight not only to extend gender equality but to retain those rights and protections we have.

The causes of her defeat bear more detailed unpicking. Clinton appeared part of the establishment, and in some ways she was. She had already occupied the White House, though never in her own right or on her own terms. Her story illustrates the limits of privilege-by-association and the sting in its tale. She earned her stripes, and some valid criticisms, during a career in politics spanning stints in the Senate and as Secretary of State, yet never escaped the accusation that she got where she did because of her husband. Her achievements were her own and so were her mistakes, but she was only ever permitted to own the latter. Her use of a private email server for government business was a bad misstep but in no way equivalent to the cascade of scandals and allegations surrounding Donald Trump.

During the Democratic primaries and in the main campaign, she accepted the mantle of the continuity candidate, the safe choice, the likely choice, enabling two white men, first Bernie Sanders, then Trump – the very definition of a fat cat – to present themselves as insurgents. This wasn’t just a tactical error on Clinton’s part. It reflected a profound misreading of the American people and of her own situation. Voters didn’t want continuity; they wanted change. She could have embodied that change. Certainly as a woman she was (excluding third-party candidates) the only real outsider in the race, for reasons already raised and explored here in greater detail.

She lost at least in part because she, and those around her, didn’t recognise the extent to which her gender was a disadvantage – and because many white female voters did not recognise the extent to which any privilege they enjoyed was circumscribed in the same ways. The result, the Trump presidency, is bad news for women everywhere. On his first full day in office, he signed an executive order blocking US funds to any organisation providing abortion advice or care overseas. What we cannot know is whether a Hillary Clinton presidency would have benefited women, other than by stopping Trump.

We cannot know, but we can draw conclusions, about Clinton and more widely about the impact of women in politics. The Women’s Equality Party argues that increasing the overall participation of women is necessary if women are to advance and to hold on to that progress. WE also maintain that such a change wouldn’t benefit only women, but everyone, by improving politics and the outcomes of the political system. What evidence underpins these arguments? If given a chance to head governments and fill half the seats in parliaments, might women run things not just differently but better? Does the answer depend on the individual women concerned, in the ways Crenshaw and Ensler highlighted in their reply to Steinem, or might this also be a numbers game, as Hannah’s vision of descriptive representation implies?

The next chapter tackles a huge question underlying this debate – whether what women are and how we behave is biologically hard-wired. First we’ll look at some of the Titans and at the rare examples of gender-balanced legislatures to make an assessment about the ways in which women are already shaping the future.

Let’s start with a reality check. When Theresa May took over from David Cameron, Money magazine got a little overexcited. ‘Even with all the uncertainty around the UK’s post-Brexit future, one thing is clear: Britain will soon be led by a woman, its first female prime minister since Margaret Thatcher left office in 1990,’ an article on its website declared. ‘Female heads of state have become common everywhere, it seems, but in the United States.’4

In reality, May added to a total of female world leaders – including elected heads of government, elected heads of state and women performing both roles – that for all their stature could still fit into a minibus. There are female leaders in Bangladesh, Chile, Croatia, Estonia, Germany, Liberia, Lithuania, Malta, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Namibia, Nepal, Norway, Poland, Serbia, Taiwan and the UK – that’s just 17 out of the world’s 144 full or partial democracies, or 18 if we include the estimable Nicola Sturgeon who heads Scotland’s devolved government.

Female leaders are less common globally than natural redheads are in Sturgeon’s own country; and redheads in Scotland, contrary to popular imagination, are not common at all, a flame-haired cohort amounting to around 13 per cent of the total population. Redheads and female leaders stand out, so we imagine their numbers to be much higher. Fifty-three democracies elect a president and a prime minister, and in all but nine of these nations, both roles are held by men. That means female leaders still comprise just 11.8 per cent of all world leaders, 12.5 per cent with Sturgeon.

The rarity of female leaders skews any gender ranking that includes female heads of state or government as a measure of equality. Consider the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report. The annual report seeks to judge the gulf between male and female citizens in each country surveyed by combining national performance scores attained in four categories: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. The health and survival category illustrates the wider danger of such rankings, taking into account just two sets of statistics: sex ratios at birth and healthy life expectancy. This provides useful information about divergent male and female health outcomes for diseases, but is a tool blunt to the point of inutility for assessing, for example, the level or impact of violence against women and girls. The last of the categories examines not only the make-ups of parliaments and governments but also ‘the ratio of women to men in terms of years in executive office (prime minister or president) for the last 50 years’. This helps to explain how in 2016 the Republic of Ireland strutted its stuff in sixth place, behind the Nordic countries and Rwanda, an unlikely feat that provoked eye-rolls among Irish women.5

When Mary Robinson became Ireland’s first female President in 1990, she saluted female voters ‘who instead of rocking the cradle, rocked the system’. Seven years later Ireland elected a second female President, Mary McAleese. She served until 2011. Both women used the platform to promote gender equality, but Irish Presidents have severely limited executive powers and instead deploy what McAleese termed ‘moral or pastoral’ influence. The Irish system did get something of a rocking, though, and not just because of the Marys. Before Ireland’s economic miracle proved a bubble, a wash of cheap money swept away some old features of the social and political landscape and lured back to the country a diaspora with expanded ambitions for women.

Even so, this shake-up was nowhere near fierce enough to fully dislodge the intertwined legacies of the Irish uprising and Catholicism. Revolutions often follow a pattern. The French Revolution and the Arab Spring both offered hope to the women who helped to instigate them, but swiftly abandoned any goals of female emancipation. Ireland’s revolution appeared to embrace the women who fought as equals alongside men, but went on to betray them. On Easter Monday 1916, rebel leader Patrick Pearse delivered a proclamation of independence on the steps of Dublin’s post office, promising ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens’, and making explicit that these rights included suffrage for women. This vision shimmered for six days only. British forces quelled the Rising and executed Pearse. The remaining independence leaders focused ever more narrowly on the goal of ditching British rule, and doled out an earthly reward to the clergy who supported their efforts, enshrining ‘the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church as the guardian of the Faith’ in Ireland’s 1937 constitution. As a result, Ireland didn’t permit divorce until 1995 and has yet to legalise abortion except when the mother’s life is in danger.

Ireland’s female Presidents represented not change but the desire for change. The fact of a female leader is no guarantee that women are thriving, and that means the gender rankings that count them are fallible. Nevertheless, treated with caution and stripped of congratulatory messaging about how well women are doing – which we really are not – rankings still provide a useful guide.

The Nordic countries always ride high, and deserve to do so, on the basis of measures such as female educational attainment and participation in the workforce. Their record of putting women into top offices is indeed noteworthy – by comparison to the exceptionally poor record in other parts of the world. Women have led Denmark and Finland – if only once – while Iceland has voted in, at different times, a female President and female Prime Minister. Erna Solberg, Norway’s current Prime Minister, is the nation’s second woman in the role.

The unlikely outlier is Sweden. This apparently egalitarian and liberally minded Scandi society has yet to elect a female premier. Stability – the goal of most governments and a marked feature of Sweden since it pulled itself out of the financial crisis that roiled the early 1990s – must share some of the blame. It feels good to live in a stable society if you inhabit a comfortable corner of that society, but stability can also function as a drag on progress. If political parties keep performing to expectation, they tend to stick with existing leaders and leadership formulae. It is only when things go wrong that people consider more radical change or that change simply forces its way through. This rule applies at national level too. Developing countries often prove more porous for women than long-established democracies, and a significant proportion of the countries that now have female presidents or premiers have experienced profound political and social upheavals in their recent pasts.

When crises loom, women sometimes climb. Brexit brought Theresa May to power. Michelle Bachelet became Chile’s first female President while memories of General Pinochet’s dictatorship were still raw. Park Geun-hye, South Korea’s first female President, won office after a spate of corruption scandals, dwindling growth rates and amid mounting tensions on the Korean Peninsula. The National Assembly voted to impeach her in December 2016 in the wake of a scandal centred on a close female friend alleged to have leveraged their relationship for personal gain. At the start of her trial on corruption charges in May 2017, the judge asked Park to state her occupation. ‘I don’t have any,’ she said. Her fall is now widely cited in South Korea as proof that women are unfit to lead.

The challenges facing any female leader when she reaches the summit are profound. Those who come to power amid turbulence, denied the protections of benign economic cycles and the diligent work of predecessors, struggling to control parties engaged in internecine warfare, are more vulnerable still. Sometimes the ink has not yet dried on their official stationery before the tumbrels arrive. This is the glass-cliff syndrome mentioned earlier.

In 11 countries, a woman led for less than a year. Female leaders in Austria, Ecuador and Madagascar broke records for the shortest tenure in top jobs, lasting just two days apiece. Canada may have a self-declared feminist at the helm in Justin Trudeau but the nation’s only female Prime Minister, Kim Campbell, managed just four months in office before losing a general election. ‘Gee,’ she deadpanned, ‘I’m glad I didn’t sell my car.’

The female leadership minibus lost a passenger in 2016, when Brazil defenestrated its first female president. Dilma Rousseff had taken over as the economy began to stall after a period of heady growth attributed to her male predecessor but reliant on buoyant Chinese demand and rising oil prices. Her impeachment for alleged financial irregularities and involvement in a bribery scandal linked to the state oil company Petrobras was not, as its architects claimed, the appropriate response of democratic politics to corruption. China’s slowdown and falling oil prices played a part. So did an inherent misogyny. Some of Dilma’s opponents agitated for her dismissal by producing stickers with her head superimposed on a different female body, legs akimbo and a hole where the crotch should be. Affixed to cars with the hole aligned to the petrol cap, they created the illusion that motorists filling their tanks were penetrating Dilma.

After her downfall, her critics waved signs that read ‘Tchau Querida’ – ‘Goodbye, Dear’. The price to Brazil certainly was. The charges against Dilma never included lining her own pockets; investigators alleged she had turned a blind eye to kickbacks at Petrobras and had disguised budget deficits. The same investigation suspected substantial bribe-taking among some of the politicians who engineered her expulsion.

Brazil’s legislature is 90 per cent male; around half of these men have themselves been indicted on corruption charges.6 One hundred per cent of the Cabinet assembled by Dilma’s white, male replacement, Michael Temer – himself accused of accepting bribes and of misuse of electoral funds – was white, a striking move in a country shaped by the diversity of its population. Brazil’s black and mixed-race nationals are in the majority, and also make up a lion’s share of the country’s poor. Temer’s Cabinet boasted another distinction: it was the first since 1979 not to include a single woman. ‘We tried to seek women but for reasons that we don’t need to bring up here, we discussed it and it was not possible,’ said Temer’s Chief of Staff, Eliseu Padilha.7 The new government quickly set about dismantling programmes designed to narrow Brazil’s overlapping wealth, race and gender gaps.

Some women manage to hold on, although holding on isn’t, of itself, a good thing. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf became Africa’s first female head of state when she triumphed in Liberia’s 2005 elections, two years after the end of a bloody civil war that killed more than 250,000 people and displaced nearly a third of the country’s population. She has declared she will not contest the presidential poll planned for October 2017. ‘Our people would not take it. And my age wouldn’t allow it. So that’s out of the question,’ she said.

Her decision – provided she remains true to it – distinguishes Johnson Sirleaf from a raft of male African leaders who cling to power long after any democratic mandate ebbs. The international community has already garlanded her with praise. In 2011 Johnson Sirleaf accepted a Nobel Peace Prize along with two other women, Leymah Gbowee, a fellow Liberian, also praised for helping to heal the country’s rifts, and a Yemeni human rights activist, Tawakkul Karman. A year later, Gbowee resigned as head of Liberia’s Peace and Reconciliation Commission, attacking Johnson Sirleaf ’s efforts to tackle poverty and criticising a record of nepotism that had seen three of the President’s sons take up senior positions at, respectively, Liberia’s state oil company, its National Security Agency and its Central Bank.8

Johnson Sirleaf may not after all represent quite the model of African leadership that the wealthy democracies of Europe and North America hope to see, but at least a few of the flaws of her leadership are rooted in the continent’s history of exploitation by some of those same countries. Liberia, founded by freed slaves, free-born black Americans and Afro-Caribbean émigrés, is the only African country never to have officially been a colony. (Ethiopia was briefly annexed by Italy in 1936.) What Liberia did not escape was Western imperialism. In 1926 the US tire and rubber company Firestone leased one million Liberian acres for 99 years at the annual rate of six cents per acre, inserting a clause that gave the corporation rights over any gold, diamonds, or other minerals discovered on the land, and also tying Liberia to a loan at punitive rates.

Africa’s oldest democracy, Botswana, has been holding elections only since 1966. Africa’s newest country, South Sudan, came into being in 2011. Colonisation – the patriarchal rule of the White Master – and the struggles for liberation that speeded its end continue to make their mark. Borders drawn with no respect to tribal claims, local history or practicalities exacerbate conflicts and encourage a tendency, reinforced by those conflicts, to try to consolidate power, whether along tribal or party lines or among families. With power comes wealth. ‘Politics is the avenue to the most fantastic wealth and so of course it’s been very competitive and the men want that space,’ says Ayisha Osori, a prominent journalist, lawyer and women’s rights advocate, who stood in the 2014 primary elections for Nigeria’s House of Representatives. ‘They want to keep that space for themselves and so women have to be equally as ruthless and as determined as the men.’9

The tangles of post-imperialism play out in the country Johnson Sirleaf governs and the ways in which she governs it, but her record also illustrates the point that Osori makes and that enthusiasts for increased female representation sometimes gloss over: female leadership isn’t necessarily free from the imperfections of the male variety.

The performance in office of another Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, reinforces that lesson. She would be Myanmar’s President if the military junta that kept her under house arrest for 15 years had not also drafted a constitution that excludes her from the highest office. Instead, Suu Kyi has become the nation’s leader in all but name, holding a dual role as State Counsellor and Minister of Foreign Affairs. An icon of peaceful resistance, her lustre is dimming as she fails to use her power to grant rights or recognition to the Rohingya, Myanmar’s marginalised Muslim population, or to curb human rights abuses by the army as it seeks to stem independence movements. When 50-foot women disappoint, they do so in a big way because our expectations of them are higher.

One name always crops up in discussions about what women bring to politics: Margaret Thatcher. Love her or loathe her – and the middle ground I occupy is noticeably underpopulated – she was one of the most successful politicians of the twentieth century. She won three successive general elections and left a party that, after ejecting her as leader for fear of electoral defeat, went on to win one more. She galvanised the UK and its moribund economy, at a cost that explains the enduring anger she still evokes, levied on traditional industry and every Briton on the sharp end of the history she was making. She speeded the end of the Cold War, recognising in Mikhail Gorbachev a different kind of Soviet leader. ‘I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together,’ she said. They did.

She showcased female potential. Yet her ghost is most often summoned to demonstrate that female leaders do not invariably promote female interests. ‘I owe nothing to women’s lib,’ she insisted, and during 11 years in office she made sure that women’s lib owed little directly to her. She rejected the idea that government should help mothers to return to work, telling the BBC she did not want Britain turned into ‘a crèche society’. She appointed only one woman to any of her Cabinets. Baroness Young held a minor portfolio as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster for two years, and came to the role with a sniggering nickname that spoke to the disquiet of men in Westminster and the media at seeing women rise: ‘Old Tin Knickers’.

Young’s boss inspired a more respectful variation on this theme, but one reflecting a similar unease about female power. ‘The Iron Lady’ lived up to the soubriquet, tempered to a steely obstinacy by years of fighting her way into rooms full of patronising, posh men, and then presiding at conference tables with more of the same. An essay by academic Rosabeth Moss Kanter, published in 1977, two years before Thatcher first entered Downing Street, foreshadowed Thatcher’s leadership style. Kanter, now a professor at Harvard Business School, observed that ‘tokens’, members of minority groups in organisations, are made to feel uncomfortable about their differences and so try to conform. That might mean acting like the majority, or fitting in with the majority’s expectations of minority behaviour. Such behavioural distortions only stop when minorities reach a critical mass.10 Subsequent studies suggested that mass is reached at 30 per cent and above, but more recent research points to a greater complexity in the number and habits of minority behaviour.

What is clear is that token women frequently try to fit in by behaving like men – or, in Thatcher’s case, by out-manning the men. A computer analysis of Hillary Clinton’s interview and speech transcripts discovered that her language became more masculine – a parameter defined by linguistics experts – as she moved from being First Lady and up the ranks of electoral politics.11 This transformation may have hindered rather than helped her. Women draw criticism and questions about their competence if they show emotion – a behaviour deemed feminine – yet any women who conduct themselves in ways judged masculine are punished too. Leaked emails written by former Secretary of State Colin Powell described Clinton as ‘a friend I respect’ but then went on to list supposed defects that included ‘a long track record’ and ‘unbridled ambition’. Researchers at Yale investigating differing voter reactions to male and female candidates found that voters felt ‘moral outrage’ against women who seek power because ‘power and power-seeking are central to the way masculinity is socially constructed and communality is central to the construction of femininity, [so] intentionally seeking power is broadly seen as anti-communal and inconsistent with the societal rules for women’s behaviour.’12 For many women in politics, this creates the catch-22 described by Ann Friedman in a piece about Clinton’s travails: ‘To succeed, she needs to be liked, but to be liked, she needs to temper her success.’

For Thatcher, downplaying her force of character or pretending to match any culturally generated ideals of femininity was never a serious option. Occasionally her advisers persuaded her to give interviews in which she awkwardly described a domesticity that was clearly inauthentic. She preferred to ignore her sex, but the men around her seemed unable to forget it. ‘She has the eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe,’ observed French President François Mitterrand, creepily. His successor Jacques Chirac whined about Thatcher during a confrontation at a summit: ‘What more does that housewife want from me? My balls on a plate?’

Veteran Conservative MP and former Cabinet minister Ken Clarke, forgetting he was wearing a microphone ahead of a TV interview with another former Cabinet minister, Malcolm Rifkind, voiced a milder version of this sentiment in a discussion of Theresa May that he did not intend for broadcast. ‘Theresa is a bloody difficult woman,’ he said. Clarke’s thought train continued to its obvious conclusion: ‘But you and I worked for Margaret Thatcher.’ Britain’s first female Prime Minister is the model by which the second female Prime Minister, and all other female leaders, continue to be judged.

Facile though these comparisons are, female leaders, as a class, tend to resemble Thatcher in one respect. There is less show-offery. Women more often appear to thrive on the exercise of power than the attendant publicity. Think how Angela Merkel compares to Nicolas Sarkozy and Silvio Berlusconi, or Theresa May to her one-time leadership rival Boris Johnson, or Hillary to Bill or Donald. Thatcher never sought press coverage for its own sake.

There is a commonality between Thatcher and Merkel that is also worthy of mention: a background in science. When Thatcher entered politics, she forged a new path. The elite of society imbued their sons with the expectation of leadership, and trades unions provided an alternative training ground for political talent. Family ties delivered the world’s first female Prime Minister, Sri Lanka’s Sirimavo Bandaranaike, to power and installed the world’s longest-serving female leader, India’s Indira Gandhi, in office. Political dynasties produced Aung San Suu Kyi, Sheikh Hasina, her predecessor Khaleda Zia, Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto, Indonesia’s Megawati Sukarnoputri, Argentinian Presidents Isabel Martínez de Perón and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Cory Aquino of the Philippines, and South Korea’s Park Geun-hye. Thatcher had no such advantages. She studied chemistry and went on to work in the field at the food manufacturer Lyons (where, legend has it, she helped to invent soft-scoop ice cream).

Angela Merkel found a calm berth in East Germany as a researcher in physical chemistry. These parallels are noteworthy because the duo also gained a reputation for the kind of evidence-based decision-making more routinely associated with laboratories than parliaments. Even so, Thatcher and Merkel will be remembered for big, bold projects rooted in ideology and emotion rather than cold calculation. Thatcherism held, at its core, an instinctive and visceral moral certitude that branded opposing ideologies as not just wrong but malign. Merkel’s pivot from cautious consensus-builder to passionate advocate of European engagement in solving the refugee crisis drew deep on her own experience. She too had been the wrong side of the barbed wire.

Germany’s 2005 elections ended in deadlock. Neither Merkel’s centre-right Christian Democrats nor Gerhard Schröder’s left-leaning Social Democrats, could muster a workable majority. Merkel consulted, forged alliances, held her nerve until Schröder withdrew, leaving her to head a grand coalition. She was not only the first woman to occupy the Chancellery, but the first leader of reunited Germany raised behind the Iron Curtain. As TIME scrambled late at night to produce a cover story, international editor Michael Elliott composed a headline that almost went to print before we noticed its double meaning: ‘Not Many Like Her’.

There still aren’t many – if any – like her, and these days you’d be forgiven for assuming that not many of her colleagues or compatriots like her either. Four successive state elections in 2016 saw the Christian Democrats lose votes, primarily to the hard-right Alternative für Deutschland. The AfD started as a protest party campaigning against German commitments to bail out floundering Eurozone countries, but found fresh purpose on 4 September 2015, when Merkel responded to the press of refugees from Syria stranded in Hungary by opening the border and issuing a welcome. ‘Wir schaffen das’, she said: we will manage.13 At first most Germans agreed, but since more than a million refugees and migrants sought to make new lives in Germany, that consensus has melted.

Mass assaults on women in Cologne during the final hours of 2015 tested German hospitality. There is still little clarity about the nature of these attacks: to what extent these were planned and whether most perpetrators were, as initially reported, foreigners. The authorities continue to pursue prosecutions but have admitted they do not expect to identify the majority of those responsible. If they did, bringing them to justice would be difficult. Germany’s antiquated laws on sexual assault put the burden on women to show they had physically resisted their attackers.

A narrative about Merkel gained traction inside the country and out: she was a busted flush. Germany’s first female Chancellor had broken Germany and, far from helping German womenfolk, had exposed them to danger.

Pretty much everything about that narrative was wrong, although Merkel did make one key miscalculation. Until the refugee crisis, the criticism routinely levelled against her was that she used her power too sparingly – that she had responded too slowly to the Eurozone crisis and with too much focus on German national interests at the expense of poorer countries such as Greece. She put a different gloss on her approach: she preferred to govern in ‘many small steps’, rather than big ones.14 This fitted with the legacy of her early life, in a police state where she learned to achieve without attracting attention. It was also pragmatic: the German voting system creates coalitions rather than outright majorities, and deploys multiple checks and balances. German history warns against unfettered power. Even so, Merkel confronted the migrant crisis as Europe’s strongest leader, the only one with political capital. In finally spending that capital, she sought to instill in other European leaders a sense of collective responsibility. This was, as she saw it, ‘a historic test of globalisation’.

Merkel alone rose to it. She had overestimated Europe’s capacity for solidarity. Her remarks at a press conference after her party’s poor showing in the September 2016 Berlin state elections, widely misreported as a mea culpa, instead restated her convictions. She did regret the phrase ‘we will manage’, which ‘makes many people feel provoked, though I meant it to be inspiring’.

However, she had followed a humanitarian imperative and a strategy that, despite flaws, had started to bear fruit. Signs of progress did nothing to quiet her critics, especially within the ranks of her Christian Democrats and their Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU). They had never really accepted her; now, with federal elections due in September 2017, they began to treat her as a liability. Her approval ratings did drop, from 67 per cent in September 2015 – an astonishingly lofty figure for a politician in her third term of office – but have risen again to only a few points shy of that level. Her popularity is international. When I posted the news on Twitter that she had decided to run for a fourth term, my timeline filled with ‘phews’ and ‘thank gods’ and ‘thank fuck: we need an adult’.

In Germany, female voters are more likely than men to vote for left-of-centre parties. This pattern repeats in many parts of the world, including the US, where the majority of white women who voted for Trump was not as large as the majority of white men who backed him. You can see why that might be. Conservatism is inherently disposed towards maintaining the status quo, and some groups of female voters know this is not to their benefit, not least because of the right’s fondness for downsizing the state at the potential costs of state-sector jobs that employ women and services that support women, plus a tolerance for a wide income spread in a system that relegates more women to the lower tiers. Merkel bucks this trend by appealing across party lines to Social Democrat voters – and to women. At the last election, 44 per cent of all female voters backed Merkel’s party, compared to 24 per cent for the Social Democrats.

She has done so in part by being a woman and showing what women can be in a country that until relatively recently in its dominant Western states envisaged only three spheres of female activity: Kinder, Küche, Kirche – children, kitchen, church. Up until 1958, a West German husband could demand his wife’s employer sack her if she neglected the housework. These attitudes were still reflected in the education system Merkel inherited, in which a majority of schools in the west ended at midday so pupils could return home for a cooked lunch. When Merkel first led the Christian Democrats into an election, opponents and colleagues alike asked ‘Kann die das?’ Is she able to do this? ‘With a negative touch,’ says Ursula von der Leyen, Germany’s first female Defence Minister. ‘Nobody is asking any more.’

This does not mean Merkel’s record on promoting gender equality is perfect. Like many female leaders, her instinct has been to shy away from gender politics. She was uncomfortable with her first portfolio in Helmut Kohl’s government, as Minister of Women and Youth. Germany’s sluggish birth rate rather than any feminist impulse prompted Merkel to introduce a wide range of measures to support working mothers, including the provision of parental leave paid up to 65 per cent of salaries for up to 14 months, guaranteed daycare for children aged one or above, and an expansion of all-day schools.15 She only reluctantly gave in to deploying quotas to increase female representation on the boards of large German companies. ‘It is pathetic that in more than 65 years of the Federal Republic of Germany, it was not possible for the Dax-30 companies to get a few more women on supervisory boards on a voluntary basis,’ she said. ‘But at some point there had been so many hollow promises that it was clear – this isn’t working.’

German society has witnessed significant changes. Female participation in the German labour force rose by two percentage points in the decade ahead of Merkel’s election and by eight points during her first ten years in government. It would be unwise to claim a direct correlation; many factors will have played a part. Nevertheless, there’s no denying that German women have risen under Germany’s first female leader.

Theresa May’s elevation prompted crowing in Tory ranks. The Conservatives had notched up a second female Prime Minister before Labour even managed a female party leader. May, Merkel and three other female leaders in Europe, Norway’s Erna Solberg, Serbia’s Ana Brnabić and Poland’s Beata Szydło (and Szydło’s immediate predecessor Ewa Kopacz) are all on the right. Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović belonged to the conservative Croatian Democratic Union party before her election as Croatia’s President. This does not mean rightwing politics promotes better outcomes for women, rather that parties of the left are especially bad at promoting women.

The paradoxical explanation for this phenomenon is that parties of the left have historically championed gender equality. This means they are often too convinced of their own virtue to recognise their failings. Those failings loosely group into two categories. The first is one of precedence. In their desire to solve all structural inequalities, these parties get caught up in unhelpful binaries of the kind that disfigured the Democratic primaries in 2008 – ethnic minorities or women, class or gender, pensioners or underprivileged youth – reflexively assigning the lowest priority to women even though most forms of disadvantage intersect with being female. Far-left activists aim not to fix parts of the system, but to change the whole system, again stranding women in an endless waiting game. They also mistake optics for action. Amnesty International’s 2015 report on Bolivia noted that the socialist government had set up a Gender Office and Unit for Depatriarchalisation and created a Deputy Minister for Equal Opportunities within the Ministry of Justice and Fundamental Rights, responsible for the advancement of women. However, none of these new institutions had been allocated the resources necessary to be effective. The Equal Opportunities brief, for example, received just 5.3 per cent of the ministerial budget.16 As the White Queen tells Alice, ‘The rule is jam tomorrow and jam yesterday – but never jam today.’

The second category and reason for the ongoing failure to promote women sometimes still dares to speak its name in parties and organisations of the right: hostility towards women. In choosing to fight Conservative MP Philip Davies in the snap election, we highlighted a particularly flamboyant example of this. Davies joined Parliament’s cross-party Women and Equalities Committee and immediately proposed dropping the word ‘women’ from its title. He tried unsuccessfully to derail a bill to ratify the Istanbul Convention, an international accord to tackle violence against women, by filibustering in the hope that the bill would run out of time. On another occasion he gave a speech that inadvertently boosted sales of baked goods. ‘In this day and age the feminist zealots really do want women to have their cake and eat it,’ he declared. Women responded by posting photographs of themselves munching cake.17

The left likes to imagine that it is exempt from such wrongheadedness. In reality, misogyny flourishes like knotweed, undermining foundations of parity and respect and periodically breaking into the open, rampant and destructive. The online abuse directed against female MPs who disagree with Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership has been different in degree and content to anything experienced by male dissidents. The invective may not emanate exclusively from the MPs’ left-wing opponents, but could less easily survive in a culture that made serious efforts to stamp out such abuse.

Labour is by no means the only offender. Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination unleashed toxic attacks on Hillary Clinton, not by Sanders but by a rump of his followers, so-called Bernie Bros. Two British hard-left parties, the Workers’ Revolutionary Party and the Socialist Workers’ Party, both failed to curb sexual violence in their own ranks. The WRP disbanded after revelations that its leader Gerry Healy had sexually abused female members. The SWP responded to a rape allegation against a senior figure in the organisation by holding a kangaroo court that interrogated the complainant. Had she been drunk? Had she definitely said no?18

George Galloway, a former MP who set up the Respect Party after his expulsion from Labour, dismissed rape charges brought in Sweden against Julian Assange. The WikiLeaks founder was guilty, said Galloway, of ‘personal sexual behaviour [that] is sordid, disgusting, and I condemn it’. This was, however, merely ‘bad sexual etiquette’. ‘Not everybody needs to be asked prior to each insertion,’ Galloway added.19 In 2016, he campaigned to be Mayor of London. The Women’s Equality Party fielded a mayoral candidate at the same elections, party leader Sophie, together with a London-wide slate of candidates. WE attracted 343,547 votes – a 5.2 per cent vote share and a magnificent result for a first election. (The Green Party’s first electoral outing, at the October 1974 general election, claimed just 0.01 per cent of the vote.) The cherry on our feminist zealots’ cake was Sophie’s performance against Galloway. He started with an advantage as a public figure, a political veteran and one-time star of reality TV show Celebrity Big Brother; he had also presented shows for Iran-backed Press TV and the Russian-funded RT network. Sophie had come to politics as WE’s first leader, just ten months before election day. She outpolled him by almost 100,000 votes.

We celebrated Galloway’s defeat but there was nothing to cheer in the weakness of the British left. Labour performed better than expected in the 2017 snap election, buoyed by an increased youth vote for Jeremy Corbyn and a miserable campaign by the Tories, but still chalked up a third successive loss. The Conservative minority government, reliant on the votes of the socially conservative Northern Irish DUP, continue to tack further to the right.

This bodes ill for women, if not entirely for the reasons set out by traditional left-wing analyses. From the outset, Sandi and I conceived of the Women’s Equality Party as non-partisan. We did so not just because of the serial failures of the left to match deeds to words. Three-quarters of British voters identify themselves as centrists or to the right of centre. We need a chunk of those votes to make change. We want to reach Equalia. We want jam today.

A good starting point is to test a common assumption about women in politics: that women are pragmatic and collaborate across party lines. Academic research supports this view. Analysis of the progress of bills proposed in the US House of Representatives between 1973 and 2008 showed that women in minority parties did better than their male colleagues at keeping their bills alive because they were more adept at garnering support across the aisle.20 (The US Senate demonstrated another female strength in January 2016. After a blizzard in Washington DC, women showed up for work. No men slogged through the snow. ‘As we convene this morning, you look around the chamber, the presiding officer is female. All of our parliamentarians are female. Our floor managers are female. All of our pages are female,’ said Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski. ‘Perhaps it speaks to the hardiness of women.’)

My own experience of covering politics encouraged me to believe women might be less inclined to party tribalism. I had seen Westminster women from different parties not only forming alliances in recognition of common goals, but bonding and swapping tips about how to avoid being slapped down or touched up.

Women are diverse but there is always a reservoir of shared experience. The more privileged among us may never truly understand the harsh realities of being doubly or triply disadvantaged by the intersections of race or age or sexuality or gender identity or disability or poverty. We occupy different positions in the kyriarchy – a word coined to describe these intersections and acknowledge the ways in which they enable women to oppress other women – but all of us have found ourselves on the receiving end of the patriarchy. Women of the right may not recognise either expression and are more likely to believe patriarchal structures should be reformed rather than eradicated, but they can be seriously effective in bringing about such reforms as Angela Merkel has shown. Moreover, the impulses of the right increasingly align behind the promotion of women, as the market increasingly recognises the value of women. The later chapter on business explains why that is – and why that recognition isn’t yet matched by equal representation in boardrooms or equal pay at any level.

May’s own record on gender equality was at best a curate’s egg even before her alliance with the DUP. A first tasty morsel came in 2005 with her co-founding of Women2Win, an organisation dedicated to increasing female representation on the Conservative benches. As Home Secretary she introduced new powers to curb domestic abuse, in particular in cases of coercive and controlling behaviour, and then chivvied the police to use these powers. By contrast, her handling of Yarl’s Wood, a detention centre holding women and children pending immigration hearings, was truly rotten. She extended the contract with the private company Serco that runs the facility, despite allegations of sexual violence and other abuses towards its inmates by Serco staff.21

Once she became leader, the Conservatives continued to pull further to the right. This probably helped win votes back from UKIP, which was anyway flailing. In entering into a so-called confidence-and-supply arrangement with the DUP, she aligned herself with a party with a history of opposing abortion and LGBT rights.

Regressive social conservatives don’t just try to block progress. They often invoke a future that turns the clocks back: to an age of safety and certainty and homogeneity; to faith in strong leaders who take care of the big stuff.

Such worlds have, of course, never existed, but that makes their pull more potent – and more dangerous. Worlds-that-never-were operate according to laws-that-never-work. Parties of the hard right identify real problems – the competition for scant resources, the democratic deficits created by globalisation, and religious extremism and misogyny dressed up as ‘cultural practice’ – but proposes responses that will make everything worse: xenophobia and a retreat into isolation. Often the nostalgia invokes a natural order threatened by the forces of social change – and that supposed natural order never turns out well for women. Beata Szydło’s Law and Justice Party in Poland has cut state funding for IVF treatment, tightened the availability of contraception and only backed away from a total ban on abortion, even in cases of rape, after mass protests. Some hard rightists allow themselves to imagine that a lack of contraception or access to abortion will encourage young couples to marry. Some hard rightists seem to believe that hostility towards homosexuality will make it go away.

The hard right also routinely mistakes feminism for the cause of bad relations between the sexes, rather than recognising feminism as a response and solution to the conflict. Even so, parties of the hard right are often led by women. Frauke Petry – like Merkel, a former chemist who grew up in East Germany – led Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland to its biggest successes, entry into five state parliaments in 2016 and in Saschen-Anhalt an astonishing 24.3% of the vote. Pia Kjærsgaard, co-founder and former leader of the Danish People’s Party, moved on to become the Speaker of Denmark’s Parliament and a prominent critic of multiculturalism. Siv Jensen has brought Norway’s Progress Party into government for the first time, in coalition with Erna Solberg’s Conservatives. Jensen, who serves as Finance Minister, has moderated her anti-Islam rhetoric since taking office but opposes her own coalition’s agreement to expand the numbers of Syrian refugees it accepts.

That women rise in such parties is a reflection of the fractious nature of such groups – remember: crises create room for movement – but the hard right has also got wise to the way a female face can lend an air of friendly modernity to their movements. They draw inspiration from a prominent role model. In 2011 Marine Le Pen took control of France’s Front National from its founder, her father Jean-Marie, and four years later oversaw his expulsion from the party after he downplayed the Holocaust as ‘a detail of history’. Under her stewardship the party has flourished, successfully expanding its reach to voters who shied away from its original incarnation. Her slicker, friendlier Front National sublimates its racism into messaging linking immigration to Islamism and an increased threat of terrorism. Regional elections in 2015 saw it come first in the opening round of voting with 28 per cent. She and her niece Marion Maréchal-Le Pen both won more than 40 per cent in their contests. For a time, it looked as if Le Pen might beat that score in her 2017 race for the Élysée Palace. She trounced traditional conservatives and old-style leftists in the first round, but lost out in the second to the only candidate who could also present himself as a political outsider, Emmanuel Macron, leader of En Marche!, a party he’d founded only a year earlier.

Le Pen reinforces the warning against expecting of female leaders a more compassionate politics. Yet she also illustrates strong arguments for prising open political clubs to admit more women. For one thing, traditional politics has been weakened precisely because it operates clubs. If mainstream parties had kept closer touch with voters, they might have done a better job of answering the real concerns of those voters. Instead they’ve created space for demagogues to masquerade as truth-tellers and champions of the working man (if more rarely of the working woman).