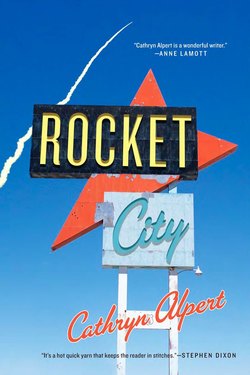

Читать книгу Rocket City - Cathryn Alpert - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ALAMOGORDO

ОглавлениеThree melons and a dwarf sat in the front seat of Marilee's '72 Dodge, but the cop was not amused. "I'd get rid of that bumper sticker if I was you," he said. " Folks 'round here, they're proud of their history." Marilee's bumper sticker said, "One nuclear bomb can ruin your whole day." Wrong place, wrong time. This spot on the road crossing White Sands Missile Range was fifty miles southwest of Alamogordo.

"You two traveling together?" the cop asked.

"Might say," said Enoch.

The cop's lips drew together like a drawstring purse. It was midnight and he wore sunglasses. "I'd like to see your license," he said, shining his flashlight at the little man riding shotgun.

"No can do."

"You have any I.D.?"

"Nope."

"What's your name?"

"Enoch Swann."

"Where you from?"

"Des Moines."

The cop gave Enoch a hard look. Enoch stared back at the cop. Marilee dug her fingernail into a tear in the upholstery. Surely it was not against the law to share the front seat of a woman's car with two honeydews and a casaba.

"Those melons come with you from California?" the cop asked Marilee.

"Near Bowie. Little road stand," said Enoch.

Marilee's body stiffened. The cop had to know Enoch was lying. There'd been nothing near Bowie— no road stand, and certainly not at night. Marilee wondered if they could be arrested for lying about fruit.

"Step out of the car," the cop ordered.

Enoch opened his door and lurched toward the rear of the automobile.

"You too, miss. Both of you stand over there," he said, aiming his flashlight into the space between the cars' bumpers.

Marilee did as she was asked, telling herself that none of this was happening.

"Put your hands on the trunk, spread your legs, and lean over. I'm going to search you."

The cop searched Enoch, then Marilee, patting them down from shoulders to feet. The patrol car's headlights shone up between their legs as they stood spread-eagled against the trunk of the Dart. "I'm going to search your car now."

For what? she wanted to ask him. On what grounds? For speeding? Was any of this legal? The cop climbed inside her car. "Is he going to find anything?" she whispered to Enoch.

"I'm not psychic."

"You shouldn't have said we bought the melons in Bowie. Don't you know it's against the law to take fruit across state borders? That's why they ask you about fruit. You lied. You told him we bought it here in New Mexico."

"Bowie's in Arizona. If he knew his geography, he still could've nailed you. But he doesn't know jack. Look at him. He's an asshole."

The cop sat in the backseat of the Dodge, rifling through the contents of Marilee's purse. He flipped open her compact, ran his finger over the powder, sniffed, then tasted it.

"What's he doing?" she asked. "Couple of lines," said Enoch.

What was it that had compelled her that afternoon to go back for the dwarf ? Her mother had taught her never to pick up hitchhikers, a lesson she hadn't needed to learn. Always shy, she'd never had the inclination to extend herself to strangers, especially to someone as different as Enoch. Perhaps it was the look on his face as she drove by him the first time, a look that said he'd been standing out on the road since dawn and hers was the first car that had slowed. Or perhaps it was the way he pulled his thumb in when he saw she was a woman alone. Or maybe it was nothing more than his obvious helplessness. Where he stood, alongside the interstate between Aztec and Sentinel, was nowhere; he'd been abandoned in the middle of the Arizona desert. As she passed him, the late-September sun reflected up off the asphalt so that his face seemed lit from all angles, open, devoid of shadow and threat. How dangerous, she asked herself, could a dwarf on crutches be?

At the first rest stop, Marilee turned the car around and drove west, back toward where she had seen the dwarf. She passed him again, on the other side of the highway. The dwarf followed her with his eyes. It would be crazy to pick him up, she knew, but now she felt obligated since he'd seen her drive by twice. She couldn't pass him a third time.

Marilee crossed over the unpaved median and again headed east. She slowed as she approached him, tensing at the crunch of pebbles under her tires. Closer now, she studied his features. He was a clean dwarf. His brown hair was tidy; his face, newly shaven. He stood about four feet tall and carried a backpack. He wore cowboy boots, a red shirt, and jeans.

Marilee reached over to open the door as he hobbled toward her car. He tossed his backpack and both crutches into the backseat. They landed on her suitcase with a thud.

"Obliged," he said in a normal voice as she pulled back into the slow lane. Was it just midgets who sounded like Munchkins?

"Been out here long?" she asked.

"Not too."

So, she hadn't saved him from near death. No matter. She liked his voice and she liked his face: a cleft chin and a nose cocked slightly to one side. His skin was tanned; his teeth clean; and when he raised his sunglasses to rub his eyes, she saw a glint of intelligence.

"I'm Marilee."

"Enoch," he said, holding out his hand. She shook his fingers. They felt like a handful of Vienna sausages.

"Enoch's an unusual name." How typical, she thought. Dwarfs always have oddball names, like Eylif or Egan. Or Bror. A band of motorcyclists passed them in the oncoming lane. Enoch squirmed and put his feet up on the dashboard; his stubby legs extended fully. Marilee fixed her eyes on the road and pretended not to have noticed, determined neither to stare nor to appear intrigued. "So," she asked, "where you headed?"

"Same place you are."

She didn't like the way he said that. It sounded ominous, as if he saw their destinies about to overlap.

"Where are you from?"

"Kingfield. Kingfield, Arizona. Couple hundred miles north. Big fire a few years back. That's when I split."

"Where you living now?"

"Here and there. In the desert."

Great, she thought. A weirdo.

"Take some melons," her mother had insisted, heaving three of them at her at once. "So in case the car breaks down, you'll have something to drink." It would never occur to her mother to send something direct, like a thermos. "And take this knife, too," she'd said. "You never know when you might need it." The kitchen knife lay hidden in the glove compartment of her car. Marilee wondered if she'd have the guts to use it, if neces sary, and whether she'd be able to reach for it in time. Enoch shifted in the seat next to her. The honeydews rolled toward his thigh.

"My mother's idea," said Marilee, gathering the melons back into the space between them on the seat. "So if the car breaks down, I won't die of thirst. My mother's kind of out there sometimes. Of course, if anything happened, I could always drink radiator water. I brought a knife, too, so if I had to, I could hack up a cactus."

"Or a camel," said Enoch.

Definitely weird.

"So, where are we off to?" he asked. Again, her insides jumped. The highway stretched before them, a colorless slab dissolving into a blurred horizon. Save for the sun, the sky was bare. No clouds floated by. No birds flew. In other cars, people looked half-sedated, as though hypnotized by the strobe of disappearing broken lines and the hum of tires on asphalt, the white noise of the open road. Marilee was glad to have gotten it in about the knife.

"Alamogordo," she replied. "To get married, but he doesn't know that yet. Well, he does and he doesn't. I mean, he asked me to marry him, but he doesn't know I'm on my way." Oh God, she thought, she shouldn't have told him that.

"Roll it down?" Enoch pointed to the window.

"Sure. It sticks sometimes. You have to really crank it."

The dwarf turned the handle, but the window didn't stick. He then stood on the seat and reached for his backpack on top of her suitcase. What was he reaching for? A knife? A gun? Why in God's name had she picked him up?

A small bag of granola materialized from his backpack's zippered pocket. "Have some," he offered.

Marilee considered her options. What if it were drugged? Was he going to eat some too? She took a small handful. It tasted like a clump of dried weeds.

"What's his name?" asked Enoch.

"Who?"

"Mr. Wonderful."

"Oh, Larry. He's this guy I've been going with a long time. Since high school, really. Funny how you can end up with someone you knew back in high school. I mean, I don't know anyone I knew back in high school. Except him, of course." She was babbling.

"Larry what?"

Why did he want to know? " Larry Mitchell," she said, plugging in the first surname that came to mind.

"Boring," said Enoch. " Larry Mitchell. Mr. and Mrs. Larry Mitchell. Dull as dust."

Marilee studied the stretch of desert around her. Cactus. Tumbleweeds. Dirt for miles. A few rocks, not many. Probably insects under the rocks.

"What's he do, this guy, Larry?" Enoch offered her another handful of granola, but she declined.

"He's in the military. Holloman Air Force Base."

"Does he fly jets?"

"He's a flight instructor."

"So," said Enoch, "you're going to roll into Alamogordo so you two can get hitched?"

"That's right."

"And he has no idea you're on your way?"

Heat rose off the pavement and warped vision, not unlike the aura of an impending migraine. "Well, he does, sort of. I mean he expects me. Soon. But he doesn't know when, exactly. I was going to be a surprise."

"Sort of, 'Here I am. Let's find a church,' " said Enoch.

"Sort of."

"Sort of, 'Hi, I'm moving in. Hope you don't mind.' "

"No. Not like that at all. He's going to love it when I show up. He's been wanting this for a long time."

"And you?"

"I want it," she said. "I've thought about it. It makes sense that we get married."

"Why?"

"Look, are you hungry? I'm starving. I get cranky when I don't eat. What's the next town?"

"Casa Grande."

"Let's look for a restaurant."

"Yo! Casa Grande!" Enoch shouted, raising his fist in a power salute and stomping his feet on the dashboard. A toothbrush fell out of his pants cuff.

He was definitely one weird dwarf.

"Let 's play a game," said Enoch, as soon as they'd ordered. "I'll ask you a question, then you ask me one. Whoever loses pays."

"Okay," said Marilee, although she was not sure at all that it would be okay.

"Can an irresistible force encounter an immovable object?"

"Sure." She was glad his question had been nothing personal.

"Which one gives?"

Marilee thought about it for a moment. "Well, it's really just a matter of semantics."

"Not at all," said Enoch. Two middle-aged ladies in the next booth eyed them with curiosity. Enoch's chest was level with the edge of the table; Marilee was glad the waitress hadn't offered him a booster seat.

"Okay," she said. "I guess it's impossible to answer."

"Bingo. One to nothing. Your turn."

Marilee took her time thinking of a question. She turned down the corners of her paper place mat. She traced her spoon over the outline of a hobo eating pancakes. He looked a little like Enoch. Sipping coffee, she stared out the window at the filling station next door. The attendant scratched himself when he must have thought no one was looking.

"All right, I've got one. Which came first, the chicken or the egg?"

"Impossible to know," said Enoch. "And a cliché."

" Think again." Two could play this game.

A group of teenagers erupted in laughter from across the room. They sneaked occasional glances at Enoch.

"Impossible," he said again.

"The egg," said Marilee. "It's obvious. At some point there had to be a mutation. But by the time the egg is formed, it has all its genetic material intact. It's a potential chicken. So the responsible gene, the gene that made the critical difference, had to have mutated inside the hen before it became part of the fertilized egg. And something had to pass on that altered gene. Something that was not quite a chicken but gave rise to a mutant egg that was destined to become the world's first chicken."

Enoch's face brightened. "Yes, that's logical. Very good." Their waitress appeared with their dinners. She wore a red ruffled skirt and an embroidered hat that said, "Doreen."

"I've got another."

"My turn," said Enoch, dipping a french fry in the Thousand Island dressing that ran out the side of his Hoboburger. "If God is all powerful, can he build an object too heavy for him to move?"

"Another paradox."

"Are you certain?"

"Positive."

"I win," said Enoch. "If God is all powerful, he can transcend paradox."

"What makes you so certain God's a he?"

"Different question. Stick to the point."

Marilee thought about the point. "Interesting," she said, forcing a smile; secretly, she was pissed. "Now it's my turn. A man is walking down a road. In order to take a step, he must first travel half that distance. A half-step. Then, in order to take a half-step, he must first travel a distance half the length of that. Will he ever reach his destination?" She bit into her club sandwich and hit a toothpick.

"Zeno's paradox. The answer is no."

"Wrong," said Marilee, with her mouth full. "Faulty premise. People don't move in half-steps, do they?"

"Then again, some people don't move at all."

What was that supposed to mean? She pinched a blister from the end of her bacon and buried it under her carrot twist. "All right. How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?"

"Box-step or hora?" said Enoch.

They ate the rest of their meal in silence. When Doreen brought their check, they agreed to split it. Marilee took the money to the cashier while Enoch went in search of a bathroom. She'd gone earlier, while the hostess was seating Enoch, because she didn't want to be seen walking through the restaurant with a dwarf.

Marilee paid the bill and sat on the brown vinyl seat by the coffee shop's front door. Five minutes passed. Then ten. What was he doing in there? she wondered, then asked herself if she really wanted to know. And why, come to think of it, was she sitting there waiting? This was her chance. She'd never have to see him again.

Her keys jangled as she made her way swiftly through the parking lot. But as soon as she opened the car door, she saw that Enoch had left his backpack. Now what? She could leave it on the ground, but what if somebody stole it? No, she'd have to take it into the restaurant and leave it for him there. She started the engine and steered the Dart toward the entrance. As she pulled up, an elderly woman held the door open for Enoch.

"That's nice," he said, resuming his seat next to the melons. "Bringing the car around. Thanks."

"Sure," said Marilee. She knew what it felt like to steal from an invalid. Strike a child. Throw a kitten off a bridge.

" So," said Enoch, as soon as they were back on the highway. "What does this Larry guy do for kicks?"

Not again, thought Marilee. "Well, mainly he likes to jog, work out with weights, that sort of thing. He's into fitness. Poetry. Books about the Civil War."

"That's it?"

"Sometimes he has friends over and they rent movies."

"Porno flicks?"

"Oh, God no, he'd die." Marilee laughed. "I bet he's never even seen one."

"Have you?"

She looked over at the little man in her front seat cleaning his fingernails with the corner of a Hobo matchbook.

"So show me this guy," he said. "A picture. I want to see."

She rooted in her purse for her wallet, wondering at the same time if this were a good idea. Couldn't he just grab it out of her hand? That's silly, she thought. Where would he go? She opened her wallet with one hand and dug out a photo of a young man in camouflage fatigues. She handed it to Enoch. The man in the picture had blond hair and a weak chin. The badge over his pocket said, "Johnston."

Enoch tossed the photo faceup on the dashboard. "So, you and Larry planning to have kids?"

"Why do you keep asking me about Larry?"

"Fine. Let's talk about me."

Marilee wondered what she should ask him. She wanted to ask what it was like to be a dwarf, but the words stuck in her throat. "Okay. Tell me about the fire. In Kingston."

"Kingfield," said Enoch. "Another time." A bug spattered against the windshield and left a yellow-green smear like the feathered tail of a comet. "I've got one," he said. "If a tree falls in the forest and nobody's there to hear it, does it make a sound?"

"Talk about clichés."

"Yes, but does it?"

"It's a moot question. Without a witness, there's no way to know."

"I think it does," said Enoch.

" Based on what?"

"Track record. All trees that have ever fallen in the presence of people who can hear have made a sound. That means something."

"But one that falls in a deserted forest might fall silently. You can't prove that it doesn't. That's not logic."

"Then you rely on faith."

"What's faith got to do with it?"

"Where logic fails," said Enoch, "that's where faith steps in. Sometimes that's all you've got. You've got to have faith in the laws of physics and you've got to have faith in people. Remember that line?" he asked, turning to face her across the front seat. "At the end of Manhattan, remember? Mariel Hemingway says that to Woody Allen. 'You gotta have a little faith in people.' Great line. Sums up the whole movie."

They continued east on Interstate 10, through Tucson, past Benson and Willcox. The sign at the border said, "Welcome to New Mexico. Land of Enhancement." Enoch curled up beside the melons and fell asleep as darkness consumed the landscape. He slept through Marilee's stop for gas in Lordsburg. He slept through the convoy of trucks that rumbled past them just east of Las Cruces. When he awoke, hours later, they were near White Sands Missile Range. Red and blue lights flashed in the rearview mirror.

Enoch stretched his legs and bolted upright. What he said startled her. He said, "You're a woman and I'm a dwarf. Woody is neither. I've got to pee."

The cop crawled out of the backseat of Marilee's car. "We got a speed limit here, miss," he said. "Try and stay under it." He tore the ticket from his pad and handed it to her with a smile. "Thanks," said Marilee. "For what?" asked Enoch. As the cop drove west, Enoch went in search of a bush. He didn't use his crutches, and he wobbled as he walked. Marilee leaned against her front

fender and stared off into the distant lights of Alamogordo. She hated getting tickets, hated cops almost as much as she hated herself for having been so accommodating. She tried to think of a reason why this had been Enoch's fault but couldn't. In a moment, he returned.

Marilee opened her driver' s-side door. When the interior light came on, she saw it down in her footwell. It was a pale scorpion, translucent almost, with two dark stripes running the length of its body. She drew back and motioned for Enoch to come over. How did it get there? How could it have crawled inside a car ten inches off the ground? Had the cop somehow brought it in? Or had it been hiding in some cranny of Enoch's backpack? Perhaps it had been there the whole time, down by her feet as she drove east from Los Angeles.

"Get it out," she whispered.

"Easy," he cautioned. He reached down into the footwell and gently prodded the creature. It crawled onto his stubby fingers. Marilee froze. Was this guy stupid or just plain crazy? She wondered, for a moment, if Enoch might try something funny like flinging it at her or insisting she touch it. She took another step backward.

The thing crawled into Enoch's palm. He lifted it out of the footwell, but instead of tossing it into the desert, he held it in his hand. Enoch looked at the scorpion. The scorpion looked back. Its legs seemed bulbous and awkwardly hinged, as if the result of some miscue of nature. It uncoiled its tail and rose up on its legs. Marilee felt she was going to throw up.

"Get rid of it," she whispered. A trickle of sweat ran down between her breasts.

"In a minute."

The scorpion's tail arched high over its head, its stinger suspended like a hooked needle; its pincers cocked, front and open. Standing in the light of the car's doorway, Enoch studied the creature, staring it down as if daring it to strike. A passing semi whipped dust in their faces, but neither of them flinched. Each stood poised for battle. Each bided his time, eyeing the other as though they shared some indelicate secret with which Marilee could presume no intimacy.

Finally, the scorpion lowered its tail. Enoch placed it in the dirt by the side of the highway, where it crawled to safety beneath a broken Styrofoam cup.

They continued east toward Alamogordo. In less than an hour they would arrive and she would say goodbye to Enoch, dropping him off at the Y, perhaps, or maybe at a shelter. Then she would get out her map and find Larry's street. She would knock on his door in the middle of the night, and he would open it and take her into his arms.

Marilee stepped down harder on the accelerator. Her muscles ached from driving; her lips tasted of salt. Brown dirt lodged in the cracks between her toes. "I could use a shower," she said, more to herself than to her companion.

"A pool!" said Enoch. "I know a place. On the road to El Paso. It's not far. I'll show you."

A pool sounded wonderful. Clean water in which she could bathe. Cool water in which she could float away under the stars. But it was out of the question. "I didn't bring a bathing suit."

"Swim naked."

Marilee felt a tightness grip her stomach. So this was it. This was where he'd jump her. Where he'd slip his little thing into her like a snake gliding into wet moss, and she'd end up with a little dwarf child she'd have to name Elwyn. And why not? Hadn't she picked him up off the side of some road? What jury would believe her? They'd say she'd asked for it, wanted it even.

Yet a pool sounded wonderful. It was after midnight. Her hair stuck to the back of her neck like a clump of seaweed. It would be a shame for Larry to see her like this. Besides, she was bigger than Enoch. Stronger, probably, too. A pool was just what she needed. She would swim in her underwear.

"So tell me about the fire," she said.

"No."

"You said you would. 'Later,' is what you said. I'd like to hear." Marilee glanced across the seat at Enoch. His nose looked thicker in the darkness, and his face showed the first signs of stubble. "I told you about Larry," she reminded him.

"Fire!" shouted Enoch, so startling her that she nearly swerved over the center line. " Burst of light! Fireball! Like a bomb going off ! Butane. Storage tank. Erupted. Too much heat!" He was sitting on the edge of his seat, breathing hard and painting the fire with his hands. "Blowout! Exploded! Whole sky on fire!" His hand hit the rearview mirror. "Twelve people died. Twelve. Firemen," he said. "Too much heat."

Enoch stopped for a moment. He rubbed his eyes and scooted back on the seat so that his legs stuck straight out over the edge. "Rumors started," he continued, his voice lower now. "Children. You know how it is. Kids talk. Adults listen. Always the same. You're bound to be suspect if you're not like them. Grew up in that town. Guess they needed me."

Enoch stared silently at the oncoming headlights.

"I'm sorry," said Marilee.

"For what?"

"For what you went through. That's just awful. It's unfair."

"Who said life is fair?"

He had her there.

They drove the next twenty miles in silence. Then Enoch spoke. He said, "Larry's not good enough for you." It annoyed Marilee the way he said this, as if he'd been thinking about it for years. As if this dwarf had a corner on her dreams.

"VACANCY," said the sign above the Trinity Motel, a crumbling, one-story adobe that squatted upon the earth like a venerable Indian. The mo

tel lay on the outskirts of Alamogordo, a few miles south of the city, near the base of the Sacramento Mountains. Trinity Site, according to Enoch, was actually northwest.

They sneaked into the motel courtyard through an unlocked wooden gate. The courtyard was centered around the pool, a kidney bean with a slide in the middle. No lights were on in the rooms. The moon hadn't risen, but the stars shone so brightly Marilee could see Enoch clearly.

He propped his crutches against the back of a plastic chaise. Then, as if no one else were around, he took off his clothes. Marilee could not tear her eyes away from his body. Deformed. Hunched. Contorted. One hip jutted out like a knot on a tree. His legs twisted at the knees. A concavity hollowed his chest as though he'd been punched in the sternum at birth. She'd had no idea. When he stripped off his undershorts, she saw that his genitals were the size of a full-grown man's; they looked huge by comparison. How, she wondered, could a person live in such a body?

Yet Enoch seemed unbothered by his nakedness. He walked without crutches to the edge of the pool, wobbled really, heeling to the left with every other step. On crutches he'd appeared less awkward, more in control of his ungainly self. Marilee watched as he lowered his body into the water. There, he swam with ease, as though he were at home in his element.

Enoch did not look at Marilee as she undressed. Or maybe he saw her out of the corner of his eye, she couldn't tell. She removed her jeans and cotton blouse and hung them over a chair. But starting for the pool, she hesitated at the sight of Enoch's twisted body floating on the water's surface. Open. Vulnerable. Unsuspecting. He looked more insect than human, with his large torso and disjointed limbs. A water bug. Easy prey. It seemed wrong, suddenly, to feel self-conscious in the presence of someone like Enoch. She unhooked her bra and stepped out of her underwear.

When she glanced up, she saw that Enoch was now watching her. This time he made no effort to turn away. She stood motionless by the edge of the pool and let him take in the sight of her. He stared shamelessly, as if he knew she wouldn't mind. As if he sensed this was exactly what she wanted. Her heart pounded. What would it be like, she wondered, to make love to a dwarf ?

She shook out her hair and stepped down into the cool water. Enoch studied her every move. It felt strange and wonderful swimming nude, a freedom she had never known. She dove beneath the surface and let the water caress her skin, fan her hair, swirl all around her. She made waves in the water, turned somersaults, rolled onto her back. Spread her legs wide open.

What would Larry think if he could see her now? She laughed out loud at the thought of it: Larry in his loafers and button-down collar pacing at pool's edge, hissing through clenched teeth so as not to wake the occupants. Larry tossing her his jacket, remembering too late the wallet in its pocket. Larry swearing at Enoch, ordering him out of the pool, fists clenched and lip curled— a smoldering absurdity.

And Enoch— how might he respond? Slither out of the pool, tail between legs? (If he had a tail, which wouldn't much surprise her.) More likely tell Larry to go fuck himself. Splash water on his loafers. Thumb through his wallet. She smiled, a sad smile. Larry was only three miles north, in Alamogordo, yet he seemed farther from her now than the stars in the sky.

Marilee glanced over to where Enoch floated on his back. She swam to the deep end and floated next to him. What would he do with her body so close? Look at her? Reach out and touch her skin? She arched her back so her breasts broke through the water's surface. If he touched her now, would she push away or roll into his arms?

But he didn't touch her. Nor did he look at her breasts. Rather, he seemed content to float next to her and stare up into the night. The Milky Way cut a brilliant swath across the sky's blackness. She had never seen so many stars. Thousands of stars. Millions. Stars in number beyond her comprehension. Marilee listened to the faint drone of traffic from a distant highway. She felt light-years from anything familiar.

"I read a story once," said Enoch. "Science fiction by Asimov, called, 'Nightfall.' About this planet with six suns, so there's always daylight. But every couple thousand years, an eclipse throws the planet into total darkness. And when all those stars come out— stars nobody knew were there— all the people go insane."

Marilee gazed up into the desert night— so many stars it would take a lifetime to count. She felt Enoch's gnarled body bobbing close to hers in the water. So close, yet separate. Different, and alone. A strange silence took hold of her. Night silence. Water silence. Star silence. She threw her head back and let the water wash over her face, fill her eyes, stream out the corners of her mouth. Liquid smooth as desert sand. Liquid cool as starlight. She felt intoxicated by the water, the darkness, the explosion of stars. This is crazy, she thought.

Crazy, and real.