Читать книгу Rocket City - Cathryn Alpert - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

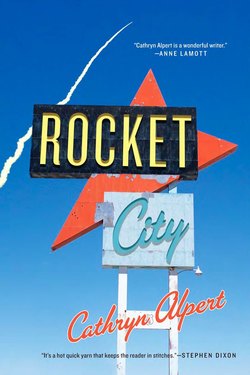

ROCKET CITY

ОглавлениеFor breakfast they ate the melons. Enoch carved them up with Marilee's knife and made fruit salad inside one of the hollowed-out rinds. They sat Indian style in the New Mexico sand, eating the slimy chunks of flesh with their fingers. Juice ran down their arms and dripped off their elbows.

They had spent the night in Marilee's Dart, parked in a turnaround on Dog Canyon Road, about ten miles south of Alamogordo. The night had been an exercise in frustration. Enoch had taken the front seat because he was smaller. He'd laid his crutches lengthwise in the footwell, fashioned a pillow out of his backpack, and promptly fallen asleep. Marilee, who had moved her suitcase into the trunk, curled up with a sweater in the back. Her five-foot-ten-inch frame was longer than the width of the car's interior and her knees buckled out over the seat's edge. Restless for most of the night, she'd listened to the rhythmic murmur of Enoch's snoring. When Larry snored, he heaved and rasped; Marilee would have to nudge him into a new position in an often futile attempt to get him to stop. But Enoch's snoring was soft and steady, like an engine idling. Eventually, it lulled her into an uneasy sleep, during which she had a number of disturbing dreams. In the only one she could remember, she was in her mother's backyard eating honeysuckle off the vines that grew over the tall back fence. Perched on top of a clothesline pole, she pulled the long pistils from their blooms and sucked the sweet nectar. She was content, thinking about what she would make Larry for dinner, when a bee flew into her mouth.

Marilee awakened with a start. She sat upright, disoriented, still able to recall the unnerving sensation of the insect buzzing against her tongue and cheeks. For a moment, she didn't remember why she had slept in her car or that there was a dwarf in her front seat. She peeked over the headrest; Enoch was still sleeping. A tiny rivulet of drool flowed from the corner of his mouth onto the blue upholstery.

Marilee looked out the window at her immediate surroundings. They had parked near the Oliver Lee General Store, a small wooden structure that looked new, yet recently abandoned. Its windows were boarded up. A sign read, "No cash left overnight." Rusty wagon wheels leaned against a tall picket fence. Marilee checked the clock on her dashboard; it was half past eight. Even with the windows cracked, the air inside the car had become stifling. She cranked down her window and squinted into the bright sunlight. The desert shimmered. A few puffs of clouds dotted the sky.

A camper rolled by them, kicking up clouds of brown dust behind it. Enoch mumbled. His face looked sullen in the light of day. Skin moist. Eyelids puffy. Cheeks covered with heavy black stubble. He could have been a character right out of one of her forgotten dreams. She nudged his shoulder. "Good morning," she said tentatively.

"Hmmph," he answered back. He sat up, looked at her, and grinned. Marilee smiled back, a queasy smile. Gathering his crutches from the footwell, Enoch flung open his door and stepped out into the bright morning. Marilee climbed out of the car after him, her back stiff from sleeping most of the night in one position.

"Gotta pee," said Enoch. He hobbled around to the rear of the building, cutting between a cistern and a windmill that appeared to have come off an assembly line. Marilee leaned against the trunk of her car and shielded her eyes from the glare. The place looked desolate: On the western horizon, plains stretched clear to the Organ Mountains. Behind her, the sheer, near-vertical cliffs of the Sacramentos stood in shadow. To the north, a few ramshackle houses hovered under a pale sky. South, toward El Paso, two faintly visible structures— huge and shaped like inverted Mayan temples— rose up from the desert floor. Marilee had no idea what they could be.

As soon as Enoch returned, they carved and ate the melons. "What's next?" he asked, toweling the juice from his stubby arms with a spare shirt from his backpack.

What was next indeed? The night before, in the motel pool with Enoch, she'd felt her life transformed as though she had been in some land of enchantment and not some blighted state with dirty toilets, greasy cafes, and state troopers who got off on badgering women and the deformed. Floating in cool water, she'd felt her life detour down a strange and dangerous road, with potholes and curves and dark cracks a person could fall into. It was Enoch's road, lonely and seductive as a two-lane desert highway.

For an hour they'd floated, staring up into the endless sky. They'd said nothing to one another, just taken in the strange silence of the desert night. In starlight, Enoch's face had seemed less awkward: intelligent, kind, and oddly familiar. But now, in the glare of morning, Marilee found herself squinting into the thick, artless features of a dwarf.

A dwarf ! She had spent the night in her car with a dwarf. A little man with stubby legs that stuck out over his seat like the stiff plastic legs of a doll. She had picked him up on the side of the highway. Swum naked with him in some seedy motel pool. Driven with him to an isolated road out in the middle of nowhere. Slept with him in her car. She must have been crazy.

And yet, it had all been so innocent. They had traveled south on Highway 54, following the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad toward El Paso. They'd turned east onto a narrow road, crossed over the railroad tracks, and driven a few miles to a turnaround. They'd locked their doors, cracked open their windows, switched off the lights, and said goodnight to one another like an old married couple, grown tired and too familiar.

She had listened to Enoch's steady breathing, aware of the exact mo

ment that sleep had overtaken him like a wave washing him out to sea. And she had listened to him dream— dwarf dreams, she imagined, of tall women, taller men, and Goliath dogs who could topple you with their exuberance. She'd listened to his noises, his muffled sputters and sudden snorts, the soft clicking of his uvula, and she'd wondered what her life would be like with a man such as Enoch.

Now, she was wondering still. Part of her wanted to run away with him, to take him as her lover and lose herself in the desolate Southwest. To travel without direction, swim naked in motel pools, have reckless sex with a man half her size, and sleep out under the stars. Yet, how could she? She was Marilee Levitay, an art teacher from Sherman Oaks coming to New Mexico to get married. Nothing in her twenty-five years had prepared her for such insanity.

Enoch watched as she traced concentric circles in the sand. "I don't know what's next," she said. "What exactly did you have in mind?"

"Well, we zip into Alamogordo. Clean up. Gas up. Get some food for the road. Then head up north, toward Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Do some pueblos. See the Jemez. Camp in the Sangre de Cristos."

He had her life all planned. "I don't know," she said, looking out into the desert. "I just don't know." He offered her his spare shirt. She took it and wiped the juice from her hands and forearms. "How are we going to live?" she asked. "What do we do for money? I don't have very much. I was planning to get a job."

"I have money," said Enoch.

He didn't look as though he had money.

"I get a check once a month."

She'd heard about these things: the government paying the disabled when they couldn't work— or didn't want to. She wondered if there wasn't something Enoch could do for a living—advertising, maybe, or phone sales. "I need to think," she said. "Let's drive up to Alamogordo. I want to change my clothes and brush my teeth."

"Yo!" said Enoch. "Alamogordo!"

At first glance, the town was not unusual. Clusters of fast-food restaurants lined White Sands Boulevard, the main drag through the western end of the city. Downtown, drab, blocky storefronts merged one into the next, their facades weathered by years of sun and sandstorms. Women in big American cars sported hairdos from the previous decade. Men strode by in ten-gallon hats, boots, and jeans— the business suit of the Southwest.

The town looked like any other she'd seen in the high desert plains, with one startling exception: Everywhere there were rockets. Rockets on top of buildings, rockets mounted on trucks, a whole configuration of rockets on the lawn in front of the Chamber of Commerce. They passed the Rocket Lounge on White Sands Boulevard, the Rocket Motel, Rocket Mobile Village, and Rockette Hair Styling. They passed a sign for Rocket Van and Storage, and a rocket on top of a sign having nothing to do with rockets. Like icons of some techno-god of the twentieth century, images of rockets dominated the city. They rose up from grass and stone; sprouted heavenward from storefront walls, restaurant doors, and the streets of Alamogordo.

"Check it out," said Enoch. "This place doesn't have soil, it has erectile tissue."

"What's that white thing?" Marilee pointed to a wing-like projection in the distance rising up from behind a mountain. It, too, looked like a rocket.

"Sunspot. Solar research lab."

"And those temple-like buildings out in the desert?"

"Haven't a clue."

There was something strange about this city, something not quite right. It was more than just the omnipresence of rockets. It was something larger and intangible. At first glance, the town had looked quite ordinary. Upon closer scrutiny, however, one saw that things were different. Odd. It was almost as though, having lived so near the first atomic test site, the town itself had mutated and grown things.

Off in the west, two fighter jets from Holloman Air Force Base wove their silvery trails high above the Tularosa Basin. They were too far away to be heard, too dramatic not to be noticed as they swung back and forth, in and out, like twin pendulums suspended from opposite points high above the cumulonimbus.

"Something's going on out here," said Marilee. "Something weird."

"Bingo," said Enoch. "You win the prize."

"And what might that be?"

He thumped his chest with his stubby hand. "Me."

They pulled into a gas station on White Sands Boulevard, where they took turns using the bathroom. Marilee washed her face in the sink and brushed her teeth, then changed into clean underwear, a blouse, and a pair of shorts. She returned to her car to put on makeup because there had been no light in the bathroom. When she opened her compact, she saw that her powder had a groove in it where the cop had run his finger. From her car, she watched through the open door to the men's room as Enoch stood on top of an overturned trashcan to shave at the sink. He looked like a five-year-old playing grownup with his father's razor.

When he'd finished cleaning up, Enoch filled her car with gas. Fumes rose from the nozzle as he pumped, wafting in through Marilee's open window. She'd always loved the smell of gasoline. As a child, sitting in the backseat of her mother's pink Buick, she would roll down her window to inhale deeply whenever the attendant pumped gas. The fumes made her dizzy, eliciting in her an indefinable yearning she later identified as sexual.

Larry's ROTC photo was still on the dashboard, faded and curled from the morning sun. His face smiled up at her, a sweet face the way his eyes squinted when he smiled and one incisor overlapped the other as though his two front teeth were bashful. She had always gone for blondes. Or maybe they had gone for her— she wasn't sure. Across the street, a rocket pointed skyward in front of an outdoor car lot. Where in this strange town did Larry live? So far, the houses all looked alike: stucco tract homes from the post-war building boom and cottages from the thirties. Where were the apartments? The condos? Where was Tomahawk Trail?

Marilee smoothed Larry's photo as best she could and slipped it back into her wallet. Leaning back against her headrest, she closed her eyes and drew in the heady odor of gasoline. She'd missed sleeping with Larry; in the seven months since he'd left L.A., Marilee had slept with no one.

She'd first met Larry Johnston when she was seventeen. Theirs had been a large high school in the San Fernando Valley in which a student could easily remain anonymous. But not Larry Johnston. Even before he turned up in her German class, Marilee knew of him as a loner, an odd boy who occasionally exhibited unconventional behavior. Once, he'd pinned a calcified praying mantis to the lapel of his sweater. Another time, he'd consumed a handful of salt pills before a track meet, a dose that had caused him to faint halfway around the field.

Weird was the word most commonly used to describe Larry. He wore penny loafers without socks, and suspenders before they came back into fashion. He sang in the hallways. He wrote poetry. Marilee and Amanda Wiggins would watch him from the lunch quad: his shoulders butted against the trunk of some tree, his blond hair swept straight back, a copy of Howl propped up on his knees. The two girls would laugh as they ate their sandwiches and gossiped about couples, parents, teachers, and what Mary Ellen Kazloff was planning to do about that baby growing in her womb.

Larry, though bright, was a poor student. Occasionally, his teachers could be overheard discussing his wasted potential as if they were talking about some stock market tip they should have taken or a house they'd sold before the market boomed. Marilee thought school must have bored Larry. He got A's in English and C's in most everything else including German II, where he sat in the back corner directly behind Marilee.

"Achtung," he whispered in her ear on the second day of class. "Marilee, wie geht's?" Frau Göckermann, pert in her gingham shirtwaist dress and patent leather spike heels, stood face to the blackboard conjugating endless tenses of irregular verbs, which, when spoken in succession, had all the sonance of a Hitler rally.

Larry's voice had startled Marilee. She glanced over her shoulder, but he motioned for her to face forward. Robby Franz, who sat in the seat next to him, whistled softly through his fat lips. Robby thought himself cool. He played lead guitar in a band called Spew, did Ecstasy every weekend, and was the reason Mary Ellen Kazloff cried in the hallways.

Later, when Frau Göckermann once again had her back to the class, Larry parted Marilee's hair with his fingers. She felt his breath on the back of her neck like whiffs from a horse's nostrils. Her nipples stiffened. "Wer bist du, Marilee?" he whispered. The down on her arms rose; her heart pounded. Larry leaned farther over his desk and muttered again into her mass of red curls. "Marilee, du bist ein schöner Schmetterling. Ein Blümchen. Ein Stern in der Nacht." She froze, not knowing if he was being serious or making fun of her. Robby smirked. Frau Göckermann conjugated the verb "to click."

Convinced, after the first two weeks, that she was not the butt of some joke but rather the object of his true affections, Marilee Levitay began looking forward to sixth period. Larry's whispering had become a daily ritual she'd come to anticipate with ever-mounting states of arousal. Soon she began carrying heavy sweaters to school. On rainy days, when the windows were closed and the radiator knocked and spit with a vexing precision, Marilee would feel the warm, dry air; the heat from her body, rising; the rhythmic pulse of Larry's breath on the nape of her neck, and she'd feel dizzy and hot as a cat trapped in a spinning dryer.

That semester she did not learn much German. Indeed, all her grades suffered. During periods one through five, she spent her class time writing Larry's name on endless snippets of blue-lined paper, which she popped into her mouth, sucked beyond recognition, and collected in a ball in the zippered compartment of her notebook. Each night, after her mother left for work, she flushed the offensive wad down the toilet.

She did other childish things. She phoned Larry at home just to hear his voice, hanging up as soon as he answered. On the weekends, she spied on him at his job at Mojo's Books and Coffee Beans. From the sanctuary of the pizza parlor across the street, she watched him through the coffeehouse window, making cappuccino, slicing fruit pies and carrot cakes, microwaving bagels and lemon poppyseed muffins. At night, in bed, she mouthed her passion into her pillow in much the same way he directed his, by day, at the back of her head.

"He's a geek," said Amanda. Wearing an old pink bathrobe, she sat rolling her hair on empty jumbo-size cans of Swanson's Chicken Broth. Her face was covered in green cleansing masque. "Have you ever seen his poetry?" Marilee had to admit she hadn't, whereupon Amanda pulled open the bottom drawer of her dressing table and produced a stack of old Guardians. She tossed them onto the bed next to Marilee. "There's a real howler in there, toward the end of last year."

Marilee thumbed through the stack of school newspapers, somewhat wary of what she might encounter. She came upon pictures of the football team and the Home Club Bake-Off. She relived the crowning of Victoria Van Antwerp as prom queen and the Drama Club's production of Billy Budd. She leafed through articles about Spring Fair, college recruiters on campus, and National Merit scholars. Finally, in the May 23rd issue, she came upon a poem by Larry:

MY SPIRIT by Lawrence H. Johnston

tortured twisted thoughts

spin their web around my muddled mind

twisting, constricting

will there always be this darkness?

am I free to be

or am I caught

between the crumpled pages of a time-worn novel?

and yet, from some far-reaching destiny a pure white ray of light

filters in between the masses and the gases

swirling 'round

the tortured twisted visions

of this slumbering child

it is the ray of Hope

"It's not that bad," said Marilee.

Amanda swiveled on her stool and glanced at Larry's poem, wrinkling her nose as if she were opening a thermos that had been left in her locker all summer. "Read it out loud," she said to Marilee. "I dare you."

"I don't need to read it out loud."

"I want to see you keep a straight face when you get to the part about the masses and the gases."

"All right, okay," said Marilee. "So it's not Dylan Thomas. It's not dog doo either. There's some nice lines here, like this part about the pages of a time-worn novel. I like that."

Amanda shot her a tortured look. With her hair set on soup cans and her face the color of strained peas, she looked as if she might have stepped out of a first-season episode of "Star Trek."

Marilee walked home briskly that evening, annoyed that her friend could, at times, be such a brainless snot. The truth was, Marilee hadn't found Larry's poem all that objectionable, although she had to concede that the part about the masses and the gases was pretty awful. Still, he had a way with words, a sensitivity to the natural rhythm of language. She resented Amanda's making fun of him as if he were some tormented soul drowning in the quagmire of his own angst. That wasn't Larry at all.

But then, what was? For fifty minutes, five days a week, he whispered into her neck in German. This was strange, she had to admit. Stranger still was his habit of slighting her otherwise. Each day when the final bell rang, he was out the door before Marilee could even rise up out of her seat. If she passed him in the hall between classes, he'd refuse to acknowledge her. His behavior was baffling. Marilee understood his intentions to be sexual, but his style was so different, so utterly unnerving, that she was at a loss as to how to respond. She considered joining him at lunch some day, or milling about his locker, but realized she was simply too timid to carry through with either plan. So she played the game his way, pretending not to notice him when their paths crossed, ignoring him each time he whispered his guttural soliloquy.

"Mein süßes schönes Täubchen," Larry said into her hair one cold, drizzly Monday. Marilee scratched through her sweater at the trickle of sweat that ran down the length of her ribcage. "Mein Liebling," he whispered, then kissed the back of her neck. Marilee gasped. Robby snorted. Frau Göckermann spun on her heels, glaring toward the back corner.

"Who laughed?" she demanded. The room became abruptly silent. "All right," she said. "No one is leaving until I get an answer."

"I did," said Larry. Robby Franz relaxed in his seat.

"Please see me after class," said Frau Göckermann, who promptly assigned the class six pages of homework, which they were to begin immediately. Cindy Burris pivoted in her seat and shot Larry an evil look. Frau Göckermann said nothing until the bell rang. "Marilee, I'd like to talk to you as well. Please wait for me outside in the hallway."

"Shit," mumbled Marilee, as Larry passed her on his way to the front of the classroom. She stalled until most of the others had left, arranging and rearranging the papers in her notebook. Occasionally, she sneaked glances at Larry as he stood in front of their teacher's desk, his weight balanced on one leg, thumbs hooked in his pockets the way she imagined James Dean would have stood before a woman who wore patent leather spike heels and spoke German. Marilee strained to hear Frau Göckermann, but the woman's voice was drowned out by the din from the hallway. She got up slowly and left the room.

The hall was buzzing. Students swarmed the stairwells, slamming books into lockers, switching on radios, calling to one another from the building's opposite ends. She leaned back against the wall, her neck and shoulders tight and aching. Eau de School Bus permeated the air, a heavy mingling of diesel fuel and road grime that wafted down the corridor like slow poison. Cars sped by in front of the flagpole, splashing rainwater as they screeched out of the parking lot, running on high octane and testosterone. Kevin Thacker asked Marilee if she wanted a ride home, but she declined. In a few minutes, Larry emerged from the classroom.

"As ye sow, so shall ye reap," he said, holding the door wide open. They were the first words he had ever spoken to her in English.

She brushed past him into the room. Frau Göckermann sat at her desk. "You have an admirer," she said with a tight smile. "Don't think I'm not aware of what goes on in my classroom."

"I'm sorry," said Marilee.

"Don't apologize, dear. But do be careful. I've seen his type. I know what a boy like that can do to a young girl. Take my advice, dear, forget about him."

Marilee was speechless. She hardly knew whether to be insulted by the woman's presumption or flattered by her concern. She looked down at the desk, hoping to be dismissed.

"At any rate," Frau Göckermann continued, "it's time to break up your little tea party. I've moved Herr Johnston (she pronounced it Yonschton) to the front of the class, where, I hope, he will be less inclined to be disruptive."

Marilee's heart sank.

"Das ist Alles," said Frau Göckermann, turning her attention to the papers on her desk.

Marilee walked out of the classroom. She trudged down the empty hallway and outside into the rain, her books heavy in her arms. "You missed your bus," said a voice behind her. Larry stood leaning against the red brick wall of the building, much as she imagined James Dean would have leaned against a red brick wall. "I'll take you home," he said. He walked her to his car, talking to her about Hemingway. About big game hunting. The running of the bulls at Pamplona. Existential suicide. He said nothing about having kissed the back of her neck.

"Why'd you do that in there?" she interrupted, once they were seated in his red Pinto.

"I like Robby," he said, misunderstanding. He jammed his Pinto into gear and squealed out of the parking lot.

On the way home, he told her about his car: '71. A good year. Four on the floor. Twenty-five miles to the gallon, a real gem. You couldn't buy cars like that anymore. Pulling into her driveway, he threw his stick shift into neutral and pulled up on the emergency brake. The Pinto screeched to a halt. "She's old, but she's loyal," he said, running his hand along the steering wheel. Guys were weird about their cars.

"Thanks for the ride," said Marilee, flinging open the passenger door.

Larry shrugged. "Frau G. changed my seat."

"I know."

"So, I'll pick you up tomorrow morning around eight," he said, as if one thought led naturally to the other.

"Quarter to eight," said Marilee, gathering her books, trying to remain cool.

"Sehr gut," said Larry.

"See ya," said Marilee. As she stepped out of his car, her skirt rose up high on her thigh; she made no effort to pull it down.

"It's all yours," said a voice at her driver' s-side window. She opened her eyes. Enoch thrust the stick end of a windshield scrubber at her. "Excuse me?"

"Can't reach across the windshield. Sorry."

Marilee smiled weakly, then took hold of the dripping apparatus.

"I'll go pay," said Enoch. "Want anything?"

She shook her head no.

Enoch entered the building awkwardly on his crutches. Marilee stepped out of her car and went to work scraping bugs from her windshield. Occasionally, she sneaked glances at Enoch standing in line for the cashier. He stood no taller than the two little boys in front of him, one staring, the other giggling, both holding tightly to their father's hand. The man wore cowboy boots and an orange Broncos hat. Enoch smiled at the boys. The smaller one said something back, and the man whisked him into his arms.

When she was finished with her windshield, Marilee wetted some paper towels and wiped road grime from her headlights. Old as it was, she was fond of her Dart, a gift from her mother after Larry had left L.A. Ramona Levitay had picked up her daughter after work one day and driven her down to Aspromonte's. Ramona knew Nick Aspromonte from the club where she worked as a coat checker. Nick had a brother, Philly, who owned a car lot down on Van Nuys Boulevard.

Philly cut Ramona a sweet deal on the Dart. The car was unique, he said, because it had a clock on the dashboard. This model Dart never came with a clock, but the previous owner had installed one, special. She could have it for three-fifty. Marilee knew nothing about cars, but she liked its shade of blue. Amazingly, the Dart ran like a dream. It got twenty miles to the gallon and its clock kept time.

Both boys in his arms now, the man in the Broncos hat emerged from the building and headed toward a white pickup truck with a gun rack mounted in its rear window. Enoch moved up to the counter, barely tall enough to see over its edge. He pulled his wallet out of one of his socks and handed the cashier some bills. Having finished cleaning her headlights, Marilee polished her side mirror, then resumed her place behind the wheel.

Enoch struggled to open the glass door. A woman in line studied him as he propped the door open with one crutch, then hobbled through on the other. It would always be this way, thought Marilee: People staring, too absorbed in Enoch's awkwardness to avert their eyes. Too ill at ease to lend a hand. Too self-contained in their safe little spaces to make contact with a dwarf. And they would wonder about her. Were she and Enoch friends? Lovers? What weird things did they do in bed?

A Tootsie Pop came flying through the open passenger-side window. Marilee caught it between her knees. "Jack up your endorphins," said Enoch, tossing his crutches into the back and reclaiming his seat next to her. "Like heroin. Or being in love."

Marilee looked over at the small stranger sitting next to her, white stick protruding from his mouth. She wondered if he had ever been in love, or if anyone had ever been in love with him. She started her engine, pulled out of the filling station, and headed north on White Sands Boulevard. She had no idea where they were going. Annoyed, she tossed her Tootsie Pop on the seat between them where the melons had been. Enoch picked up the sucker, unwrapped it, and inserted it between her lips.

"Thanks," she mumbled, working the stick with her tongue.

"My pleasure," said Enoch.

It was grape, a flavor Marilee hated.

They headed north toward Albuquerque. A few miles out of town, just past North 54 Salvage, Marilee pulled over to the side of the road.

"I can't do this," she said. She took the Tootsie Pop from her mouth and switched off the car's motor. "I can't just take off like this. This is crazy."

"Okay," said Enoch.

"I've got to go back," she continued. "I'm sorry. This has nothing to do with you. It's just that I can't walk out on Larry like this. He's—"

"No problem," said Enoch, reaching for his crutches and his backpack.

"Look, you don't have to get out here. I'll drive you back into town."

"Fine," said Enoch.

"I'm really sorry. I just can't—"

"You done with that?" He was staring at her Tootsie Pop.

"You don't want this?" said Marilee. She was just getting down to the good part.

"Only if you're finished."

Marilee handed him her half-eaten sucker and restarted her engine. She made a U-turn and headed in the opposite direction, just as she had the day before when she'd first spotted Enoch on the highway. Enoch twirled the sticks in his mouth and hummed "Moon River" as she drove back to Rocket City.

"Where would you like me to drop you off ?" she asked, as soon as the highway had once again become White Sands Boulevard. She was tired of Enoch's humming; irritated by his casual indifference.

"Anywhere," he said.

"Do you want me to take you downtown, or drop you off here?"

"Whatever."

His attitude annoyed her. She wished he would yell at her or call her names. On Tenth Street she turned left, then made a quick right onto New York Avenue. "How's this?" she said, stopping suddenly beside a bench on the sidewalk. It wasn't a bus stop as far as she could tell; there was no sign or special lane leading up to it. It was just an ordinary, lime-green bench sitting next to the curb in the middle of the block. Weird, she thought. And appropriate.

"Excellent," said Enoch, opening the door. Cars backed up in the lane behind them. A man in a Cutlass tooted his horn until he saw Enoch struggling with his crutches.

"Well, I guess this is it," said Marilee.

"I guess so," said Enoch.

"It's been fun, really," she said, then hated herself for having said that. Enoch slung his backpack over his left shoulder and maneuvered the door shut with one crutch. "Bye," she called through the open window.

"Thanks for the ride," said Enoch.

"Take care," said Marilee.

"Have a good life," said Enoch.

"Let's go!" yelled the man in the Cutlass.

"Fuck you!" shouted Enoch.

The man in the Cutlass honked loudly as Marilee accelerated. She watched Enoch in her rearview mirror. He didn't try to hitch a ride or get up and walk away. He just sat there on the bench-from-another-planet, watching Marilee drive down the street and out of his life.

She signaled to turn left at the first intersection. She had no idea where she was going or what she would do once she got there. It would be hours before Larry arrived home, hours she would have to kill. She glanced again in her rearview mirror at the small lump that was Enoch. He sat alone on the bench, staring in her direction. He waved. She winced and pretended not to have seen him.

A group of blind children stepped off the curb and started to cross the street in front of her. She had not seen them waiting. There must have been twenty of them, shuffling en masse in a tight swarm, tapping their way across New York Avenue. They tapped slowly. As soon as the last of them had cleared the intersection, Marilee rounded the corner, and Enoch passed out of her sight.

The clock on her dashboard said quarter past ten. It was Tuesday in Rocket City.