Читать книгу A Life Lost - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 11

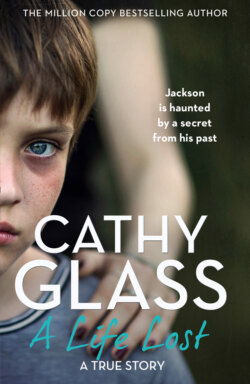

Jackson

ОглавлениеFrankie led the way into a small room where a colleague of hers was sitting, talking to Jackson. ‘Thanks, Aaron,’ she said.

Aaron nodded, said goodbye and good luck to Jackson, then left.

Frankie sat in the chair Aaron had vacated. The room was just big enough to take a small desk, two office chairs and a filing cabinet. Kayla and I stood to one side. The room was on the third floor and looked out over the car park below.

‘Jackson, I know this is difficult for you,’ Frankie began gently. ‘How are you feeling now? A little less upset?’

Jackson shrugged despondently. He wasn’t holding his phone, so I guessed it was in his pocket.

‘I’ve talked to you about why you’re staying at Cathy’s for a while,’ Frankie continued. ‘Do you have any questions?’ Jackson shook his head. ‘OK. We think it’s best if you go straight to Cathy’s now and then I’ll bring some of your belongings later. Is there anything you would particularly like me to bring today?’

Jackson kept his head down and didn’t reply.

‘I’ll make sure I put in your phone charger,’ his mother said.

Jackson said nothing.

‘You’ll be able to collect some more of your belongings another day,’ Frankie said. ‘And obviously you’ll want to see your mother and sisters regularly. So we thought tomorrow and then Monday, Wednesday and Friday after school. You and your mother can also phone on the days you don’t see each other. How does that sound?’

‘Not fussed,’ Jackson said with another shrug, head down.

But of course he was ‘fussed’. He was hiding behind a couldn’t-care-less attitude to protect himself from further hurt. He’d be feeling rejected – most children coming into care do, even though the reasons for the move have been explained to them.

‘I want to see you,’ Kayla said touchingly.

‘What if I refuse to go with her?’ Jackson asked, raising his head and glaring at me. ‘You can’t make me go. None of you can.’

‘We think it’s best for you at present,’ Frankie replied sensitively. ‘It will be a bit strange to begin with, but it will allow you some space. You will be able to attend the same school, so you’ll see your friends.’

‘You could have some friends back at the weekend,’ I suggested, thinking this might help.

There was a moment’s pause, then Jackson jumped up and, barging between his mother and me, left the room.

We all went after him. Aaron was in the main office and, seeing Jackson run off angrily, gave chase. He went ahead, trying to catch up with him, as Frankie, Kayla and I followed. We went through some double doors and down a flight of stairs. Aaron and Jackson weren’t in view. I was even more anxious now. If Jackson felt he could behave like this with all of us present and in front of an open-plan office full of social workers, what chance did I have of controlling his behaviour when it was just him and me? I shuddered at the thought. Sometimes a child’s behaviour is so challenging that they can’t live in a foster home and have to go to a therapeutic children’s home to receive the help they need.

We went down a second flight of stairs and arrived in reception. Aaron and the security guard had Jackson standing between them. We went over.

‘Thank you,’ Frankie said to the guard and Aaron.

But at that moment the main doors automatically opened as someone came in and Jackson seized the opportunity and shot out. Kayla let out a small cry. Aaron went after him, followed by Frankie, Kayla and me. There was a busy main road not far away, but thankfully Aaron managed to stop Jackson before he got there. Lightly holding his arm, he began to talk to him, trying to calm him down.

‘Aaron is one of our outreach workers,’ Frankie told me and Kayla.

We waited a little way off as Aaron continued to talk to Jackson and slowly he seemed to calm down. Aaron took his hand from Jackson’s arm and continued talking to him in a low, even tone. Kayla’s phone bleeped with a text.

‘I need to go,’ she said anxiously as she read the message. ‘I promised my neighbour I’d be back by four-thirty to collect my daughters. I’ll catch the bus.’

‘I’ll wait until Jackson is on his way to Cathy’s,’ Frankie said. ‘Then I’ll come to see you later.’

Kayla went over to say goodbye to Jackson, but he turned his back. The poor woman – I felt so sorry for her. I instinctively wanted to tell Jackson not to be so rude to his mother, but he’d only just calmed down and I knew it would do more harm than good. Kayla seemed used to his rudeness and went on her way to catch the bus.

‘Where is your car?’ Frankie asked me.

‘Parked in a side road about a five-minute walk away.’

‘Could you bring it here? It might be easier to get Jackson in.’

I could see why Frankie thought that would work better than walking him to where my car was parked. There is a drop-off/collection bay at the front of the council building that takes one car at a time.

But as I went to fetch my car, I again wondered how I was going to manage Jackson when it was just him and me. I was already stressed; my heart was pounding. It’s always a bit nerve-racking meeting a child and their parents for the first time, but this was far worse than usual. Not because of Kayla – she was lovely. It was Jackson. I’d looked after children before with challenging behaviour, but his habit of bolting when he was angry or upset was very unsafe for him and difficult to control.

Arriving at my car, I engaged the child-locks on the rear doors so they could only be opened from the outside, just in case Jackson had any plans to make a dash for it if I stopped at traffic lights. I drove to the council offices, wondering if I was taking on more than I could manage, but then I chided myself. Jackson was only ten. He was angry and upset because his father and brother had died. I needed to concentrate on helping him through the grieving process so that hopefully he would eventually come to terms with his sad loss.

As I pulled into the collection bay at the front of the council offices, Frankie and Aaron came forward with Jackson between them. Setting my face to an encouraging smile, I got out.

‘OK, love?’ I said to Jackson, opening the rear door. ‘It’s about a twenty-minute journey to my house.’

He hesitated, glanced around, but then got in. I breathed a sigh of relief, as I’m sure Frankie and Aaron did.

‘Look after yourself,’ Aaron said.

‘I’ll see you later,’ Frankie told Jackson. But he was already concentrating on his phone.

I closed the rear door and got into the driving seat as Frankie and Aaron returned to the council offices.

‘Can you put on your seatbelt, please?’ I said to Jackson, fastening my own. He ignored me so I turned in my seat to face him and said more firmly, ‘Jackson, you need to put on your seatbelt, love.’

He ignored me for a while longer and then, annoyed, did as I’d asked, ramming the metal tongue into the buckle.

‘Well done,’ I said. Before pulling away I quickly texted Paula and Tilly, who were at home, to say we were on our way.

As I drove, I periodically glanced in my rear-view mirror at Jackson, checking he was all right. I talked to him, trying to put him at ease, and asked him about his school and friends. He didn’t reply, look up or make eye contact in the mirror, but kept his head down, concentrating on his phone. It was only when I pulled onto the drive at my house that he finally spoke.

‘I’m not staying here,’ he said. ‘I’ll run away.’ He tugged hard on his door handle. ‘You’ve locked me in!’

‘I keep it locked for when I transport younger children,’ I said, bending the truth slightly. ‘Stay there and I’ll open it for you.’

I got out and went round. At the same time our front door opened and Tilly and Paula appeared.

‘Hello,’ I said with a brightness I didn’t feel, and opened Jackson’s door. ‘Come and meet Paula and Tilly.’

As Jackson got out, I saw his gaze flicker up and down the street. Our small driveway was open plan, so there was nothing to stop him running off.

‘Come on, this way,’ I said feigning confidence.

‘Hi, Jackson,’ Tilly called enthusiastically from the front door.

He ignored her but did come with me into the house. I quickly closed the front door.

‘This is Tilly, who is also staying with us, and my daughter Paula,’ I said.

‘Hi, how are you, Jackson?’ Tilly asked. Then she looked hurt when he ignored her. Paula, on the other hand, having grown up with fostering, appreciated that our new arrivals often needed time to settle in and adjust.

‘Would you like a drink and a snack?’ I asked him. ‘Or to see your bedroom first?’

He shrugged.

‘I can show you your room,’ Tilly offered.

‘No. I’ll see it myself,’ he replied grumpily, and began upstairs.

‘It’s on the right,’ I said, going after him.

As we went into his room, I heard Tilly say to Paula, ‘He’s so rude.’

I guessed Paula would explain and I would have a chat with Tilly too, later.

‘The room is a bit bare, but it will look better once you have some of your belongings in it,’ I said to Jackson. ‘Frankie is going to collect them and bring them here later.’

He went over to the window, glanced out, then sat on the bed and concentrated on his phone.

‘Are you playing a game?’ I asked him, trying to establish some communication. I’d caught glimpses of the screen and thought that might be so, although I doubted Jackson was getting much pleasure from the game. It seemed more like mindless tapping as a displacement for what he was really thinking and feeling.

He didn’t reply so, going over, I said, ‘I know it’s difficult, love. You’ve suffered a great loss and now you’re having to live in a strange house with people you don’t know. It will get easier, I promise, and I am here to help you.’

‘I don’t need your help,’ he said resentfully.

‘I think we all need help sometimes. Do you have any questions you would like to ask me now?’

He shook his head, although I knew he must have plenty.

‘Would you like to see the rest of the house?’ I asked. I usually show the child around early on as it helps them settle and feel at home. Jackson shook his head again. ‘Maybe later then. What would you like to do now?’

He ignored me.

‘I was thinking of making a lasagne for dinner. Do you like that?’

‘Not fussed.’

‘OK, but I don’t want you sitting up here by yourself.’

‘Can if I want,’ he replied.

Despite his bravado, I felt sorry for him. He looked so lost and alone, sitting there on the edge of the bed, shoulders slumped forward, pretending he didn’t care. I’d seen children before trying to put on a brave face when they were scared and hurting inside. His mother had said he wouldn’t talk to her about his feelings, but not opening up was only prolonging the agony for him. I was about to suggest he come down and sit in the living room when his phone rang.

‘It’s Mum,’ he said, his face brightening a little. But instead of answering, he rejected the call.

‘Why did you do that?’

‘I don’t want to talk to her.’

‘Couldn’t you just say hello and let her know you’re all right?’ I suggested.

He didn’t reply.

‘I’ll give her a ring then,’ I said. ‘She’ll be worried about you.’

‘No, she won’t,’ he retaliated.

‘Jackson, I know you’re feeling rejected. But your mother loves you and will be missing you a lot. You all need some time and space to get through this, but she has feelings too. She’s grieving like you and your sisters are, but she’s having to hold your family together as well.’

‘We’re not a family any more!’ Jackson snapped, and I could hear the pain in his voice.

‘You are a family, love, just a different one. I know this isn’t exactly the same – my husband didn’t die, but he left us many years ago when Adrian and Paula were little. We all had to adjust to life without him, difficult though it was, so we could see a way forward. In time and with counselling, you will be able to see a future too.’ I had no idea if I was saying the right thing, as I’d never experienced the devastating bereavement Jackson had, so I was relying on common sense.

Jackson didn’t say anything, but he must have heard what I’d said. Hopefully he would think about it and know I was there for him, just as his mother was.

A knock sounded on his bedroom door – I’d left it ajar – and Tilly appeared. ‘Hi, I’m in care too,’ she said to Jackson. She was bright and sparkly and wanting to help, but the timing was wrong.

‘So?’ Jackson said under his breath.

‘I’m just saying. I thought it would help.’

I threw her a reassuring smile. Jackson’s phone rang again and this time he accepted the call. ‘What do you want, Mum?’ he asked, his voice flat. But at least he’d answered.

‘Come on,’ I said quietly to Tilly. ‘We’ll leave Jackson to talk to his mother.’

We went out and I drew the door to but didn’t completely close it. I went with Tilly into her room. ‘He’s very moody,’ Tilly said.

‘Don’t take it personally. He’s had a lot to cope with.’ I’d already told her and the rest of my family what they needed to know about Jackson’s loss.

‘Can Abby come round this evening?’ Tilly asked. Abby was her best friend and they saw a lot of each other.

‘Yes, if her parents can collect her. I can’t leave Jackson with Paula at present.’ My daughter Paula was one of my nominated sitters – police checked and approved by the social services – but I’d never leave a new arrival with her. They needed to have settled in first.

‘They should be able to,’ Tilly said. ‘Can Abby stay for dinner?’

‘Yes, it’s going to be lasagne.’

‘Great.’

Although this would mean another new person for Jackson to meet, I’d found in the past that it helped the child to relax if everyone continued with their plans as usual.

‘I’ll phone her now,’ Tilly said. Then she paused and looked at me seriously. ‘Jackson’s very young to have a mobile phone, when you think what happened to me.’

‘I know, love, but I understand there is a parental control app on it. I’ll check it when I have the chance and make sure it’s up to date and doing its job.’

Tilly had learnt the hard way that while having a mobile phone had many advantages, it was also open to abuse. The poor girl had been to hell and back and as a result of what had happened still wasn’t talking to her mother.

Leaving Tilly to call Abby, and Jackson on the phone to his mother – listening rather than talking – I went downstairs. Paula was in the front room using the printer. We all had our own laptops but shared the printer. Having graduated in the summer, like many young people she was finding it difficult to get a permanent job and was temping in the meantime. We chatted for a few moments and then I said I was going to start dinner and asked her to let me know if she heard Jackson moving around. From his room to the front door was a straight run down the stairs, and I wouldn’t have put it past him to try to leave. Foster carers can’t lock children in the house, even if it is for their own good, so I put the safety chain on the front door, which would at least slow him down a bit.

I was right to be cautious, for five minutes later I heard footsteps on the stairs and then Paula ask, ‘Are you OK, Jackson?’

I went quickly into the hall in time to see him at the front door.