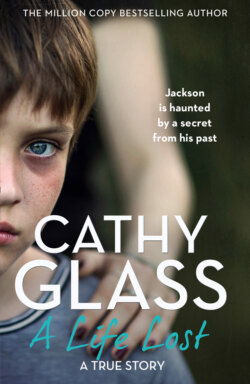

Читать книгу A Life Lost - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Tragic

Whatever can you say to a woman whose husband has died and whose teenage son has committed suicide? I didn’t know if the two tragedies were connected; Joy, my SSW, who’d given me the details, wasn’t sure. I was now driving to the council offices where the meeting was being held with thoughts of the family going through my head.

I knew from the placement information forms that Jackson’s mother, Kayla, was thirty-nine and had been widowed two years ago. A year after she’d lost her husband from cancer, her eldest son, Connor, aged seventeen, had hanged himself. Yet somehow, she’d managed to carry on and I admired her courage. I supposed she felt she had to for the sake of Jackson and her two daughters, Jenna, aged seven, and Grace, five. My heart went out to them. What they had all been through was unbelievably sad; truly the stuff of nightmares and devastating for the whole family. I understood that concerns about Jackson’s behaviour had been raised by his school the previous term, then during the summer holidays Kayla had reached breaking point and had gone to her doctor, who had contacted the social services. Kayla had admitted she was unable to cope with Jackson’s behaviour any longer and had agreed to him going into care. How long he would be with me I didn’t know.

I parked the car in a side road close to the council offices and, summoning my courage, got out. Tragedies like this one reminded me how lucky I was. My children were all healthy. I’d lost my father a few years before, but he’d been in his eighties when he’d died. Thankfully my mother was still doing well. It seemed to me Jackson’s family had been given an unfair share of life’s misery.

Going into the council offices, I registered at reception and, with my ID pass looped around my neck, went upstairs to the room where the meeting was to be held. I’d brought a small photograph album with me to show Kayla so she had some idea of where her son would be living. Because she had placed Jackson in care voluntarily under what’s known as a Section 20 (of the Children Act), and there were no safeguarding issues, she would probably be given my contact details. If a child is brought into care as a result of abuse and is the subject of a court order then generally the parents aren’t told where they are, although some find out.

I knocked on the door of the meeting room and went in. Seated at the table were two women and a young lad who I took to be Jackson. I was slightly surprised to see him there, as Joy had said this meeting was just for Kayla to meet me.

‘Cathy, I’m Frankie, the family’s social worker,’ said one of the women, greeting me. ‘This is Kayla and her son Jackson.’

‘Pleased to meet you,’ I said, joining them at the table. ‘I am so sorry for your loss.’

‘Thank you,’ Kayla said in a small voice, while Jackson glared at me.

Although he was sitting down, I could see he was tall for his age but willowy and slightly built. He had dark hair and beige skin, the same as his mother. But whereas her eyes showed deep sadness, Jackson’s shouted anger and confrontation. Having thrown me a disparaging look, he concentrated on the mobile phone he held in his lap. It might surprise you to know that nearly half of all children aged five to ten have a mobile phone. I hoped his mother had put parental controls on it.

‘We thought it best if Jackson joined the meeting,’ Frankie said to me. ‘Kayla’s daughters are being looked after by a neighbour.’

I nodded. The schools didn’t return from the summer vacation until the following week, so Kayla would have had to make childcare arrangements to attend this meeting. I hadn’t met Frankie before but she had a calm, confident manner.

‘How are you, Jackson?’ I asked, trying to engage him.

He shrugged and continued to tap the keypad on his phone. His mother looked at me, slightly embarrassed, and I threw her a reassuring smile.

‘Kayla asked to meet you,’ Frankie said to me. ‘She thought it might help. Perhaps you could tell us a bit about yourself, your home and family.’

‘Yes, of course. I’ve brought some photographs with me.’

I placed the album on the table in front of Kayla and Jackson. As Kayla began to turn the pages, I said a few words about each photo. The first was a group photo of us standing at our front door as if welcoming in our new arrival. I told them the names and ages of my children, including Tilly, aged fourteen, who I was fostering, and said that Lucy now lived with her partner and their baby not far away. The rest of the photos were of the house – downstairs, upstairs and then the back garden. The very last was another group photo, taken in our back garden with a selfie stick and including our cat, Sammy. ‘Do you like cats?’ Frankie asked Jackson as I finished.

He shrugged dismissively and stared at his phone.

I hadn’t had time to include a photo of Jackson’s bedroom because until now it had been Lucy’s room, so I showed them the photo I’d taken on my phone before I’d left the house. Jackson kept his gaze down. Kayla thanked me and handed back the album. I then talked a bit about my family, our routine and what we liked to do in our spare time, which was expected at these introductory meetings.

‘How long has Tilly been with you?’ Kayla asked.

‘Eight months.’

‘Is she staying for good?’

‘I don’t know,’ I replied truthfully.

‘Why is she living with you?’ Kayla asked.

‘I’m afraid I can’t really go into details,’ I said awkwardly, glancing at Frankie. ‘It’s confidential. She can’t live at home, so she is staying with us for the time being. She’s settled in very well.’ (I tell Tilly’s story in A Terrible Secret.)

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Frankie said, then to Jackson: ‘I expect you have lots of questions. Is there anything you would like to ask Cathy now?’

He shook his head and tapped his phone.

‘Jackson, can you please put down that phone!’ his mother exclaimed, desperation in her voice. ‘People are talking to you. It’s rude to ignore them.’

‘So?’ he snarled aggressively. ‘You can’t tell me what to do.’

‘You would never have spoken to me like that if your father had been here,’ Kayla said, tears springing to her eyes.

‘And we both know why he’s not here!’ Jackson retaliated.

There was a second’s pause before he suddenly jumped up, sending his chair clattering across the room, and stormed out, kicking the door shut behind him.

‘I’ll go after him,’ Frankie said, and left the room.

Kayla took a tissue from her bag and pressed it to her eyes. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘I don’t know what to do with him any more. He’s so angry. He blames me for his father’s death.’

‘But why is he blaming you?’ I asked. ‘I thought your husband died of cancer.’

‘He did, but Jackson says I should have made him go to the doctor sooner. He’d been complaining of stomach pains after he’d eaten, but I thought it was just indigestion. We’re not a family that’s always running to the doctor. By the time they found the cancer it was too late. It had spread all over his body. He was dead three months after diagnosis – two years ago now.’

‘I am so sorry,’ I said, and felt my own eyes fill. ‘What a dreadful loss. But it wasn’t your fault.’

‘He was a good man. I loved him so much. Jackson wasn’t able to talk about his father or what he was feeling, and would storm off if he was mentioned. Then a year later Connor, my eldest son, took his own life, and Jackson fell apart. He blames me for his death too.’

Words failed me. Sometimes a person’s loss is so great that it’s impossible to find the words to express meaningful sympathy. ‘I am sorry,’ I said again quietly.

We were silent for a few moments and then I asked: ‘Has Jackson had any bereavement counselling? I know it can sometimes help.’

‘No. Our doctor suggested it, but he won’t go. He’s closed in on himself. The only way he expresses his loss is through anger. It builds up and then he explodes. My daughters are different. They talk about their dad and brother and say how much they miss them. They come with me to the cemetery, but Jackson won’t.’

‘I expect Frankie will suggest counselling. It’s usually with CAMHS – Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.’

‘Yes, she’s mentioned it.’

‘I’ll do my best to get Jackson there.’

‘He needs something,’ Kayla said, dabbing her eyes. ‘I’m petrified he might do something silly and follow Connor.’

‘Has he told you he’s contemplated suicide?’ I asked, very concerned.

‘No, but I’ve lost one son that way – I know it’s possible – and Jackson was close to his brother, despite him being seven years older.’

‘You’ve told Frankie all of this?’

‘Yes.’

The door opened and Frankie returned. ‘Jackson is being looked after by a colleague,’ she said, and sat at the table. ‘I suggest we give him time to calm down, and then, when we’ve finished, he can go straight home with Cathy.’

Clearly arrangements had changed.

‘I haven’t brought any of his things with me,’ Kayla said. ‘I thought I’d have time to go home first.’ Then to me she said: ‘Jackson was supposed to be with my daughters, but he kicked off so badly I had to bring him with me.’

‘As Jackson is finding this all very difficult, I think it’s better he goes with Cathy now,’ Frankie said. ‘I can take you home so you can gather together what he needs for the next few days, then I’ll drop it off at Cathy’s later. Is that OK?’

Kayla nodded.

‘I’ve got spare clothes that will fit him,’ I said, ‘but obviously it’s better if Jackson can have his own. What’s happening about contact?’

‘I’d like to see him for a while every day,’ Kayla said.

I doubted this would be practical. ‘School returns next week,’ I pointed out, and I looked at Frankie.

‘Jackson will need time to settle in at Cathy’s,’ she said gently to Kayla. ‘And he’ll have school work to do. I suggest, to begin with, you see him for an hour after school on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and two hours at the weekend. Then we can review arrangements in a month or so.’

‘All right,’ Kayla said quietly. I made a note of the days.

‘Where is Jackson seeing his family?’ I asked.

‘At his home,’ Frankie said. ‘You will be able to take and collect him?’

‘Yes.’ The foster carer usually takes the child to and from contact as well as doing the school run. Carers who don’t drive use public transport or cabs. In exceptional circumstances the social services provide transport.

‘Will he be going to see his family straight after school?’ I asked. This was what usually happened.

‘Does that suit you?’ Frankie asked Kayla.

‘Yes.’

‘I’m guessing we’ll arrive around four o’clock,’ I said. Jackson’s home address and that of his school were on the placement information forms, so I knew the travelling time involved. ‘I’ll return to collect him at five?’ I clarified.

‘Yes, please,’ Frankie said.

‘And contact at the weekend?’ I asked. ‘Which day?’

‘Saturday, please,’ Kayla said. ‘He can come for lunch, but he can stay as long as he likes.’ I thought Kayla was now feeling guilty for placing her son in care.

‘I think we need to firm up a time for the weekend visit,’ Frankie sensibly said, ‘so Cathy knows when to collect him. Shall we say twelve till two?’

Kayla agreed. ‘But he can phone me any time,’ she said. ‘I’ve put credit on his phone.’

‘Perhaps you could phone on those days you’re not seeing each other?’ Frankie suggested. Although in practice, once a child has a mobile phone, this type of contact is virtually impossible to control. It’s not such a worry in cases like this where there are no safeguarding concerns (as far as we knew), but I knew of instances where a child was removed from home as a result of parental abuse and the parents continued to threaten the child over the phone, until the foster carer found out and reported it to the social worker and took away the phone.

‘Is there a parental control app on his phone?’ I now asked.

‘Yes,’ Kayla replied. ‘Connor set it up not long before he died. Connor always looked out for his young brother. He felt Jackson was too young to have a phone, as he’d had to wait until he was twelve.’ She smiled reflectively and I saw her eyes well up again.

With nothing further to discuss, Frankie suggested we go to collect Jackson; Kayla would then say goodbye and he would come home with me. I wasn’t expecting it to go smoothly and I was right.