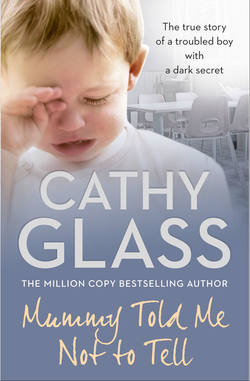

Читать книгу Mummy Told Me Not to Tell: The true story of a troubled boy with a dark secret - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 11

Chapter Five Safer Caring

ОглавлениеI went to bed early that first night, at ten o’clock, expecting to have a very broken night’s sleep; children, unsurprisingly, are often unsettled for the first few nights, in a strange bed and a new house. But Reece must have been exhausted, for I wasn’t woken until five o’clock. Then it was with a vengeance!

I was just starting to surface, with my eyes flickering open, when I heard Reece’s door fly open with a loud bang, followed by the sound of Reece in full flight. His feet thumped along the landing and he was making a high-pitched yeooowing noise, banging on the walls and bedroom doors as he went. He had done a full circuit of the landing and was on his way downstairs before I was out of bed. I threw on my dressing gown and went after him. Apart from stopping him from waking the girls (if they hadn’t already been woken), I needed to start to get him into the routine of staying in his bedroom and amusing himself until I was up and dressed.

I caught up with Reece downstairs, where he was trying to get into the living room, which I locked at night for security. ‘Reece,’ I said over the noise of his yeooowing. ‘Reece, sshhh, quietly, love.’ I placed my forefinger to my lips and, with my other hand lightly on his shoulder, turned him to face me.

‘Yeooooow,’ he went at the top of his voice.

‘Ssshh,’ I said again.

‘Yeoooow,’ he continued. Then, bringing his chin down towards his shoulder, he tried to bite my hand.

‘No,’ I said firmly. ‘No, you mustn’t bite. It’s naughty.’ He snapped again at my hand, which was safely out of reach. ‘No, Reece, don’t bite.’

‘I can bite, I’m Sharky.’ Which I had guessed and ignored. ‘Want to get in here,’ he said and, pulling away from me, he thumped on the living-room door with his fist.

‘No, Reece,’ I said. ‘Now quietly. We are going back to your bedroom, where you can play until it’s time to go downstairs. It’s too early. It’s not morning yet.’ I knew there was no point in suggesting he went back to sleep, as he had clearly had enough sleep and was now completely recovered from the previous day’s exhaustion.

He thumped on the living-room door again; then, with his mouth wide open, he tried to sink his teeth into the metal doorknob. The resulting sound of his teeth on metal set my own teeth on edge, and I thought it would do nothing for the enamel on his.

‘No, Reece,’ I said. ‘Don’t do that. You’ll hurt yourself. Come back to your bedroom.’

He turned and, breaking free from my light hold on his shoulder, was off down the hall, and then up the stairs. I caught up with him on the landing and, taking him by the arm, went with him into his bedroom, where I closed the door.

‘Yeoooow! Crunch!’ He went at the top of his voice. ‘Yeooow! I’m Sharky.’

There was a great temptation to say, ‘Well, Sharky had better play quietly with his toys,’ but I didn’t. ‘Reece,’ I said, again taking him by the shoulder and trying to get him to look at me. ‘Reece, I need you to be quiet, love.’

‘Yeck! Yeck! Crunch!’ he went.

Not letting go of his arm, I took the lid off one of the toy boxes and drew him down, so that we were both sitting on the floor. ‘Here, look at all these lovely toys. Let’s play with them,’ I encouraged.

Reece pulled in his cheeks to make his mouth narrow, which highlighted his front teeth. He then began making loud sucking noises, which I guessed were supposed to be an impression of a shark. I ignored it and continued sifting through the toys, hoping to gain his attention.

Half an hour later I was still there, seated on the floor of Reece’s bedroom in my dressing gown and trying to engage him in the toys and books. Reece whooped and yelped, snapped his jaws at invisible passing fish and every so often tried to jump on the bed or leave his room. It was imperative that I kept going until I had achieved what I had set out to: Reece remaining in his room and playing until I had washed and dressed and was ready to go downstairs. If I gave in now, it would set a precedent for all the future mornings and would be harder to change at a later date. As with so many behaviour issues, retraining relies on consistent and firm boundaries — i.e. endless repetition of the expected behaviour.

‘I need you to play in your bedroom until I say it is time to get dressed,’ I said over and over again, while picking out another toy or book, or starting a jigsaw.

Eventually, after another fifteen minutes, when Reece was probably as bored as I was with the sound of my voice repeatedly saying the same thing, he started to dive into the box of small McDonald’s toys of his own accord and began playing with them. I stayed for another five minutes, and then said: ‘Good boy. Now you carry on playing while I get dressed.’ I came out and closed the door.

I waited on the landing. A minute later Reece flung open his bedroom door and was about to zoom off again. I lightly caught hold of his arm and led him back into his room, where I resettled him with the toys. I told him again what I wanted him to do — to play quietly while I got dressed – and I came out and closed the door.

I waited on the landing and a minute later Reece appeared again in what I took to be full shark attack, snapping and yelping at the top of his voice. Again I returned him to the toys in his bedroom and, restating what I wanted him to do, came out. He reappeared and I resettled him, time and time again, doing what I had anticipated having to do the night before when I’d put him to bed.

Finally at 6.30 a.m., an hour and a half after Reece had first woken and got out of bed, he was playing with his toys in his bedroom, and I had the time I needed to shower and dress. He wasn’t particularly quiet — he was making noises which sounded as though they could be part of the pretend play – but at least he was doing what I’d asked. I knew I would probably have to repeat the resettling process every morning for a week or more, but the investment of time and effort now would reap rewards later, when Reece would wake and automatically play with his toys until I told him it was time for him to dress and come down for breakfast.

It was Friday, and a school day, so I woke the girls at seven (being teenagers, they had managed to go back to sleep despite all Reece’s noise). Then I knocked on Reece’s door and went in. He was seated, as I had last left him, cross-legged on the floor, now surrounded by the entire contents of both toy boxes. I told him he was a good boy for playing nicely in his room; then I said that although it was still early, he could get dressed and come down if he wanted to, or he could stay and play with his toys.

‘Telly?’ he asked. I hesitated. I wasn’t sure I wanted him watching television at this time in the morning. It could become a habit, which certainly couldn’t continue when he started school.

‘OK, but only for a little while.’ I switched on the television and found some children’s programmes on BBC2 which Reece recognized, presumably from having watched the series before. He immediately fell quiet, completely transfixed and absorbed by the screen. I could see only too clearly the great temptation of leaving Reece in front of a television for longer periods than were good for him.

Half an hour later, with the girls washed, dressed and having had their breakfasts, I knocked on Reece’s bedroom door and went in. He was, as I suspected he would be, still seated in the same position on the beanbag and riveted to the children’s programmes.

‘Good boy, Reece,’ I said. ‘I want you to switch off the television now, get dressed and come down for breakfast.’

He didn’t answer, so I repeated the instructions; then, taking out clean clothes from his wardrobe, I repeated the instructions again. He still didn’t answer, so I explained again what I wanted him to do. Then I switched off the television. As soon as the screen went blank Reece jumped up from the beanbag and began stamping on the piles of small toys that littered the entire floor.

‘No, Reece,’ I said. ‘You will break them.’ I knelt down and, taking him gently by the arm, drew him down beside me. ‘The first thing we are going to do is put these toys back into their boxes so they don’t get broken,’ I said, and I began putting them away. Reece was beside me watching. Then as I leant forward to retrieve another toy, hoping he would follow suit, he cuffed the back of my head with his open hand. ‘No, Reece,’ I said. I took hold of his hand and directed it again to the toys on the floor.

‘Want me breakfast now!’ he yelled.

‘You will have breakfast as soon as we have cleared away and got you dressed,’ I said.

‘Want it now,’ he yelled and went to cuff my head again. I took his hand and drew it once more towards the toys.

‘You will have breakfast as soon as we have cleared up and got you dressed,’ I repeated.

Eventually he realized I wasn’t going to give in and that if he helped me to clear away it would complete the task and get him what he wanted that much quicker. Suddenly he started grabbing handfuls of toys and throwing them into the boxes, so that very soon the floor was clear.

‘Well done,’ I said. ‘Excellent! Now get dressed. Then we can have breakfast.’

I had already taken out clean joggers, sweatshirt, vest, pants and socks, and placed them on the chair ready for him to dress himself.

Reece looked at them. ‘No!’ he yelled. ‘Can’t!’ which I had more or less guessed.

‘All right, I’ll teach you how to dress yourself, and won’t you feel good when you can?’ I smiled bravely, knowing that achieving this task was probably going to be no easier than the last of clearing away his toys, or any other task, come to that. It seemed that Reece was so used to not doing things, either because he couldn’t or didn’t want to, that his first response to any request was either ‘can’t’ or ‘won’t’.

‘No,’ he yelled again. ‘Can’t!’

‘I’m sure you can,’ I said evenly. ‘You are very clever. And, Reece, try not to shout, love. I can hear you just as well when you talk quietly. OK, love?’ There were so many issues with Reece that I was having to address them one at a time. Certainly, while the continuous shouting, or rather ‘voice modulation’ as it’s correctly termed, needed to be addressed, it wasn’t as much of a priority as his biting, head-butting or running berserk around the house.

‘Now, take off you pyjama bottoms,’ I encouraged, ‘and put on your pants.’ I held up his pants ready, but he stood helplessly waiting for me to do it.

‘Can’t,’ he said with slightly less volume, now sulking.

‘Try,’ I said. ‘I’m sure you can.’

‘Can’t,’ he said again and made no attempt. ‘You do it, cow!’

‘Reece,’ I cautioned, ‘please don’t use that word. It’s rude.’

‘Cow,’ he said again. He crossed his arms and stood glaring at me defiantly.

I remained where I was, a short way in front of him, still holding his pants. ‘Take off your pyjama bottoms and put on your pants.’ I repeated. ‘Do you want me to leave the room while you do it?’ I didn’t think it was modesty that was stopping him, for he hadn’t been self-conscious at bath time the night before.

He shook his head. There was an impasse for a good two minutes when Reece continued with his arms folded and glowered at me menacingly, while I stood relaxed and outwardly at ease, holding his pants out ready for him, as though waiting for Reece to get dressed was of no great importance and I had all the time in the world. For as the evening before when I had wanted him to go for a walk, if he saw my request was important to me, his refusal could easily become a tool for trying to manipulate me. But I had already been there, done that and ‘got the T-shirt’ many years ago when I had first started fostering. Eventually Reece would do as I asked and see that if he cooperated he would win my approval and feel happier in himself, but not yet. Now he hated me and wanted to do exactly what he had always done, which appeared to be nothing, or exactly what he felt like doing.

Five minutes later Reece pulled roughly on his pyjama bottoms and then, using his feet, stamped them to the floor.

‘Well done,’ I said, ‘although next time it might be easier to use your hands.’ He snatched the pants from me and, sitting on the bed, put them on without too much trouble.

‘Good,’ I said. ‘Now take off your pyjama top and put on your vest.’

He had real problems trying to get his arms out of his pyjama top, so I helped him, showing him how to do it, and then gave him his vest, which he got into first time. Next I helped him on with his sweatshirt.

‘Excellent,’ I said. ‘Now the socks.’

Aware that putting on socks is difficult for young children, particularly those with poor coordination, I told him to sit on the bed again and I would show him how to put on one sock and he could do the other.

As I knelt in front of him, he tried to cuff me over the head again and I guessed this regular cuffing had probably been done to him. ‘No, you don’t do that,’ I said, moving my head out of reach. ‘Do you understand?’

He nodded. I showed him how to put on one sock and passed him the other. ‘Who used to dress you before?’ I asked casually as he struggled to get his toes into the sock.

‘Carers.’

‘And at home?’

‘Don’t know.’

He had made a reasonable attempt at putting on the second sock and I helped him to complete the task. Praising him, I took his hand and we went downstairs together. Lucy and Paula were in the hall, putting on their coats, ready to leave for school and college. I hadn’t seen them properly that morning because I had been so occupied with seeing to Reece.

‘Bye, loves,’ I said. ‘Have a good day.’ I kissed them both.

Reece pursed his lips, wanting to kiss them goodbye also. Lucy and Paula smiled and, bending towards him, offered their cheeks. He gave them a nice little kiss each.

‘Goodbye,’ they both called to us. I saw them out and closed the door. Reece was beside me, his hand still in mine.

‘Cor, that was nice,’ he said, grinning. ‘I’d really like to give them one.’

I paused in the hall and looked at him, my heart sinking. ‘Pardon, Reece? What did you say?’

He grinned again, leering almost. ‘I want to give them one,’ he repeated. He dropped my hand and clamping his left hand on to his right arm he brought up his fist in the crude pumping gesture of wanting sex.

‘I’m not sure what you mean,’ I said, knowing only too well. ‘But it’s not a nice thing for a boy of seven to say. And please don’t do that with your arm.’

‘My dad does to my sister,’ he said and stopped, aware that he had committed the ultimate sin of saying something about home.

‘Does he?’ I asked lightly, while assured of Reece’s reply.

‘Don’t know. I want me breakfast now. You said it was time.’

I followed Reece into the annexe off the kitchen, which we call the breakfast room. I knew from Reece’s history he’d seen a lot of inappropriate behaviour, possibly even sexual abuse, but I was still shocked and saddened. I also knew that Reece had been sworn to secrecy and wasn’t about to say anything more. Later I would talk to the girls and remind them of our ‘safer caring policy’ — the guidelines all carers follow. They had just left with Reece giving them a kiss on the cheek like any younger brother, but Reece had laden it with sexual connotations and for all our safety we were going to have to be very careful.

The ‘safer caring policy’ is a document drawn up by all foster carers detailing how they keep everyone in the household safe. It is not just about strapping children under seatbelts in the car or making sure there are batteries in the smoke alarms. It is also about how we treat foster children who have come from inappropriately sexual explicit homes, or have been sexually abused, and have therefore developed feelings and attitudes that are inappropriate and beyond their age. I knew already from what Karen had told me on the phone that there was a suggestion that Reece’s father had sexually assaulted Reece’s half-sister, and that a paedophile had been going into the family home. What I didn’t know, and what the social worker, Jamey Hogg, would I hoped tell me when he returned from holiday, was whether Reece had witnessed or been included in any paedophile activity in the home. I also knew that Reece had been allowed to watch adult videos, which could account in some way for his viewing the girls in sexual terms, but without further details we would have to assume the worst and act accordingly. For if Reece did view Lucy and Paula as objects of sexual desire instead of older sisters, as his comment had suggested, then his behaviour would reflect that. Not only would it be very unpleasant for the girls but it could easily lead to Reece interpreting any affection from the girls towards him in sexualized terms. The whole subject of sexual abuse is sickening and sad but it is something that has to be dealt with by foster carers all too regularly.

Although I had written up my daily log notes the night before, detailing Reece’s first day with us, I had been too tired to look at the placement forms. Now I wondered if they contained any more information on Reece’s background that I should be aware of. Settling Reece at the table with the two slices of toast and jam he had asked for, I quickly went into the front room, unlocked my desk and took out the placement forms; then I returned to sit opposite him at the table. I read as Reece ate, eating being another activity that appeared to keep him quiet for its duration.

As I turned the pages of the placement forms, I saw there was nothing on his background beyond what I already knew, apart from Reece’s parents’ address, which came as something of a surprise. His parents lived in a flat on an estate no more than half a mile away. I hoped the social services had noted this, for it was a little too close for comfort, given that his parents wouldn’t be told our address. It was quite possible that we used the same high-street shops, which meant there was a risk of us bumping into each other. Not a problem if the child’s parents were cooperating with the social services, and were allowed to know where the child was, but clearly that wasn’t the case with Reece. I’d had experience of ‘impromptu’ contact before — in the shops or outside the school gates – and it’s a difficult and embarrassing situation for all, not to mention intimidating if the parents are angry and blame the foster carer. I would mention my concerns and Reece’s attitude to the girls to Jill when she phoned again — not that I thought for one moment the social services would move Reece because of where his parents lived, but it was something they needed to be aware of, if they weren’t already.

I returned the placement forms to my desk as Reece finished his breakfast. Although he had been focused and concentrating while eating, as soon as he’d finished he was out of his seat, zooming around and streaking jammy fingers along the walls.

‘Come on, Reece,’ I said. ‘We’ll give you a wash and do your teeth; then we’re going out in the car.’

The mention of the car seemed to please him, because he ran straight up the stairs and into the bathroom, with his arms outstretched and yelping at the top of his voice. I showed him how to squirt toothpaste on to his toothbrush and watched as he made a good attempt at brushing his teeth; then I ran warm water into the sink and, wringing out his face flannel, helped him to wash his face. I asked him if he needed the toilet before we went out, and he said he didn’t. I took his hand and we went downstairs and into the hall, where I passed him his coat and shoes. He made a good attempt at putting them on and I was pleased he hadn’t just stood there helplessly as he had done the night before – this was already a small improvement and I praised him immensely.

I assumed Jill would be phoning at some point during the day, so before going out I switched on the answer-phone and dropped my mobile in my handbag. It took me some while to settle Reece on the booster seat under his belt in the rear of the car; he didn’t appear familiar with the procedure, which was surprising given that yesterday he’d said he was used to being in a car rather than walking. First he wanted to ride in the front passenger seat, which I explained wasn’t legal at his age; then he didn’t want to sit on the booster seat, which I explained was a legal requirement. I secured his seat-belt over his shoulder, but he kept tucking it under his arm, which would have not only rendered it useless in an accident but also badly hurt his stomach if it had suddenly tightened.

Fifteen minutes later I reversed out of the drive with Reece making brumm-brumm noises at the top of his voice. I stood it for as long I could, for I realized he was only doing what a lot of boys do, imitating the car engine noise, but very loudly.

Then I said, ‘Reece, I need you to be quiet in the car so I can concentrate on driving.’

‘Brummmm! Brummmm!’ he yelled, louder.

‘Would you like some music on?’ I asked. ‘I have a sing-a-long CD here.’ Although Reece’s singing would doubtless break the sound barrier (everything he did was at such a volume) it would be preferable to the exploding sound of his brumms, which were making me jump each and every time they erupted.

‘Brummm! Brummm!’ Reece yelled, his lips trembling with the vibration of the brummm. I inserted the CD in the hope he might join in, but five minutes later, when the brummms had increased in volume and intensity and were drowning out the sound of ‘The Wheels On The Bus’, I switched it off again.

‘Reece, you will have to try and sit quietly,’ I said. ‘I can’t concentrate on driving when there is a lot of noise.’

‘Bruummm! Bruumm!’ Then, ‘Yeoooo crunch crunch,’ which I wasn’t sure represented a car, a plane or even a shark attack, but whatever it was the noise was deafening. Then he started kicking the back of the passenger seat.

I indicated, and drew into the kerb. Putting the car into neutral and the handbrake on, I turned in my seat to look at Reece. He was now yelping and kicking the seat in a frenzy.

‘Reece!’ I said. ‘Reece, listen to me.’

He didn’t.

‘Reece, I need you to be quiet and sit still.’ I tried again, raising my voice so it could be heard over the relentless yelps. ‘Reece, quiet, and please stop kicking that seat. We don’t kick anything other than footballs.’

He didn’t stop, so I switched off the engine, got out and went round to the pavement and opened his door.

‘Reece,’ I said firmly. ‘Sit still. Now, please!’ I placed my hand lightly on his legs to quell the kicking. ‘Sit still and be quiet. Then we can go to the supermarket and you can push the trolley.’

He continued with the yelping and kicking for another few seconds; then suddenly he stopped the noise and became still.

‘Can I?’ he said, looking at me suspiciously. ‘Can I push the trolley?’

‘Yes,’ I said, smiling. ‘Would you like to help?’

He nodded furiously, his head bobbing up and down. All Reece’s movements were accentuated when he was in a hyperactive state. ‘I’ve never pushed a trolley before,’ he said. ‘Can I really push it?’

I smiled sadly. The poor kid: while he had been party to goodness knows what in the adult world at home he had missed out on the simple childhood pleasure of pushing a supermarket trolley and helping mum to shop.

‘All right, Reece, now listen to me,’ I said, looking at him carefully. ‘You can push the trolley as long as you sit quietly while I drive to the supermarket. OK?’ It wasn’t bribery, just positive reward for good behaviour, and he nodded furiously. I returned to the driver’s seat and drove to the supermarket at the edge of town with no more than a ‘wow’ when I had to brake quickly as the car in front suddenly pulled into the kerb without signalling. And I thought that pushing the trolley was going to be another strategy for encouraging Reece’s good behaviour, so that together with reading a lot of books I was also going to be doing a lot of shopping, which was fine because we consumed a lot of food.

Reece pushed the trolley remarkably well, controlling the speed to an acceptable 5mph, once I’d explained there were elderly people in the store who couldn’t get out of the way in time if he went any faster or tried to run them over. Reece’s biggest problem in the supermarket was curtailing his enthusiasm. I had asked him, as I ask all foster children, to choose some of his favourite food. We already had Chicken Dippers, tinned spaghetti hoops and Wall’s sausages in the trolley in abundance, but would also have had, had I not returned them, five cartons of chocolate ice-cream (I kept one), six packets of Jammie Dodger biscuits (I kept two) and twelve tubes of brightly coloured sweets (I put them all back because of the additives and replaced them with milk chocolate bars). I praised Reece for the way he steered the trolley and helped me, and he glowed from achieving the task successfully. He was also pretty patient at the checkout, considering the length of the queue, and I only had to remind him a couple of times not to shunt the trolley into the back of the man in front.

Once it was our turn at the checkout Reece’s enthusiasm for shifting all the food from the trolley on to the belt knew no bounds. The items were jettisoned with such force that they found their way to the cashier without the need of the moving belt. I held back the box of eggs and put them on myself. I paid, and then Reece helped me push the trolley out of the store and through the car park, missing most of the cars. I strapped him into his seat while I packed the bags in the boot — it was safer than having him hopping around in the car park. Once all the shopping was in the boot I returned the empty trolley to the trolley park close by and got into the car. Before inserting the keys into the ignition I turned and looked at him. ‘Good boy,’ I said. ‘Thanks for helping me.’ Then I noticed he was chewing something.

‘What are you eating?’ I asked, for certainly I hadn’t given him anything. I had said he could have one of the iced buns when we got home.

‘Sweets,’ he said, producing a packet of fruit pastels from his coat pocket.

‘Where did you get those?’

‘From the shop.’

I stared horrified. ‘But I didn’t buy them.’

‘No, I looked them,’ he said, popping another one into his mouth.

‘But Reece, that’s stealing. I didn’t pay for them.’

He gave a shrug. ‘No worries. The police can’t do me. I’m under age.’

I stared at him, dumbfounded, as he chewed loudly, unashamed by his admission. Clearly Reece had no idea that stealing was wrong but was well aware he was below the age of criminal responsibility and therefore couldn’t be prosecuted even if he was caught.

‘Who told you that?’ I asked.

He shrugged. ‘Don’t know.’ So I could guess.

‘Did you use to steal things when you lived at home?’

He didn’t say anything, but popped another pastel in his mouth and grinned. I certainly couldn’t let him enjoy the spoils of his theft. I opened my door and got out. I went round to his door.

‘Reece,’ I said leaning in and taking the pastels. ‘You have taken these without paying for them, so they are not yours. It’s stealing. We have to pay for the things we want: we don’t just take them.’

‘But they’re mine!’ he yelled, making a grab for them.

‘No. They are not, Reece. They belong to the shop. They only become ours if we pay for them.’

If the item had been of any greater value I would have taken it back to the store, but returning a half-eaten tube of fruit pastels was going to cause more trouble than it was worth, particularly as I would have to take Reece with me and he was now erupting with force.

‘Mine!’ he yelled, kicking the back of the seat in a frenzy. ‘Mine! Give me them! Thief!’ which I thought was choice.

‘No, Reece. You won’t have these sweets. They are not yours, they are the shop’s.’ I dropped them into my coat pocket to throw away later.

‘Mine,’ he screamed. ‘Mum gives me the sweets when I help her.’

‘Help her do what?’ I asked over the noise.

‘Take things,’ he said. Then he stopped.

‘You stole things for your mum?’

He stopped screaming and looked at me. ‘Hate you,’ he said and poked out his tongue, which was bright green from the pastels.

The return journey from the supermarket was more eventful than the one going when Reece had sat quietly in his seat with the promise of pushing the trolley. Now he screamed, yelled he hated me and kicked the seat relentlessly. I had to stop three times to resettle him and return him to under his seatbelt. After repeated warnings, I told him he had lost thirty minutes’ television time that evening because I couldn’t have him distracting me while driving, as it was dangerous.

‘I’m watching television,’ he yelled defiantly as we finally entered the house.

‘No, you are not, Reece. You can help me to unload the car or you can play with some toys.’

‘I’m watching telly,’ he yelled again, sticking out his tongue.

I ignored it and began unloading the car with the front gate bolted so that he couldn’t run out into the road if he had a mind to. Each time I carried the bags of shopping into the house I checked on where he was and what he was doing, which was zooming around, arms outstretched and making whooping noises, so at least I knew where he was.

Once I had all the bags in the hall I began carrying them through to the kitchen. ‘Would you like to help me?’ I called to Reece, but he was in no mood for cooperating. By the time I had all the bags in the kitchen Reece had done a dozen laps of the house and was demanding lunch.

‘You can have lunch, yes,’ I said, glancing at the clock. ‘It’s twelve o’clock. But say “Can I have lunch?” rather than “Give me”. Sit at the table and I’ll make you a sandwich.’

The promise of food settled Reece and I quickly made a ham sandwich, which he ate while I unpacked the food into the cupboards and fridge-freezer. As soon as he’d finished he was out of his seat and orchestrating one of his plane landings or shark attacks. I made a hasty sandwich for myself, took it into the living room and ate it while reading Reece some stories. He was quiet again and the incident of the sweets had now been forgotten. I wouldn’t say anything more about them now, but next time we went shopping I would remind him that things in the shops only became ours when we paid for them.

Sadly, Reece wasn’t the first child I had come across whose parents had primed their child to thieve as though they were modern-day equivalents of Fagin. Sometimes it had been out of necessity — there was no food in the house and the benefit money wasn’t due until the following week. Sometimes it had been for more expensive items like iPods, jewellery and CDs, where the easiest option was to take the item rather than save up for it as socialized parents teach their children to do. I didn’t know enough of Reece’s home situation to know whether it was from necessity or greed he had been trained to steal and then rewarded with sweets, but clearly I would have to be more alert in future, because I still had absolutely no idea when he had slipped the sweets into his coat pocket. His technique had clearly been well designed and I suspected well practised.

The afternoon passed with me reading Reece more books and then with me beside him, painting and Play-Doh. This was interspersed with him zooming around when there was a break in the activity. Reece repeatedly asked if he could have his television on and I repeatedly explained that he had lost half an hour of his television time for his behaviour in the car, and that he could have it on at four o’clock instead of 3.30 when the pre-school programmes began.

When Lucy and Paula returned, I briefly took them aside and, having asked them how their day had gone, told them of Reece’s comment that morning after he’d kissed them goodbye. I didn’t need to say anything more: they knew the implications of having a sexually aware child in the house, and they also knew the guidelines we all had to follow. We followed the ‘safer caring’ guidelines anyway, with any fostered child, but if there were issues over possible sexual abuse or even inappropriate television watching which had made the child sexually aware, we were even more careful. So, for example, bedtime stories were read downstairs, not in the child’s bedroom, and kisses and cuddles were given downstairs, with the child at our side, not on our laps or face to face. It’s sad, really, because we naturally hug and kiss our own children without a second thought, but with a child who has been sexually abused, or has come from a highly sexualized and inappropriate home life, even the most innocent of hugs or kisses (like those the girls had allowed Reece that morning) can be misinterpreted. Reece would still be having his hugs and kisses — he was after all a little seven-year-old — but there would always be someone else present and we would be just that bit more careful so that nothing could be misconstrued by him.

Jill phoned just after 5.00 p.m. and I updated her, and before I went to bed I wrote up my log notes. That night I lay in bed contemplating and worrying over the day’s events, and I wondered how well I had handled everything that had happened — from Reece’s hyperactive behaviour, to the stealing, and of course his comments about giving the girls one. Foster carers are plagued by analysing and self-doubt, even more so than when raising one’s own children; for when all is said and done what greater responsibility is there than bringing up someone else’s child?