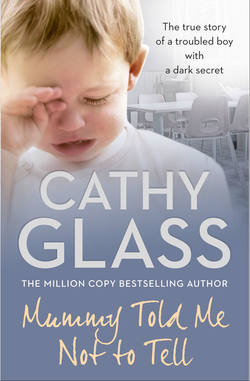

Читать книгу Mummy Told Me Not to Tell: The true story of a troubled boy with a dark secret - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 9

Chapter Three Sharky

ОглавлениеJill phoned at just gone 11.00 the following morning and I felt my stomach tighten. I’d had a night to sleep (or rather not sleep) on all that I’d heard about Reece and, despite years of fostering, my nerves were starting to get the better of me. Supposing his behaviour was as bad as had been reported and I wasn’t able to help him? Supposing this was the one child I had to give up on? I pulled away from that thought.

‘A male social worker, Imran, will be bringing Reece,’ Jill said. ‘At about one thirty. I’ll aim to be with you half an hour before — at about one.’ Jill tried to be with me when a child was placed, partly to make sure the paperwork was all correct and also for a bit of moral support.

‘OK. Thanks,’ I said.

And I believe Karen phoned you yesterday.’

‘Yes, she was very helpful.’

‘Good. She worked with Reece’s family for a while. It’s a pity she’s not still on the case. She’s very practical and down to earth.’

‘Yes.’

We said goodbye and I returned upstairs, where I was putting the finishing touches to what would soon be Reece’s room. With Lucy and Paula at school and college, and Adrian away at university, I was alone in the house and it seemed very quiet. Not for long, I thought. In a couple of hours I’d have Reece to entertain me! I finished putting the Batman duvet cover and matching pillowcase on the bed, and then I glanced around the room. I hoped Reece would like it. I’d put posters of Star Wars on the walls, and jigsaws and puzzles in the toy box; and, mindful that Reece was functioning at a much younger age, I’d included a poster of Winnie-the-Pooh, two soft cuddly toys and a wizard castle with play people.

I always try to make the child’s bedroom suitable for their age and gender, with things that are likely to appeal, based on the information I have on the child. If the child comes with a lot of their own personal possessions, then I pack away what they don’t want of my things and put up theirs instead. It’s so important for the child to have their possessions around them: it helps them to settle and makes them feel secure.

As I had been doing respite fostering for three months, the theme in the room had changed repeatedly and as a result there were little nests of drawing-pin holes where posters and pictures had been up and down. I’d filled them with a quick coat of paint, a pot of emulsion being another essential tool for good fostering.

At twelve noon I was about to have a bite of lunch when the phone rang. It was Jill.

‘Sorry, Cathy, will you be able to manage alone this afternoon? I’ve been called into our south county office. One of the workers has gone home sick.’

‘Yes, don’t worry. I’ll be fine.’

‘Phone my mobile if you need anything. Otherwise I’ll phone you later after Reece is placed.’

‘All right, Jill.’

Jill being unable to attend when a child was placed had happened before and I wasn’t unduly concerned. I’d been fostering long enough to know the procedure and Jill knew that. Had I been new to fostering another worker from Homefinders would have come in her place, but I could cope — so I thought!

By 1.30 I was as prepared as I was going to be for Reece’s arrival. I wandered in and out of the front room, glancing up and down the street from behind the net curtains. Nerves were starting to get the better of me again, and I wished Reece had arrived as an emergency placement as Sam (and others before him had done); then I wouldn’t have had this build-up. But I reminded myself that if I was feeling anxious, goodness knows what Reece must be feeling, on his way to his fifth new home in six weeks.

At just after two o’clock, when there was still no sign of Reece, I began thinking about giving Jill a ring to make sure everything was going according to plan. I gave one final glance through the front room window and as I did a silver car drove up and stopped outside the house. I looked out from my vantage point behind the nets and saw a boy who’d been in the rear of the car scramble over the top of the passenger seat, fling open the passenger door and leap out on to the pavement. Aged about seven, heavily built with a shaved head, he began jumping up and down, yelling at the top of his voice: ‘Beat you! Beat you out! Beat you out the car, slag!’

Reece had arrived.

As I watched, a woman, who I assumed must be a social worker, jumped out of the driver’s seat, ran on to the pavement and grabbed his hand. ‘Don’t do that!’ she cried, anxiously. ‘It’s dangerous. You should have waited until I got out.’

Reece, oblivious to her caution, continued jumping up and down, still shouting: ‘Beat you! Beat you, slag!’ Then he tried to head-butt her. I flinched as he narrowly missed her nose.

I began towards the front door, making a mental note that when Reece was in my car I would have the central locking down, rather than just the child locks, until he learned to stay in his seat until I opened his door. I also made a mental note to keep my head up as I greeted Reece, for clearly head-butting was another of his accomplishments.

‘Hello,’ I said, smiling, as I opened the front door and they came down the path. ‘I’m Cathy, and you must be Reece?’

The social worker was holding Reece’s wrist to stop him from running off — he clearly didn’t want to hold her hand. As they came into the hall she transferred his arm to me and sighed.

‘Hello, Reece,’ I said, not bending to his height. He didn’t look at me but stared and then lunged down the hall. I kept hold of his arm and he pulled against me.

‘Leggo! Leggo of me,’ he yelled.

Placing my free hand on his shoulder, I tried to turn him round to face me so that I could make eye contact with him and gain his attention. ‘Reece, listen,’ I said, kindly but firmly. ‘Listen to me.’ He was still pulling and refusing to look in my direction. I didn’t want to bend forward to make eye contact, as that would leave me in exactly the right position for a well-aimed headbutt. ‘Reece, we are going down the hall now and into the back room. There are some toys there already set out for you.’

‘Leggo! Leggo of me!’ His voice was rasping, guttural, like an old man’s, and so loud it filled the air and obliterated any other sound.

‘OK. Let’s go down the hall together,’ I said calmly but firmly. I knew if I let go of him now in his heightened state of alert he would be off like a free radical, charging around the house, doing damage to himself and anything that got in his way. Later I’d show him round, but for now I just needed to get him calmer and establish some form of control.

With Reece still pulling against me — and he was very strong with his weight behind him — I began steadily, if not a little jerkily, down the hall and towards the back room, which is our living room.

‘I’m Veronica,’ the social worker called from behind me, closing the front door.

‘Nice to meet you,’ I returned over my shoulder.

‘Slag!’ Reece shouted.

Once we were in the living room I let go of Recce’s hand and closed the door. As I’d hoped he would, he went straight to the selection of games I’d arranged in the centre of the room; the rest of the toys were in cupboards in the conservatory that acts as a playroom.

Veronica sank gratefully on to the sofa, happy to transfer the responsibility for Reece to me, while I remained casually standing in front of the door. It wasn’t obvious to Reece, but I was blocking his exit in case his interest in the toys vanished and he made a dash for it.

‘Sorry we’re late,’ Veronica said. ‘Imran was supposed to bring Reece but it became impossible.’

I glanced at her questioningly as Reece continued overturning the toys, tipping them from their boxes but not actually playing with them. ‘Imran is Asian,’ she said, and then nodding at Reece, mouthed: ‘He’s racist.’ She looked anxiously from me to the framed photographs of my children on the walls, where there were some of my adopted daughter Lucy, who is part Thai.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘I’ll deal with it.’ For while some carers would refuse to look after a child who is deemed racist, I had found that children of Reece’s age will have learned such behaviour from home, and it can be unlearned pretty quickly. I was more concerned about Reece’s apparent ADHD (Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder), which hadn’t been mentioned by Jill or Karen but was very obvious now. His continual agitated and jerky movements, his short quick breaths as though he was hyperventilating and his heightened state of alert, which stopped him from focusing on anything for longer than a second, suggested hyperactivity. I needed to get him calmer before I could offer Veronica a coffee, let alone address the paperwork, which she was now taking from her briefcase.

Reece had finished turning out all the boxes of puzzles, jigsaws and toys, and they were now in a colourful mountain in the centre of the room. I slowly moved away from where I was standing by the living-room door and went over, squatting on the floor beside him.

‘Reece,’ I said, trying again to make eye contact, ‘choose a game for us to play with and we’ll put the rest away.’

He didn’t so much as glance in my direction. His brain seemed so busy firing off in random directions it had blocked out almost everything and everyone around him, or any logical thought. I lightly touched his hand and he glanced towards me, but I didn’t think he’d actually seen me. ‘Reece, shall we play with these building bricks?’ I suggested. ‘I bet you are good at building things.’ I put two pieces together but Reece was already on his feet, going straight over to the bookcase, where he began pulling books off the shelves. By the time I was at his side he had cleared one shelf and was starting on the next. ‘Reece, would you like me to read you a story?’ No reply, and no response, just more books thrown on the floor.

‘Right, Reece. Here’s a nice book,’ I said more loudly. I stooped and retrieved a large colourful counting book from the ever-increasing pile on the floor. ‘Let’s read this one. It’s a counting book, with lots of pictures, and all the numbers to a hundred. I wonder if you can count to ten?’

The books suddenly stopped raining down and he turned to look at me properly for the first time since arriving. I noticed what lovely brown eyes he had but what unusual front teeth. His front four teeth at the top were very large, overlapped each other and had prominent serrated edges. It crossed my mind whether this had contributed to the ‘Sharky’ tag his mother had given him, in which case it was unbelievably cruel.

‘Well?’ I said, making direct eye contact. ‘Can you count to ten, Reece?’

He grinned broadly, which highlighted even more the unusual configuration of his teeth. ‘Of course I can, you silly bugger!’ he said. ‘I can count to a hundred.’ He grabbed the book from my hand and, throwing himself on the sofa, sat expectantly, waiting for me to read. I wasn’t worried about being called a ‘silly bugger’ or his snatching the book, for at last he was calmer and I had his attention.

I sat beside him on the sofa as Veronica began sorting through her paperwork. Reece moved closer into my side and then placed the book in my lap. I opened it at the first page, which showed a huge three-dimensional number 1 on the left-hand page with a corresponding picture of one large white cuddly rabbit on the right-hand page.

‘So what is this number?’ I asked.

‘One!’he yelled.

‘Good. Well done. But there’s no need to shout. I’m sitting next to you.’ I turned the page to reveal a large three-dimensional number 2 and an accompanying picture of two rag dolls.

‘Two!’ Reece yelled.

Veronica now had the placement forms and relevant paperwork ready on her lap. Between turning the pages and reading the numbers I began answering her questions, first about my doctor’s contact details where I would register Reece, and then my mobile number, which the social services didn’t have.

‘I would offer to make you coffee,’ I said to her, ‘but I think it would be wise to keep this book going for a while.’

‘Absolutely,’ she said. I continued turning the pages as Reece shouted out the numbers, and Veronica asked questions and made notes. By the time Reece and I had arrived at number 15, Veronica had all the additional information she needed, and the placement agreement form was ready for me to sign. She leaned forward and passed me her pen and the form. I signed with my right hand, while turning the page of the book with my left. Veronica separated the copies and put one copy on the coffee table for me.

‘I would normally go through the essential information forms with you,’ she said, glancing at Reece, ‘but I’m not sure that’s a good idea at present.’ The essential information forms contained the full names, addresses and ages of the child’s immediate family, and details of his and their ethnicity, any religious, dietary or medical needs, the type of court order granted to bring the child into care and any special conditions the child had such as behavioural difficulties. ‘No,’ I agreed. I’ll look at it later when I have the opportunity.’ I turned the page to the number 20 and a picture of twenty little elves.

‘I don’t think it contains any more than you’ve already been told,’ Veronica said. ‘The contact arrangements haven’t been finalized yet.’

I glanced up from number 24, which was twenty-four small white mice. ‘All right. Fine.’

Reece nudged me to continue, which I did. Then I paused and said: ‘Reece, you’ve been a very good boy. You’ve sat here very nicely. I’m so pleased you like books, because I do too.’ Number 25 was twenty-five red tulips. Reece yelled out the number and I turned the page again.

‘Well, unless there is anything else you can think of, I’ll leave you to it,’ Veronica said, placing the set of essential information forms on top of the placement forms.

I stopped turning the pages and looked at Reece, still calm beside me. ‘Reece,’ I said. ‘I will continue reading this in a minute after we have said goodbye to Veronica. All right?’

He jabbed the open page with his forefinger. ‘No, read!’ he demanded. ‘I want the book.’

‘Well, in that case, if you are not going to say goodbye, you can look at the book by yourself for a moment while I see Veronica to the door.’

I moved the book, now open at twenty-eight twinkling stars, from my lap to his and stood up. Reece immediately jumped up beside me, jettisoning the book on to the floor. ‘What about me fings?’ he yelled at the top of his voice. Veronica and I looked at each other and smiled. In all the kerfuffle of Reece’s arrival we had both forgotten about Reece’s belongings, which would be in Veronica’s car. Learning difficulties Reece might have, but he wasn’t going to be left without his possessions!

‘Well done,’ I said to him. ‘We can’t let Veronica go without giving us your things, can we?’

He grinned his toothy grin. ‘You silly buggers, you forgot!’ he shouted, giving me a hefty whack on the arm. He shot out of the living room and down the hall towards the front door. I went straight after him, leaving Veronica putting away her paperwork.

‘Reece, don’t open that door!’ I called.

He was already grappling with the front doorknob, which fortunately sticks, trying to turn it to get out and to the car for his belongings. I arrived beside him and gently put my hand over his on the doorknob. ‘There’s a busy road out there,’ I said. ‘You must always wait until I open the door. We don’t want you getting hurt.’

My left hand was lightly on top of Reece’s hand, and both of them were on the doorknob, which was level with his head. Before I realized what he was about to do he’d brought his mouth forward and sunk his teeth into the back of my hand.

‘Ow!’ I cried, and immediately withdrew my hand as Reece continued to yank on the door. I pressed my foot against the bottom of the door so it wouldn’t open and looked at the back of my hand. His front teeth were clearly imprinted in my flesh, but fortunately it wasn’t bleeding. I took hold of him lightly by the shoulders and, turning him away from the door and towards me, I tried to make eye contact.

‘Reece,’ I said firmly, ‘that was naughty. You don’t bite. It hurts. It’s not a nice thing to do.’ But his eyes were darting all over the place and I knew he couldn’t hear me even if he’d wanted to. ‘Reece,’ I said more loudly, still holding his shoulders, ‘Reece, look at me. You don’t bite.’ Still not looking at me, he brought his chin down on to his left shoulder and tried to bite my hand, which was resting there. Then he turned his head quickly and snapped at my other hand, but both were fortunately out of his range.

‘No!’ I said again. ‘Don’t bite. It’s cruel. You will stop that now!’

He snapped again at both my hands, and then wrenched free of my hold and charged up the staircase.

Veronica was beside me now. ‘Cathy, are you all right?’ she asked.

We both looked at my hand, which still bore the perfect impression of Reece’s front teeth.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘It hasn’t broken the skin.’ I glanced anxiously up the stairs. I could hear Reece charging around the landing. I certainly didn’t want him up there alone.

‘Veronica,’ I said. ‘Could you bring Reece’s belongings in from the car while I go up and settle him?’

‘Of course,’ she said. I quickly propped the door open so that she could get in and out, and then I went upstairs.

I found Reece in my bedroom, bouncing up and down on the bed for all he was worth. The springs bonged unhappily.

‘Off now!’ I said. He continued bouncing, turning away so that his back was towards me. ‘Reece! Get off that bed now!’

He ignored me, so I moved forward. I leant over the bed and, taking hold of him round the waist, I drew him down on to the bed and into a sitting position. I sat behind him and encircled him with my arms, with him facing away from me. My hands covered his and were out of reach of his teeth. He laughed at being held, and then struggled, laughing some more, before finally he gave up and relaxed.

‘Good. That’s better,’ I said. I held him for a moment longer; then I took my arms from around his waist and took hold of one of his hands. I led him off the bed. ‘Reece, this is my bedroom,’ I said. ‘It’s private. It’s just for me. You don’t come in here. I’ll show you your bedroom when we’ve said goodbye to Veronica.’

‘Want to see it now,’ he yelled.

‘And I want you to stop biting, Reece. Look at my hand.’

I raised the hand he had bitten to his line of vision while holding on to him with my other hand. Had I let go of him I had no doubt he would have shot off straight into another bedroom. ‘Look at those marks,’ I said, needing to make the point about biting. ‘Your teeth did that and it’s not good.’ In truth the physical damage was small, but biting is a nasty habit and I had to stop it straightaway. If he had broken the skin it would have been far more serious, for all types of infections including hepatitis and the HIV virus can be passed through blood drawn by a bite.

Reece now seemed to be focusing on my hand and I left it in his line of vision while remaining alert to any sign that he might strike again. ‘People don’t bite each other,’ I emphasized. ‘And you mustn’t.’

‘I’m not a people. I’m a shark,’ he said.

I turned him round to face me squarely, and searched again for eye contact. ‘Reece, you are not a shark. You are a little boy, and boys don’t bite.’

‘Yes, they do. I’m Sharky boy.’

‘You’re not Sharky. You are Reece and you will stop biting. Do you understand?’

He didn’t say anything and his eyes once again ran over the room, looking at everything except me.

‘Have I got a telly in me room?’ he asked suddenly.

‘Yes, you have. And it’s a special treat to have a television in your bedroom. As you can see, I haven’t got one in my bedroom.’ I would be using the television in his room — as I had with other children who liked television — as a reward for good behaviour and its removal as a sanction for bad behaviour. ‘OK, Reece,’ I said, taking his left hand in mine and leading him from my bedroom, ‘we’ll look at your room now and I’ll show you the television.’

Springing along beside me, with his hand in mine, we went round the landing and into his bedroom. I heard Veronica downstairs make another trip into the hall with Reece’s belongings.

‘I want it on now,’ he yelled, making a lunge for the remote control, which lay on top of the television.

I intercepted and took it. He glared at me. ‘Right, Reece,’ I said, trying to make eye contact again, ‘having a television in your bedroom is a very special treat. You will be allowed to watch it for short periods if you are good. Being good means not biting and doing what I ask you to. Do you understand?’

He nodded, and briefly looked in my direction.

‘Excellent. Now, you can sit on this beanbag, and I’ll see if there are any children’s programmes on.’ It was just after three o’clock, so I thought there would be. He did as I asked and sat on the beanbag. I turned on the portable television at the plug, and then flicked the remote until I came to a pre-school children’s cartoon.

The change in Reece’s behaviour was instant and dramatic. He was immediately transfixed, as he had been earlier by my reading a book. His limbs stopped their frantic and continuous twitching and his breathing regulated; all his attention was on the bright cartoon images chasing across the screen. Although his calmness was welcome, it was also odd because children with true ADHD often can’t relax even in front of a television. I could see that carefully controlled television watching together with story reading were going to be useful strategies in managing Reece’s behaviour. Leaving Reece on the beanbag, completely absorbed in the programme, I went downstairs to Veronica, who had just finished offloading Reece’s belongings into the hall. She was now waiting for me.

‘OK?’ she asked hopefully.

‘Yes. He’s watching children’s cartoons and is much quieter.’ I glanced at his luggage — a large suitcase, a couple of rucksacks and two toy boxes, which was about what I would have expected to come with a child who had been in care for just over a month.

‘Well, I hope you have a good evening,’ Veronica said. Then she took a folded piece of paper from her pocket and passed it to me. ‘His previous carer asked me to give you this. It’s the food he likes.’

I unfolded the paper and read: ‘Reece likes most things but his favourites are Chicken Dippers, fish fingers, tinned spaghetti hoops and Wall’s sausages. He is used to drinking a lot of fizzy drinks but these make him hyperactive. He has been having milk, juice and water with me.’ Very sensible, I thought, because research has shown that diet can play quite a large part in children’s behaviour, particularly if they are sensitive to additives, which many children with behavioural problems are.

‘Thanks,’ I said to Veronica, refolding the paper.

‘And I should keep him off the E numbers,’ she said with a smile.

‘Absolutely,’ I agreed.

After Veronica had left I took the bags and boxes up to Reece’s room. I told him I would start unpacking his clothes and he could help me if he liked, or he could continue watching his programme. He didn’t answer or turn in my direction, but remained absorbed in the colourful cartoon, which was designed for children aged about four. I opened the suitcase and began taking out his clothes, folding and hanging them as I put them into the wardrobe and drawers. As I worked I repeatedly glanced in Reece’s direction. He remained relaxed but oblivious to my presence. His eyes followed the rapidly moving cartoon figures, which were now on an adventure in a park. Occasionally he made little noises, sometimes grunting his approval at something that was happening on screen and repeating the odd word as the story unfolded. It crossed my mind that Reece seemed to relate far better to the television than he did to people, probably as a result of all the years he’d spent in front of the television that Karen had mentioned. And I thought that while television might be a useful tool in managing Reece’s behaviour his viewing was going to have to be very carefully regulated. I wanted him to engage and interact with people, not a screen.

When Lucy and Paula arrived home just before 4.00 they did not, as they had expected, enter a house heaving under the strain of an out-of-control child, but one that was quiet, with a child sitting serenely on a beanbag, watching television, while I unpacked.

‘Up here,’ I called as I heard the front door go.

Leaving their bags and coats in the hall they came straight up. They knocked on the bedroom door, which we always do before entering a bedroom other than our own, and came in.

‘Hi,’ I said. ‘This is Reece. Reece, these are my daughters, Paula and Lucy.’

The girls said ‘Hi’ and ‘Hello’. Reece grunted what could have been an acknowledgement while not taking his eyes from the screen.

‘I’ll finish unpacking this case,’ I said to them. ‘Then I’ll think about dinner. Have you had a good day?’

‘Yes,’ Paula said.

‘Not bad,’ Lucy added.

The girls looked from Reece to me and back again. I knew what they were thinking: that the child who was sitting so contentedly and now smiling at The Basil Brush Show couldn’t possibly be the one I’d told them to expect. However, I also knew, given what I’d previously seen of Reece’s behaviour, that things could revert very quickly.