Читать книгу Behind Palace Walls - Cay Garcia - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The arrival

ОглавлениеKING KHALID Airport feels like another planet. I am the only woman who isn’t shrouded from head to toe in black. The aircon is set so high that even in my winter clothes, I am freezing.

It’s not the majestic international airport I’d expected. What I see now falls terribly flat. The arrivals hall has a depressing look and a sombre mood hangs over the place.

I’m not too alarmed about looking so out of place as I have been assured that the princess’s secretary will have an abaya for me at arrivals.

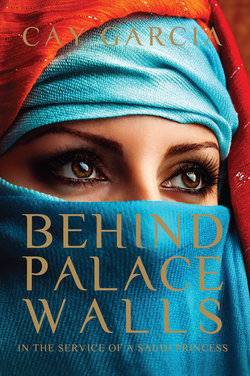

In Islamic countries, all parts of a woman’s body that are awrah – not meant to be exposed – are covered by an abaya, an outer garment, and a hijab, a head scarf. In many of these countries, a woman’s face is not considered awrah. But in Saudi Arabia, awrah includes every part of the body, besides hands and eyes, so most women are expected to wear a niqab, a veil over the face, as well.

There are several queues. The signage is in Arabic so I follow the people ahead of me. A man in a scary looking uniform strides up to me. His arrogant bearing makes me feel alarmed. Without making eye contact, he pulls my passport out of my hand. He says something in an urgent tone, still avoiding eye contact, and points to another queue. I’m relieved – it turns out he is just trying to help me, or perhaps he it’s the black leather boots!

At the last checkpoint, the official behind the counter looks at my passport, then at me, then back at my passport and says softly, “This is not a good photo.” I have to agree, and I laugh with him. It was taken straight after graduation, when I was in the grip of severe flu, my eyes barely open – and the new rule of having to pull your hair back off the forehead doesn’t help one bit. He is not a local. No Saudi man would make such a flippant comment.

After my photo and finger prints are taken, I make my way to the public arrivals hall. Among the throng of men waiting to pick up passengers, I expect to see the princess’s secretary holding a board with my name on it. I scan the hall. After 30 minutes of hanging around, the crowd thins. Still no sign of the secretary.

That was my first lesson in Saudi time-keeping. If you are punctual, get over it; waiting is just part of Saudi life.

After an hour of wandering around, looking for someone to claim me, I give up. I find a seat in the back row of a cluster of seats and take out my book.

I discreetly watch the comings and goings around me. I am fascinated. The crowds have thinned but the hostile stares haven’t. Another hour passes.

Then I notice two men walking briskly in my direction. They stop right in front of me, towering over me, smelling strongly of cologne. “Passport!” says the taller one. I hand it over. They inspect it briefly then start walking away, summoning me to follow. Half relieved, half apprehensive, I scramble to get my luggage together and follow. That is the last I saw of my passport.

We walk into an underground parking area. I’m lagging behind, struggling with my luggage, still in Western clothes – no help is forthcoming and no abaya either. I am elegantly dressed in a long black and grey tailored skirt, a white shirt that lost some of its crispness somewhere over Africa, a red, black and grey paisley scarf and a black tailored jacket and black boots – only my hands and face bare. Yet the hostile stares continue. As my luggage is stowed in the boot, none too gently, and I’m ushered into the back seat, still not a word is uttered. The tint on the back windows is so dark that I can barely see out.

We leave the airport building and join the nightmarishly congested traffic. I’d read that 19 people die as a result of car accidents here every day. The reason Saudi has one of the highest accident rates in the world is immediately apparent – cars weave in and out of lanes at breakneck speed, passing with only a thumb’s-width between side mirrors. Most drivers keep one hand on the hooter, the noise is grinding.

Reckless driving is part of the national identity. Wealthier men drag race high-end cars and the lower-classes “drift” their cars through traffic. These youngsters weave in and out between other cars while they intentionally over-steer, sometimes missing other drivers by a very small margin.

Saudi women are not allowed to drive – even though thousands own motor vehicles. The thinking is that they’d increase car accidents, they’d overcrowd the streets, they’d leave the house more often, their faces would be uncovered, and they’d interact with males, which would contribute to the erosion of traditional values. A leading Saudi cleric has even argued that women run the risk of damaging their ovaries and pelvises if they drive.

But not all Saudi women accept the ban on driving. A couple of years ago, a handful drove through Riyadh in protest. They were arrested and released only after their male guardians signed statements that they would not drive again.

The women were suspended from their jobs, their passports were confiscated and they were forbidden from speaking to the press. About a year after the protest, they were permitted to return to work and their passports were returned. But they were kept under surveillance and passed over for promotions.

More recently, a few women used social media to publicise their cause. They got behind the wheel, filmed themselves, and uploaded the videos to YouTube.

Despite the alarming drive and dark windows, I manage to take in some of the surroundings.

The buildings thin and we seem to be heading straight into the desert. Doubt flares, my thoughts run wild. I’d expected the secretary to be a woman, accompanied by a male driver. Am I hanging with the right crowd? They speak in hushed tones, the older man in the passenger seat turning often to stare at me. I feel as if I’m being assessed for something.

We reach what appears to be the edge of the city. I have my face plastered to the opaque window – I’m straining to see out, but it’s also an attempt to avoid the old man’s scrutiny. I am surprised at the ultra-modern buildings. The traffic does not let up.

At each green light, drivers further back honk at the cars up front to hurry – each turning lane has only 40 seconds to make it through. Above each set of lights, a large digital screen counts down the seconds till the lights change. Red is allotted 160 seconds. I would often see one of our drivers nod off during the wait. They work long hours.