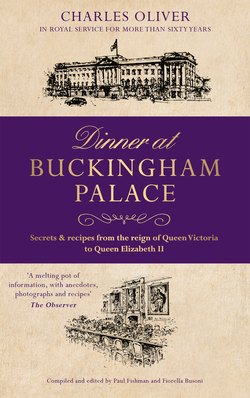

Читать книгу Dinner at Buckingham Palace - Secrets & recipes from the reign of Queen Victoria to Queen Elizabeth II - Charles Oliver - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Entremets

ОглавлениеLes Truffes au vin de Champagne

Les Artichauts à la Lyonnaise

Le Buisson de Prawns sur Socle

Les Anguilles en volute au Beurre de Montpellier

Les Tartelettes de Framboises

La Gelée de Groseilles garnie de Pêches

Les Génoises aux fruits transparents

Les Petits Pois à la Française

Les Haricots Verts à la Poulette

L’Aspic de Blancs de Volaille à la Bellevue

La Salade de Légumes à l’Italienne

La Macédoine de Fruits

Le Bavarois de Chocolat Panache

La Crème aux Amandes pralinées

Les Petits Pains à la Parisienne

Les Gâteaux de Pithiviers

In the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign, as during the reigns of previous monarchs, state dinners were expected to be ostentatious banquets of many elaborate courses with a vast choice of extravagant dishes, many not to modern tastes. This dinner was one of those. Charles Francatelli, chief cook to Queen Victoria from 1840 to the end of 1841, spared no effort, or living creature, in order to produce such sumptuous feasts. He always made sure, too, that there was a generous supply of sweet dishes to satisfy the Queen’s sweet tooth.

This was for the privileged minority, of course. Middle-class families ate simple meals, though not quite as simple as those of today’s middle-income families, while the poor consumed small quantities of cheap foods, such as fish and chips, sausage rolls, bread and jam – and very often they didn’t eat at all. There was widespread hunger in Victorian times, and thievery and prostitution were rampant, largely due to the lack of food. It was small wonder that the impoverished would congregate in the street outside the royal kitchens, and each day many went away satisfied with a liberal helping of leftovers from the royal table.

Victorian high society frowned upon women – ladies – displaying enjoyment of eating, considering it unbecoming. Queen Victoria herself in later life showed herself to be a frugal eater, at least at breakfast, when she reportedly ate only a single boiled egg, served in a gold-plated eggcup with a gold spoon. Evidence from portraits, photographs and various contemporary accounts suggest otherwise, though. As a girl and young woman, she was warned that she was likely to become fat, and her weight fluctuated a great deal. ‘If I was to give you an opinion,’ remarked her Uncle Leopold, ‘I should say that a certain little Princess eats… frequently a little too much, and almost always a little too fast.’ Decades later, she was still getting through meals quickly, which was a pain to her guests as protocol meant they had to stop eating when she had finished. In later years, especially after the death of her beloved Prince Albert, it is clear that she consumed a great deal more than a single boiled egg. As the head of an empire she had to set an imperial table; as empress, she could have what she wanted. A book, published anonymously in New York in 1897, The Private Life of The Queen by a Member of the Royal Household, while protesting rather a lot that she ate little, commented on her fondness for sweet things: her particular favourites were ‘chocolate sponges, plain sponges, wafers of two or three different shapes, langues de chat, biscuits and drop cakes of all kinds, tablets, petit-fours, princess and rice cakes, pralines, almond sweets, and a large variety of mixed sweets’; in addition, ‘Her Majesty confesses to a great weakness for potatoes, which are cooked for her in every conceivable way.’

In later years, one course Queen Victoria insisted should be available for lunch was a dish of curry and rice, served with considerable ceremony by two Indian servants resplendent in uniforms of blue and gold. Victoria took pride in being Empress of India and loved to surround herself with vividly attired Indian footmen and waiters. It could reasonably be supposed that it was as much the ceremony of the serving as it was the tastiness of the dish itself that prompted her to order it daily.

During the closing years of her reign, Victoria had a residential staff of more than a hundred people at Windsor and a kitchen staff of forty-five, presided over by the head chef, Monsieur Juste Alphonse Menager. For state celebrations, extra members of staff were employed – for the Diamond Jubilee in 1897, twenty-four additional chefs were brought in to prepare the food, which took several days.