Читать книгу Make Your Own Walking Sticks - Charles Self - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION: A FEW GOOD STICKS

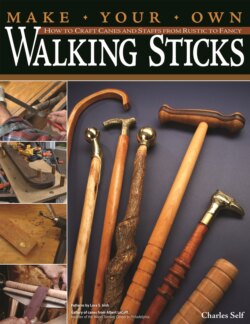

These interesting canes are among the projects you will find in this book. You can make most of them with basic shop tools.

Walking sticks, canes, and staffs have been valuable items for a great many centuries, probably ever since someone crawled out of a cave, discovered his leg hurt, and found a branch to add support on that side. Those early walking staffs served much the same purposes they serve today: being useful for those with a sore leg, foot, or hip; handy for drawing maps on the ground; and helpful for pointing out directions.

Once upon a time, gentlemen carried canes as a status symbol, though that use died out many years ago. My own first memory of walking canes is of a shiny black cane given to me by a dapper uncle, about the time that uncle retired from dapperness.

My next memory of small sticks, outside of batons in the hands of orchestra conductors, is from the military. At Parris Island, South Carolina, the Marine Corps drill instructors carried swagger sticks, at least while I was there. They were used more for intimidation than anything else—I don’t know of anyone in my generation (or later generations) of Marines who got more than a light tap with the swagger stick. That light tap was more than enough to command attention.

THE POLITICS OF CANES

Over the millennia, walking sticks became important as indicators of power (scepters) and of justice. By the early seventeenth century, because of the use of cane (malacca) as a material for certain types of walking sticks, walking sticks in general began to be known as “canes.” For 300 years, the cane was an accessory that denoted wealth when made of expensive or hard-to-work materials. U.S. history shows that Ben Franklin used a gold-headed cane. President Andrew Jackson was the owner of a sword cane, but, given modern times, that’s not an item we’ll present as a project here.

Use as an offensive weapon, even without a sword, was not unusual. Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina nearly killed Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in 1856 by beating him with a cane after Sumner insulted a kinsman of Brooks. Back in 1798, Roger Griswold, a Federalist representative, walked across the chamber to Matthew Lyon and pounded on that Republican’s head and shoulders with a hickory cane. A few days earlier, Lyon had spit in Griswold’s face when Griswold called him a coward, so few were surprised by the caning. Though walking sticks and canes are neither as prevalent nor as in fashion as they once were, they still have a place in modern times.

HANDMADE OR STORE BOUGHT

Walking staffs, or hiking staffs, have gained popularity in recent years as more and more people take to the trails for exercise and fun. They have become much less a statement and much more a utility device for those of us who need a bit of assistance in hobbling along. I doubt my interest in the subject would have reached the stage of construction if I hadn’t damaged my knees as a youngster, but, with that damage, I had to take a long look at what the medical suppliers were offering. Adjustable metal canes that feel flimsy and look cheesy just don’t do the job.

Store-bought walking staffs are interesting, but they still lack any real variety, mostly being made of aluminum with rubber grips and only the maker’s brand for decoration. For woodworkers, that is just not good enough. Making your own walking stick means you’ll have the perfect fit and something that makes a statement about who you are. A handmade staff will stand up to rigorous use over time as you use it to balance as you cross a stream on rocks or a log, to judge the depth of the stream if you have to ford it, to check the other side of a large log or rock so you don’t step into a nest of snakes, or just to aid you in getting around town.

STICK, CANE, OR STAFF

Let’s also take a moment here to talk about what defines a walking stick, a cane, and a staff. Canes tend to have arched tops and to be a bit lower than belt height, possibly 31" to 36". Walking sticks are fairly slender, lack a curved top, and are about the same length as a cane. Walking staffs are breast height or taller in most uses, though they can vary from as short as 40" on up past 54". None of these sizes are set in stone, however, nor are they published as law.

STICK, CANE, AND STAFF FEATURES

Until recently, walking sticks, canes, and staffs have mostly been made out of wood, often mahogany with some ebony, hickory, oak, maple, and other species, too. Today, commercially available ones tend to be made of metal, usually aluminum tubing painted or anodized, and adjustable for height.

As I mentioned earlier, cane handles use a rounded hook, which makes a good handgrip. It is probably related to the old shepherd’s crook, with its long shaft and the ending hook that allowed the shepherd to pull a single lamb from the flock. There are also flatter cane handles, as you’ll see with a couple of the brass versions, though they do have a slight arc to them.

These curved canes can be made by slicing the wood into thin layers and gluing it together around a form, as you will see later in this book, or by steaming the wood until it softens enough to bend. Steaming is an interesting process, but it is beyond the scope of this book, so we won’t cover it here. You can find a little more information in “A Note on Steam Bending” on here.

Decorative knobs and handles abound for sticks, canes, and staffs. The most complexly decorated provide a standard cane handle on a tapered cane body, but there are also old hame balls (harness gear for horses) that mount nicely on cane or walking staff bodies.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Within the first section of this book, you’ll find everything you’ll need to know about getting started making canes: a description of suitable woods and what they’re like to work; an introduction to some useful hardware bits and pieces, including handles, joins, and such; a look at some useful tools, both hand and power, for making canes; and some information on finishing. There’s also an inspirational gallery from Albert LeCoff, founder of the Wood Turning Center in Philadelphia.

After that, it’s on to the projects in the second section of the book. I’ve included 15 to get you started, ordered from easiest to most complex. The first projects are super-simple variations on a single design, and they’re easy to complete, so, even if you’ve never made a walking stick, cane, or staff before, you should feel at ease making these projects. The first projects also showcase some great ways to modify the designs included here—altering the type of wood suggested, adding a different handle, or using different types of finish. Those looking to further embellish their walking sticks, canes, and staffs will find over 25 original carving patterns from renowned artist Lora S. Irish. Once you’ve worked through your favorites, you’ll be well on your way to making your own designs for a variety of projects.

[bad img format]

Here’s the whole collection, with the footed cane made by Del Stubbs of Leonard, Minnesota, standing at the left. Ironically, given LeCoff’s injury, while turning the shaft of this cane, Stubbs’ skew chisel suddenly clicked on metal: He’d discovered a bullet lodged inside the wood.

Albert LeCoff Tribute Cane Collection, 1989

Artists: Roger Barnes, Ed Bosley, Rod Cronkite, Frank E. Cummings, III, Walter Dexter, Leo Doyle, Dennis Elliott, David Ellsworth, Giles Gilson, Michelle Holzapfel, Todd Hoyer, C.R. “Skip” Johnson, John Jordan, Bonnie Klein, Frank Knox, “R.W.” Bob Krauss, Andreas Kutsche, Dan Kvitka, Stephen Loar, Johannes Michelsen, Bruce Mitchell, Michael Mode, Stephen Paulsen, Michael Peterson, Richard Raffan, Bob Sonday, Ric Stang, Bob Stocksdale, Del Stubbs, Christopher Weiland

H 68" x Diam 24"

Various materials

From the Albert and Tina LeCoff Collection

Photography by John Carlano