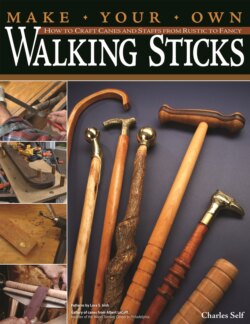

Читать книгу Make Your Own Walking Sticks - Charles Self - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWOODS FOR WALKING STICKS, CANES, AND STAFFS

Selecting the right wood for your walking stick, cane, or staff really comes down to a wood’s durability, its availability, and your personal preference. Generally, sticks, canes, and staffs are made of hardwoods for good reason. Hardwood is stronger in almost all ways than most softwood, so it breaks less easily and wears less quickly. Hickory, for example, makes a wonderful cane or walking staff wood, as do maple, locust, and sassafras (which has a wonderful aroma as you’re working it). However, almost any wood that turns or scrapes easily is worth considering, even if I don’t mention it in this section.

WOOD SPECIES

The list of appropriate woods for walking sticks includes fine hardwoods, such as cherry and walnut, and many of the exotics. More modern examples include mesquite, sassafras, jarrah, and African mahogany (see Figure 1.1). The chart on here to here includes photographs of woods to aid you in deciding on appearance. The list is far from complete, but it does cover most of the woods of interest to cane makers in this hemisphere. African and Asian woods are available but are not covered here simply because what you see listed is what is most likely to be easily found these days.

Figure 1.1. Mesquite, here being chamfered with a small plane, is one of the many fine woods you can use for canes. It is hard, lustrous, and takes a beautiful finish.

A NOTE ON COMBINING WOODS

Woods to be joined must match well: Too much difference in moisture content between two woods creates problems, as do great differences in wood structure. For example, teak, with high silicon and oil contents, does not bond well with any other wood. It is even difficult to bond it to itself, usually requiring an epoxy.

When the same species of wood is used, you get the best gluing results and the longest and strongest hold. For example, attaching pine to pine or walnut to walnut works best. If part is walnut and part is pine, difficulties may arise. However, with small cross sections, as used in most sticks, canes, and staffs, these difficulties aren’t going to be overwhelming, provided all the wood is dried to about the same moisture content. None of our projects has extensive wood movement problems because even the larger sticks, canes, and staffs are small as wood projects go.

PLANING FOR CHEAPER WOOD

Saving money by buying rough wood (boards that have not been planed to final size and surface) requires two things: first, patience; second, access to a planer. You’ll also need outdoor space where the wood can be stacked with its top covered, so this is not a solution for the city-dwelling woodworker. It is also not a real solution for someone who doesn’t have ready access to small sawmills that will sell rough-cut wood. A moisture meter is handy: The model I am currently using has a bottom measure of six percent on a diode light. Six percent is the level recommended for furniture making, but anything under 12% works fine with canes and similar projects.

Planing may take place when moisture levels drop to about 15%. Some hardwoods are difficult to plane on lightweight home shop planers, and wetness doesn’t help at all.

Lightweight planers do a fine job of planing many woods, from pine to walnut. They must work harder with white oak, but will do the job if you let them cool down after every 30 minutes of use. These are not production machines. If you treat them like production tools, they’ll wear out very quickly.

Cane and stick makers require relatively small amounts of lumber, unless you decide to produce major numbers of gifts or items to sell, so the above advice may not apply to you, but you will be starting a number of projects with wood that is over 1½ inches thick, so seasoning your own wood and smoothing it is a possible money saver.

PURCHASING WOOD

If you’re buying these woods from a lumber mill, ask for reasonably straight pieces that are free of checks, cracks, and knots. Finished sizes commonly needed are about 2½" wide by ¾" thick. Reasonably straight and strong woods make the best canes, with the exception of willow or other branches that are twisted from growing with vines curled around them. Properly seasoned wood is easiest to handle, too, and is usually best because you can expect fewer changes (like checks and cracks) from the time it leaves your hands until the time someone uses it.

USING FOUND WOOD

Most wood is readily available at lumber mills or online, but some wood you can gather while walking in the woods (see Figure 1.2). Willow shoots come to mind as good finds on a woodsy walk, but if you’re not on your own property, it is a very good idea to ask permission before cropping someone else’s willow wands, or even sumac and similar bushes. Locating found wood is generally serendipitous—you can sometimes find it in your own backyard, near new contruction sites, and in any number of other places. With a little bit of experience, you’ll soon develop an instinct for good sources in your area.

Any of the woods listed in the chart on here to here will work well as found wood or as prepared lumber. Most woods are easy to carve when they’re green, but seasoning found wood produces the best and most consistent results. Season found wood slowly to reduce splitting and checking, especially if you’ve carved patterns in the wood (see the Storing Wood section on here for more information).

Figure 1.2. These pieces of found wood will create fantastic walking sticks and canes.

HARVESTING ROOTS

Roots, which are really just wood that grows below the ground, make interesting canes. If the roots are not large enough for entire sticks, canes, or staffs, they often have shapes that make fantastic handles. Keep an eye open at the base of dead or dying trees, or even at the base of stumps. You may need to clean this wood more thoroughly because it is mostly covered in dirt, but you can otherwise treat it just as you would any other found wood.

If you do much root cutting, a handsaw is quickly ruined. I like a cordless reciprocating saw. Use that with pruning blades either 9" or 12" long and change blades when they’re dull. It is heavier than a handsaw, but not too cumbersome to carry.

A STICK MAKER‘S GUIDE TO HARDWOODS

STORING WOOD

Despite your best plans, you may not be able to make your cane or staff as soon as you buy or find the wood. If you store the wood properly, it will be available for you when you’re ready and not have lost any of its quality.

To properly store prepared wood, simply stack it horizontally with supports every 12" until the moisture content is at an appropriate level (under 12 percent) (see Figure 1.3). A moisture meter is handy for this process, giving you the exact moisture percentage for the wood. Otherwise, dry any wood about a year for each inch of thickness.

Figure 1.3. Properly stored prepared wood is stacked horizontally with supports and stickers to achieve a 12 percent or lower moisture percentage. Though this is, of course, more wood than most woodworkers have on hand, it is still an excellent example of how to properly store wood.

To properly store found wood, like willow wands or vine-twisted sassafras, first remove any dirt, dust, or other debris using a rag and water. You can also use a drawknife to clean the bark off, if desired. Then, stack it horizontally with supports every 12" and wait until it reaches the appropriate moisture content, just as you would with prepared wood.

BENDING WOOD

Most North American woods, hard or soft, bend decently, but not all do. Many fruitwoods, like apple, might bend well if found in longer lengths without many knots, but, because most fruitwood branches come from orchards, finding bendable lengths of 40" is not easy. Red cedar is also a problem because it often has lots of knots that tend to snap when the wood is bent. Red and white oak, ash, sweet gum, alder, hickory, maple, black locust, tulip poplar, magnolia, and similar woods all bend well in thin strips, as do walnut and cherry, our premier furniture woods. Some exotics don’t bend well at all, even in thin strips.

A NOTE ON STEAM BENDING

In this book, I’ve chosen to use lamination, rather than steam bending, for the sticks and canes with curved handles because lamination is easier and requires less gear. However, steam bending is a reasonably simple process and thus a practical alternative to lamination. Both processes allow you to create rounded edges and other effects for your finished projects.

If you decide to try steam bending, realize that you must find a source of steam and create a place to catch the steam. (Be sure that you do not use PVC plumbing pipe in this process, because it bends when it gets hot and makes a mess.) Lee Valley offers a group of products, including an instruction manual, that can be a big help in steam-bending work.

SIZING WALKING STICKS AND CANES

Before you select the wood for your project, it’s important to know what you want the finished size to be. When you make your own cane or stick, you can readily, and easily, adjust it for height. A walking stick might be as little as 42 inches long or on up past 54 inches, if desired. To size a single-purpose walking stick, hold out your hand at a comfortable angle, imagine you have a stick in your hand and are walking on rough ground. Measure, or get someone to measure, from that hand to the ground, and you’ll have a near perfect fit (see Figure 1.4). Try it with a branch or a narrow ripping to be sure.

With a knob handle, the walking stick may become a cane, providing walking support even on smooth surfaces for those with leg problems. Canes are shorter than walking sticks and should be measured so that the arm is slightly bent at the elbow and the wrist, with the hand falling naturally. Drop a tape to the ground from the curled palm of the hand. Confirm the measurement by experimenting with a cane blank sawn out of pine. Make it longer than you think it ought to be, and then shorten it an inch at a time.

Total cane length depends on user height. For general use, 34 inches works for moderately tall people, while 30 inches works for fairly short people. As with all canes, measurements are approximate and need to be fitted to the wood on hand, the fittings on hand, and the user’s needs as far as size and appearance go. Measurement of overall height must always allow for a couple of inches of rise for the handle, about half an inch rise for the brass joint, if any, and almost no rise for a rubber tip. Be sure to figure in this extra rise.

Figure 1.4. To figure out the proper length of your walking stick or cane, imagine you have the stick in your hand and are walking with it; then, drop a measuring tape to the ground from your hand.

Size handles to fit a particular hand, unless you’re using a naturally shaped limb or root; then, nature determines the sizing. Even with a natural handle, it’s best to use smaller crooks or roots for people with smaller hands. Handle size is not an imperative for most people, but it does add to comfort. Take a rough measurement of the lightly closed hand across the palm side to get the thumb knuckle in. If the result is 4", add an inch or an inch and a half and use that for a handle length. Handles about an inch in diameter seem to be nearly universal, though some are slightly thinner or thicker.