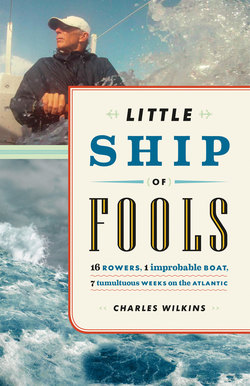

Читать книгу Little Ship of Fools - Charles Wilkins L. - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеAS THE WINTER DEEPENED, Roy’s communication with the crew became increasingly fitful. There were stretches when we didn’t hear from him for weeks. He had taken time away to build another rowing boat, a smaller craft, for a team of British rowers—three of whom, ironically, had in recent months departed our own dwindling crew.

Roy’s own abrupt departure from the expedition in the late spring of 2010 might have been predicted. By that time, he had apparently fallen out with David, and the project was sinking into debt. The boat was far from ready for the ocean. No one knew quite what to do or think about Roy’s going. On the downside, we had lost our captain, a mercurial mastermind who had brought multi-hulled boats to ocean rowing and in so doing had revolutionized the sport. What we had gained, meanwhile, was the freedom to reshape the adventure, free of the singular fixations of an increasingly unpredictable leader.

Until now, the greatest mystery for the crew had been the nature of David and Roy’s connection, and of David’s connection to the boat. In the early days, David had been pitched to the crew as an engineer who would be aboard but not rowing, presumably as Roy’s assistant. Steve believed David was the money man, and that Shelter Island Boats was Roy’s operation. But with Roy’s departure, it quickly became clear that David, a man with the subtlest of egos, owned not just the boatyard but the boat and that he knew a good deal more than we had imagined about boatbuilding. Indeed, with a gaggle of his Long Island pals, two of whom were fellow Georgians, he was prepared now to take over the project. His motivation compared to Roy’s (whose was creative and competitive, as well as financial) was largely a matter of integrity. He and Roy had accepted money from those who had signed on, and David was not about to stiff them if he could help it.

Almost immediately, Steve, who with Roy’s departure was back in the fold, broadened his influence on the voyage. My own hope was that he would assume the captaincy, which would have been his for the taking. But he didn’t want it. He was an experienced Great Lakes sailor but did not feel confident in his navigational skills on the Atlantic. I think he believed too that the captain of an ocean rowboat should have made the crossing at least once as a crewman. However, he did set about bringing new people to the expedition, as did Nigel—an effort that would eventually put seven Canadians, a modest plurality, aboard an essentially American boat.

For the moment there were twelve of us. David wanted sixteen. Steve’s foremost acquisition, as it turned out, was not a Canadian but a Californian whose route to Big Blue was more circuitous, unlikely, and coincidence-ridden than the plotting of a Victorian novel. It began perhaps three months after Roy’s resignation, when a Thunder Bay skier and endurance cyclist named Frank Pollari, a friend of mine who is legally blind, had an inkling he might like to join our little band. He began to train. However, before he committed to the voyage he wanted to test himself on the ocean, in particular to see if an old vulnerability to seasickness still existed. Through Google, he located a veteran female rower in Long Beach, went out to see her, went rowing, and spent much of his time aboard with his head over the rail, puking into the Cali-fornia surf. And came home. And more or less forgot about ocean rowing.

Until a day in late September, when he received an email from Steve, who knew of Frank through me and wanted to know more about this mysterious, good-natured woman who had taken Frank rowing on the Pacific. Steve could not help but notice on her blog that she had rowed both the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, and had returned recently from a triumphal row around Great Britain.

The question was: Would she row for us? Might she accept the vacant captaincy? There is in the sport a prestige in being at the helm, where she had not been on any previous row. Plus, it was assumed that the boat’s experimental design and the desire for a world record would interest her. Steve petitioned her in an email—and received an answer the next day. And sent word to the rest of us that she was at least open to the idea.

We held our breath as she flew cross-country to New York to meet David and to check out the boat. And celebrated quietly as news came down, beneath the radar, that she had liked what she’d seen.

So it was a week or so later that the soft-spoken grandma from Xenia, Ohio, via Long Beach, was introduced to the crew, via email, as our new commander, Cap’n Angela—excited, as she put it, to be part of “this historic ocean row.”

MEANWHILE, in Thunder Bay, not everyone was as magnanimous about my decision to row the Atlantic as I might have liked. “Are you doing this because you want to die?” I was asked at one point by a smart-aleck acquaintance—to which I responded, in finest mock Confucianism, that I was doing it “because I didn’t want to die.”

“But what is the meaning of it?” I was asked by a nettlesome neighbor.

“Discovery,” I thought to tell her, adding that I assumed I would be better able to report on such abstractions when I returned.

“And if you don’t return?” she said slyly.

For now, I told her, I had discovered meaning in my training, which, happily, in mid-June, moved outdoors onto water—at Clear Lake, in the Muskoka region of central Ontario, where the family keeps a summer cottage. What a relief it was to be splashing, to be moving, to see shoreline passing, after ten months indoors on the old black C2 torture machine. My outdoor rowboat, it needs be said, was not one of those spiffy needle-nosed skiffs that you see rowers using in the Olympics but an old Norwegian sailing vessel—a Gresvig 5—given to me by my parents on my twelfth birthday. With a tuck here, a tap there, I converted it into a rowboat that worked the muscles of the upper body and abdomen to the point where several times that summer I was approached by people speculating on how youthfully and seductively “ripped” I must be somewhere beneath my T-shirt. And of course I was. Profoundly. However, as you might imagine with a guy of my age and inclinations, mine was more a metaphysical ripping, an inner muscularity, than one merely of the flesh.¹

And the ripping did not stop at my pecs, nor in the well-lit recesses of the chi. A further feature of this dutiful if moldering craft was that its old centerboard slot, which transected the seat directly beneath my hard-working glutes, regularly ripped holes right through my pants and on into what was left of the underlying muscle. To someone of lesser ambition this might have presented as a drawback. However, because of it I was infinitely better prepared for the salt and “rub” sores that accrue to all transatlantic rowers.

In contrast to the skepticism of my detractors, I enjoyed the acknowledgment and encouragement of, among others, bank executives, artists, politicians, lawyers, professors. Some said they’d love to be going with me. There were times when I wished they were going with me. Or going instead of me. For despite my anticipation and training, I harbored little in the way of certainty about the upcoming months. Which was preferable, I believed, to being too certain. Ricky Wallenda once told me that a wire walker is more likely to fall if he succeeds in overcoming his fears. So he nurses those fears as he weathers the improbability of his choices.

Likewise, I nourished my own modest fears and uncertainties, in the hope not just of weathering but of welcoming the consequences of this thing I had chosen to do. And therein I located both the thematic and narrative arcs of the next few months of my life—arcs animated increasingly by my improbable makeover as a high-stakes rower, an extreme athlete, or, more pertinently, an extreme convert to the uncertain art of keeping the adventure alive.

WHILE THE CREW trained, David and his Shelter Island kinsmen were at work on the boat—strengthening it, rebuilding parts of it, generally gussying it up and fitting it for the ravages of the sea. David believed that Roy, whose idea was to keep the boat’s weight down at any cost, had somewhat under-engineered the vessel, perhaps leaving it vulnerable to the tough going ahead. Roy’s earliest plan had not even included a cabin; crew members were to have slept in compartments in the hulls or on an open platform between them. In defense of Roy’s standards, it should be said that in 2006 he had built an ocean rowboat named Orca, a gorgeous tri-hull (two of the hulls were in effect sealed hollow outriggers) in which he and three others raced across the Atlantic against a boat named La Mondiale, piloted by the famed Scottish ocean rower Leven Brown. Coincidentally, it was La Mondiale’s crossing time of thirty-three days (Orca crossed in thirty-four) that established the world record we were about to go chasing.

But Big Blue was more vulnerable than Orca. As a catamaran, she would be subject to enormous structural pressures in that her hulls would be torqued hard and constantly in opposite directions by the waves. The cabin would be pounded from below. Her advantage was that her twin hulls would allow eight rowers to work at once, more than had ever rowed together on an Atlantic crossing.

From afar, Roy protested the contamination of his design, while David made it clear that it was his boat now and that the safety of the crew would not be compromised beyond the fateful compromises that were already intrinsic to such a voyage.

Impressed by Big Blue’s design—by “David’s vision,” as she put it—Angela nonetheless initiated two small changes: the addition of a toilet and of a small gas burner for heating water. Where there was a grandma on the raging main, there would also be a cup of tea.

SIX WEEKS LATER, in mid-November, fourteen of us flew or drove to New York City and rode in crowded vehicles out the Long Island Expressway, past Amityville and Fire Island and the Hamptons. Eventually, at Greenport, we caught the night ferry to Shelter Island, where, during a three-day trial, our experience of the Atlantic began.

At this point, I had not actually seen the already storied rowboat that had occupied my thoughts and dreams day after day for so many months. And I had developed a deep hankering to do so. And was not disappointed. As we spilled out of the van that had transported us from JFK, the boat sat dramatically before us in the lights of the boatyard, spidery and futuristic in its new coat of paint. For half an hour or more, we circled it in a kind of trance, patting and rubbing at it, tummying up to it, peering into its recesses, fiddling with its hatches and seats, unable to get the smiles off our faces. The $10,000 I had put in, which at the time had struck me as a chunk, seemed suddenly small, while the boat, or at least its aura, expanded like Topsy in our midst.

Structurally, Big Blue is a study in simplicity: two narrow hulls, each nearly forty feet long, joined by aluminum beams so they sit twenty feet apart. Each hull has four rowing positions, while the joining beams support a tidy little spaceship of a cabin.

“It looks big, but it’ll be very small on the ocean,” growled a low voice behind me. I turned and a man a few years older than myself was looking at me with drooping but animated eyes. He said, “You must be Charlie; I’m Tom Butscher.” He was one of Steve’s would-be recruits, as yet undecided, who had traveled by train from his home on Toronto Island in order to mingle with the crew, take a trial row, and make up his mind. (The following morning he said to me quietly, “Ya know, I don’t think I’ll bother making up my mind—too much pressure. I’ll just go.” And he committed to the journey then and there.)

In all, meeting the crew was like encountering the characters out of a novel I’d been reading for weeks: Ernst from Vienna; Sunshine Liz from the north side of the island; Aleksa the firefighter from Deer Park; Rowboat Ryan from Chattanooga; Louise from bluegrass country; Sylvain from Gatineau; Paul from Shelter Island.

Paul was not a rower but had our respect and attention because he had worked on the boat, as had the pair of Georgian expats, relentless smokers, who shook hands dutifully and went back to building the rudders.

And of course David—David—that most honorable of guys, who had picked up the pieces in Roy’s absence and had made a boat that with any luck would bear us all off to sea.

Of the lot, it was Angela who seemed most like a character who had somehow found her way into the wrong novel. More subdued, sweeter tempered, driftier than any of us had imagined, she was, at six-foot-two, an impressive assemblage of tree trunks and upholstery and scar tissue. Thirty years ago, as she had explained to us on the way up from JFK, several of her vertebrae had been smashed while she was playing basketball for the U.S. Marines. It was her first game; she was to have been a star. A dozen years later, the military’s best orthopedic surgeons had botched the operation that was intended to fix her up. “No hope, no recourse,” she shrugged—adding that, these days, with the exception of short hauls, where her leg braces were all the support she needed, she traveled in a wheelchair. “Or on a surfboard,” she brightened. Or on her beloved rowboat back home in Long Beach.

On the morning after our arrival, David hitched his wide burgundy half-ton to Big Blue’s trailer, and, following a police escort, pulled her ceremoniously from the boatyard. In our scarves and squall jackets, we fell in behind, pilgrims to Canterbury, chattering and laughing as we walked a mile or more of treed residential roadway to the launching ramp.

There, over a period of several hours, in the cold November afternoon, we attached the rudders and rowing riggers, ate lunch, kibitzed and fussed until, finally, at perhaps 5 p.m. we slid the boat ever so gently off its trailer into the shallows of the Atlantic Ocean. And watched in fascination as it floated free, seeming barely to create a ripple.

Off we rowed into a grayish and misty twilight—up the east side of Shelter Island, not far from East Hampton and Montauk, where my only previous look at the local waters had come from the Steven Spielberg movie Jaws.

For sixteen hours straight we worked exactly as we would at sea: two watches of rowers in two-hour shifts, alternating port and starboard hulls, in order to balance the strain on the shoulders, neck, and torso. During the year or more I had been involved in the expedition, I had been asked perhaps a dozen times: Why two hours—why not three, to allow a decent sleep? And the simple answer is that three hours (great for sleep) is too long a period for rowing. At least over a period of days—or in our case weeks. According to Angela, no crew that has tried has ever been able to stand such a schedule for more than a few watches.

My plan all along had been to position myself with the second watch. That way I could simply observe for the first two hours, after which I intended to row in the bow, so that nobody would actually see me or be aware of my ineptitude. However, as we pulled away from the dock I unwisely positioned myself on the bridge beside the commander, who quickly realized there was an empty seat on the starboard hull. She invited me quite jauntily to take it.

What was I to say after fifteen months of training—no thanks?

Within seconds I was in the seat, feet in the stirrups, pulling furiously on my big sweep oar. As fate would have it, I was seated behind Ryan Worth, a former collegiate rowing star and now a coach at the University of Tennessee. I am not exaggerating to confess that during the first twenty minutes aboard I clattered my oar off Ryan’s perhaps twenty-five times, each time offering up a plaintive little “sorry, Ryan”... “oh, sorry, Ryan”... “woops, sorry, Ryan,” etc.

It perhaps goes without saying that banging your oar off the oar of the rower in front of you is an unacceptable blunder, a no-no of the first order, among practitioners of this ancient team sport. Thus it was that about twenty minutes in, Ryan shipped his oar (which is to say drew it aboard without releasing it from its rigger), turned to me and said in a most patient and amicable voice. “Okay, I see where we’re at, Charlie. And what I normally take about three months to teach my freshman rowers I’m going to teach you in thirty seconds”—in other words, listen and listen good! And he proceeded to give me three or four fundamental instructions—about leg extension, about shoulder positioning, about pace and control and breathing—all of which I began immediately to incorporate into what I might presume to call my technique.

The next day, I got further instruction from Liz Koenig, a former varsity rower from the University of Rhode Island, also a coach, and within twenty-four hours was, if not exactly rowing like a pro, or even a “real” rower, rowing with sufficient awareness and capability that I was able to present a plausible impersonation of a guy on an ocean rowing team.

On Saturday night, we gathered at the Shelter Island Community Hall, a rustic old place without heat, where we met several dozen residents of the island, many of whom had seen the boat taking shape and had been invited to come out and meet the crew. One by one, we stood to introduce ourselves and to say something about our reasons for being here. Sylvain spoke about the need to challenge himself and to excel—said that by pushing the physical body he hoped to expand the spirit. Steve said he wasn’t sure what exactly had motivated him, except perhaps a desire to drive himself to the limit, in effect to see what was out there.

Aleksa spoke of a love of whales, Ryan of the pleasures of risk, Zach of a fascination with the unexperienced world. Tom said he had met the crew, had fallen in love with them, and wanted to consummate the romance. At sixty-seven, he also wanted to become the oldest person to row an ocean. Liz, meanwhile, said that as a twelve-year-old rower she had looked at the map and wondered if it would be possible to row the Atlantic—and was about to find out.

Louise had set out to row the Atlantic several years back, with another woman, and had had to stop just two days out of the Canaries because of her partner’s acute intestinal poisoning. “I love the sea; I love adventure,” she said with characteristic aplomb. “This time I’m going to make it.”

David said his motivation was to get us home safely and in one piece. It was no small order. Indeed, a question I’d been asked several times in recent weeks was what sort of safety equipment we would have aboard. “None,” I liked telling people, adding that we’d at least have a set of oars in case the engine broke down. We would also have life jackets and safety lines and survival suits, plus a pair of inflatable life rafts.

And we would have EPIRBs (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons). Until recently, I had never heard of such devices, which when activated send a distress signal to computers ashore, showing their location on a life raft or capsized boat, or with a swimmer. As I understood it, at least a couple of our crew would be bringing EPIRBs of their own, while the boat too would have a pair.

Privately, my concerns were less about the uncertainties of our travels than about the fateful certainties: exhaustion, salt sores, inadequate nutrition, plus what was invariably referred to as “extreme weight loss.” I also admit quietly to a lifelong neurosis about storms on water, which I had so far managed to suppress (or perhaps to face, as Mr. Jung might have seen it); and to an all-but-daily paranoia over whether or not my many months of training would hold up once I got out there on the main.

If there was a hitch in the weekend, it was (seen in retrospect) that our new captain was perhaps a trifle remote, reluctant to take the initiative and gather us in a group so that we could raise questions and discuss issues or information pertaining to the weeks ahead. But having little perspective and not wanting to seem impatient or overanxious, we let it go, allowing that Angela probably had too much on her mind for now, and that the time for more detailed discussion would come.

More importantly, we left Shelter Island with the deeply heartening memory of how Big Blue had coursed along the island’s east side after being launched, sitting as high and light as a water spider, touching speeds of nearly four and a half knots.² And how the following day on the north side of the island, with a little current beneath her, she had clocked out at nearly seven knots, a speed we imagined she would touch again easily with the trade winds behind us and the equatorial current underneath.

Back home, satisfied that the adventure was a go, we bought our air tickets for Morocco and began buying food and kit. At Shelter Island, David and his lieutenants put the finishing touches on the boat. During the first week of December, having done what they could for now, they took Big Blue apart, packed her into shipping containers, and hauled her to the docks in New Jersey, from where she would begin her voyage to North Africa.