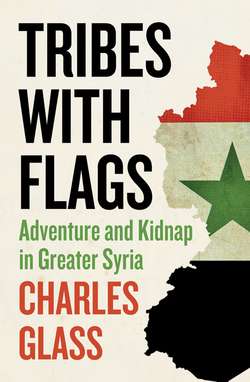

Читать книгу Tribes with Flags: Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria - Charles Glass, Charles Glass - Страница 13

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

NO-MAN’S-LAND

The old man had a long memory. “The French were bad colonialists,” he said. “In the Ottoman Empire, all peoples – Turks and Arabs, Jews, Muslims and Christians – lived in peace. When France came, it wanted to make a quarrel between them. They made minorities into enemies. They brought a lot of Armenians from Syria. They made them into soldiers and gendarmes. When they left, they took all the Armenians to Lebanon. Twenty-five thousand Armenians emigrated. They divided Syria – Hatay, Alawis in Latakia, Christians in Lebanon, Druze in the south. However many communities there were, they divided.”

He drew an imaginary map of the Levant with his index finger on the coffee-table, then pressed his finger down in the centre, near Beirut. “The quarrel in Lebanon is the result of French colonialism. Syria’s problems too come from the seed of French colonialism. For four hundred years in the times of the Ottomans, there had been no problems with the Alawis. France gave them the idea of having their own state. In Syria, the Alawis are ten per cent. The French gave them the military and other key positions, to use the minority against the majority. All Syrians were merchants and farmers, but the Alawis had the key military posts. Now they rule Syria with their ten per cent.”

Kemal Sehoglu was sixty-seven years old, a Turkish gentleman of the old school. A small, clean shaven, thin man with greying hair, he dressed comfortably in a turtle-neck sweater and tweed jacket. We were at his modern house on the banks of the Orontes in Antioch. He spoke softly in English, but was more comfortable in Turkish, French and Arabic. He suddenly switched to French.

“In the time of my youth, at the lycée, all the young men were opposed to the French occupation. It was our ideal to force them out. For all of us – Arab, Turk, Alawi, Sunni – passive resistance against French occupation went on for twenty years. All the people here wanted to annex to Turkey. There was the Arab minority which wanted to annex to Syria, but Syria had yet to become an independent state.”

Like all Turks, he believed Hatay had always had a Turkish majority. Arabs insisted they had been and remained in the majority. In Lebanon, Christians and Muslims made the same claims for their own communities. In the age of “majority rule”, demography was one key to power. Under the Ottomans, there had been only the rulers and the ruled.

For a year after the 1938 referendum, Kemal Sehoglu explained, Turkey and France maintained a joint administration over the “Republic of Hatay.” “Atatürk made Hatay un pétit état idéal pour tout le Moyen Orient. Because the state was a little artificial, they wanted to annex it to Turkey.”

Kemal Sehoglu was a farmer, who employed Arab and Turkish workers on his lands in the Amiq Plain. We met on my first day in Antioch. His sons had recently returned from universities in North America. Abdallah, whose nickname was Aboush, was twenty- seven and had graduated in 1983 from McGill University in Montreal. Mehmet, whose name was Turkish for Mohammed, was twenty-four and had finished business studies at the University of Denver in 1986. Mehmet looked and sounded like an American, and he was finding it difficult to readjust to life in provincial Antioch. When I asked him how a young man like himself met young women, he answered, “You don’t.” Then he laughed and added, “You forget about it. If you do start seeing someone, you express your intentions.”

“Have you expressed yours?”

“Not yet.”

Both Sehoglu brothers wore blue jeans, Aboush with a corduroy jacket and Mehmet with a pullover. They had picked me up at my hotel, just after I had endured breakfast, and driven me along the river to their house. Built in the 1960s, it was modernist and square, like many houses built at that time on the coast of California. Inside, the ceilings were low and the main rooms adjoined in an open plan, with exposed steps leading upstairs and walls without skirting or cornice. Glass doors at the back faced the garden and the river. They offered me a drink, but I settled for coffee.

Aboush was the heavier, more determined and more conventional brother. He was engaged to be married, had chosen to stay in Antioch to learn the family business and to succeed his father when Kemal Sehoglu retired. Mehmet was uneasy. Younger, thinner, he had enjoyed America too much to be content in Antioch. He – not unlike myself at his age and since – had no idea where he wanted to go or what he wanted to do. His brother clearly hoped Mehmet would settle down and stay at home.

“We have a summer place in Arsuz,” Aboush said. “A lot of people, let’s say the rich, of this area go there. It’s more comfortable. I mean, you can meet a lot of people, see girls in bikinis, everything. It’s easier there. In town here, it’s more difficult.”

“Do most young people who go away to be educated find they want to leave Antioch?” I asked.

“Most of them don’t come back at all,” Aboush said, glancing at his younger brother. “People who go to college in Istanbul, especially girls, usually get married there and settle. If they can marry here, they stay.”

“What is there to do at night here?”

“Nothing,” Mehmet answered.

“Usually,” Aboush said, “we get together with a few friends. We have a lot of business talks with my father. That’s it. It’s mostly business.”

“No movies?”

“In the last five or six years, going to the cinema is almost nothing, because of the video business. Some ten years ago, Antioch was more interesting. We had a lot more concerts. In the early eighties we had some terrorism, and people were afraid to go out to public places. Also, in the last four or five years, they’re not making good money in agriculture.”

“Are you going to stay?”

“Yes,” Aboush said firmly.

Mehmet said, “I don’t know yet. After I graduated, I came back here for seven months. Then I went to the States for a few weeks, but didn’t come back for nine months.”

I asked them about their education in Turkey. They had gone to an American secondary boarding school in Tarsus. “The school textbooks here do not mention the Armenians,” Aboush said. “There is nothing on the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. They go straight from the Ottoman Empire to Atatürk. They talk about Westernisation, but they don’t teach Western ideas.” He then told me what it was like to try to run a modern agricultural business in Hatay. “I went to a neighbouring province to discuss buying wheat from a farmer there. We had to sit outside on the ground. All the time we talked, the farmer had a rifle lying across his lap.”

When their father came in, the differences between the generations in Antioch became apparent. Although the father and his sons were close and respected one another, the boys had no interest in or recollection of the Ottoman period. Kemal Sehoglu had spent time in Alawi villages, where he had learned Arabic. He had studied under the French Mandate and spoke good French. His sons spoke Turkish and English. The things he mentioned – the Armenians, the resistance to the French, the mixed communities of Turks and Arabs, the changes wrought by Atatürk – meant nothing to his sons. In the same way, Mehmet’s anxieties about finding girls for casual relationships, discovering what he wanted to do with his life and deciding where to live, were alien to the father.

That night the Sehoglus took me to dinner at Antioch’s City Club, whose members were landowners and businessmen, in a spartan 1960s building trimmed in Oriental gilt. The dining-room was full when we arrived, nearly a hundred men at different tables, all in suits and ties, eating European-style food and drinking wine. Almost all the men were middle-aged or older and wore moustaches. There was only one woman, who sat at a table for two with her husband.

Mehmet talked again and again about his life in the United States and his worry about the future. He didn’t know whether to make films, work in journalism or television or go into business. All but the last meant leaving Antioch. Aboush talked about his fiancée, about settling down and, if the family business did well, moving it to Istanbul. A friend of theirs, who had joined us for dinner, had just completed his national service. When I mentioned a radio report that Turkey was blaming Syria for Kurdish attacks on military posts near the border, the friend said, “Don’t believe it. Those Kurds come from Turkey, not from Syria or Iraq. The government here won’t admit it, because they don’t admit there are any Kurds here.”

Whether or not the schools taught the young generation history, they would never escape its hold.

The grocer weighed each bag of vegetables in turn. He wrote the price of every item with a pencil on a crumpled bit of paper, the corn, beans, spinach, courgettes, aubergines, the flour, noodles and rice. He then added the figures on a pocket calculator. Not satisfied, he added them again by hand. This took even longer than that first calculation by machine. When his own arithmetic confirmed that of his calculator, he wrote the total. He could not have found a more time-consuming method, but on the barren stretch of road between Antioch and the Syrian border, he did not keep many customers waiting.

The driver loaded the bags of groceries into the back of his car, next to other provisions we had bought in town – razor-blades, soap, toothpaste, paper plates, a chess board and backgammon set. Sister Barbara and I sat in front next to the driver, a young man who lived near the chapel and hired out his battered old Mercedes from time to time. He turned the ignition key, pumped the accelerator, pulled the choke, swore under his breath and, after a short resistance, the car started. He put it into gear and drove onto the tarmac road, leaving the ramshackle grocery behind in a cloud of black smoke.

“I promised the children I would bring them news from their parents,” Barbara said, “but they have no word yet.”

The “children” were two Iranian refugees, boys aged eighteen and seventeen. They were living in the five-kilometre stretch of empty land between the Turkish and Syrian frontiers. Turkey used this border area to dump the people it did not want. Its other border posts, on the uncontested frontiers with Iraq, Iran, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria and Greece, lacked sufficiently large “no-man’s-lands” into which to deport people. If those other states would not accept the deportees, they would have to return to Turkey. At Cilvegözü, the Turkish authorities could leave people indefinitely in a no-man’s-land where the Syrians could not touch them, international aid agencies would not bother about them, and the world’s press was unlikely to see them.

“Are you a journalist?” an English-speaking border official asked me suspiciously.

“No,” I answered – truthfully in that I was not there in my capacity as a journalist, but as a travel writer.

Barbara negotiated with him in Turkish to permit us into the no-man’s-land to see “the children”. Our driver followed him in his official car through the border post, past the soldiers who guarded the gates that marked the end of Turkey. A dozen yards further on, at the left-hand side of the road, there was a small camp with a makeshift tepee of poles and plastic sheets, a wooden lean-to behind the tent, an abandoned rusting car with Syrian number plates and an open fire on which several men were boiling water in an old bucket. There were no trees and little other vegetation in the limestone hills. The place was, legally at least, nowhere.

When we stepped out of the car, I saw why Barbara had referred to the boys as “children”. The two brothers ran up to her like expectant puppies, excited to see her and running around both of us, ignoring the provisions we had brought, grateful we were there at all. When Barbara showed them the groceries, they lifted them out of the car and led us to their camp.

Ernest and Antonio Panusi had been living there for fifty-six days. A year earlier, they had fled Iran for what they said was religious persecution against Christians and to avoid military service in the war against Iraq. They had walked over the mountains into Turkey, which at first permitted them to remain without passports in Istanbul pending a British visa. Because they had twice visited England and had a sponsor there, they felt they had a strong case for entry. The British Consul in Istanbul denied the visa, so the boys were sent to this no-man’s-land. Their father and mother had gone to Ankara to find a country to accept their sons. “Now we are waiting,” Ernest said.

Two weeks earlier, three young women from Dominica had been living in the camp. Although the border guard said the women were prostitutes, it seemed the most the “children” did with them was play frisbee. The women had been there three months before they finally left.

It seemed the population of no-man’s-land was always in flux. When Barbara had visited a few days before, there were Ernest, Antonio and a third young man from Iran, an Armenian. Now the three Iranians shared the camp with two Egyptians, a Bangladeshi and a Gambian. They were as ragged a group of men as I had ever seen, lost in international limbo until they could contrive a way out. While there, they begged food from people crossing the border, accepted bread from villagers and hoped people like Sister Barbara would come to their aid. I asked the border guard if there were always people living there.

“Usually always,” he said.

“How do they usually get out?”

“If you don’t have a passport, we can send you out of Turkey. The illegal people ...”

“But, if you are here and you have no passport ...”

“Yes.”

“You don’t stay here forever. You leave somehow. How do they usually go? Do they go to Syria?”

“Yes. They go over the mountain to Syria, because Syria doesn’t have military people on the border. We have military people on the border. They cannot come back to Turkey, because we shoot them.”

“How long do people usually stay here?”

“Usually one month, or fifteen days or whatever. If they know this area, they go easily. But if they don’t know the area, and they have no passport, they wait until they get a passport. This is international land, not Turkey, not Syria.”

Barbara explained that Christians like Ernest and Antonio sought the help of the Church. Others, she said, paid money to shepherds and smugglers to sneak them into Syria. Once inside Syria, they had to avoid the police until they could find their way to some other country.

“Do the Syrians dump people here too?’ I asked the border guard.

“No,” he answered.

“One day,” Ernest told us, “the Syrian police came here, and they wrote down the names of all the people. But me and my brother, we didn’t give our names. There was one Iraqi boy. I told him, ‘Don’t give your name.’ But he gave his name to them. The next evening, the Syrians came back and took all the people whose names they had. They came again to take me and my brother by force, but we ran away. We don’t want never to go to Syria.”

“What happened to them?” I asked.

The border guard answered, “They took the three girls from Dominica to Syria. I think they went to Greece and then to their country. They were call-girls. The Syrians beat the Iraqi boy, because, you know, the Syrians don’t like the Iraqis.”

“The girls had passports?”

“Yes, but their visas expired,” the guard said. “Are you sure you are not a journalist?”

“I came here with the Church.”

The two Egyptians had been in prison near Izmir for twelve years. When they were released, the authorities gave them expired Egyptian passports. Because their passports were invalid, the authorities dropped them in the no-man’s-land. “Why were you in prison?” I asked one of them, a wiry man in his middle age, who answered in fluent English with an American accent. “For hash, man. I was taking it from Lebanon to Italy.” Then he whispered in my ear, so the border guard would not hear, “Can you believe it? For hash? These people are uncivilised.” He said their families had expected them home a few days earlier. “They just took us from prison to here. They didn’t give us a chance.”

Turning to the Gambian, a short, thin man, I asked, “Why are you here?”

“I lost my passport at the bus station in Istanbul, and I reported it to the police.” He showed me a receipt from the Istanbul police. “They took me to Ankara, and from Ankara they brought me here.”

The Bangladeshi gave his details to Barbara, telling her his name was Mohammed Abdul Mosabbir. When I looked at his Bangladeshi passport, it said his name was Shirez Jul Islam. His only problem was that he needed $100, because the Syrian customs officials required all non-Arab visitors to change $100 in foreign currency before they could enter the country. Mohammed, or Shirez, had left Turkey legally, discovered he could not enter Syria without $100 and could not return to Turkey.

The Armenian from Iran was a thirty-five-year-old electrical engineer. He spoke no English, so Ernest translated from Farsi. “He says he is here because Iranians coming into Turkey do not need visas. The Iranians can stay three months. His three months finished three months ago. The police caught him and threw him here. He can go to Syria, but he needs $100.”

“Does he want to return to Iran?”

“No. He says he wants to live as a free Christian. He wants to go to America or Europe. His sister and brother are in America.”

“Are they American citizens?”

“No, but his sister has a green card. She lives in Los Angeles, but he does not have an address or phone number. Also, he says they would not let him bring his baggage here, which he left in Alexandretta.”

“Where?”

“In a hotel.”

“Which hotel?”

After conferring for a minute, Ernest answered, “An Iranian home.”

“Where?”

“He does not know the address.”

“Does he have the telephone number?”

“No.”

Barbara and I took details of all the deportees, as well as letters from some to their families and embassies. We promised to contact their consuls, to bring them food and to let them know what we had been able to do. We believed that, when we returned, some of them would be gone. They would however be replaced by other victims of the absurd borders in a region which had done without them for centuries until the British and the French drew them across the map. As we walked to our car with their letters in hand, one of them shouted, “You are our only hope.”

The many travellers who had preceded me in the Levant over the ages, from Ibn Jubayr in the twelfth century to Lawrence of Arabia in our own, had not had to contend with borders. They were free to go all the way from Alexandretta to Aqaba without a border formality, customs search or visa. In the post-colonial era, I would have to cross frontiers to go into Syria, into Lebanon, back into Syria, into Jordan, into Israel and back into Jordan, just to traverse a Levant that was less than six hundred miles long. And at each border, there were those who could not make it, because their papers were not in order, because they did not have enough money or because, unbeknownst to them, their governments had offended the regime in one of the countries they wished to enter.

A friend of mine who was crossing into Lebanon from Syria met an Armenian who found himself caught years before without the proper papers, unable to enter either country. By the time my friend met him, he had resigned himself to his fate, opening a small shop between the two countries selling coffee and sandwiches to travellers during their long waits for permission to cross. The absurdity of this has not been lost on the inhabitants of the region, whose grandparents remembered fondly the Ottoman days when they could go from Beirut to Jerusalem and up to Damascus without seeing a single border guard. The Syrian film maker, Doureid Lahham, made a movie entitled Al-Haddoud, “The Borders.” Lahham, Syria’s Woody Allen, wrote and directed the comedy, and starred in it as a taxi driver who plied his trade carrying passengers across the frontiers. The driver, who believed official doctrine about Pan-Arab unity, did not recognise the borders. He endured ludicrous confrontations with officialdom each time he crossed. His yellow taxi was painted with black lines like a net across it, representing the artificial divisions of a land which had been united until 1919. It was a funny film, which sadly was all too true.

When Sister Barbara and I returned to Antioch, we telephoned the embassies and consulates of the men in no-man’s-land, none of which sounded surprised at the men’s plight. We sent their letters to their families, and I notified the Red Cross and Amnesty International. I had a feeling though that, if they were ever to escape, they would have to rely on bribery or cunning.

On the morning I was to leave Antioch, the Sehoglu family invited me to their house for breakfast. It was early, and Mrs Sehoglu was sleeping in. Kemal Sehoglu, Aboush, Mehmet and I sat around the family dining table for an early morning feast of tea, eggs, goat cheese, fresh yohurt, olives, hot Turkish bread and orange juice, served by a young Arab girl who wore a tight, dark dress and a thick, gold necklace. Kemal Sehoglu and I discussed the reasons why there were no Arabic schools, books or newspapers in Hatay.

“You must remember,” he advised me, “they do not teach Turkish in Syria or Bulgaria, where many Turks live. Perhaps ten per cent of Syrians are of Turkish origin, but they cannot study Turkish.” He asked the girl in Arabic to give me more tea, telling me, “I learned Arabic in the villages, but I forget.” He proceeded to speak to me in Arabic, slowly so I could understand much of it, for fifteen minutes.

The Sehoglus found a driver, who assured them he spoke Arabic, to take me to Samandag, near the Roman port of Seleucia Pieria. According to Aboush, Samandag was a disappointing attempt to create a tourist resort. Its beaches were covered in tar, and the only hotel had become a barracks. The main reason it failed, he said, was the opposition of local smugglers who thought tourism would inhibit their business activities. “There are also sharks,” he added. I thanked the Sehoglus for their kindness to a stranger and gave Aboush a copy I had borrowed of A History of Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. The book said that Mark Antony and Cleopatra came to Antioch in 37 BC and that Antony’s gift to his Egyptian lover was all of Syria and Palestine, land that would be given to and taken from many people in the centuries that followed. Cleopatra lost it after six years. A map in the book showed an unbroken Roman road along the coast from Alexandretta into Palestine. In our time, the coast road ended in the brush just south of Arsuz. It began again at Samandag, and there were many borders between there and Sinai, at least one of them impassable.

As we drove out of Antioch, dark clouds crept over the mountains and rain began to pour. A few miles outside the city, the road to Samandag became a gravel path which wound through small farming villages and fields of barley. After nearly twenty miles of slow driving, during which I discovered the driver knew only a few words of Arabic, we approached the coast. There we found “Samandag,. Pop. 27,300.” Samandag was as ugly as the countryside was beautiful. The main road through the city, which we followed in the direction of signs pointing to the Plaj, was lined with petrol stations, garages, timber-mills and car parts shops separated at intervals by small orange groves and a bridge over a stream.

In the centre of Samandag, there stood another statue of Atatürk, this time in tails and cape. Larger than life, he was doffing his top hat with his right hand like a magician ready to produce a rabbit. Past the main square towards the beach were scores of new, single-storey houses, square and unornamented. The closer we came to the sea, the older the houses became, most of them red or white stucco cottages, a few with second storeys and small vine-covered terraces.

We reached the shabby seafront to find it much as Aboush had described. We could see neither the smugglers nor the sharks, but there were a few fishermen using dynamite, tar-covered sands and an abandoned, rusting motel. Waves washed the deserted beach, where a few small boats waited empty for fishermen to take them out. In the great campaign to resist the rising tide of tourism, Samandag was winning.

The Roman ruins of Seleucia Pieria were a few miles to the north at Cevlik, where the ancient foundations of stone piers stretched from the shore and disappeared in the surf. Here the Orontes flowed into the sea, its deposits over the centuries filling the ancient harbour so that, by the time the Arabs arrived in the seventh century, it was barely usable. Modern Cevlik was a dull seafront village with a few commercial buildings, a post-office shack and a camp ground near a new, little-used marina. I walked through a long passageway cut through the rock which the guide books said was a Roman aqueduct built by the Emperor Vespasian. Without water, it seemed more like a coastal defence which allowed soldiers to move without being seen from the sea.

Disappointed with Samandag, with Cevlik and with the ruins, I asked the driver to take me to the border. Rain was still coming down when we made our way back through Samandag. Suddenly, just beyond the town, a police car drove in front of us and ordered the driver to stop. When he got out to talk to the two uniformed policemen, I remained in the front seat of the car reading a book. I was still reading when one of the policemen tapped on my window.

He spoke to me in Turkish, but the only word I could understand was “passport.” I handed him my passport, and he took it to his colleague in the police car who appeared to read my passport details over the radio. The driver and the two policemen resumed talking, and I went back to reading. About ten minutes later, another police car arrived. The officers inside were dressed somewhat differently from the first two. Perhaps they were more senior. They spoke for a little while to the other policemen, and one of them walked over to me. He spoke to me in Turkish, but I said nothing. He called the driver, who made a pretence of translating my Arabic into Turkish.

They went back to the two police cars, spoke on the radios and conferred among themselves. All of them looked solemn. I went back to reading. Another ten minutes or so passed, and I slowly became afraid that, for reasons I might never understand, I would be arrested in this lonely southeast corner of Turkey. The longer I waited, the more difficult it became to read. I stared at the pages, hoping the police inquiry would end quickly. A few more minutes and one of the policemen marched to my window. Would he arrest me for treading through Vespasian’s aqueduct or venturing through the failed tourist resort of Samandag?

He tapped again on the window and reached into his pocket. I looked into his face, wondering what he meant to do. He stared back at me. Then he handed me my passport without saying a word. As we left Samandag, I relaxed.

I learned much later that after my departure the police in Antioch had interrogated some of the people who met me there. The same thing would happen in Syria.

It was early afternoon when we reached the riverside village of Cilvegözü, which gave its name to the border post. Cilvegözü was little more than a hamlet of small farmers, who derived additional income from the smuggling which began as soon as the border was laid next to it in 1939. In the late 1970s, most of the smuggling was of consumer goods from Syria into Turkey. With Syria’s chronic shortages in the 1980s of foreign exchange and simple consumer items like cooking oil and washing powder, the traffic in household goods was going the other way.

The flow of drugs had also reversed itself. Before the opium eradication programme in Turkey and the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, the drugs had gone from Turkey, often by truck, hidden in bags of cement, through Syria to Lebanon. In Lebanon, the opium was processed and exported by air, sea or land. The opium was now grown in Lebanon and sent through Syria and Turkey on its way to growing markets in Europe and America. Perhaps the destruction wreaked by the heroin repaid the West in some small part for the harm done by all the weapons it had poured into the Levant. Evil for evil. At night, for a price, a shepherd or farmer from Cilvegözü and other villages on both sides of the frontier would guide a smuggler over the mountains across a border which for them was little more than a source of profit.

For the traveller, the border crossing at Cilvegözü, like all the other border crossings in the Levant, was a nuisance designed to cause him maximum inconvenience. Cars were not allowed to carry passengers to the customs and immigration buildings, so young boys were waiting near the car park outside the border post to carry luggage. One of them wrested my two bags from me and carried them the hundred yards to the modern immigration post. Inside the tidy office, there was an orderly queue of only three men waiting to present their passports to the border policeman seated behind the counter. The policeman wrote down the details of each passport in a large ledger. He asked questions, wrote down answers and asked for other documentation, while each man in turn searched his pockets for the right bit of paper. Processing each traveller took fifteen minutes, and I waited patiently while other border policemen strolled nonchalantly behind the counter, apparently with nothing to do.

When my turn came, the policeman took my passport, looked at it and stood without saying a word. He walked to a telephone in another part of the room, spoke for several minutes, apparently making references in Turkish to my passport, and then returned to his desk. He noted all my passport details in his book and handed me the passport. This had taken twenty minutes. I walked out of the building wondering where to go next. My young porter tugged my sleeve, and I followed him to a tiny office nearby. He handed me several cards to fill in and led me to several more offices, in one of which my bags were searched. Several officials later, a policeman told me I was free to go. Go where? Without a car, it was nearly a five-mile walk through the no-man’s-land to the Syrian border post at Bab al-Hawa. The boy picked up my bags and walked me to a small, blue Volkswagen van with most of the seats torn out. He threw the bags into the back, and I tipped him. Without his help, I have little doubt I would still be there.

While waiting for the van to fill with passengers, I took a radio out of my bag and heard on the BBC World Service a report on Turkey’s application to join the European Community. “Turkish standards are ready for EEC standards,” a Turkish official was saying. “Community membership will be a guarantee for democracy, as in Greece, Spain and Portugal.” Mark Sykes would have agreed. Although his 1916 understanding with the Russians and the French, the Sykes-Picot Agreement, created the borders which still plagued the Levant, he believed the Turks would make good Europeans. He thought this more natural than any union of Turks and Arabs. In his account of a trek with dragoman, cook and six other servants through the then-borderless Ottoman Empire in 1902–3, Dar-Ul-lslam: A Record of a Journey Through Ten of the Asiatic Provinces of Turkey, the spokesman of the British Empire wrote:

In speech the Turks are expressionless, quiet and laconic, using few gestures or similes [sic]; but with Arabs it is almost possible to follow an argument while not comprehending a word of the language. I have heard a person, who could speak with authority, state there could never be an amalgamation between Turks and Arabs, and I think there is no doubt this is true. A Turk will understand an Englishman’s character much sooner than he will an Arab’s; the latter is so subtle in his reasoning, so quick-witted, so argumentative and so great a master of language that he leaves the stolid Osmanli amazed and dazed, comprehending nothing. The Turk is not, truth to tell, very brilliant as a rule, though very apt in assuming Western cultivation. This may sound extraordinary but is nevertheless true so far as my experience carries me. Every Turk I have met who has dwelt for a considerable period in any European country, although never losing his patriotism and deep love for his land, has become in manners, thoughts and habits an Englishman, a German or Frenchman. This leads one almost to suppose that Turks might be Europeanised by an educational process without any prejudicial result, for at present they have every quality of a ruling race except initiative, which is an essentially European quality.

Twelve years after he wrote these words, Mark Sykes and fellow servants of two other European empires, France and Czarist Russia, drew the modern boundaries of the Ottoman Empire without consulting a single Arab or Turk. This became known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Two years later, having heard from the leaders of the Arab Revolt, Sykes regretted what he had done. In October 1918, he wrote that Britain should “foster and revive Arab civilisation and promote Arab unity with a view of preparing them for ultimate independence.” He was too late. Sykes died a few months later in Paris as the peace conference that would divide Syria began.

After half an hour’s wait at Cilveögzü, two Syrian families on their way home managed to fill the van, and we paid the driver for what I had assumed would be a lift to the Syrian side. We passed a mosque on the left and, on the right, a statue of Atatürk bidding us farewell. The driver went all of a hundred yards, then stopped his van at the gate which marked the end of modern Turkish territory. There three soldiers in starched uniforms were standing at attention.

The driver told us to get out of the van and wait for a second vehicle to come from the Syrian side. I walked towards the refugee encampment, where the “children” and their friends were sitting around the fire. One of the soldiers refused to let me go any further, so they came over to me. I told Ernest and Antonio that Sister Barbara and Father Ferrari had spoken to their parents, who were staying at the Franciscan rectory in Ankara and were trying to find an embassy to give them a visa. The two brothers were still hopeful, telling me not to worry about them. Antonio said, “We’ll see you in England.”

I told the Egyptian we had mailed his letters and that the Egyptian Embassy said it would try to issue him a new passport. He complained that if he remained there much longer, he would ask to return to prison, where, “At least, I had a roof over my head.” I told the Gambian that Hind Koba in Alexandretta, who as British Consul represented Gambian interests in Turkey, had promised me she would help him. He showed no reaction.

The English-speaking border guard who had been with us before suddenly walked up to me. “Did you do anything for them?” he asked, with what sounded like genuine concern for the deported men.

“Not enough,” I said. “If their embassies don’t help them, what will happen if they escape into Syria some night?”

“I don’t know what will happen to them then.”

I rejoined the two Syrian families, with their small children and their bundles of groceries which they hoped to smuggle home, and we boarded an old, rusting Syrian bus. I waved out of the window to the lost souls of No-Man’s-Land, who waved back and shuffled through the dust to their camp. The driver collected our fares and started the five-mile journey through the stony foothills to the Syrian side. The last thing I saw before we rounded the bend was a large sign, which warned,

Yavu Yavu

Slowly Slowly

EXPLOSIONS