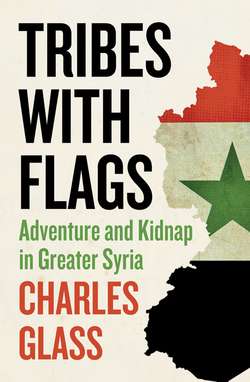

Читать книгу Tribes with Flags: Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria - Charles Glass, Charles Glass - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

THE LEGACY OF ALEXANDER

Three dogs pulled and tore the flesh from the corpse. The lamb’s rib-cage was already bare, and still they clawed at the body and snatched lumps of meat with their jaws. They had opened the animal up from its soft stomach, and the wool was stretched aside to expose the food within. The entrails were mostly eaten, but the lamb’s head was untouched. Its eyes were open and blank. The dogs’ paws, their jowls and the hair around their eyes were stained, like the ground, dark red. One dog growled for a moment to warn another not to tread on its portion of the dead prey. Then it silently rejoined the feast, the grim work of devouring what each could of the lamb before they abandoned its carcass to the flies.

The black and white mongrels and the lamb were the only signs of life or death in the barren limestone hills. We were on the highway to Alexandretta, and the driver had stopped the bus and gone into a solitary hut just off the road. No one asked why. This was not, I would learn, unusual. Buses did not keep schedules here, and drivers made their money from more than the transport of passengers. They delivered food and parcels, they carried letters, they smuggled gold, cigarettes, coffee, refugees, drugs and weapons across borders. “A bus like this,” one man explained, “can support a whole family.”

Several passengers including myself had used the unscheduled stop to get out and stretch our legs. The sun was going down. I walked several yards from the bus to be alone. I was watching the dogs when another passenger approached me. “Do you have a degree?” he asked me in English. His accent was slight. He seemed to be in his mid-forties. He wore a grey zip jacket, khaki irousers and old, unpolished shoes. On his lip was a thin moustache.

“I’m sorry … ?” I said.

“A degree in something, from a university?”

“Yes, in philosophy.”

“Falsafi,” he said in Arabic. Then in English, “That’s very good.”

“And you?”

“Mechanical engineering.” “Something practical, not like philosophy ...”

“I have a textile factory in Damascus,” he said. “I’m here to buy materials.”

“Are they better here in Turkey than in Syria?”

“Ha,” he laughed. “You cannot find them in Syria. Anyway, this is Syria.”

“Surie al-Kubra?” Greater Syria, I asked in Arabic.

He laughed again, patting my back. “You speak Arabic?”

“Only a little.”

“Smoke?” He held out an open pack of Marlboro. “You have a family?”

I nodded.

“I have three children,” he said proudly.

The Syrian textile manufacturer had established that, for the duration of the bus journey, we belonged to the same tribe. We were both non-Turks, both had university degrees and both had children. It was bond enough to keep loneliness and the dogs at bay on the dark, perilous road, in a bus crowded with forty strangers, in a land that was not ours. The driver came out of the hut, carrying a small package. We followed him onto the bus. Without discussion, the Syrian took the empty seat next to mine. The bus coughed and bumped its way towards Alexandretta, while the Syrian and I talked into the night.

It was nearly midnight when we reached the edge of Alexandretta, a port town whose form it was impossible to distinguish beyond the glare of the highway and car lights. When we passed a sign which said in Turkish and English, “Iskenderun, pop. 173,700”, I asked the driver to stop. Handing me down my bags and typewriter, the Syrian told me to call him when I reached Damascus. I agreed, knowing it was unlikely. We would not need each other there, where he would be home among his people, where I had friends, where our common levels of education and fatherhood counted for nothing. Alliances here lasted only as long as the need for them, a truth we implicitly shared as he reached his hand out the window to shake mine in farewell. Now alone at the side of the road, I watched the red lights of the bus disappear into the warm Levantine night.

The first strains of the music woke me early. The only sound which should have disturbed the peace of Friday, the Muslim sabbath, was the muezzin’s call to prayer. The sound coming through my window was from a brass band, whose music sounded like a cross between a Handel anthem and a John Philip Sousa march. I went downstairs to the lobby of the Hatayli Oteli and looked out the front door towards the seafront. A parade of what looked like half the population of Alexandretta was marching along the corniche like irregulars at the end of a long campaign. Women carried wreaths and men wore ribbons, and all walked out of step with the triumphal music.

Was this, I wondered, Turkey’s national day? Had democracy been restored? Perhaps war had been declared? I asked the porter what was happening. Discovering we had no common language, I pointed at the parade and tried to look puzzled.

“Polis Bayram,” he said. “Bayram” was Arabic, and apparently also Turkish, for “feast” or “holy day”. “Polis” was Turkish for “police”, and pronounced the same way. I learned later in the day that Turkey was celebrating the anniversary of the founding in 1845 of the Ottoman Police. Everyone in Iskenderun seemed to be wearing a small green and red paper badge, with the Turkish crescent and star in its centre, saying, “10 Nisan Polis Günü”. Despite the obvious enthusiasm of the crowd for the festivities, there was something strange about it. Turkey was the first country I’d known to celebrate the creation of a police force. It seemed to me that the establishment of the police was an admission of failure, an acknowledgement that man was inherently evil and had to be controlled, a cause for regret rather than joy.

No one in the hotel spoke anything other than Turkish, but a young man and young woman behind the reception desk struggled to recall a few words of English. I wanted to telephone the tourist office to see whether I could obtain a car and guide to show me around Alexandretta. I telephoned the number listed in the Fodor Guide, which turned out to be the house of an irate woman speaking only Turkish. The receptionists found another number. It was the tourist office, but the man at the other end spoke no English. The receptionists suggested I walk to the tourist office and assured me someone there would speak English. In a way, they were right.

The hotel porter led me along the wide seafront drive, where drab concrete offices and shops faced the port, to the tourist office on the ground floor of an old building. Inside, a man in a tweed jacket and necktie introduced himself as Mehmet Udimir. He spoke a few, very few, words of English. He said Udimir meant Iron, and made a fist to show it. He was the only person in the tiny, cavern-like room. I explained I needed a guide. He handed me a pamphlet.

Iskenderun is situades atthe foot of the Amanos mountains. It’s about 5 km. wide. The elimate is temperate, and during the winter it is like spring … The raining season is winter. The surrounding mountains are covered with fir forests. Iskenderun is one of the most important port-towns of Turkey. Iskenderun was founded (Alexandrietta) by Alexander the Great after his victory at Issos, The town, in order to distinguish it from Iskendiriye (Alexandria) in Egypt, was given the name of Alexandria Minor in the 17the century …

“No, no,” I said. “Not this sort of guide. I need a man who speaks English, to show me the historic buildings.”

“Okay,” he said, standing up, walking outside and locking the door behind us. I had acquired a guide.

“You see church first,” he said, turning left and leading us away from the seafront into the town. “Church is very old.”

“How old?”

He thought for a minute, but could not give me the date in English. He took a pen and paper out of his pocket and wrote. He handed me the paper. It said, “1901.”

“Very old,” I said.

“Then you see library,” he promised.

“How old is that?”

He wrote again on the paper and handed it to me. “1868.”

We had not reached the relics of Alexander’s invasion, but we were headed, as far as time goes, in the right direction. We walked past the Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation, but he did not stop there. He merely pointed at it, saying, “Church very old,” and continued across a small, leafy side road to the library. Mehmet Udimir took me into a shaded courtyard behind a stone wall and into a building which looked as though it had once been a large private house on two floors. We walked upstairs, passing reading rooms where schoolchildren were studying. On the walls of each room were portraits – some of them photographs, others prints of oil paintings – of the father of modern Turkey, Moustafa Kemal Atatürk. An Islamic historian in Beirut had once told me, “Atatürk was a man of contradictions, even in his name: Moustafa means ‘chosen one’, Kemal means ‘perfection’, Atatürk means ‘Father of the Turks’. Yet he was neither chosen nor perfect nor even a Turk.”

We walked into an office, and I sat down on one of three wooden chairs facing a large desk. Mehmet sat behind the desk and under another portrait of Atatürk. This painting was almost life-size, in full colour, and showed Atatürk in white tie and tails, his arms casually folded, looking handsome and rather like Noël Coward. His red hair, blue eyes and reddish lips looked anything but Turkish, and it was little wonder his enemies had accused him of having a Greek father and a Jewish mother.

An ancient man, wearing an old, baggy suit, shuffled slowly into the office carrying a tray with glasses of tea on it. His facial features were like a Mongolian’s. He said nothing to either of us, but put the glasses on the desk. It was clear that Mehmet Udimir was not merely the director of tourism in Alexandretta, he was also the chief librarian. I felt as though I’d strayed into one of those small American towns in which the same man, simply by changing hats, served as policeman, judge, fire chief, mayor and coroner. I was certain that if I asked Mehmet to take me to the head of the chamber of commerce, we would walk into another office, where he would sit down behind another desk and another old man would bring us tea. That way, I could confirm the answers to my questions to the tourism director with quotes from the chief librarian and the head of the chamber of commerce. It was an old journalistic trick, but one Mehmet inadvertently prevented me from playing by never telling me anything.

Another old man, better dressed and more distinguished, came into the office. He must have been in his late sixties, and he had a trim moustache. After shaking my hand, he sat down. “I was his teacher,” he said in English, indicating Mehmet. “I am free now.”

“Retired?”

“Yes,” he said. “I come to see Mehmet one day each month.”

Mehmet smiled and appeared to ask him what he had said. They then spoke for a minute in Turkish.

“And you?” the retired teacher asked. “You are tourist?”

“Sort of,” I explained. “I am writing a book.”

“You are going to Antakya?”

“Yes.” Antakya was Turkish and Arabic for Antioch, the city in which the disciples of Christ were first given the name “Christians”.

“In Antakya, you are to look at two places famous, the church and the museum.”

The first old man returned with more tea, served as everywhere else in the Levant hot in clear glasses with no milk and much sugar.

We were talking when a thin young man with black hair, a short black beard and a hawk’s nose, came in and sat down. The retired teacher told me the young man had recently returned to Alexandretta from Istanbul after the death of his father. The father’s restaurant had closed, and he had come to arrange his family’s affairs before returning to Istanbul. The young man, in his mid-twenties, spoke a few words of English, rather like Mehmet. He offered to help me find my way around Alexandretta. His name was Munir. He told me he was half Turkish and half Iranian.

Friends in Beirut and Damascus, I said, had given me the names of people to see in Alexandretta, traders named Makzoumé and Tanzi. Mehmet tried to telephone Tanzi for me, but there was no reply. He could not find a number for Makzoumé, so he asked Munir to take me to the Makzoumé Shipping Company nearby. We finished our tea, and I thanked the director of tourism and chief librarian for his help. He and his former teacher said they would see me again.

It was a short distance to Makzoumé’s offices, back in the direction of the sea. The offices of the Makzoumé Shipping Company were more European than Oriental, with fitted carpets, modern furniture and paintings. There was no old man with tea, but there was an attractive secretary at a desk in an outer office. She showed us into Makzoumé’s inner office, where we sat in silence while he finished making telephone calls. He was an old man, a little overweight and well dressed in woollen trousers and a cardigan. He looked more European than Turkish or Arab, and, as it turned out, behaved more like a European than a Levantine.

While we sat waiting, he spoke on the telephone in Turkish, French and Arabic. When he finished, he asked me why I was there. He was the first person I met in Alexandretta who spoke fluent English. I was hopeful that he could guide me through my first day in his city. I explained that mutual friends, who had been his neighbours when he lived in Beirut, had given me his name as a man who would help me in Alexandretta.

“I don’t think so,” he said. He could do nothing, because he was leaving for Europe the next day. “Perhaps this young man can help you.”

“He is trying,” I said. “But he has been away from here for years, and he does not speak English.”

“I am sorry,” Makzoumé said, the resignation in his voice betraying more relief than regret.

As we left his offices, he called out, “You could try the British Consul.”

Munir and I walked to the Catoni Maritime Agencies, an Ottoman stone building which backed onto the sea and had for years served a secondary purpose as British Consulate in Alexandretta. The front room was a shipping company and travel agency, in which a woman was preparing airline tickets for a customer seated by her desk. I asked where we could find the British Consul.

She indicated a door to another office, and Munir and I went in. The first sights to greet us on entering were three large portraits: in the centre, of course, was Atatürk, to his right was Queen Elizabeth and on his left was Prince Philip, who in Turkey, if nowhere else, was never referred to as “Phil the Greek”. The portraits of the British queen and her husband, bedecked in medals and ribbons, were nearly as dated as that of Atatürk, obviously made many years and many chins ago. Beneath the portraits sat a soberly dressed middle-aged woman, who looked as unassuming as the luminaries behind her were grand. When she saw us, she looked up from her desk with its small British and Turkish flags and smiled. “May I help you?” she asked.

She understood immediately when I explained the purpose of my journey and why I had begun in Alexandretta. She was just old enough to remember that the province had been part of Syria until 1939, although too young to have been born when the whole region was united under the Ottomans. Hind Koba, MBE, had been Her Majesty’s Consul in Alexandretta for nearly thirty years. I told her that I had introductions to only two people in Alexandretta, Makzoumé, who had not been helpful, and Abdallah Tanzi, whose telephone did not answer.

“Abdallah Tanzi,” she said, “is my brother-in-law. We live in the same building.” She thought it would not be difficult to find him. She promised to make appointments with a variety of people who would give me some idea what Alexandretta was like and how its life had changed. Her first call was to a lawyer named Kavak, who said he could see me then.

Walking through the streets, which were becoming more crowded as the morning grew late, Munir used his few words of English, gestures and the gift of an expressive face to tell me that his life was unhappy. He was a Shüte in a Sunni Muslim country. He was half-Iranian in a land which distrusted Iran. His father was dead. He owed taxes on his father’s restaurant, which had closed as a result. He had to care for the rest of his family in Alexandretta, and he yearned for the cosmopolitan life of Istanbul. “Maybe one year,” he said. “Maybe two.” Then he could leave Alexandretta again for the pleasures of the north.

We found Kavak’s office in a modern, if run-down building, up two flights of stairs, past various shops selling women’s clothes and building supplies. A dark-haired man in his mid-thirties opened the door marked “avukat”, introducing himself as Yalçin Kavak. We followed him into a room filled with law books and a large desk covered in papers. There seemed to be no picture of Atatürk, but a small staff displayed a Turkish flag. We had been squeezed into the little office for a few minutes when Kavak invited us to lunch. Munir had to leave for an appointment, but said he would see me later at Mehmet Udimir’s library.

Kavak took me to what was called a “popular” restaurant, the Büyük Ekspres Lokantasi, for “typical” Turkish food. We found ourselves in a large rectangular room, with simple wooden tables and chairs. The walls were bare except for the mandatory portrait of Atatürk. Neither the fan nor the lights overhead were on. We sat at a table near the front window. There was no menu. A waiter asked us what we wanted. When we asked what was available, he told us to come into the kitchen. The kitchen was divided from the dining- room by nothing more than a glass-fronted refrigerator and a food warmer, both chest-high. In the refrigerator were huge chunks of raw meat, lying in trays of blood, chops, beef, spiced minced meat called kofta, all ready for grilling, and salads and cold vegetables. The warmer was full of stews, cooked vegetables, meat pies and dolma, stuffed vegetables like vine leaves and courgettes. Kavak advised me to have a kebab of beef and aubergines, with yogurt, hommous and cold artichokes to begin. The waiter looked pleased with the choice.

The restaurant was filling up with working men, businessmen and a few families with children. The waiter brought me an Efes beer, a Turkish lager apparently from Ephesus, which was cold and tasted good. Between bits of food and drink, we talked about Turkey, religion, politics and the Arab world which Turkey had once ruled and had since forgotten.

“Today in Turkey,” Kavak said, “there are some conservative people who dream of the return of the Ottoman Empire, but the military wants democracy. Meanwhile, Russia is working underground here. It wants to take advantage of Turkey.”

A minute later, he said, “Atatürk was from Thessaloniki. He was very keen on Europe and on democracy. It was very hard for Turks to accept a democratic way of life. Eighty per cent of the people think this country should be European.”

Eating my eastern food, I found it hard to think of this country as a part of Europe. All the food was good, similar in substance to that in the rest of the eastern Mediterranean, but spicier and prepared slightly differently. The hommous, a familiar paste of mashed chick-peas and tahina, was made in a Turkish way, covered not only with olive oil, as in Lebanon and Syria, but with ground red and black pepper, whole green chilli peppers and slices of tomato. As in Syria, we scooped it up with warm, flat bread, but the bread was thicker than Arabic bread and had seeds on top. Delicious as the food was, in Europe it would always be “ethnic”.

Turkey nonetheless had applied to join the European Community. Kavak said the prejudice against Turkish membership was unfair, particularly when it was based on history. “There were problems in 1914. There was persecution of the Armenians and Assyrian Christians, but it is wrong to blame Turkey for the actions of the Ottoman Empire. We do not blame West Germany today for Hitler.”

I asked him about the city. “Iskenderun,” he said, using its proper name in both Turkish and Arabic, “has changed. It was a famous seaport, very deep, for big ships. It is close to Iraq. It has been very important in supplying Iraq in the war against Iran. Many people came from eastern Turkey to settle here. We have the biggest iron and steel factory in Turkey, ISDEMIR.” ISDEMIR was the acronym of the state-owned Iskenderun Demir Celik. “The factory has 16,000 employees and 2,000 managers. This is 18,000 people plus their families. All were brought from outside.”

“Has this shifted the population balance here in favour of Turks?”

“Until 1964, perhaps sixty per cent of the people here were Arabs and forty per cent Turkish. The Arabs were mainly in agriculture and fishing. Today, the population of Iskenderun is approximately 175,000. Twenty-five per cent maximum are Arabs. The other seventy-five per cent are Turkish, with some Kurds.”

“Did they all come here for work?”

“The eastern cities in Turkey do not offer enough. People have to come to the western cities to progress. Even me, I was a lawyer in the east, in Merdin. I was doing well there, but I had to come to Iskenderun.”

“Is there any Syrian influence here?”

“If you study Hatay,” he said, using the Turkish name for the province, “you must look at Syria. In Syria, I think twenty-five per cent of the people are Alawi, forty-five per cent are Sunni and thirty per cent are Christian, including Armenians and Assyrians. The man who became president of Syria is Alawi. He didn’t come to power democratically. He wants to remain president. He puts Alawis in important positions, as military commanders and security police. He is afraid. Of what? Who is against him? The Muslim Brothers, the Iraqi Baath Party. Because of this opposition, twenty-five per cent of the population is not enough for him. This is why, I heard, clever young Alawis from Samandag, in the far south, are being taken to study at the university in Damascus. They study medicine or go into the military and don’t come back.” The Alawis are a dissident sect of Shiite Muslims, who live mainly in the hills along the sea between northern Lebanon and Alexandretta.

Kavak said he had been active in politics. “Before 1980, I belonged to the Social Democratic Party, the democratic left. In Turkey, the Communist Party is forbidden. This is why some people who are not social democrats, but Marxists, work in the Social Democratic Party. They work together and support each other. If you want to succeed, you have to cooperate with the communists. I did not want to. Also, with my work, I don’t have enough time.”

When the waiter brought us the main course, I reflected that Kavak was an unusual man, though just how unusual I had yet to discover. He looked like a conventional lawyer in his dark three-piece suit, his hair combed neatly back, his face shaved. Yet he had mentioned things that were banned in Turkey: 1914, Armenians, Kurds, Alawis who looked to Syria. In official Turkish doctrine, no massacres took place in 1914; there were no Armenians; Kurds were “mountain Turks” Alawis were Turkish without ties to the Arab world. Denial of reality was official policy.

“I was raised a Muslim,” he said, “but I became a Christian in 1970.”

The surprise on my face was difficult to conceal. In all the years I had spent in Muslim countries, I had met only one convert from Islam to Christianity, a professor of philosophy at the American University of Beirut. I had met many converts who had gone the other way, from Christianity to Islam. In Cairo, I knew an American Jew who had become a Muslim. Western Protestant missionaries in 19th-century Syria concluded after many failed attempts that Muslims could not be converted to Christianity, so they concentrated instead on turning eastern Christians, Catholic and Orthodox, into Protestants. Kavak was the first Turkish Muslim I met who had become a Christian. He was not to be the last.

“In 1914,” he recounted, “the grandfather of my father was murdered. It was at the time of the troubles. A Muslim mullah took his son, my grandfather, and raised him as his own son, as a Muslim. Our family were all Muslims. My mother was an Arab Muslim, and we spoke Arabic at home. We read the Koran in Arabic.”

“How did you change?”

“One of my family was a candidate in the elections when I was a teenager. His opponents asked people in Merdin, ‘How can you vote for an Assyrian Christian?’ We did not know what they meant. So, we went to Assyrian villagers, who told us, ‘Your family are Assyrian.’ They told us we were related. Then I learned that my great-grandfather had been killed because he was an Assyrian, when many Assyrians died along with the Armenians.”

“Was that reason enough to become a Christian?”

“When I was at the university, studying law,” he said, “I read the Bible and the Koran. Mohammed was a great leader and a clever man, but I did not find him to be a real prophet. I think maybe some Jewish people helped him, because the Koran is very close to the Old and New Testaments.”

“Is your wife a Christian?”

“She is Turkish from Istanbul,” he said. “I explained my situation to her very clearly before we were married, and she accepted it. She is ready to be baptised, but I want her to study first.”

“Is religion important here?”

“Many educated people here are not Christian, but they are not really Muslim. They don’t go to the mosque and don’t like Islamic life. It is something that exists only on the identity card, Muslim, Christian or Jewish.”

“Identity cards still state your religion? I thought this was a secular state.”

“The Turkish Republic was founded in 1923,” he said. “This is not a long time for a state, especially for a people changing their system from Islamic to secular. But we have come a very long way.”

How far had this corner of Turkey come, separated as it was from the world to which it had belonged for millennia? In 1918, when the Turkish army retreated from Syria north into Anatolia, it abandoned the province of Alexandretta, the harbour at Alexandretta town, the city of Antioch on the banks of the Orontes and the fertile fields, mountains and forests in between, its Arab population and its Armenian and Turkish minorities. For the next twenty years, it was divided from the rest of Turkey, ruled by the French as part of their League of Nations Mandate over Syria. In 1938, France held a referendum on the province’s status and created the so-called Republic of Hatay. A year later, the French gave it back to Turkey. Since then, it has been cut off from the rest of Syria. It seemed doomed in this century, as a frontier province of states to either its north or south, to be separated from at least half its historic self.

In the centre of Alexandretta’s seafront, near the port, lay a large marble plaza. On it a giant black monument, shaped like a wave about to sweep away the town and all its people, appeared to rise out of the Bay of Alexandretta. On its high summit stood two life-size sculpted figures: a woman holding an olive branch and a soldier standing to attention. Between them a large Turkish flag, secular red with the white crescent and star of Islam, fluttered in the breeze. Behind them the wave was about to crest, and below them, on a level fashioned into a smaller wave, stood four larger figures marching in a V-formation behind a man in the centre. On the left were two women, one a peasant and the other a sturdy housewife; on the right were two men, a worker and an engineer. The man and woman near the apex of the V together raised a laurel over the head of the man at the front. He stood on the lowest platform, but was larger than them all. A cape was draped cavalierly over his left shoulder, and his strong right arm was outstretched, pointing landward, as though he were emerging from the surf to redeem Alexandretta.

The heroic figure was Atatürk himself at the scene of his final triumph. His confident gaze was fixed on the last province he reclaimed from the Allies, the final piece of Turkey reassembled from the débâcle of the First World War, which saw the loss of an empire and the birth of a modern state. Like Moses, Atatürk had led his people through the water to the Promised Land, without reaching it himself. Less than a year before the French “Armée du Levant” withdrew on his terms, the “Father of the Turks” had died.

Near the Atatürk monument was a small outdoor café. I stopped there to drink a coffee. A waiter said something to me in Turkish, and I asked whether he spoke Arabic. He did. When he brought me a demi-tasse of Turkish coffee without sugar, he sat down and told me how difficult his life was. He said he worked long hours for little money. He had six children. “If I do not work,” he complained, “there is no bread.” Then he shrugged. “I’m an Arab,” he said, as if this were sufficient to explain his impoverished condition. To him and his compatriots, the Atatürk monument symbolised their defeat, the loss of their place in the Arab world and the severing of ties to their brothers in Syria. It mattered little that they, and not their “liberated” and divided Syrian cousins to the south, were living as all Syrians had lived for four centuries – under Turkish rule.

The beachless seafront was built over a large landfill, a few hundred yards of Turkey taken from the sea. On the wide pavement, it was the time of the afternoon promenade. Men pedalled past on bicycles with their wives on the back. Some had children perched in front. One man swept slowly along with one child on his handlebars and, on the back, a woman holding another child. All along the comiche, families were strolling, stopping to buy peanuts or hot, fresh popcorn from the many street vendors. The young boys’ heads were shaved to stubble. Women walked by in groups, none veiled, though many from the countryside wore brightly coloured scarves.

Turkish sailors, their European navy-style caps emblazoned TCB, joined the march, stealing furtive glances at the girls. Everywhere the sailors meandered, well-armed Military Police followed like vigilant dueñas. The MPs, smartly dressed from their white helmets down to the white spats over their black shoes, wore short truncheons on their hips and carried Belgian FN light automatic rifles. I saw no signs of trouble, and I suspected that, while the MPs were on duty, I wasn’t likely to. A few of the sailors were accompanied by their mothers and fathers, who had come to port to visit them.

I joined the parade of humanity on the seafront – Arab and Turkish townspeople, Alawis from the villages, Kurds from the mountains, Christians and Muslims. Mingling among the crowd, hardly noticeable until they approached you, were young boys and old men trying to make money on the pavements. They stood, dressed in old or badly fitting clothes, pleading with passers-by to give them money. Some merely begged, hands outstretched, with nothing to offer in return other than a blessing. Others shined shoes. Some sat in front of old scales, next to bits of cardboard with a few coins on top, and asked people to weigh themselves in exchange for a small donation. Most of the crowd ignored them, content to enjoy the evening promenade. Everywhere, in cafés and outdoors, in small groups and large, men sat at small tables and played cards or backgammon, all the while drinking tea or coffee, oblivious to the procession passing them by.

The sun was slow to set. The sea, where it met the breakwater, was quiet and unmoving. Nothing had disturbed Alexandretta for fifty years, an unpredicted moment of dull tranquillity in a bloody history of more than two millennia. The Bay of Alexandretta lay at the undefined point where the Aegean gave way to the Mediterranean. It was the northern frontier of the Levant – the 440 miles of coast between here and Al Arish in Gaza. Every port on this eastern Mediterranean shore, and every inland city each port served, had been invaded, besieged and destroyed dozens of times before and after Alexander the Great briefly united them in his empire. How long would this historic moment last? And when would the rest of the Levantine coast to the south, troubled by war and insurrection, enjoy again a generation of evenings like this one in Alexandretta?