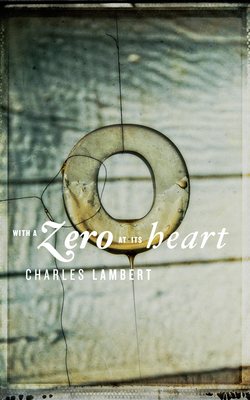

Читать книгу With a Zero at its Heart - Charles Lambert, Charles Lambert - Страница 10

Оглавление

1

They cycle out to a place about five miles from the village where the lane, little more than the width of a car, curves round to the right. At the side is the steeply sloping grass verge and, at the top of the verge, a metal fence. He hooks his bare legs round the lowest rung of the fence and lets himself down until he is dangling with his forehead no more than a foot from the soft summer tarmac of the road. The others sit along the top rail of the fence, waiting. Straining up, he can see the soles of their sandals. When the first car hurtles past him the rush of air is like an adult’s slap.

2

They stand around the pool in their winter clothes, scarves tucked into their woollens, their feet in wellingtons. The first child walks out onto the ice, and then the second. The pool, or pit as it’s known, is in a hollow, bare trees all round it. No one can see them, no one can hear them call. He joins the other two. Together they edge their way towards the centre of the pit. Beneath their feet, the ice is cloudy, irregular, less white than he’s expected, stripped branches trapped within it. He sees what looks like a harp, a doll, an uncle’s face, a deepness. With a rustle like fire, the crack comes running across the ice to greet them.

3

He is cycling home from school along the narrow lane when a car overtakes too close. He swerves into the verge. Some long dried grasses catch in the wheel and tangle among the spokes. Continuing to pedal, he bends down over the handlebars to disentangle them, tugging as the front wheel wobbles from side to side. The grasses hold. He reaches further in, as close to the spinning wheel as he can get. Before he knows it his hand is caught between spokes and fork and acts as a brake. He is thrown like a doll across and down and in front of his own bicycle, which tears at his back as his forehead skids along the road. Blood, blind.

4

She closes both eyes as soon as the bicycle begins to move at speed. She freewheels down the hill, the road the narrowest ribbon beneath her feet, a great rush and a darkness, a counting as far as she dares before she opens them. She is shaking with the wonder of her courage and the risk of it. Forty years later her son sits in a car at night, the lights turned off, and he is driven along a fen road, straight as a die, his eyes half-open, half-closed, by a woman whose eyes are entirely closed, and they are both laughing as hard as they can until she pulls up at the kerb and is sick into her lap.