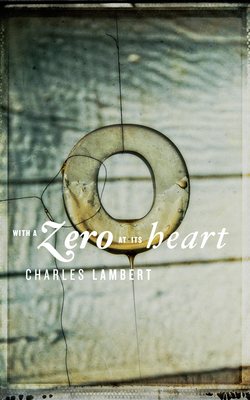

Читать книгу With a Zero at its Heart - Charles Lambert, Charles Lambert - Страница 7

Оглавление

1

He sits in the middle of the living-room carpet, piling up wooden blocks that have letters pasted on their sides while his mother watches Emergency Ward Ten on the black-and-white set. He’s spelling out his name when one of the nurses says something about sex rearing its ugly head. He doesn’t know what this means but he can tell from the odd way his mother shifts in her armchair and glances down at him that it’s something bad. He waits for a moment, and then asks her why sex has an ugly head and what rearing means. She tells him he’s too young to understand. When he spells the word SEKS with his blocks she takes them away from him.

2

Visiting his aunt’s house, he plays with the daughter of the family two houses down. She drags him out of the house and into the outdoor lavatory, then lifts up her skirt and pulls down her knickers. They’re supposed to be where someone can see them, he says, but she reaches for his shorts and quickly, as though she’s done this before, unzips them and pushes them round his knees, then makes him sit on the lavatory. She squats on his lap, her shoulders against his jumper, and wriggles. He can’t see over her head. His face is pressed into the cotton of her dress as she leans back into him. Do you like it? she says. No, he says.

3

They’re in the greenhouse. It’s tomato season and they’re surrounded by tomatoes when his best friend suggests they play nudist camps. They take their clothes off and then stand there not sure what to do next. They don’t touch. It’s hot and the smell of the tomatoes is almost overpoweringly strong. After a while, she suggests they play charades. He watches her growl, her chest as flat as his, then mount the handle of a spade the gardener has left in the corner and run with it pressed between her thighs. She puts the spade down and mimes the opening of a door. I’m a book, she says, but he can’t guess which one. He feels faint. Everything looks red.

4

Some weeks later they’re in her playroom, at the top of the house. This time they both take off their clothes and get into bed. It’s a single bed, beneath the window. They lie there, shivery at first and then hot. She pushes his head down under the sheets until his mouth is on her tummy, then further down. There’s a sprinkling of hair he doesn’t expect, which tickles him and makes him want to laugh, but he’s scared as well. Kiss me, she says, and he does. Harder, she says, but he doesn’t know what she means. He struggles back up until he can see his watch. It’s time for Five O’Clock Club, he says. I have to go.

5

They stand in the tent his father bought for him, a tall square tent like the kind you see in films about knights in armour. They all have their jeans around their ankles. The tent is made of some orange material. One of them has a handful of pigeon feathers. The boys push the hard end of the feathers into the ends of their dicks until they stick. The girls put the hard ends into their slits. They wriggle their hips to make the feathers move from side to side. He’s told them it’s what Red Indians do, to show they belong to the tribe. Their skins are bathed in orange. They’re sweating. One of the girls starts to cry.

6

It’s a sleepover with one of his friends from school. They’ve been put in the same bed, a double bed, with a bolster and a quilted eiderdown. They start off in their pyjamas, but his friend waits until the house is quiet, then asks him if he’s still asleep. No, he says. Neither am I, says his friend. They lie together, listening to each other breathe. It’s hot, his friend says, and takes off his pyjama jacket. He sits up to do it, his slim bare chest turned silver by the moonlight. That’s better, he says. He gets out of bed and slips his pyjama trousers off, then gets back in. Aren’t you hot? he says. His hand is hard.

7

It’s the afternoon of the boat race. His father wants them to watch it together, but he goes upstairs and lies on his bed. After a while, he opens his fly and reaches in, stroking himself until he’s hard. He carries on stroking and something strange happens, like soft white feathers pushing to come out. For a moment, he thinks he’s about to pee, to burst with pee, and will flood the bed, but then he’s moaning and he has some white stuff on his belly. He’s so excited he runs downstairs. He wants to tell his mother, but his father catches him in the hall, and he has time to reconsider. You missed a grand race, his father says.

8

He’s in the common room, between classes. One of the boys is being picked on by a group of other boys for being cocky. He keeps his head down, he doesn’t want to get involved. He’s had his eye on the boy for some time. Short blondish hair, solidly built. He’s never spoken to him, but he has had a dream in which the boy’s dick looks like honey and a piece of polished wood all at once, and he is stroking it. When they wrestle him to the ground, his shirt comes out of the waistband and his torso arches back, bare-bellied, taut. The whole world and his heart are blinded by the light of the boy’s white skin.

9

He buys Health & Efficiency from a newsagent’s where he isn’t known. He cuts out his favourite images of men and sticks them into last year’s Stoke Arts Festival programme, alongside the underwear pages from out-of-date catalogues, a photograph of Kevin Keegan, shirtless, running across an empty field, a smaller photograph, scissored from the paper, of the dark one from Starsky & Hutch dressed up as Houdini, wearing chains around his neck and wrists, and not much else. He’s hiding a new copy of H&E in his satchel the day his mother tells him about a piece of pig’s liver in some friend’s fridge, so riddled with cancer it wrapped itself around the milk. For the protein, she adds darkly.

10

He’s sitting in the back of the car, reading Brideshead Revisited when he hears the thwack of a leather ball against a bat. He glances up. His father is driving through a village and he sees a game of cricket being played. He hates cricket, but he has a vision of waiting beneath a tree, a willow tree perhaps, with a hamper of sandwiches and champagne, and his friend is walking towards him, his bat beneath his arm, his cheeks flushed. He flops onto the picnic rug and his hair falls into his eyes as he reaches across, his hand barely brushing the knee of his friend, his lips slightly parted, his words the merest whisper. And so they come.