Читать книгу One Hit Wonder - Charlie Carillo - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеI slept late, almost late enough to be charged for another day. It was Sunday afternoon, just past two P.M. I got dressed, packed up, and went to the front desk to check out. The pathetic rubble of a complimentary breakfast was available if I wanted it, coffee in Styrofoam cups and one solitary Entenmann’s doughnut, alone in a pile of crumbs.

I took a cup of black coffee, got some change from the desk clerk and went to the pay phone. The coffee was like battery acid but it packed the kick I needed. Two swallows and I was wide awake, ready to do what I had to do. The phone number hadn’t changed since my childhood.

“Hello?”

“Mom, it’s Mickey.”

“Oh my God, you sound so close!”

I swallowed. “I’m in New York, Mom.”

“Oh, my God! My God!!”

“Mom—”

“Are you all right? What happened? What’s wrong?”

“Why do you ask if something’s wrong?”

“You just show up out of the blue, and I’m not supposed to wonder?”

“Listen, Mom, I’m coming home for a while, okay? Would that be all right?”

She made a weird sound, the marriage of a cry and a laugh. “You don’t need permission to come home!”

“Well…thanks.”

“Where are you?”

“The airport.”

“Which one? Want your father to pick you up?”

“I’ll take a cab.”

“They’re so expensive!”

“I’m on my way, Mom.”

She had more to say but I hung up the phone, half sorry that I’d called. Now there was no turning back. My mother was waiting for me.

I hailed a yellow cab and of course the Muslim driver wasn’t delighted to be taking me to an address on the edge of Queens, knowing he probably wouldn’t get a return fare. As we got rolling I thought he was muttering about it to himself, but then I saw that he had a small cell phone clamped onto his ear and was chattering away to someone in his native language. I asked him to please hang up until the end of the ride. He nodded and did as he was asked but his eyes flashed with anger. Maybe he was a terrorist, talking about plans for another attack on the city, and I’d interrupted him. Maybe I was a hero.

I tipped him four bucks, and as he roared away I stood in front of my childhood home and stared in wonder at the little green asbestos-shingled house on Glenwood Street.

I had not been home in twenty years.

In the early days of my career I stayed at places like the Plaza Hotel whenever I came to New York (and sometimes wangled a room for my parents).

But I’d avoided the old neighborhood until now, until I had no choice.

The house seemed to have shrunk. Be it ever so humble, it was fully paid for, thanks to me. When the “Sweet Days” money rolled in I paid off the balance on my old man’s mortgage, $22,000. That was probably the only smart thing I did with my money.

So I had a right to be here, if only for that. My knees trembled as I approached the front door, climbed the three cement steps to the stoop and froze.

I didn’t know whether to walk right in, or knock on the door. How ridiculous was this? How many thousands of times had I barged in after school, dropped my books on the kitchen table, and headed straight for the chocolate milk in the refrigerator?

But that was a long, long time ago. Things had changed. Everything had changed.

Like a timid salesman I tapped on the door, almost inaudibly, but my mother heard it, all right. The door swung open and there she was, looking up at me as if I were a star in the night sky she was trying to recognize.

I’d forgotten about how short she was, barely five feet when I was in my teens, maybe four-eleven now with the shrinkage of time. But her wide-set eyes were still as I remembered them, radiant beneath a wide brow. Her short hair had gone salt and peppery but she still combed it straight back, like a duchess of discipline in a British boarding school.

“Michael,” she said, and then her arms were around me, briefly but tightly, as if she’d just pulled me in off the ledge of a skyscraper. She’s never once called me “Mickey,” hating it when the promoters decided my nickname would sell more records than my proper name.

Her hair was rich with the smell of the meat loaf she’d been cooking, and when she let me go she said, “Is that it?”

She was referring to my luggage. I nodded, setting down my green duffel bag.

“Yeah, this is it.”

“You’re shipping the rest of it?”

“Mom, there is no rest of it. This is it.”

Her nostrils widened with an insuck of breath, just as they used to when I was a child showing her a math test with a failing grade. After all this time it was nice to know I hadn’t lost my gift for disappointing her, and who wouldn’t be disappointed by a son who had nothing but socks, skivvies and T-shirts to show for himself after thirty-eight trips around the sun?

“Well,” she said, “come in, come in. Dinner is ready.”

My mother called the Sunday afternoon meal “dinner,” even though she always served it at four in the afternoon.

I realized I was still standing on the stoop. I took a deep breath, picked up my bag and stepped inside the house.

My father was standing by the tiny gas-jet fireplace they never used, hands hovering over the side pockets of his jeans, as if he were ready to reach for a pair of six-shooters.

“Hello, Dad.”

“Mick.”

We approached each other but stopped a few feet apart. He seemed shorter, too, and beefier, but he still had Popeye forearms. He’s an auto mechanic, and he’s always had these amazingly powerful forearms. He never missed a day of work, and that’s why he was known around Little Neck as Steady Eddie DeFalco.

His hair had gone totally gray but it was all there, and those brown eyes still burned out of his face with a weird kind of sorrow, the sorrow of a disappointed man who can’t even remember what it was he wanted and never got.

“I could have picked you up, you know.”

“The cab ride was fine.”

“Yeah, but they rob you.”

“Not so bad.”

“How much?”

“Twenty-eight.”

“Fucking crooks.”

“Eddie!”

He ignored my mother’s outcry.

“A twenty-minute ride, a dollar’s worth of gas. How do they hit you for twenty-eight bucks?”

“You got me, Dad.”

“That include the tip?”

“No.”

“Jeez, I hope you didn’t tip him more than three.”

“Four.”

“Big shot, eh?”

“Used to be.”

“Hug your son!” my mother commanded. “For heaven’s sake!”

An embarrassed grin crossed his face. He came to me as if to embrace me, but instead he grabbed me by the elbows of my dangling arms, squeezing tightly enough to make me tingle. It was a welcome home, a real welcome home.

“All right, come, let’s sit,” my mother said. “It’s on the table. Michael, you might want to wash your hands.”

I was home. Good God in heaven, I was home, and it really hit me hardest as I washed my hands in the downstairs bathroom, where a blue-green mineral drip stain on the porcelain sink had grown like an obscene tongue beneath the hot water spout.

I remembered when that sink was as white as snow. That’s how long I’d been away.

We ate at the kitchen table, the only place meals were ever eaten in this house. Nothing much had changed. There was a new coat of linoleum on the floor, and my mother had discovered refrigerator magnets, but the refrigerator they clung to was the same one I’d raided after school, and instead of my spelling tests there were coupons up on display. Back then the refrigerator was silent, but now it ran with an ominous hum, as if to warn that it could be just days, hours, minutes before it broke down once and for all….

“How was your flight?”

My mother was trying to jump-start a conversation. The three of us had been sitting there eating meat loaf and mashed potatoes, silent foods, mushy foods that made no noise when you chewed them. The silent food made the other silence all the more excruciating.

I swallowed the meat loaf, tangy with paprika. “It was all right.”

“Do you feel jet-lagged?”

“Mom. It’s three hours earlier in California.”

“Well, you know what I mean. Tired. Do you feel tired?”

If they knew I’d checked into a local motel for a night’s sleep they both would have had fits. Paying good money just to sleep! The waste!

“Nahh, I’m all right.”

I watched my father cut his meat loaf and bring his fork to his mouth. He has exquisite table manners, my old man. I never saw him gulp a drink or wolf a meal, and not until he’d chewed and swallowed did he speak.

“The pool thing didn’t work out, huh?”

In my sporadic communications with my parents about my working life I’d exaggerated what I’d been doing. I’d told them I’d been running a pool maintenance business that went bust. They had no idea I was just a hired bug-skimmer.

I shrugged. “I got run out of business by a big outfit. They undercut everybody’s prices.”

“Bastards!”

“Eddie!”

“Well, it’s rotten, that’s all. What’s the point? Why kill the little man?”

“It’s business, Eddie.”

“That’s not business, Donna. That’s murder, when you take away a man’s living.”

“Business is business.”

My old man let it go at that. He always let her get the last word, as long as his own words had been read into the record. I always admired him for that, even though I could never work that trick myself. I like getting the last word. I like getting the first word, too, and all the words in the middle. I’m like my mother that way.

She turned to me. “You want coffee, Michael?”

“No thanks, Mom.”

“It’s made.”

(Translation: I made it, don’t waste it, there are under-caffeinated children yawning away in Africa.)

“All right, I’ll have a cup.”

She cleared the plates away and set mugs of coffee, milked and sugared, in front of me and my father. That’s the way she did things. You got what you wanted all ready to eat or drink. Nobody ever asked anybody to pass the string beans or the mashed potatoes, because my mother loaded up the plates at the stove and carried them over.

It was like a diner. When I was sixteen I once left her a tip under my plate, and she didn’t think it was one bit funny.

While she did the dishes I sat back with the man who’d sired me and sipped coffee, coffee with absolutely no punch.

“Is this decaf, Mom?”

“Do you want regular? We don’t drink regular.”

“No, no, this is fine.”

“There’s a Starbucks now on Northern Boulevard,” my father said. “They line up for it. Latte. They need latte, these kids. Three bucks.”

My mother’s eyebrows rose. “How do you know how much it is?”

“I checked it out. Three bucks. More than that, if you want a grande.”

“You had a latte?”

“No, I didn’t have a latte. Calm down. I said I checked it out, that’s all.”

“A whole can of Maxwell House is two eighty-nine,” my mother said from the sink, where she had begun to wash the dishes.

My father nodded, turned to me. “Hear that?”

“I sure did.”

“A can costs less than a cup. Crazy.”

Having exhausted the coffee topic, we sat and looked at each other. Something was different about my father, really different, and at last it hit me. This was the longest I’d ever seen him without a cigarette in his mouth.

“You quit smoking, Dad?”

He laughed out loud, not in a happy way. Then he lifted a pack of Camels from his shirt pocket, just long enough for me to get a peek at it before shoving it back.

“I quit smoking indoors. Your mother doesn’t allow it in the house anymore.”

“Why should I breathe your smoke?”

“No reason I can think of.”

She turned to me. “It’s good for him. He smokes a lot less this way.”

“Yeah. Nineteen a day instead of twenty. That oughta keep the tumors away.”

He stood, shook a butt into his mouth, and turned to go outside.

“Welcome home, Mick,” he said before leaving.

Home. It’s supposed to be a comforting word, isn’t it? Everybody wants to go home. Home is where they can’t get you. Home is safety.

So why did the very sound of the word make me knock over my coffee?

In a flash my mother was there, mopping up the mess as if she’d expected it to happen. She was so quick on the scene that not a drop of coffee made it off the table to the floor.

“I’m sorry, Mom.”

“It’s all right, you’re jet-lagged.”

“I’m not jet-lagged.”

She tossed the wad of paper towels into the trash and reached for my empty mug. “I’ll give you a refill.”

“No, no. I think I’ll just take my stuff upstairs.”

“Your room’s made up!” my mother called after me as I climbed the stairs.

The air in my room was tart with the smell of Lemon Pledge. My mother had obviously run up here and given it the once-over right after I called from the airport.

Here was my bed, narrow as a monk’s, with the same pebbly-patterned red bedspread that left an imprint on your cheek if you fell asleep with your face against it. My Hardy Boys books were still lined up in a row on the windowsill, and beyond them was the little desk where I’d done my homework by the light of a black twist-neck lamp…still there, of course. There were clean towels at the foot of my bed, hotel-ready for my needs.

I closed the door to my room and wished it had a lock. Then I made sure they were both downstairs before opening my duffel bag.

Nestled among my clothes was an old coffee can with a taped-on lid. I peeled off the tape and dumped the contents of the can on my bedspread.

It was piles and piles of cash, neatly rolled up and rubber-banded, an absolutely obscene sight. I didn’t even know how much it was.

Hoping and praying that my parents would stay downstairs, I took off the rubber bands and counted the money. The grand total came to $5,740.

This was funny money. I hadn’t exactly stolen it, but at the same time, it wasn’t exactly mine. I was going to have to think long and hard before I decided what to do with it.

I realized how stupid I was. My duffel bag had gone through the X-ray machine at LAX. What if the security guards had been alarmed by the bomb-like outline of the can? I was lucky I’d gotten through. I was also lucky that nobody had robbed me at that shitty airport hotel where I’d spent the night.

But then, people have always said I was a lucky guy.

Now I faced the biggest hurdle of all—figuring out a place to stash the cash.

I didn’t know what my mother’s housecleaning habits were like these days but she used to fine-tooth the place once or twice a week, and how was I going to explain a coffee-can fortune? She’d think her only begotten son had become a drug dealer, and who could blame her, the way I’d landed on them out of the blue in need of a roof, a shave, and a soul, not necessarily in that order?

And then I remembered something, and I knew what I had to do.

I stuffed the cash back into the coffee can, taped the lid in place, and dragged the desk chair to my closet.

Way up inside the closet, higher than its highest shelf, was a kind of a hole in the wall, a deep gap in the bricks where I used to hide Playboy magazines. I had to climb up on a chair and stand on tiptoe to reach it, which meant it was completely out of my mother’s radar range.

I got up on tiptoe, set the can into the hole, and told myself she’d never find it. Then I unpacked my duffel bag, putting my clothes neatly in the bureau drawers.

And then a funny thing happened. I was suddenly completely exhausted, as if I hadn’t slept in weeks.

It was a warm night. I opened the window, stripped down to my skivvies and got into bed. Then I noticed something I hadn’t noticed earlier, hanging on the wall over the foot of my bed.

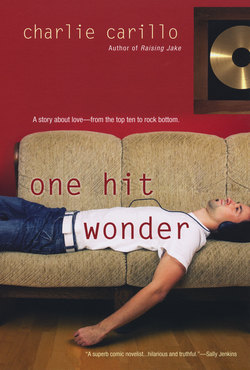

It was the jacket from my one and only hit record, hung in a gold frame, as if it were some kind of religious icon. My hair had been barbered into a sort of punkish buzz cut, with slanted sideburns and a glaze of gel. My head seemed almost to be ablaze, as the photo was taken with the sun setting behind me. I stood on a beach with my arms folded across my chest, the top two buttons of a snug black silk shirt undone (“Let the chest hair peek out!” the photographer had shouted).

I stared at myself on that wall, twenty years younger and twenty pounds lighter. Young Me stared back just as hard, grinning as if God had just whispered in his ear that the rest of his life was going to be a toboggan ride down Whipped Cream Mountain.

“The fuck you lookin’ at?” I asked the record jacket, but I got no answer.

I was just about asleep when a coughing sound jolted me. I got up, went to the window and looked out at the backyard, where my father was lighting up a fresh cigarette. He shifted his weight from foot to foot, like a man waiting for a bus that was never coming.

I got back in bed and shut my eyes. I could smell cigarette smoke and hear the clatter of pots being scrubbed by my mother down in the kitchen.

Smoke and clatter. I was home, all right.