Читать книгу The Midwestern Native Garden - Charlotte Adelman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

For as long as I can remember, I have loved wildflowers. Having a wonderfully large backyard enabled my husband and me to create large, colorful beds of flowers. Many happy evenings were spent devouring catalogs as ambitious color-coordinated schemes danced in my head. I ordered, and we planted, daffodils, tulips, daylilies, peonies, hostas, and ‘Autumn Joy’ sedum. And because these “old favorites” decorated the yards of most of our neighbors and constituted the inventory of most local and national nurseries, we assumed these were the right ornamentals to plant. Because we love birds, we lined our borders with berry- and fruit-producing trees and shrubs. Later, to our horror, we discovered that most of our well-meaning plant choices were not native to North America and that some were invasive pests. We realized we had made choices without first getting good information.

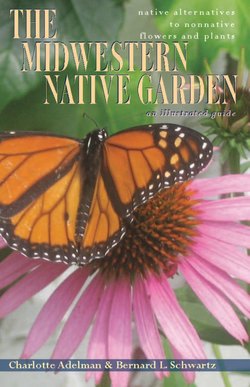

While I was walking with my dog one afternoon, I spied a brilliant yellow goldfinch extracting a seed from the iridescent center of a purple coneflower. Belatedly, it dawned on me that flower seeds, not only the fruits, provide birds with food. During another walk in a local park, I noticed that the hostas and daylilies from China did not attract much of anything. In contrast, and to my astonishment, numerous butterflies, skippers, and bees surrounded the native blackeyed Susans, coneflowers, and blazing stars. This produced another epiphany: I could transform my garden of colorful nonnative flowers into a garden of colorful native flowers that welcomes butterflies, other beneficial and beautiful insects, and birds. From these experiences, my gardening ideas evolved. Before long, the backyard lawn was removed, the nonnative ornamentals were put on the compost heap, and a local prairie expert was hired to help me create a backyard urban prairie/savanna.

These days, I stroll on a woodchip path through a fragrant, colorful kaleidoscope of native sedges, grasses, and flowers right in my own backyard or observe the everchanging scene from a strategically placed bench. I watch goldfinches sip rainwater from little cups formed where cup plant stems meet the leaves. I observe songbirds visiting my yard’s seasonal offering of seeds and fruits. The butterflies, skippers, and bees that ignored my introduced ornamentals now visit my native flowers and grasses for nectar, pollen, and reproduction habitat. Monarch butterfly visits to my oh-so-fragrant common milkweeds actually result in monarch butterfly caterpillars! Tiny oligolege, or specialist, pollinator bees spend sunny hours at my beautiful blue American bellflowers. I remember exclaiming in surprised delight upon seeing a hummingbird hovering at an orange flower on the honeysuckle vine I had planted specifically to attract hummingbirds. Many happy evenings are spent devouring native plant nursery catalogs, as images of native wildflowers dance in my head. The absorbing new world we created just outside our door inspired us to explore the fascinating world of the midwestern prairie, and one result of this was a collaboration between my husband and me on the book Prairie Directory of North America.

Recognition of the problems associated with invasive nonnative plants led me, in consultation with and encouraged by William E. McClain, now-retired Illinois Department of Natural Resources (DNR) naturalist and author, to draft a proposed amendment to the Illinois Exotic Weed Act (525 ILCS 10). Though the effort failed, the experience was illuminating. I presented the local Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) with petitions, signed by hundreds of people, asking the department to stop mowing roadsides planted with native grasses and flowers, and achieved some success. When nonnative purple loosestrife invaded the marshy lake where we have a house, we worked with the Wisconsin DNR to eradicate the “purple plague.” Invasive nonnative garlic mustard degrading a local park inspired me to secure park district permission to create an annual garlic mustard pull. The sight of children playing on pesticide-treated lawns in the village where I live led me to successfully campaign for pesticide-free, village-owned lawns. The village’s publication of a list of proposed plantings for a local development that included invasive nonnative plants prompted me to provide a list of suitable native alternatives, which the trustees adopted. When local mothers creating a middle school prairie garden asked for suggestions on native spring flowers to replace the usual nonnative ones, I shared a similar list with them. Creating a one-acre wetland prairie in my village park district’s retention basin is my most recent project.

We are not instinctively aware of the benefits of gardening with native plants. But reading, joining informative groups, and close observation can teach us that native plants provide native birds and butterflies with vital food and reproductive sites not available from nonnative species. We can discover that choosing native plants helps prevent their extinction. We are not born with the knowledge that nonnative invasive plants damage the environment. It is up to us to learn how many nonnative plants that began life in North America as popular ornamentals became today’s most invasive plants.

We wrote this book to make information and insight that we acquired over time immediately accessible to others. I have derived much joy from observing local birds, bees, and butterflies interacting with midwestern native flowers and plants and from the beauty, fragrance, and reliability of these plants. Learning the importance of native flora and fauna to a healthy ecosystem inspired me to act, and that in turn has given me much satisfaction. Whether we proceed in small incremental steps or with big landscaping projects, each of us can decide to choose native plants as alternatives for nonnative ornamentals. We hope the information that we share will intrigue and inspire you, too.

CHARLOTTE ADELMAN