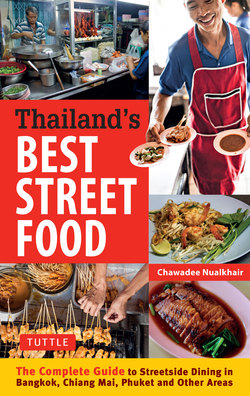

Читать книгу Thailand's Best Street Food - Chawadee Nualkhair - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Is Street Food Dying Out?

A few months ago, a friend said to me that Thai street food would most likely be around for only another “10 to 15 years”. This statement surprised me but I really couldn’t argue with him. International food chains have mushroomed in most of Bangkok’s urban centers offering cheap and affordable foreign specialties such as hamburgers and Japanese curry rice, and Thais aren’t resisting them. In fact, Thais—to use the slogan of one popular fast food franchise—“are loving it”. A study published in the Journal of Health Science in early 2012 indicated that Western fast food is one of the top ten snacks most commonly eaten by Thai children. The reasons for this are many, but they all boil down to the fact that international fast food has become more readily available and costs only slightly more than Thai food on offer at the average food stall down the street.

I am not really bemoaning the globalizaton of Thai diets. It’s true that, for many people, street food and fast food are interlinked—nourishment meant to be grabbed quickly on the way somewhere, when one is too hungry to wait for something better. After all, street food blossomed in just this way. It was initially sold as quick noodle snacks for those on the go by enterprising Thai-Chinese vendors along Bangkok’s many canals, and then became popular for harried parents who needed to buy quick dinners on their way home from work.

Street food in Thailand has grown into a fairly substantial business, possibly grossing as much as 800 billion baht a year, according to very rough estimates from JP Morgan. However, Thai street food—like much of Thai culture in general—has shown an amazing ability to adapt and absorb influences which would threaten to engulf lesser entities. I like to compare it to “High Street” fashion, the lower-priced styles that the average person wears. Many times, the High Street is influenced by haute couture just as Thai street food has been influenced by more expensive restaurants. For example, the coconut milk-based curries of the common khao gub gaeng (rice with curry) stall did, after all, originate in far grander kitchens.

Thai street food has moved well beyond noodles and curries to encompass an extensive range of snacks, salads, soups, sweets and heartier wok-fried noodle- and rice-based dishes. All incorporate a diverse array of ingredients, from regional favorites such as the Northern Thai sour fermented sausage known as naem to newfangled concoction like instant noodles. Some have even taken their cue from foreign cuisines, presenting takoyaki (fried octopus balls), a mutant Thai take on sushi, or standard Western favorites like beef stroganoff, for a third of the price. And, yes, sometimes High Street does inspire haute couture if the recent spate of upscale restaurants featuring Isaan food, once derided as a “low-class” street staple, is anything to go by. It is difficult to ascertain a more precise figure as many of the stalls are unregulated and thus form part of the shadow economy.

So what do I think about my friend’s prediction? In Thailand, there will always be a market for well-made cheap food in an informal setting without bells and whistles, such as air-conditioning, proper chairs or even tables. Thais have long shown that they are willing to withstand any sort of inconvenience in the pursuit of something culinary, provided it is worth it. I believe that fifteen years from now, Thai street food may look different and may comprise different dishes but it will definitely still be delicious and will remain uniquely Thai.

HEALTH CONCERNS

In today’s world, no kind of dining is without its risks. Street food obviously carries with it its own set of issues, so buyer beware. For this reason, I have tried as best as I can to stick to long-standing street food vendors with good reputations. Focus on well-established places with high turnover and try to avoid raw seafood or meat. Vendors are periodically tested by city authorities for cleanliness. The ones that pass muster are marked by a green and blue “Clean Food Good Taste” badge issued by the Bangkok administration.

Types of Thai Street Food

There is, and always has been, a great deal of debate on what street food is. For some, it must be something sold directly from a cart or table set out on the sidewalk; for others, it is nothing more than food sold from any open-air place (or, as the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration puts it, an establishment with “no more than three walls”).

My view on this matter falls somewhere in the middle. Many open-air Thai eateries are nothing less than full-fledged restaurants serving a wide range of dishes from an extensive menu, while other shophouses specialize in a specific dish or niche of Thai food.

1 Mobile

The standard idea of a typical street food vendor is mobility. These vendors usually operate from a single mobile cart that specializes in takeaway or a cart with tables set up around it. Occasionally, the vendor sells his or her wares from a pole with baskets fixed to either end or from a table placed on the sidewalk. The vendor may sell from either a fixed location or move around from time to time. They normally specialize in one dish or in one type of food, such as Isaan, or Northeastern Thai food.

2 Made-to-order These aharn tham sung vendors operate from fixed locations, usually out of a shophouse. They make a variety of dishes but generally rely on a fixed repertoire of specialties. Some of the very best (these are usually characterized by the baskets of fresh ingredients on display in front of their woks) make whatever you request or are able to make up dishes depending on what ingredients you select.

3 Shophouse Vendors selling food from a shop-house are usually the most successful and oldest in their trade. Many vendors start from carts and eventually work their way up to a shophouse that is able to accommodate more guests and provide the vendor with better cooking space. They generally stick to their original specialties but from time to time branch out into other dishes that are related in some way to the specialty that made them famous. The most successful vendors move on from shophouses to adjacent air-conditioned rooms and, eventually, open up full-fledged restaurants.

4 Curry rice The khao gub gaeng (also khao raad gaeng) vendor’s cart or table has a selection of ready-made curries and stir-fries displayed in front of the vendor. Curries and stir-fries may change from day to day but the vendor usually has a specialty that never changes. Customers simply point to what they want and it is either served on a plate of rice or placed in a clear plastic bag for taking home.

How to Use This Book

Street food is a serious matter to a lot of people. Many normally laid-back and happy-go-lucky people can get pretty hot under the collar when the conversation takes a culinary turn. Debates over the best places to grab a bowl of noodles or even what does or does not constitute a street food stall can easily devolve into impassioned free-for-alls. To make things easy (for myself) and to reduce the number of irate emails about this or that street food vendor, I would like to set out my criteria for what constitutes a street food stall, how I make the selections for this book, and the purpose I hope the book serves.

The Purpose of This Book

This book started from the feeling of intimidation I had when I moved to Thailand nearly 20 years ago and contemplated buying a street food meal on my own. Not knowing the language as well as I should, I was unsure about what to order, what I’d actually be getting and how to ensure I got what I wanted with as little fuss as possible.

This guide seeks to address those issues while focusing on long-standing and relatively hygienic vendors who enjoy a high turnover. In other words, the stalls I have selected are almost all famous in one way or another. There may well be a great fried noodle stall tucked away somewhere in a corner of Chinatown that has better food, but if it is obscure or relatively new, it could easily move to another location or simply cease operating altogether, hence my focus on the older, more established street food purveyors. I also find the better known stalls are the most patronized ones, and I like the idea of a quick turnover of ingredients. This cuts down on the chance of items being left to “stew” in the open for hours, if not days.

Ultimately, this book is meant to help street food newbies who are unsure about street food but who still want to share in something that is undoubtedly a huge part of Thai dining culture. There is no need to stick to big restaurants or to cower in one’s hotel coffee shop. On the other end of the spectrum, long-time street food aficionados may also come across something in these pages for them: a reminder of a long-forgotten favorite or a vendor or two who serves a beloved dish in an unfamiliar town. I hope they, too, will find this book useful.

What is a Street Food Stall?

The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration recognizes two types of vendors: mobile vendors who sell from carts or carry their wares slung on a pole across their backs, and fixed vendors who sell from a stall, usually extending from a house or in a shophouse. These fixed locations are defined as places with no more than three permanent walls. I am being unusually detailed about this because most of the stalls in this book are of the shophouse variety. I have also added other criteria which I hope will separate these vendors from open-air restaurants that also operate out of shophouses:

1 There must be one or, at most, two specialties “of the house”

2 The kitchen must be located in front of the dining area, in full view of the diners

I like the more flexible approach to characterizing street food stalls because many vendors, after having spent years building up a reputation from their mobile carts, have moved to fixed locations and may have opened either full-fledged restaurants (see Polo Fried Chicken, p. 71) or other branches (see Bamee Sawang, p. 57). That is the story of street food. The good ones flourish and sometimes expand. Others have to move to a location that may serve them better. The good thing about Thailand is that there is always a place somewhere for an enterprising food vendor. You may find that places that are clearly street food stalls are not included. This is because they are either aharn tham sung (made-to-order) stalls or khao gub gaeng (curry rice) stalls which feature pre-made curries. There are simply too many of these to include.

Choosing the Stalls

I spent many months eating at the stalls featured in the book so the basic answer to the question of choice has to be “I like the food at these places.” But there are other criteria. In Bangkok, for instance, I focused on neighborhoods that I knew well, hence the exclusion of important areas like Victory Monument and Ari. I didn’t want to include stalls just for the sake of including them even if they were located in well-known neighborhoods.

In the provinces, I focused on regional specialties and dishes that are harder to find. I wanted to showcase the diversity inherent in Thai food as well as show off the different characteristics of each region. You may find that, as in Bangkok, your favorite neighborhood or city is not included. The reason is because I have but one humble stomach and have a limited amount of time on this good green earth. It is a work in progress. Maybe some day I will be able to provide a wider coverage.

The whole premise of this book is that no two vendors are created equal. Egg noodles aren’t the same wherever you go. The same applies to chicken rice or duck noodles or any other street food dish you may favor. This is why (with the exclusion of Sukhumvit Soi 38, which is special) I do not focus on well-known street food areas. The vendors are simply not all of the same standard. If the “neighborhood/night market/walking street approach” is your favorite way of exploring street food, then by all means go ahead. You will not need this book to do it. What I do hope is that this book ends up inspiring you to hit the pavement and explore, not just the places in the book but whatever it is that may strike your fancy—just eat it.

I want discussions, questions, heated exchanges. Readers of my first book have given me feedback, both good and bad, on all the Bangkok vendors. That feedback invariably makes me happy even though it is occasionally negative, because it means the book has, in some small way, contributed to each reader’s search to discover what they love and what works for them.

NOODLES IN SOUP

First brought to Thailand by Chinese immigrants, this “Chinese fast food” has morphed into a suprisingly wide variety of dishes based on:

1 Types of noodles

2 Main ingredients (proteins) with the noodles

3 Styles of broth

4 Whether you want your noodles with or without broth

Types of Noodles

Bamee บะหมี่

Chinese-style egg and wheat flour noodles

Giem ee เกี้ยมอี๋

A type of hand-rolled Chinese noodle resembling spaetzle

Giew เกี๊ยว

Wonton, usually filled with a type of pork stuffing

Guay jab กวยจั๊บ

A type of hand-rolled longer Chinese noodle always served in a pork broth

Sen lek เสนเล็ก

Thinner, flat noodles made from rice flour

Sen mee เสนหมี่

Rice vermicelli—tiny angel hair-like noodles made from rice flour

Sen yai เสนใหญ

Wide noodles made from rice flour

Sieng hai เซี่ยงไฮ

Green hand-rolled Chinese noodles

Wunsen วุนเสน

Glass vermicelli noodles made from mung beans

Main Ingredients

Guay jab กวยจั๊บ

Choice of clear or cloudy pork broth always accompanying hand-rolled Chinese noodles

Han หาน

Goose (served roasted)

Moo หมู

Pork (served as meatballs, barbecued, sliced or as mince)

Nam sai น้ําใส

Clear broth

Nam tok or leuat น้ําตก

Includes animal blood

Nuea เนื้อ

Beef (served stewed, freshly boiled or as meatballs)

Ped เป็ ด

Duck (served roasted)

Phae แพะ

Goat (served roasted or braised)

Styles of Broth

Pla ปลา

Fish (served freshly boiled or as meatballs)

Talay ทะเล

Mixed seafood (usually shrimp, squid and fish)

Tom yum ตมยํา

Like the soup, a spicy lemongrass-infused flavor

Taohu เตาหู

Tofu, usually deep-fried into a type of meatball

Yen ta fo เย็นตาโฟ

Red fermented tofu sauce accompanying seafood noodles

FRIED NOODLES

กวยเตี๋ยวผัด

Noodles are not only served in soup. They are also fried in a variety of styles. Most food stalls will specialize in one or two types of fried noodle. The dishes are usually eaten with a fork and spoon.

Khanom jeen

ขนมจีน

This fermented rice noodle is often mistaken for a Chinese dish because its name mistakenly translates into “Chinese candy”. It is, in fact, of Mon origin and is served alongside a variety of curries, the best known being nam prik (chili sauce), gaeng kiew waan (sweet green curry) and nam ya (fish curry). Khanom jeen is usually available at a khao gub gaeng (rice curry) stand.

Pad kee mow

ผัดขี้เมา

Known familiarly as “drunken noodles”, these noodles are fried with a variety of spices and are typically ordered after a big night out when the diner has indulged in a few too many drinks. Served with a protein (pork, chicken, seafood or beef), the dish is usually available at aharn tham sung (made-to-order) stalls.

Pad Thai

ผัดไทย

The best-known type of fried noodle dish, the noodles here include both Chinese and Thai elements, such as rice noodles, tamarind juice and shrimp. Diners can usually opt for pad Thai with or without egg. Pad Thai vendors usually also serve hoy tod, a type of oyster-topped omelet or eggy crepe.

Rad na/Pad see ew

ราดหนา/ผัดซีอิ๊ว

Served with pork, chicken, seafood or beef, these rice flour noodles are fried and then covered in a thick gravy. The same stalls that serve rad na usually serve pad see ew, or rice noodles fried with soy sauce and some form of protein (pork, chicken, seafood or beef).

RICE DISHES

อาหารประเภทขาว

Rice, or khao, forms the backbone of Thai cuisine so it’s no surprise that it features prominently in street food. The following are the best-known types of rice dishes available:

Jok โจก

This Chinese-style rice porridge features smaller rice kernels and a thicker consistency than the Thai variation. It is usually accompanied by slivered ginger, green onion, pork meatballs, liver and/or innards. A half-cooked egg is optional as is the accompanying patongo (deep-fried dough).

Khao ka moo ขาวขาหมู

Rice served with a fatty, braised pork leg accompanied by braised leafy greens and a sour, vinegary chili sauce to cut the fatty aftertaste.

Khao man gai ขาวมันไก

A Thai-Chinese dish, steamed chicken with fatty rice is served with a clear broth and at least one form of chili-spiked brown bean sauce.

Khao mok gai

ขาวหมกไก

Loosely translated as “chicken buried in a mountain of rice”, this Thai-Muslim chicken dish usually features a chicken leg accompanied by rice colored yellow by turmeric, topped with deep-fried shallots and a spicy-tart chicken broth.

Khao na ped/moo

ขาวหนาเป็ ด/หมู

Rice topped with barbecued duck or pork. Both are usually served at the same food stall.

Khao niew gai yang/gai tod

ข้าวเหนียวไก่ย่าง/ไก่ทอด

This Northeastern Thai dish comprises sticky rice accompanied by barbecued or fried chicken and, usually, som tum (green papaya salad). It is among the more popular street food options in Bangkok.

Khao pad

ขาวผัด

Fried rice, usually served as part of an aharn tham sung cart but occasionally offered by noodle vendors to placate customers who either want something extra or aren’t in the mood for noodles.

Khao tom

ขาวตม

This Thai rice porridge is either served plain with a number of small side dishes or with a variety of proteins included in the broth (usually fish, assorted seafood, pork or chicken).

APPETIZERS

AND SNACKS

อาหารวาง

Thais are often described as “inveterate snackers” and their fondness for grazing usually leads them to one of these types of snacks between meals:

Guaythiew lod

กวยเตี๋ยวหลอด

Another type of flat noodle, this one is stuffed with pork or seafood and drizzled with a delicious sauce. The best examples of this are found in Chinatown.

Hoy tod

หอยทอด

Oysters fried in omelet, served with a sweet red chili sauce. These vendors usually also serve pad Thai.

Khanom jeeb

ขนมจีบ

These steamed Chinese dumplings include pork and seafood. The best examples can be found throughout Chinatown.

Krapho pla

กระเพาะปลา

Fish maw soup. The best examples are again found in Chinatown.

Nuea khem

เนื้อเค็ม

Translated as “salty beef”, this form of beef jerky—traditionally dried in the sun—is usually eaten with sticky rice. It keeps well.

Samosa

ซาโมซา

The Indian deep-fried dumpling with a savory, tart stuffing. Also sometimes accompanied by tikki, a deep-fried soft patty with a spicy stuffing.

Satay

สะเตะ

Available as pork or chicken, the protein is grilled on a bamboo skewer and coated with coconut milk. It is accompanied by peanut sauce and a cucumber and shallot relish.

DESSERTS

ของหวาน

Thais are known to harbor a fondness for sweets so it’s no surprise that street food desserts abound.

Bamee wan

บะหมี่หวาน

Egg noodles served with an assortment of Thai-Chinese delicacies in syrup and topped with shaved ice.

Bua loy kai waan

บัวลอยไขหวาน

Translated as “floating lotus sweet egg”, these dumplings are served in heated coconut milk with an egg or egg white.

Bua loy nam khing

บัวลอยน้ําขิง

Translated as “floating lotus with ginger water”, this Chinese dessert comprises dumplings stuffed with ground sesame seeds served in a sweet, invigorating ginger syrup.

Chao guay

เฉาก วย

This Chinese jelly, served in a syrup with ice, is reminiscent of sweetened black coffee and is a light, refreshing treat at the end of a big meal.

Khanom bueang

ขนมเบื้อง

These interesting taco-like desserts mix elements of the sweet with the savory.

Khao niew mamuang

ขาวเหนียวมะมวง

Sticky rice with mango and coconut milk. One of Thailand’s best-loved desserts.

Lotchong

ลอดชอง

These green “tapioca squiggles” are served in an iced coconut milk broth.

Pae guay

แปะกวย

Yellow gingko nuts can be served alone, hot or cold, in a syrup or even part of a Thai-style shaved ice “buffet”. The Chinese have traditionally believed this dessert helps promote brain function.

Roti

โรตี

Like their Indian counterparts, these are flat breads but are flakier and served with a variety of sweet toppings, such as banana or condensed milk and sugar.

BEVERAGES

เครื่องดื่ม

You will typically find one or more of the following beverages at a street stall:

Cha dum yen ชาดําเย็น

Black iced tea

Cha manao ชามะนาว

Iced lemon tea

Cha yen ชาเย็น

Iced milk tea

Gafae yen กาแฟเย็น

Iced coffee

Geck huay yen เกกฮวยเย็น

Iced chrysanthemum tea

Lorhangguay หลอฮั้งกวย

Chinese herbal beverage

Nam atlom น้ําอัดลม

Soft drink/carbonated beverage

Nam bai bua bok น้ําใบบัวบก

Pennywort juice

Nam baitoey น้ําใบเตย

Pandanus leaf juice

Nam buai น้ําบวย

Pickled plum juice

Nam dok anchan น้ําดอกอัญชัญ

Butterfly pea juice

Nam farang น้ําฝรั่ง

Guava juice

Nam khaeng น้ําแข็ง

Ice

Nam krajiep น้ํากระเจียบ

Roselle juice (sometimes referred to as hibiscus juice)

Nam lamyai น้ําลําไย

Longan juice

Nam manao น้ํามะนาว

Lime juice

Nam maphrao น้ํามะพราว

Coconut juice

Nam matum น้ํามะตูม

Bael fruit juice

Nam plao น้ําเปลา

Fresh water/drinking water

Nam saowarot น้ําเสาวรส

Passionfruit juice

Nam som น้ําสม

Orange juice

Nam takrai น้ําตะไคร

Lemongrass juice

Olieng โอเลี้ยง

Chinese-style black iced coffee