Читать книгу The Upholstery Bible - Cherry Dobson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE UPHOLSTERER’S ART

Traditional methods of upholstery are still used today despite the invention of synthetic fibres. Upholstery is a skilled craft requiring judgement and dexterity and every piece of furniture needs to be approached differently. The stuffing is built up gradually following the contours of the frame and the upholsterer has to judge whether the shape and height look and feel right.

An ornate French armchair, from the reign of Louis XVI. With upholstered seat, back and arm rests. This is the work of a famous Paris-based master upholsterer called Georges Jacob (1739–1814).

Early upholstery was rudimentary. Girthweb – the type of webbing used for making saddle girths – was woven across the frame and tacked at the edges. In France it was close-woven, but elsewhere there were large gaps between the girths. The webbing was then covered with a piece of hessian or coarse sackcloth and some form of padding was piled on, either feathers, wool, animal hair or vegetable matter such as straw, chaff, rushes or dried grasses and leaves. Occasionally the padding was roughly secured with bridle ties before the top cover was nailed on. The backs of chairs were usually stuffed with washed and curled real hair, which was more expensive, stitched onto a linen or canvas backing. After about 1660 real hair was used to a much greater extent and the front and sometimes the sides of the seats, which received the greatest wear, were strengthened with an extra band of stuffing sewn into a roll of hessian or canvas. Additional layers of fabric, usually wadding or linen, were placed between the real hair and the top cover to prevent the hair from working its way through the fine fabric above. Some chairs had loose cushions filled with down or feathers.

In the eighteenth century these techniques were refined, and complicated curved and straight-edged upholstery was carefully moulded by more precise stuffing and stitching. Often there were two layers of stuffing on the seat – one thin layer of real hair above a thicker layer of cheap vegetable fibre. Sometimes the padding was held in place with stitching or with regularly spaced ties that gave the surface of the upholstery a slightly indented pattern. This is now called shallow buttoning or tufting because silk tufts and not buttons were used as a decorative finish to each tie. In France, tufting was described as capitonné. Buttons did not replace the ties until the end of the eighteenth century. Until the middle of the eighteenth century, the upholstery of a chair or sofa was its most important part and often cost more in materials and workmanship than the frame. Consequently the upholsterer, or “upholder”, was held in high esteem. In France the two crafts of tapissier (upholsterer) and menuisier (chair maker), were kept entirely separate.

The upholsterer often supplied all the textile furnishings of a house, from the elaborate wall hangings and curtains down to simple pillows and mattresses. As an interior designer, advising his clients on their choice and arrangement of furnishings, he probably had a greater influence on the final appearance of a house than the architect who designed it. (Most upholsterers were also undertakers and supplied the accessories that decorated the funeral cortège and the elaborate black curtains and ornaments that decorated a house during mourning.)

SEATS GET MORE COMFORTABLE

Deep buttoning resulted from the widespread use of the coiled spring after 1820, which greatly deepened the padding. This springing was the only major advance in upholstery technique for over a century. The addition of a layer of springs underneath the layers of stuffing allowed the upholstery to move slightly and therefore made it more comfortable. The backs as well as the seats were often sprung and the thicker stuffing needed to cover the springs was prevented from slipping by the deep-set buttons. The resulting pleating of the material became a decorative feature and buttoning sometimes appeared on the arms too, though they were not always themselves sprung.

At first, springs were attached at the bottom to wooden planks, i.e. similar to modern ready-made wood and metal sprung units, which simply slot into the frame. These were soon replaced by more flexible webbing.

Between 1650 and 1800, real hair was used for the padding, but as it became more expensive, other materials were used to pad it out. These have included coconut fibre, known as coir or kerly fibre, various coarse grasses and leaves, cotton, rags and wool waste, and even wood chippings. The 20th century saw the introduction of rubber webbing, staple guns, latex and polyurethane foam.

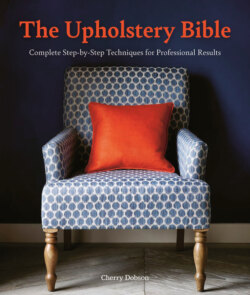

A modern armchair with foam padded seat and back.