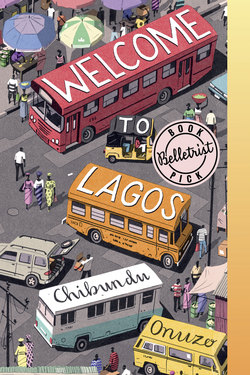

Читать книгу Welcome to Lagos - Chibundu Onuzo - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

ISOKEN DID NOT SPEAK until they reached Edepie Motor Park. It was a large trampled field with vehicles of all sizes coming and going, small, dusty minivans, large, sleek, luxurious buses, trailers with art twisting all over their bodies, movement and noise and dust rising from the spinning tires. A market had sprung up for the human traffic, clothes, books, food, toys on display for the discerning traveler.

“Please can I go to a call center,” Isoken said to Chike when they arrived. “Maybe I’ll remember my parents’ number with a phone in my hand.”

The owner of the kiosk stood by Isoken as she dialed wrong number after wrong number. With each try she grew more flustered.

“There are others waiting,” the kiosk owner said after her sixth attempt. She cried out when the phone was taken from her, a harsh, bleating sound.

“Don’t worry. I won’t charge you,” the owner said, beckoning to the next customer.

Chike would have preferred tears to Isoken’s twitchy silence. Her hand rose to her hair, then her collarbone, then her elbow as if she were counting her body parts, checking nothing was missing.

“So we’ll have to go to Lagos, then,” Chike said to her when her fingers were resting on her ear.

“My mum used to say that if we ever got separated we should meet at home. The first time it happened was when I was a child. I ran off in the market after an orange and when I caught it, she was gone. I clutched so many strangers that looked like her from behind and then I got tired of disappointment and decided to go home. She came home that night with dust in her hair. She was already planning how she would tell my father that she had lost their only child.”

“So you think they’ll be in Lagos.”

“I don’t know, but I can’t stay here.”

She stared away from him when she spoke. There was swelling on her cheekbone, the skin puffed and raised, encroaching on her eye. The cut on her temple had formed a deep purple scab, the shade of an onion. He had not asked for this new responsibility. He hoped there would be someone to help her in Lagos.

Yẹmi and Chike bought trousers from a stall and went behind a tree to change. They emerged civilians, their muddy boots the only sign of their former life. Their dinner was a simple meal of beans and stew, eaten on the same bench with Isoken as far from him and Yẹmi as possible.

They found a Lagos-bound bus and waited for it to fill up. It would not depart until all its seats were taken. Chike paid for three spaces and climbed into the front seat. His knees touched the dashboard riddled with stickers preaching platitudes. GOD’S TIME IS BEST. NO FOOD FOR LAZY MAN. A silver Christ dangled crucified from the rearview mirror.

He and his mother had always sat in the front seats when she accompanied him to his military school in Zaria.

All through the journey from Ibadan to Zaria, his mother would hold his hand and he would look out the window, Ogbomoso, to Jebba, to Kutiwenji, to Machuchi, breathing in the changing air, and the landscape changing, and the people changing, growing leaner and more dignified, calmer and more reposed. It was years later, reading the memoirs of a colonial officer, that he realized he had seen the north like a white man, looking for differences: thinner noses, taller grass, different God.

“Don’t sit at the back,” he said when he glanced in the rearview mirror and saw again that Isoken was as far from him and Yẹmi as possible. In his last year in Zaria, on his way home for the holidays, there had been an accident. A bus hit them from behind and the whole back row died instantly, spines snapped. He had bled from a few surface wounds but he had made the trip back to Zaria when the holiday was over. He would be an officer and a gentleman before he let the vagaries of an expressway stop him. And now he was an officer and a deserter.

Even at sixteen, he had known it was partly rubbish, the dross of an empire, the dregs of a martial philosophy that had led countless Africans to fight for “King and Country.” But there had been something seductive about it, something about these military principles, stated like the first principles that governed the world: honor, chivalry, duty.

Evening was falling. The bus was filling. A couple boarded, the man’s frayed Bible held to his chest, the woman in a skirt that covered her ankles, her earlobes smooth and unpierced, her neck and wrists bare of jewelry. A man was moving from bus to bus, peering inside and then darting to the next one. He disappeared into one of the luxurious buses, behemoth American imports as large as whales. A moment later, like Jonah spat out, the man came rushing down.

Their trail had been picked up from the guns abandoned in the bush, their movements traced to this motor park. Were they so important? Would the colonel expend so much energy to find him and Yẹmi? The man was only a few buses away. Chike recognized the brown singlet he had spent the morning walking behind.

“Brother Chike!”

When had Fineboy picked up his name? He was knocking on the side of the bus now.

“You know him?” the driver asked.

“Brother Chike, please, I need to talk to you.”

Brother. Such respect. The boy had put his hand through the window, stopping just short of touching his arm.

“I know him,” he said, opening the bus door.

“Na why you dey answer this boy?”

“Don’t let anyone take my seat,” Chike said to Yẹmi.

Chike climbed down and faced him.

“Yes. What do you want?”

“Please can we move away?”

There was the carcass of a trailer truck stripped to its frame, resting on its side and waiting for the resurrection to rise again. A rubbish heap grew like a shrub beside it, emptying the area of passersby. Fineboy led him there.

“I need to get out of Yenagoa tonight.”

“Your affairs do not concern me.”

“Please. I take God beg you. Soldier is looking for me. I could not go home. I saw my friend Amos on the way. He said there are people watching my house. I don’t have the money to leave.”

“What about your family?”

“They have my picture. They will kill me. They have already killed one of the boys who came home on my street.”

“I should put you and the girl you tried to rape in the same bus?”

“I wasn’t even there. It was a story they told me when they came back to camp. Nobody raped her. That’s what she said. I got the story wrong. Let thunder strike me if I am lying. Let thunder kill my whole family.”

He touched his index finger to his lip and raised it to the sky.

“You can come with us to Lagos. Stand up. What’s that your name again?”

“Fineboy.”

“Fineboy, stand up. It’s a loan you’ll pay back when you find your feet. Make sure you don’t sit next to her.”

He paid Fineboy’s fare and the boy climbed into the back. The last space in the bus was next to Chike. Whoever sat there would feel the driver’s hand each time he reached down to change gears, his knuckles brushing against legs and knees. Women in particular hated this seat.

“This driver is too greedy,” a passenger said.

“So because of one seat, we will leave Bayelsa so late.”

“Driver, make we dey go o.”

“Look, I can’t take this anymore. Do you know who I am? I’m coming down from this bus.”

“Lagos?” a woman asked, running and out of breath.

“Yes.” She paid and he got down for her to enter. She smelled expensive, like the clear alcohol perfumes his mother sprayed for special events, crushed flowers and party stew, the scent of an occasion. The driver started the bus.

“Wait!” the man carrying the large Bible said.

“Mr. Man, I have an appointment tomorrow morning. Let’s be going.”

“What if you die before then? Can a dead body attend a meeting?”

“God forbid.”

“Then let us pray. Father, in the name of Jesus, we commit this bus journey into your hands. We command that no accident shall befall us.”

“Amen,” the other passengers said.

“We declare that we have not set out on a night when the road is hungry.”

“Amen.”

“I cover each and every one of us with the blood of Jesus.”

“Blood of Jesus,” the passengers intoned.

“I wash the wheels of the bus with the blood of Jesus.”

“Blood of Jesus.”

“I soak the driver’s eyes with the blood of Jesus.”

“Blood of Jesus.”

“He will see clearly and by your grace, tomorrow morning we will arrive safely in Lagos. We thank you, Father.”

“Thank you, Lord.”

“We give you all the glory for in Jesus’ name we have prayed.”

“Amen.”

“And all God’s people said?”

“Amen!”