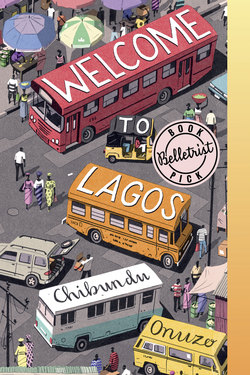

Читать книгу Welcome to Lagos - Chibundu Onuzo - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление14

Between Bayelsa and Lagos

THE HEADLAMPS SHONE ON an empty highway, the driver barely dropping speed as he swerved around potholes. Chike felt safer watching the road. When a bump appeared, he pressed his foot on the bus floor. When they swung around a car wreck, he tilted his head to the left, his reflexes joined to the driver’s. On either side the forest crowded, the arc from the front lights brushing its outermost branches.

All around him was the rhythm of sleep. Gradually, as the driver did not fail and no accident befell them, the road began to lose interest. He brought out his pocket Bible and the emergency flashlight he always carried with him. The book slid open to the Psalms. Our soul is escaped as a bird out of the snare of the fowlers: the snare is broken, and we are escaped. How easy it was to appropriate these words and twist them into something personal. The snare was the army. The fowler was the colonel. And the bus, where did the bus feature in this nest of metaphors?

The men of his platoon would have been interrogated by now. He hoped they had returned to base before reporting him missing. Not just for his sake. They would need a story with details they could all remember. Even if questioned separately, they would not budge. Or so he hoped. It was misplaced concern. He should have stayed to challenge Benatari and add his corpse to the body count in the Delta.

He turned off his torch and put the Bible away. How long till Lagos? It was like London, they said, everything was new and expensive. Big cars, models you would never see anywhere else in Nigeria. Large houses. Money everywhere. And under these fantastic stories of riches, always a layer of unease: of daylight robberies and mysterious disappearances.

The woman beside him no longer breathed evenly. She gave no other sign she was awake. Her arm remained resting on his, where it had fallen in her sleep. She was crying, he realized.

“Excuse me, is everything all right?” Chike asked.

“I thought everyone was asleep.”

“Do you need a light?”

“I’ve found what I’m looking for.”

She blew her nose softly, the mucus sliding out in a rasp. He laid his head on the window again and watched the road. A few moments later, she began to cry again.

“Are you sure there’s nothing I can do for you?”

“I’m tired but this man’s driving won’t let me sleep. And I checked before getting on the bus. He looked responsible. How am I going to manage till Lagos?”

“Will it be your first time in the city?” he asked.

“No, but I can’t wait to arrive. I tire for this Niger Delta. It’s so dangerous these days. Once you step out of your house, you’re afraid. If it’s not kidnapping, it’s armed robbery or assassination.”

“Yes,” Chike said. “It’s becoming something else. I hope you don’t mind my asking, but if I was trying to find somewhere reasonable to stay in Lagos, where would you advise?”

“You can try Ojota or Ketu. That’s around where I’ll be staying. I haven’t even told my cousin I’m arriving tomorrow morning. I called her number but it’s not going through.”

“Do you have an address?” Chike asked.

“Yes, of course. I just hope she won’t turn me away.”

“I’m sure she won’t.”

“Why are you so sure? Nobody knows I’m going to Lagos,” she said, her voice suddenly cracking in a sob. “I’m running away.”

Chike was the one who had drawn her out into conversation and now he wished he had left her to her tears.

“My husband beats me. Often. My mother said I should prepare his favorite soup for him, ofe nsala with plenty stockfish. My brother says I should beg him. They’ve all told me to stay. Stay so the police can discover my dead body.”

She blew her nose, a loud snort rushing into her tissue.

“Softly o. No injure yourself,” the driver said.

“Instead of him to focus on what he’s driving. I’m going to feel very embarrassed tomorrow. I wish I could make you forget everything I’ve said.”

“I can tell you my own secret,” Chike said. “Grown man like me, I’m scared of Lagos.”

“Why? Because there are too many Yorubas?”

“And how do you know I’m not Yoruba?”

“You just have this Igbo look about you. And anyway, what’s a Yoruba man doing in Bayelsa if he’s not in the army?”

How had she guessed, Chike wondered. Was there something about him that spoke of death? Over a decade in the military not so easily disguised by plain clothes?

“As for me,” she continued, “the first time I arrived in Lagos, stepping down at the motor park was a shock. I grew up in the east, so to have everybody crowding around you, speaking this language you don’t understand, I fear o. Somebody can sell you in the market, you won’t know.”

“I speak enough Yoruba, but Lagos just has this reputation.”

“Armed robbers. Ritual killers. Drug dealers. It’s like that and it’s not like that. I always enjoy my visits. There’s something always happening there. Ngwanu, let us sleep. You don’t want to be tired when you get to Lagos. Good night.”

“Thanks. Good night.”

Chike put his temple on the window and continued to watch the road. A year ago, he would never have believed he could leave the army, so set was he in the routine of military life. Yet here he was on his way to Lagos. He was not too old to adopt and adapt new methods. There was a new life waiting for him in Lagos. He would make his way.