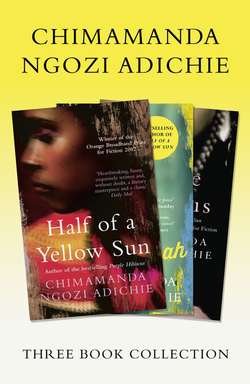

Читать книгу Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah, Purple Hibiscus: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Three-Book Collection - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie - Страница 19

Оглавление9

Richard watched as Kainene zipped up the lilac dress and turned to him. The hotel room was brightly lit, and he looked at her and at her reflection in the mirror behind her.

‘Nke a ka mma,’ he said. It was prettier than the black dress on the bed, the one she had earlier picked out for her parents’ party. She bowed mockingly and sat down to put on her shoes. She looked almost pretty with her smoothing powder and red lipstick and relaxed demeanour, not as knotted up as she had been lately, chasing a contract with Shell-BP. Before they left, Richard brushed aside some of her wig hair and kissed her forehead, to avoid spoiling her lipstick.

There were garish balloons in her parents’ living room. The party was underway. Stewards in black and white walked around with trays and fawning smiles, their heads held inanely high. The champagne sparkled in tall glasses, the chandeliers’ light reflected the glitter of jewellery on fat women’s necks, and the High Life band in the corner played so loudly, so vigorously, that people clumped close together to hear one another.

‘I see many Big Men of the new regime,’ Richard said.

‘Daddy hasn’t wasted any time in ingratiating himself,’ Kainene said in his ear. ‘He ran off until things calmed down, and now he’s back to make new friends.’

Richard scanned the rest of the room. Colonel Madu stood out right away, with his wide shoulders and wide face and wide features and head that was above everyone else’s. He was talking to an Arab man in a tight dinner jacket. Kainene walked over to say hello to them and Richard went to look for a drink, to avoid talking to Madu just yet.

Kainene’s mother came up and kissed his cheek; he knew she was drunk, or she would have greeted him with the usual frosty ‘How do you do?’ Now, though, she told him he looked well and cornered him at an unfortunate end of the room, with the wall to his back and an intimidating piece of sculpture, something that looked like a snarling lion, to his side.

‘Kainene tells me you are going home to London soon?’ she asked. Her ebony complexion looked waxy with too much make-up. There was something nervous about her movements.

‘Yes. I’ll be away for about ten days.’

‘Just ten days?’ She half smiled. Perhaps she had hoped he would be away for longer, so she could finally find a suitable partner for her daughter. ‘To visit your family?’

‘My cousin Martin is getting married,’ Richard said.

‘Oh, I see.’ The rows and rows of gold around her neck weighed her down and made her head look slumped, as if she was under great strain and, in trying so hard to hide it, made it all the more obvious. ‘Maybe we’ll have a drink in London then. I’m telling my husband that we should take another small holiday. Not that anything will happen, but not everybody is happy with this unitary decree the government is talking about. It’s just nicer to be away until things are settled. We may leave next week but we are not telling anybody, so keep it to yourself.’ She touched his sleeve playfully, and Richard saw a glimpse of Kainene in the curve of her lips. ‘We are not even telling our friends the Ajuahs. You know Chief Ajuah, who owns the bottling company? They are Igbo, but they are Western Igbo. I hear they are the ones who deny being Igbo. Who knows what they will say that we have done? Who knows? They will sell other Igbo people for a tarnished penny. A tarnished penny, I’m telling you. Do you want another drink? Wait here and I’ll get another drink. Just wait here.’

As soon as she lurched away, Richard went looking for Kainene. He found her on the balcony with Madu, standing and looking down at the swimming pool. The smell of roasting meat was thick in the air. He watched them for a while. Madu’s head was slightly cocked to the side as Kainene spoke, her body looked frail next to his huge frame, and they seemed somehow to fit effortlessly. Both very dark, one tall and thin, the other taller and huge. Kainene turned and saw him.

‘Richard,’ she said.

He joined them, shook hands with Madu. ‘How are you, Madu? A na-emekwa?’ he asked, eager to speak first. ‘How is life in the North?’

‘Nothing to complain about,’ Madu said in English.

‘You didn’t come with Adaobi?’ He did wish the man would come out more often with his wife.

‘No,’ Madu said, and sipped his drink; it was clear he had not wanted anybody to disturb their chat.

‘I see my mother was entertaining you, how exciting,’ Kainene said. ‘Madu and I were stuck with Ahmed there for a while. He wants to buy Daddy’s warehouse in Ikeja.’

‘Your father will not sell anything to him,’ Madu declared, as if it were his decision to make. ‘Those Syrians and Lebanese already own half of Lagos, and they are all bloody opportunists in this country.’

‘I would sell to him if he stopped smelling so awfully of garlic,’ Kainene said.

Madu laughed.

Kainene slipped her hand into Richard’s. ‘I was just telling Madu that you think another coup is coming.’

‘There won’t be another coup,’ Madu said.

‘You would know, wouldn’t you, Madu? Big Man colonel that you are now,’ Kainene teased.

Richard tightened his hold on her hand. ‘I went to Zaria last week, and it seemed that all everybody was saying was second coup, second coup. Even Radio Kaduna and the New Nigerian,’ he said in Igbo.

‘What does the press know, really?’ Madu replied in English. He always did that; since Richard’s Igbo had become near-fluent, Madu insistently responded to it in English so that Richard felt forced to revert to English.

‘The papers ran articles about jihad, and Radio Kaduna kept broadcasting the late Sardauna’s speeches, and there was talk about how Igbo people were going to take over the civil service and – ’

Madu cut him short. ‘There won’t be a second coup. There’s a little tension in the army, but there always is a little tension in the army. Did you have the goat meat? Isn’t it wonderful?’

‘Yes,’ Richard agreed, almost automatically, and then wished he hadn’t. The air in Lagos was humid; standing next to Madu, it seemed suffocating. The man made him feel inconsequential.

The second coup happened a week later, and Richard’s first reaction was to gloat. He was rereading Martin’s letter in the orchard, sitting on the spot where Kainene often told him that a groove the exact size and shape of his buttocks had appeared.

Is ‘going native’ still used? I always knew you would! Mother tells me you have given up on the tribal art book and are pleased with this one, a sort of fictionalized travelogue? And on European Evils in Africa! I’m quite keen to hear more about it when you are in London. Pity you gave up the old title: ‘The Basket of Hands’. Were hands chopped off in Africa as well? I’d imagined it was only in India. I’m intrigued!

Richard imagined that smile Martin often had when they were schoolboys, during those years that Aunt Elizabeth had immersed them in activities with her manic determination that there be no sitting around: cricket tournaments, boxing lessons, tennis, piano lessons from a Frenchman with a lisp. Martin had thrived at them all, always with that superior smile of people who were born to belong and excel.

Richard reached out to pluck a wildflower that looked like a poppy. He wondered what Martin’s wedding would be like; Martin’s fiancée was a fashion designer, of all things. If only Kainene could go with him; if only she didn’t have to stay to sign the new contract. He wanted Aunt Elizabeth and Martin and Virginia to see her, but most of all he wanted them to see him, the man he had become after his years here: to see that he was browner and happier.

Ikejide came up to him. ‘Mr Richard, sah! Madam say make you come. There is another coup,’ Ikejide said. He looked excited.

Richard hurried indoors. He was right; Madu was wrong. The moist July heat had plastered his hair limply to his head, and he ran his hand through it as he went. Kainene was on a sofa in the living room, her arms wrapped around herself, rocking back and forth. The British voice on the radio was so loud that she raised her voice when she said, ‘Northern officers have taken over. The BBC says they are killing Igbo officers in Kaduna. Nigerian Radio isn’t saying anything.’ She spoke too fast. He stood behind her and began to rub her shoulders, kneading her stiff muscles in circular motions. On the radio, the breathless British voice said it was quite extraordinary that a second coup had occurred only six months after the first.

‘Extraordinary. Extraordinary indeed,’ Kainene said. She reached out, in a sudden jerky move, and pushed the radio off the table. It fell on the carpeted floor, and a dislodged battery rolled out. ‘Madu is in Kaduna,’ she said, and put her face in her hands. ‘Madu is in Kaduna.’

‘It’s all right, my darling,’ Richard said. ‘It’s all right.’

For the first time, he considered the possibility of Madu’s death. He decided not to go back to Nsukka for a while and was not sure why. Was it really because he wanted to be with her when she heard Madu was dead? In the next few days, she was so taut with anxiety that he too began to worry about Madu and then resent himself for doing so, and then resent his resentment. He should not be so petty. She included him in her worry, after all, as if Madu was their friend and not just hers. She told him about the people she called, about the inquiries she made to find out what had happened. Nobody knew. Madu’s wife had heard nothing. Lagos was in chaos. Her parents had left for England. Many Igbo officers were dead. The killings were organized; she told him about a soldier who said the alarm for a battalion muster parade was sounded in his barracks and after everyone assembled, the Northerners picked out all the Igbo soldiers and took them away and shot them.

Kainene was muted and quiet but never tearful, so the day she told him, ‘I heard something,’ with a sob in her voice, he was sure it was news of Madu. He thought about how to console her, whether he would be able to console her.

‘Udodi,’ Kainene said. ‘They killed Colonel Udodi Ekechi.’

‘Udodi?’ He had been so certain it was about Madu that for a moment he was blank.

‘Northern soldiers put him in a cell in the barracks and fed him his own shit. He ate his own shit.’ Kainene paused. ‘Then they beat him senseless and tied him to an iron cross and threw him back in his cell. He died tied to an iron cross. He died on a cross.’

Richard sat down slowly. His dislike for Udodi – loud, drunken, duplicity dripping from his pores – had only deepened in the past years. Yet hearing about his death left him sober. He thought, again, of Madu dying and realized he did not know how he would feel.

‘Who told you this?’

‘Maria Obele. Udodi’s wife is her cousin. She said they are saying that no Igbo officer in the North escaped. But some Umunnachi people said they heard Madu escaped. Adaobi has not heard anything. How could he have escaped. How?’

‘He might be hiding out somewhere.’

‘How?’ Kainene asked again.

Colonel Madu appeared in Kainene’s house two weeks later, much taller-looking now because he had lost so much weight; the angles of his shoulder bones were visible through his white shirt.

Kainene screamed. ‘Madu! Is this you? O gi di ife a?’

Richard was not sure who walked towards whom first, but Kainene and Madu were holding each other close, Kainene touching his arms and face with a tenderness that made Richard look away. He went to the liquor cabinet and poured a whisky for Madu and a gin for himself.

‘Thank you, Richard,’ Madu said, but he did not take the drink and Richard stood there, holding two glasses, before he placed one down.

Kainene sat on a side table in front of Madu. ‘They said they shot you in Kaduna, then they said they buried you alive in the bush, then they said you escaped, then they said you were in prison in Lagos.’

Madu said nothing. Kainene stared at him. Richard finished his drink and poured another.

‘You remember my friend Ibrahim? From Sandhurst?’ Madu asked finally.

Kainene nodded.

‘Ibrahim saved my life. He told me about the coup that morning. He was not directly involved, but most of them – the Northern officers – knew about it. He drove me to his cousin’s house, but I didn’t really understand until he asked his cousin to take me to the backyard, where he kept his domestic animals. I slept in the chicken house for two days.’

‘No! Ekwuzina!’

‘And do you know that soldiers came to search his cousin’s house to look for me? Everybody knew how close Ibrahim and I were, and they suspected he helped me escape. They didn’t check the chicken house, though.’ Colonel Madu paused, nodding and looking into the distance. ‘I did not know how bad chicken shit smelt until I slept in it for three days. On the third day, Ibrahim sent me some kaftans and money through a small boy and asked me to leave right away. I dressed as a Fulani nomad and walked through the smaller villages because Ibrahim said that artillery soldiers had set up blocks on all the major roads in Kaduna. I was lucky to find a lorry driver, an Igbo man from Ohafia, who took me to Kafanchan. My cousin lives there. You know Onunkwo, don’t you?’ Madu did not wait for Kainene to respond. ‘He is the station master at the railway, and he told me that Northern soldiers had sealed off Makurdi Bridge. That bridge is a grave. They searched every single vehicle, they delayed passenger trains for up to eight hours, and they shot all the Igbo soldiers they discovered there and threw the bodies over. Many of the soldiers wore disguises, but they used their boots to find them.’

‘What?’ Kainene leaned forwards.

‘Boots.’ Madu glanced at his shoes. ‘You know we soldiers wear boots all the time so they examined the feet of each man, and any Igbo man whose feet were clean and uncracked by harmattan, they took away and shot. They also examined their foreheads for signs of their skin being lighter from wearing a soldier’s beret.’ Madu shook his head. ‘Onunkwo advised me to wait for some days. He did not think I would make it across the bridge because they would recognize me easily under any disguise. So I stayed ten days in a village near Kafanchan. Onunkwo found me different houses to stay in. It was not safe to stay with him. Finally, he said he had found a driver, a good man from Nnewi, who would hide me in the water tank of his goods train. The man gave me a fireman’s suit to wear and I climbed into the tank. I had water up to my chin. Each time the train jerked, some of the water entered my nose. When we got to the bridge, the soldiers searched the train thoroughly. I heard footsteps on the lid of the tank and thought it was all over. But they did not open it and we passed. It was only then I knew that I was alive and I would survive. I came back to Umunnachi to find Adaobi wearing black.’

Kainene kept looking at Madu long after he finished speaking. There was another stretch of silence, which made Richard uncomfortable because he was not sure how to react, what expression to have.

‘Igbo soldiers and Northern soldiers can never live in the same barracks after this. It is impossible, impossible,’ Colonel Madu said. He had a glassy sheen in his eyes. ‘And Gowon cannot be head of state. They cannot impose Gowon on us as head of state. It is not how things are done. There are others who are senior to him.’

‘What are you going to do now?’ Kainene asked.

Madu did not seem to hear her. ‘So many of us are gone,’ he said. ‘So many solid, good men – Udodi, Iloputaife, Okunweze, Okafor – and these were men who believed in Nigeria and didn’t care for tribe. After all, Udodi spoke better Hausa than he spoke Igbo, and look how they slaughtered him.’ He stood up and began to pace the room. ‘The problem was the ethnic balance policy. I was part of the commission that told our GOC that we should scrap it, that it was polarizing the army, that they should stop promoting Northerners who were not qualified. But our GOC said no, our British GOC.’ Madu turned and glanced at Richard.

‘I’ll ask Ikejide to cook your special rice,’ Kainene said.

Madu shrugged, silent, and stared out of the window.